PARTE I. DIO O L'UMANITÀ SEZIONE B · 172 a. joos (edizione 2011) (r-vp1sb1) teologie oggi,...

Transcript of PARTE I. DIO O L'UMANITÀ SEZIONE B · 172 a. joos (edizione 2011) (r-vp1sb1) teologie oggi,...

172

A. JOOS (edizione 2011) (R-VP1SB1) TEOLOGIE OGGI, PANORAMICA DELLE CORRENTI A DIALOGO. CHIAVE DI LETTURA DEI

CONFRONTI E CONVERGENZE NEL XX-XXI SECOLO

VOLUME I. TRA RISCOPERTA CRISTIANA E VERIFICA DELLA CREDIBILITÀ TEOLOGICA OGGI

PARTE I. DIO O L'UMANITÀ

SEZIONE B

VERIFICARE LA FEDE OGGI. IL RADICALE RIFERIMENTO

ALL’EMANCIPAZIONE UMANA E LA “MORTE DI DIO”

VERIFYING FAITH TODAY – THE RADICAL REFERENCE TO HUMAN EMANCIPATION IN MODERNITY

AND THE “DEATH OF GOD”

INTRODUZIONE: LA RAPIDA FIAMMATA DELLA TEOLOGIA RADICALE O ‘TEOLOGIA DELLA MORTE DI

DIO’ NEL XX SECOLO

◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈◈

Occorre ovviamente chiarire un attimo ciò che significa nella nostra indagine –dalla

documentazione e dal percorso teologico studiato- l’espressione ‘teologia radicale’ di fronte alla

dicitura che sembra volersi proporre all’inizio del XXI secolo in proposito 1. Questa applicazione

posteriore della ‘radicalità’ estende –da una prospettiva più secolare ed anzi ‘militare’- a contesti

di radicalità religiose legate al terrorismo di gruppi fondamentalisti di tipo islamista con intenti

politici radicali. Nella nostra prospettiva ci muoviamo lungo l’itinerario della teologia cristiana che

prende forma nel corso del XX secolo e che è stata chiamata la corrente ‘radicale’, o ‘process

theology’ o ‘teologia della morte di Dio’. Esiste anche l’intento ebraico che situa una ‘teologia

radicale’ come ambientazione teologica dopo l’esperienza distruttiva dell’Olocausto (Kaplan e

1 W. D. Brinkley - R. Yarger, (USAWC STRATEGY RESEARCH PROJECT), RADICAL THEOLOGY AS A DESTABILIZING ASPECT OF THE 21ST

CENTURY STRATEGIC SECURITY CONTINUUM, in «Internet» 2011, http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-

bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA448500.

173

Rubenstein) 1. Con il riferimento biblico più diretto, certi legami impliciti con la teologia radicale

cristiana del XX secolo possono essere evidenziati.

Torniamo perciò alla nostra chiave di lettura complessiva che risultava dalla raccolta

articolata e possibilmente organica delle varie correnti teologiche ed orientamenti del XX-XXI

secolo 2. La prima risposta di verifica teologica alla riscoperta del mistero di Dio in chiave

1 R. S. Halachmi, Radical Theology: Confronting the Crises of Modernity. The findings of modern science and the tragedy of the Holocaust led

some Jewish thinkers to redefine God, in «Internet» 2011, http://www.myjewishlearning.com/beliefs/Theology/

God/Modern_Views/Radical_Theology.shtml: «The Death of God. Kaplan's major works predate the Holocaust, but for other modern Jewish

thinkers the Holocaust is the starting point for radical theology. Richard Rubenstein--also an ordained Conservative rabbi--also argues that

one cannot sustain a belief in a supernatural God, not because of the truths of modernity, but because of the events of the Nazi era.

Rubenstein recognized that traditional Judaism asserts that Jewish suffering is the result of Jewish sin. Thus the Holocaust should be

explained as an event initiated by God in order to punish the Jews. Rubenstein, however, could not believe in such a God. In his After

Auschwitz (1966), Rubenstein wrote: "To see any purpose in the death camps, the traditional believer is forced to regard the most demonic,

anti-human explosion of all history as a meaningful expression of God's purposes. The idea is simply too obscene for me to accept." The

reality of Auschwitz created a void where once the Jewish people had experienced God's presence. There is no aspect of post-Holocaust life

that is untouched by that reality, neither for the victims nor for those who lived in safety. However this shift in the experience of the world is

something that most prefer not to articulate. Even though most Jews continue to go to synagogue for a variety of reasons, "once inside, we

are struck dumb by words we can no longer honestly utter. All that we can offer is our reverent and attentive silence before the Divine." His

position, he argues, is not that of the atheist, but rather that of one who lives after the Holocaust, in a world where we know of the death of

God. The "thread uniting God and man, Heaven and earth, has been broken." Our current reality is one without any superhuman power,

without any Divine pathos, and one in which we have nothing to say about God. Eventually, however, Rubenstein developed a conception of

God that he felt more comfortable with. In place of the traditional conceptions of God, Rubenstein suggested that we turn to a concept of

God as Holy Nothingness. This God--not far off from certain mystical conceptions of God--is entirely without definition, yet is the source of

all creation. This God can be found in nature. In fact, God is the order found in nature, which no power can transcend».

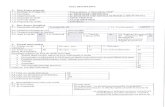

TEOLOGIA DEL XX SECOLO

◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎◎

LA RISCOPERTA CRISTIANA LA VERIFICA CRISTIANA

L’ORIGINALITÀ CRISTIANA █ LA SCOMMESSA CRISTIANA

QUALE DIO?------------------------------------------QUALE UMANITÀ?

Teologia della Parola Teologia della morte di Dio

(K. Barth) (teologi radicali)

Antropologia trascendentale

(K. Rahner)

QUALE RELAZIONALITÀ TRA DIO E UMANITÀ?

QUALE CRISTO?-------------------------------------------------QUALE UNIVERSO?

Teologia esistenziale Teologia della pan-cristificazione

(R. Bultmann) (P. Teilhard de Chardin)

Cristologia storico-realista

(O. Cullmann)

QUALE MEDIAZIONE TRA CRISTO E L’UNIVERSO?

QUALE CHIESA?-------------------------------------------------QUALE SOCIETÀ?

Ecclesiologia di conciliarità Teologia della secolarizzazione

(S. Bulgakov) (D. Bonhoeffer)

Ecclesiologia ecumenica

(Y. Congar...)

QUALE COMPRESENZA TRA CHIESA E COMUNITÀ SOCIALE?

QUALE PERCORSO ORIGINARIO QUALE ESITO FINALE

NEL PRIMO SEGNO ESPRESSIVO?----------------------------------NELL’ULTIMO COMPIMENTO?

Ecclesiologia eucaristica Teologia della speranza

(N. Afanas’ev) (Moltmann)

Teologia della storia

(W. Pannenberg)

QUALE PROGETTO DELLA CHIESA NELLA STORIA?

QUALE PRESENZA VISSUTA - QUALE COMPLEMENTARIETÀ

NELL’IMPEGNO CONCRETISSIMO?---------------------------------NELLA PENETRAZIONE CULTURALE?

Teologia della liberazione Teologia neo-culturale

174

barthiana si afferma come “teologia radicale” o “teologia della morte di Dio”, nella quale si vuole

prendere pienamente in conto le implicazioni dell’emancipazione umana dalla ‘modernità’. In

modo del tutto generico ci si chiederà quale possa essere la rilevanza della riscoperta prospettata

dalla teologia dialettica di fronte all’emancipazione umana nella sua consapevolezza di essere

ormai ‘adulta’ nei tempi moderni (ma non ancora ‘postmoderni’). Se la personalità di Karl Barth

domina, incontestata, tutto l'orizzonte dell'affermazione solenne di Dio nel secolo XX, ci troviamo

adesso davanti a un altro stile e a un diverso contesto teologico. Esso riguarda il riferimento

prioritario all'intento umano. Esso ha avuto una sua fiammata, con impatto più immediato, ma

anche con una più rapida retrocessione di notorietà dopo gli anni sessanta. Diversi dei suoi

esponenti si orienteranno verso ambiti ulteriori di riflessione. La sponda dell'affermazione decisa

di Dio ci aveva portato a considerare brevemente il tentativo barthiano e le prospettive che esso

apre. Il nostro confronto prosegue ora con l'esame di una posizione assai contrapposta alla

teologia della Parola. Anch'essa potrebbe essere chiamata sponda ricapitolativa di verifica nella

teologia del XX secolo. Essa si presenta come trasversale nel paesaggio del confessionalismo

cristiano (fino all’intento ebraico) 1. La fiammata radicale della metà del XX secolo viene fatta

risalire però talvolta anche al XIX secolo che ne ha caratterizzato i primi avvisagli, spiegandone il

perché nel quando 2. Queste radici sono così determinanti per la comprensione della verifica

(teologi della liberazione) (P. Tillich)

Teologia della divino-umanità

(P. Florenskij)

QUALE COMPENETRAZIONE TRA CHIESA ED ESPERIENZA UMANA? VALENZE ANTROPOLOGICHE DELLA CHIAVE DI LETTURA

1 T. - W. Brock, Radical Theology and the Death of God by Thomas Altizer and William Hamilton, in «Internet» 2011, «Religion online»,

http://www.religion-online.org/showchapter.asp?title=537&C=584: «Radical theology is a contemporary development within Protestantism

-- with some Jewish, Roman Catholic and non-religious response and participation already forming -- which is carrying the careful

openness of the older theologies toward atheism a step further. It is, in effect, an attempt to set an atheist point of view within the spectrum

of Christian possibilities. While radical theology in this sense has not yet become a self-conscious "movement," it nevertheless has gained

the interest and in part the commitment of a large number of Christians in America, particularly from students of all disciplines, and from

the younger ranks of teachers and pastors. The aim of the new theology is not simply to seek relevance or contemporaneity for its own sake

but to strive for a whole new way of theological understanding. Thus it is a theological venture in the strict sense, but it is no less a pastoral

response hoping to give support to those who have chosen to live as Christian atheists. The phrase "death of God’’ has quite properly

become a watchword, a stumbling-block, and something of a test in radical theology, which itself is a theological expression of a

contemporary Christian affirmation of the death of God. Radical theology thus best interprets itself when it begins to say what it means by

that phrase. The task of clarifying the possible meanings of the phrase, "death of God," is scarcely begun in the essays of this volume, but no

student of Nietzsche will be surprised at this inconclusiveness, recalling the widely different interpretations Nietzsche’s proclamation of the

death of God has received in the twentieth century. Nor should the phrase "death of God" be linked to Nietzsche alone, for in one way or

another it lies at the foundation of a distinctly modern thought and experience. Perhaps the category of "event’’ will prove to be the most

useful answer to the recurring question, "Just what does ‘death of God’ refer to?" But not even this specification sufficient ly narrows the

meaning to make definition possible, and if one wanted to, one could list a range of possible meanings of the phrase along such lines as

these, moving slowly from conventional atheism to theological orthodoxy».

2 T. - W. Brock, Radical Theology and the Death of God by Thomas Altizer and William Hamilton. Preface, in «Internet» 2005, http://www.

religiononline.org/showbook.asp?title=537: «If the death of God is an event of some kind, when did it happen and why? In response to this

sort of self-query, radical theology is being more and more drawn into the disciplines of intellectual history and literary criticism to answer

the "when" question, and into philosophy and the behavioral sciences to answer the "why" question. One of the major research tasks now

facing the radical theologians is a thorough-going systematic interpretation of the meaning of the death of God in nineteenth-century

European and American thought and literature, from, say, the French Revolution to Freud. This means finding a common principle of

interpretation to handle such divergent strands as the new history and its consequent historicism, romantic poetry from Blake to Goethe,

Darwin and evolutionism, Hegel and the Hegelian left, Marx and Marxism, psychoanalysis, the many varieties of more recent literature

including such divergent figures as Dostoevsky, Strindberg and Baudelaire, and, of course, Nietzsche himself. Of course the questions "why

did it happen" and "when did it happen," cannot fully be answered in nineteenth century terms. Nevertheless, it is increasingly true that the

nineteenth century is to radical theology what the sixteenth century was to Protestant neo-orthodoxy. For only in the nineteenth century do

we find the death of God lying at the very center of vision and experience. True, we can learn a great deal about the death of God in the

history of religions, if only because gods have always been in the process of dying, from the time the sky gods fell into animism to the

disappearance of a personal or individual deity in the highest expression of mysticism. Yet, it is in Christianity and Christianity alone that we

find a radical or consistent doctrine of the Incarnation. Only the Christian can celebrate an Incarnation in which God has actually become

flesh, and radical theology must finally understand the Incarnation itself as effecting the death of God. Although the death of God may not

175

radicale? O essa fa parte della specificità avviata dalla nascita stessa della teologia del XX secolo in

quanto tale? Risalendo indietro, la priorità data alla persona umana sorge dalla stessa

emancipazione dell’intento umano dai poteri di diritto divino, con particolare riferimento alla

modernità e alla Rivoluzione francese. L’emancipazione, diranno alcuni commentatori, è il

passaggio di un 'vecchio ordine cristiano' verso un 'nuovo ordine' 1. La modernità ed i tempi

moderni iniziano verso il XVI secolo con un insieme di caratteristiche riguardo alle modifiche

storiche in seno alla convivenza umana (l’umanesimo, la Riforma, le scoperte scientifiche,

l’illuminismo nascente, le rivoluzioni sociopolitiche, la produttività industriale) 2. Vi sarebbe

particolarmente una modifica della visione 'storica' e di approccio alla natura stessa 3. Il discorso si

amplia allora notevolmente. Più direttamente riguardo al XX secolo, diversi sono i nomi che si sono

imposti all'attenzione negli anni 60, formando un gruppo che ha portato avanti questa

problematica per alcuni anni, prima di svanire dall'interesse del pubblico o delle cronache. Un

primo teologo da menzionare è il vescovo di Woolwich della comunione anglicana, John A. T.

Robinson, il quale aderisce all'orientamento radicale partendo dalla sua esperienza pastorale 4.

have been historically actualized or realized until the nineteenth century, the radical theologian cannot dissociate this event from Jesus and

his original proclamation».

1 B. Lambert, "Gaudium et spes" and the Travail of Today's ecclesial Conception, in J. Gremillion, The Church and Culture since Vatican II,

Indiana (USA) 1985, pp. 35-36: «Granted that the Church can neither follow nor remake the Christian order of former times, it must then

construct another one. The force of the evidence compels that conclusion. But what course should the Church take? In whatever direction the

Church looks, the secularization of the image of the world presents itself. If one excepts Islam, where the Koran considers the sacred and the

profane as one whole, the contemporary world embraces the image of a secularized world. Sacral forms of society have been torn down. The

culture of Western origin, which has penetrated the land mass of the globe, desires to be autonomous, profane, laic. What is secularization?

It is the process by which a society strips itself of the religious ideas, beliefs, and institutions that once governed its l ife in order to make

itself autonomous; that is, to find within itself and solely by reference to itself, the methods, structures, and laws of societal living. I shall not

attempt to deal with the distant antecedents of its long evolution. That would require going over the history of Western civilization since the

Middle Ages, when the laic spirit appeared. It proceeded through many stages to the liberation of the profane order from religion».

2 L. De Chirico, L’evangelismo tra crisi della modernità e sfida della postmodernità, in «Studi di teologia», 1997 nº 1 (Modernità e

postmodernità), pp. 6-7: «Come si è visto, la modernità è strettamente legata all'età moderna. Dal punto di vista metodologico, non è tanto

importante la determinazione di una data precisa che sancisca le sue origini o la fissazione di una periodizzazione storica; ciò che più

interessa in questa sede è il tentativo di identificare il processo di fori-nazione delle strutture portanti della cultura moderna. Pertanto, nei

parametri storici della modernità possono rientrare quei fenomeni storici, tendenze sociali e movimenti di pensiero che ne hanno contribuito

il sorgere e l'imporsi. In primo luogo, l'Umanesimo del XV secolo promuove la presa di coscienza di una missione tipicamente umana che si

esprime attraverso le humanae litterae; il Rinascimento del XVI secolo conosce una renovatio dello spirito dell'uomo. La scoperta delle opere

degli uomini antichi conduce alla scoperta dell'uomo stesso. La Riforma protestante del XVI secolo è un altro movimento di estrema

importanza. La crisi religiosa del Cinquecento segna la fine dell'unità del mondo cattolico e la messa in discussione dell'autorità e della

gerarchia ecclesiastica; dalla Riforma in poi, la problematizzazione dell'autorità tradizionale e la sua ridefinizione accompagna il definirsi

della modernità. Un apporto decisivo è dato anche dalla rivoluzione scientifica dei secoli XVI e XVII. Dalla pubblicazione del De

Revolutionibus di Copernico nel 1543 al Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica di Newton del 1687 si assiste ad un vero e proprio

stravolgimento della scienza astronomica e della visione del mondo in generale. La scienza diventa l'unico sapere oggettivo e l'avvento della

tecnica trasforma il modo di vita consolidatosi nel secoli precedenti. L'Illuminismo del XVIII secolo può considerarsi la realizzazione

intellettuale della modernità, perlomeno sul piano del consolidamento di vari fermenti di pensiero e sul loro mutamento in progetto

ideologico. La ragione illuminata assurge a criterio assoluto di verità, bellezza, bontà e ordine. Sempre nel XVIII secolo, anche l'epoca

dell'elaborazione politica repubblicana e delle rivoluzioni negli Stati Uniti e in Francia è un importante tassello nel mosaico della modernità.

L'individuo si fa soggetto politico a pieno titolo all'interno di un contesto politico contrassegnato da libertà, fratellanza e uguaglianza. Oltre

alla dimensione intellettuale e politica, la modernità possiede anche una sua connotazione di carattere socio-economico. Lo sviluppo del

modo di produzione capitalistico, la rivoluzione scientifico-tecnologica e l'industrializzazione, la velocizzazione delle comunicazioni,

l'urbanizzazione e la globalizzazione sono tutti fenomeni che determinano la modernizzazione delle strutture sociali dell'occidente e, con

essa, il delinearsi della modernità». 3 WORLD COUNCIL OF CHURCHES, New Directions in Faith and Order (Reports, Minutes, Documents) Bristol 1967 , in «Faith and Order Paper

n° 50», Geneva 1968, p. 9: «Without any deliberate choice on his part, modern man has entered into a new experience and understanding of

nature and history. For many centuries there was a general tendency to consider non-human nature as an entirely earthbound static reality,

this planet being conceived as the stage for the drama of human life. In European culture, history was thought of as covering a short period

of but a few thousand years, and also as a basically static reality, within which Fall, Incarnation and Consummation were seen as three

incidents, of which the second and the third aimed at the restoration of a supposedly perfect beginning».

4 J. A. T. Robinson, nato nel 1919, studia a Marlborough, si specializza in scienze bibliche a Cambridge, cura pastorale a Bristol, è vescovo

episcopaliano di Woolwich nel 1951; nel 1959, decano del Clare College, Cambridge.

176

Accanto a lui si può citare tra gli altri Gabriel Vahanian 1, calvinista francese e formato lui pure

negli Stati Uniti, e da cui prese nome il movimento di riflessione sulla ‘morte di Dio’. Altri

esponenti fanno parte del gruppo che lanciò la riflessione radicale sulla morte di Dio: Paul Van

Buren 2, William Hamilton 3, Thomas Altizer 4, sono tra i più rappresentativi. Altri autori si

aggiungono all’ambito radicale, come Don Cupitt ed il suo “religious non realism” 5. John B. Cobb 6

si fa l’avvocato della ricerca di una nuova teologia naturale ispirandosi a Whitehead (contrastando

le inclinazioni antimetafisiche di certi accenni o premesse della ‘morte di Dio’) 7. Altri ancora,

come per esempio Harvey Cox, pure accettando l'appellativo di radicale, si distaccano poi dal

riferimento esclusivo alla morte di Dio 8. Si situano piuttosto al livello del confronto tra Chiesa e

comunità umana e sviluppano una problematica di secolarizzazione e poi di impegno politico, con

particolare riferimento ai problemi sociali del mondo tecnico-scientifico attuale (vedere parte III,

sezione B, «la teologia della secolarizzazione»). Altri ancora, come D. Tracy, si situeranno dentro

al riformismo radicale ma con intento revisionista riguardo alla impostazione teologica cristiana

(più congenialmente legati all’intento della antropologia trascendentale, cfr infra volume II, parte I)

Opere: nel 1960: Liturgy coming to life; 1962: Jesus and his coming, the Emergence of a Doctrine; 1963: pubblica il libro Honest to God;

1965: The New Reformation; 1966: Christian Morals today; 1967: esce il libro Exploration into God e But that, I can't Believe. Altre

pubblicazioni: diversi studi esegetici In the end God - On becoming the Church in the world. - Sposato: 4 figli.

1 Gabriel Vahanian, nato a Marsiglia nel 1927, di confessione calvinista, studia a Grenoble (Francia), poi alla Sorbonne (Parigi), continua gli

studi a Princeton e a Syracuse (USA), comincia la sua riflessione sotto l'influenza di K. Barth. Nel 1961 presenta il libro The Death of God; nel

1964, pubblicazione dell' opera Wait without idols; nel 1966, No other God.

2 Paul Van Buren, dottorato a Basilea con K. Barth, ministro episcopaliano, formazione intellettuale orientata verso la linguistica. Nel 1965,

The Secular Meaning of the Gospel; nel 1969, Theological Explorations.

3 William Hamilton, nato nel 1924, di confessione battista, professore alla Colgate Rochester Divinity School . Nel 1961, The New Essence of

Christianity; nel 1964, Thursday's Child; nel 1966, Radical Theology and the Death of God (Altizer). Sposato: 4 figli.

4 Thomas Altizer, nato nel 1927, laico episcopaliano, studiò alla Università di Chicago, formazione intellettuale influenzata da Mircea Eliade,

orientamento di antropologia e storia delle religioni, visione teologica ispirata tra l'altro a Kierkegaard, professore all'Università di Stato di

New York. Nel 1963, Mircea Eliade and the Dialectics of the Sacred; nel 1964, Theology and the Death of God. Altre pubblicazioni: The

Descent into the Hell; The New Apocalypse; The Gospel of Christian Atheism (1969).

5 THEOLOGY, Radical Theology, in «Internet» 2005, www.faithnet.org.uk: «Don Cupitt was ordained to the Diocese of Manchester in 1959

and until recently was Dean of Emmanuel College, Cambridge (and was Lecturer in the Philosophy of Religion in the University of Cambridge).

Despite being known more for his radical theological pronouncements (the book 'Taking Leave of God' (1980) being one of the more well-

known), he began his spiritual journey as an orthodox Christian (most notably a theist) seeking only, 'to move from grossly inadequate to

less inadequate images of God' (Thisleton p.87). Despite dabbling in the realm of Christology ('Christ and the Hiddenness of God' (1971) and

a contribution in 'The Myth of God Incarnate' (1977 edited by John Hick) this has remained a central theme in his writings. However, to be

committed to defending orthodox Christian theological pronouncements on the nature and being of God (theism) is now far from his

intentions. This is because Cupitt's theology has undergone a radical transformation spanning his literary career up to the present day. In

fact, much of this has taken place in the public domain through his books. As a consequence one must be very specific when speaking of the

'theology of Don Cupitt' and clarify which manifestation of Cupitt's theology one is referring to».

6 Teologo metodista, John B. Cobb, Jr., della Southern California School of Theology at Claremont, California.

7 Cfr J. Cobb - R. Griffin, Process Theology, An Introductory Exposition, Westminster 1977; F. T. Trotter, Variations on the 'Death of God',

Theme in Recent Theology, in B. Murchland, The Meaning of the Death of God, New York 1967, p. 22: «Thus Cobb, in distinction from the

other thinkers referred to, is seriously in search of a new "Christian natural theology" on Whiteheadian presuppositions. Speaking for himself

and a whole generation of younger theologians, Cobb urges serious attention to theological problems: "In our day we must run fast if we

would stand still, and faster still if we would catch up. We can only hope that we will be granted both time and courage 1».

((1) John B. Cobb, Jr., Living Options in Protestant Theology, op. cit., p. 323.)

8 H. Cox, The Seduction of the Spirit, New York 1973, p. 169: «Although I dislike labels, I suppose it is accurate to describe me as a 'radical'

theologian, though I would want to reserve the right to define the term myself. As for the idea of the 'death of God', I do not think it is a

particularly radical one. Above all I do not think 'radical' and 'death of God' should be equated. What then does it mean to me to consider

myself a radical theologian? The answer has a lot to do with what I have been calling 'people's religion'».

177

1, con una critica articolata alla “process theology” pur seguendo una sua process Metaphysics 2.

Le radici di questo orientamento sorgono dall’Europa britannica verso l’America e si conforma

come “process philosophy” con ispiratori tra cui William James, John Dewey e Charles Saunders

Peirce 3. Appartiene anche all’orientamento della verifica complessiva di questo primo livello di

esplorazione teologica del XX secolo la theology of meaningfulness con S. Ogden, che non si

considera completamente estraneo all’indirizzo liberale 4. Egli si situa nell’ambito della process

theology 5, partecipando alla revisione delle formulazioni teologiche più che accantonare l insieme

1 David Tracy, cattolico di comunione romana, nato il 6-1-1939 a New York, ordinato per la diocesi di Bridgeport Connecticut. Difende la sua

tesi dottorale su B. Lonergan; alcune opere: D. Tracy, The Achievement of Bernard Lonergan, New York 1970; D. Tracy, Analogical

Immagination Christian Theology and Culture of Pluralism, New York 1981; D. Tracy, Modes of Theological Argument, in « Theology Today»,

1977 nº 33, pp. 370-390; D. Tracy, Revisionist Theology and Reinterpreting Classics for Present Practice, in T. Tilley, Post Modern

Theologies: The Challenge of Religious Diversity, New York 1996; D. Tracy, Analogical Immagination Christian Theology and Culture of

Pluralism, New York 1981; D. Tracy, Some Concluding Reflections on the Conference: Unity Amidst Diversity and Conflict?, in H. Küng D.

Tracy, Paradigm Change in Theology, New York 1991; D. Tracy, Blessed Rage for Order: The New Pluralism in Theology, New York 1975; D.

Tracy, Plurality and Ambiguity, San Francisco 1987; D. Tracy, The Question of Pluralism: The Context of the United States, in «Mid-Stream:

An Ecumenical Journal», 1983 nº 273; D. Tracy, Ethnic Pluralism and Systematic Theology: Reflections, in «Concilium», 1977 nº 101; cfr J.

Cobb - D. Tracy, Talking about God: Doing Theology in the Context of Modern Pluralism, New York 1983. Cfr etiam 4 J. Nash, Tracy’s

Revisionist Project: Some Fundamental Issues, in «American Biblical Research», 1983 nº 34, p. 240; D. Tracy, Foundational Theology as

Contemporary Possibility, in «Dunwoodie Review», 1972 nº 12, p. 3; D. Tracy, Blessed Rage for Order: The New Pluralism in Theology, New

York 1975, pp. 3, 9.

2 S. Sanks, David Tracy s Theological Project: An Overview and Some Implications, in «Theological Studies», 1993 nº 54, p. 709.

3 J. B. Cobb, Jr., Process Theology, in «Internet» 2011, http://www.religion-online.org/showarticle.asp?title=1489: «l. The Origins of Process

Theology. Most theology in the United States has been imported from Europe, sometimes from Great Britain, but more often from the

continent. However, from time to time indigenous movements have developed. Jonathan Edwards in the eighteenth century established the

New England theology, closely related to the Great Awakening. A major focus was on Christian experience, especially on conversion. It took

root and can be traced for a century as a major element in Christian thought in this country. In the nineteenth century Horace Bushnell

developed a quite independent and original way of thinking that was also widely influential. It also focused on Christian experience, this time

on growth into Christian maturity rather than on the crisis of conversion. Around the beginning of the twentieth century there was a

flourishing of indigenous thought. William James, John Dewey, and Charles Saunders Peirce are among the most important figures. For this

group, too, experience, was central. Although the term "process philosophy" did not come into use until the 1950's, retrospectively this

group can be claimed for the tradition. Its shared characteristics, in addition to a focus on experience, are its pragmatic, pluralistic,

relativistic, holistic, and naturalistic tendencies. Its members were radical empiricists, that is, empiricists who believed that experience is by

no means limited to, or originated in, sensation. During the same period, within the churches the pragmatic temper expressed itself in the

social gospel. This was the response of sensitive preachers in northeastern and mid-western cities to the consequences of industrialization.

The exploitation, especially of immigrant labor, was blatant, and many preachers were no longer willing to speak only of the personal

salvation of their flock or of the need of the newcomers for conversion. They were determined that the church support the efforts of the

exploited to organize and secure decent conditions. They read their Bible with new eyes and saw that their concerns followed from those of

the Hebrew prophets. They located Jesus' teaching of the Kingdom of God in this tradition, and gradually they developed their Christian

convictions into a theology. The best expression was Walter Rauschenbusch's A Theology of the Social Gospel (1917). There was a Baptist

theological school in Chicago oriented to the social gospel and sensitive to the radical empiricist temper. When John D. Rockefeller decided

to establish the University of Chicago, he built it around this seminary. Its president, William Rainey Harper, was the first president of the

university. The Divinity School of the University of Chicago was for at least sixty years the place where the tradition later called process

theology developed through its several stages».

4 K. Hamilton, Revolt against Heaven, Exeter 1965, p. 41: «Among the theologians of meaningfulness, Ogden is the who has shown himself

to be most alert to the roots of the theological outlook he has adopted. At least, he is the most tradition-conscious (with the exception of

Tillich, whom Ogden almost certainly follows at this point). He explains that, if we take Bultmann's call for demythologizing seriously, we

have put ourselves on one side of a two-hundred-year-old controversy. We have aligned ourselves with the "liberal" tradition in

Protestantism that is associated with the names of Schleiermacher, Ritschl Herrmann, Harnack, Troeltsch, Schweitzer, and the early Barth. as

well as with the American liberals and neoliberals - Bushnell, Clarke. Rauschenbusch, "the Chicago school," Macintosh, the brothers Niebuhr,

and Tillich (1)».

((1) Christ without Myth, p. 133.)

5 A. Kee, The Ways of Transcendence, London 1971, p. 36: «No single author or work can be taken as representative of the school of Process

Theology, and there is no particular justification for concentrating attention on one essay written from this standpoint. Of the many works

which could have been examined 1 I have selected one which is manageable in the context of this discussion, and one which has been rightly

praised by those who find this approach helpful. Schubert Ogden delivered a lecture entitled The Reality of God 2 in 1965, during the

dialectic period of the Death of God movement in America. It sometimes appears that even more important than coming to the right answer,

is finding an adequate way of formulating the right question. Ogden considers that the way in which the problem of God was approached

precluded an adequate solution. In his essay, he sets out to reformulate the question, confident that a new and satisfactory way of speaking

about God can be found indeed has already been found but not yet taken seriously throughout the theological world».

((1) E. g. D. Williams, The Spirit and the Forms of Love (1969)); P. Hamilton, The Living God and the Modern World (1967); J. B. Cobb, A

Christian Natural Theology (1966). / (2) Published in Schubert M. Ogden, The Reality of God, and Other Essays, S.C.M. Press, London, 1967.)

178

dell’impresa teistica o del linguaggio su Dio 1. In questo senso, non si avrebbe qui una teologia

ateistica o un ateismo teologico, ma piuttosto una teologia anti-teistica 2. Vi sono dunque diversi

tipi di radicalità così come diversi livelli di tipologia teologica oggi: i radicali formerebbero

comunque un gruppo non effimero in questo quadro 3. Le osservazioni stizzite di qualche

esponente teologico non dovrebbero confermarsi in pieno 4, ma fanno eco all’allarmismo dei

vertici ecclesiastici negli anni 60- 70 5, focalizzando una volta ancora l’intero dibattito su una

1 J. Macquarrie, Twentieth-Century Religious Thought, London 1971, pp. 390-391: «The controversy in the United States over the death of

God stimulated efforts towards a better formulation of theism. The tradition of Whitehead and Hartshorne was notably continued and

developed by Schubert Ogden (b. 1928), especially in his book The Reality of God. Closer to Tillich was the work of Langdon Gilkey (b. 1919).

Applying the methods of phenomenological analysis to ordinary secular experience, he argued, especially in the book Naming the Whirlwind,

that such analysis reveals depths of ultimacy and sacrality which demand expression in God language. Though different in method, a

somewhat parallel approach is found in the work Sociologist Peter Berger (b. 1929). He has maintained, in a book call appropriately A

Rumour of Angels, that sociological investigation uncovers but does not exhaust certain areas of the human experience which function as

'signals of transcendence'».

2 Th. C. Owen, A new systematic theology in a phenomenological mode: Divine Empathy: A Theology of God. By Edward Farley (Minneapolis:

Fortress Press, 1996, xvi + 320 pp.), in «Internet» 2005, http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3818/is_199804/ai_n8785548: «Then

Farley takes up "anti-theism" which is not atheism but rather the criticism of the classical Catholic theology of God. First there are the intra-

theistic critiques which attempt to clarify some of the ambiguities or take the form of neoclassical or process theism. Then there is the re-

symbolizing of such themes as sovereign rule, the demythologizing of alleged literalism and dualism, and the more serious critiques by

radical theology, deconstruction, and what Farley calls religious-philosophical anti-theism. Farley discusses the latter at some length in its

Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish forms (Buber, Rosenzweig, Lévinas). It refuses to think from the world to God, to think the being of God, and

to think the relation between God and the world. Farley wonders whether this rift between religious-philosophical and classical theism is as

wide as it seems at first, and concludes that at the heart of the former lies an element of authority, which leaves their relation complex and

obscure».

3 T. W. Brock, Radical Theology and the Death of God by Thomas Altizer and William Hamilton. American Theology, Radicalism and the Death

of God by William Hamilton, in «Internet» 2005, http://www.religion-online.org/showchapter.asp?title=537&C=585: «There are four camps;

the lines dividing them are porous, and some have pitched their tents on the boundaries. A large group still feels at home in the ecumenical,

Barthian, neo-Reformation tradition. Most of the American contributions to the ecumenical movement lie here, as do most of the Protestants

engaged in dialogue with the Roman Catholics. This position may become more important in disciplines ancillary to theology than in

theology itself; as liberalism left systematic theology and went to live with psychology of religion and Christian education for a while, so neo-

orthodoxy may have its immediate future in history of doctrine, Old Testament and perhaps in ethics. For instance, one of the most

interesting recent events was the reception in some circles of Harvey Cox s elegant pastiche The Secular City (pop Barth?) as a new language

for this neo-orthodox tradition. This admirable book came, one might say, as a cool glass of salt water to the thirsty Establishment. The

second group contains the Bultmannians and new hermeneutics people; a great deal of solid New Testament work is, of course, being done

under this banner. Theologically it is exciting and unstable, particularly at the left margin, where a drift to the third or fourth groups is

discernible. Third is the group which is hopeful for a new kind of natural, metaphysical or philosophical theology. The ontological argument

is being restudied; so are Wittgenstein, Whitehead and Heidegger. Looking at this growing, enthusiastic and intelligent group, it is clear that

liberal theology is by no means as dead as some of the older funeral orations implied. The fourth is the radical or "death of God" theological

group. A number of names are given to this fourth group, none of which is entirely satisfactory. One hears of the "new" theology, the secular,

the radical, the death of God theology. I think radical is perfectly adequate, though there is often a kind of arrogance in ascribing this to

oneself. However, if it is used, it should be carefully distinguished from other forms of radicalism. We have radical radicals today; they are

non-moderate and in general can be identified by their attitudes toward James Baldwin, LeRoi Jones, Martin Luther King and civil

disobedience. There are sexual radicals, and they, too, are easy to spot. They are radically uninterested in pre-marital sexual chastity; they

believe in being radically open to others, and they are firmly against "Puritanism." We also have the ecclesiastical radicals who say critical

things about the present form of the institutional church. Members of this group write study books for the student movement and speak

about secular, worldly and non-religious theology. (They are often confused with the theological radicals for this reason)».

4 A. Dulles, The Resilient Church. The Necessity and Limits of Adaptation, New York 1977, p. 19: «A progressive Dutch theologian, a decade

ago, wrote a book entitled The Grave of Cod. (1) His thesis was that the institutional Church, by its self-defensiveness, was largely

responsible for the so called "death of God." In my view the title of this book could appropriately be transferred to the masochistic Church of

secularization theology. In that Church God never really lived. Secularistic theology was a product of the same movement as the "God is

dead" theology, and is now as dead as the atheistic Christianity by which it was accompanied».

((1) R. Adolfs, The Grave of God: Has the Church a Future? (London: Burns and Oates, 1967).)

5 J. Grootaers, De Vatican II à Jean Paul II, Paris 1981, p. 17: «Mais, à l'encontre de ces phénomènes, il s'en produisit d'autres qui ont fait sur

l'entourage du Pape et plus tard sur Paul VI lui-même l'effet de symptômes alarmants; citons, notamment, l'énorme succès de la théologie

popularisante du Dieu est mort, de Robinson, les débats publics sur la signification de l'Eucharistie et, non des moindres, les disputes autour

du Catéchisme hollandais paru en octobre 1966, qui suscitait par ses traductions en langues étrangères des remous dans des cercles

toujours plus larges. Il n'en fallait pas davantage pour que certains porte-parole des milieux préconciliaires de Rome établissent un lien

causal évident entre la dynamique de Vatican II et la crise de foi qui s'annonçait».

179

questione di equilibratura interna senza affrontare davvero la scommessa di un autentico dialogo

con il mondo nel suo incerto percorso 1.

I

LE IMPLICAZ IONI DI UNA RISPOSTA DI VERIFICA

TEOLOGICA

La teologia radicale parte dalle insufficienze della teologia della Parola, o cioè dall’assenza

di una autentica attenzione per coloro ai quali è indirizzata la Parola 2. Ma l’intento radicale

costata anche che gli ispiratori della teologica dialettica non hanno portato fino alle sue ultime e

radicali implicazioni la stessa chiave dialettica nella coincidenza degli estremi opposti 3. Si tratta

infatti di una affermazione -per così dire- di principio. Dopo aver richiamato l'attenzione sulla

presenza in campo del primo Protagonista Dio, si impone adesso l'eco dell'altro protagonista,

dell'interlocutore, cioè del partner umano. Esso non è l’essere umano in se, ma l'interlocutore deve

essere considerato nella sua concretezza: cioè la persona umana di oggi. La teologia radicale

cercherà di cogliere tutto ciò che coinvolge l'intento umano oggi. Si passerà dunque, per far breve,

dall’intransigente trascendentalismo al ‘nuovo immanentismo’ 4. La corrente radicale include –poi-

un campo d’interesse dei suoi ispiratori per lo studio comparativo delle religioni dell’umanità

seguendo tra l’altro M. Eliade. Una finestra si apre così verso l’intento finale di questo livello della

teologia del XX-XXI secolo, la teologia pluralista con la sua riarticolazione teologica (vedere infra,

volume III, parte I, sezione B).

Queste valenze porteranno la prospettiva radicale a una severa verifica dell'espressione di

fede. Si passerà rapidamente dalle scienze positive alle scienze umane, per sottolineare come

l'attuale presentazione cristiana manchi di incisività e quanto le comunità cristiane abbiano poca

1 A. Kee, The Ways of Transcendence, London 1971, p. 73: «The Catholic Church can be relied on at present to provide copy when there is no

world crisis to hand. But the whole aggiornamento movement is exactly that, it is not the Catholic Church giving a lead to the secular world,

but rather an example of a near fatal and disintegrating trauma by which that church has been dragged kicking and fighting into the first

(not second) half of the twentieth century. The issues reported tend once again to be purely internal to the life of the Church, and do not

make belief any more possible».

2 W. Hamilton - T. Altizer, Radical Theology and the Death of God, New York 1966, p. 45: «Many understandably feel that Karl Barth's

theology, for example, is out to date, because Barth has always refused to make the question of the receiving subject a primary question».

3 J. W. Montgomery, A Philosophical-Theological Critique of the Death of God Movement, in B. Murchland, The Meaning of the Death of God,

New York 1967, p. 33: «From modern Protestant theology Altizer has acquired his basic understanding of Christianity. Sören Kierkegaard has

contributed the dialectical method: "existence in faith is antithetically related to existence in objective reality; now faith becomes subjective,

momentary, and paradoxical." (1) Rudolph Ott (2) and Karl Barth have provided a God who is wholly transcendent -who cannot be adequately

represented by any human idea. But Barth, Bukmann, and even Tillich have not carried through the Kierkegaardian dialectic to its consistent

end, for they insist on retaining some vestige of affirmation; they do not see that the dialectic requires an unqualified coincidence of

opposites. If only Tillich had applied his "Protestant principle" consistently he could have become the father of a new theonomous age».

((1) T. Altizer, "Theology and the Death of God," The Centennial Review, VIII, (Spring, 1964), 130. It is interesting to speculate whether

Jaroslav Pelikan is fully aware of the consequences of his attempts theologically to baptize Kierkegaard (From Luther to Kierkegaard) and

Nietzsche (Fools for Christ). / (2) Cf. Altizer, "Word and History," Theology Today, XXII October, 1965), 385. The degree of current popular

interest in Altizer's radicalism is indicated by the fact that the Chicago Daily News adapted this article for publication in its Panorama

section_(January 29, 1966, p. 4).)

4 F. T. Trotter, Variations on the 'Death of God', Theme in Recent Theology, in B. Murchland, The Meaning of the Death of God, New York

1967, pp. 19-20: «The New Immanentism. J. J. Altizer is a student of Joachim Wach and Mircea Eliade. the great historians of religion. Altizer

emphasizes the dialectical accents of Nietzsches doctrine of Eternal Recurrence. The proclamation of the death of God is also the

announcement of the possibility of human existence. “A No-Saying to God (the transcendence of Sein) makes possible a Yes-saying to

human existence (Dasein, total existence in the here and now). Absolute transcendence is transformed into absolute immanence.” 1 Altizer

calls for a “genuinely dialectic” theology that refuses to be gnostic because of its affirmation of the present and likewise refuses to be

dogmatic because of its negation of the non-dialectical past».

((1) Thomas J. J. Altizer, “Theology and the Death of God”, The Centennial Review, VIII, 2 (Spring 1964), 132.)

180

credibilità. La verifica sarà severa per il campo cristiano. La pietra d’inciampo per la testimonianza

di fede oggi sarà l’impianto ecclesiale stesso nella sua inadeguatezza arcaica 1. In tal senso, si

potranno rintracciare segni di aggressività nella riflessione radicale. Ma questa aggressività

indirizzata contro manchevolezze cristiane non esaurisce tutta la prospettiva radicale.

L’accentuazione della negatività verso l’affermazione formale di Dio conterrebbe, però, un intento

dialettico specifico: o cioè la coincidenza degli estremi opposti, in altre parole negando

radicalmente Dio si ritrova il Suo mistero 2. La negazione di Dio prende la forma di una negazione

del “Dio crudele” avvertibile nel mistero insostenibile della croce 3. Vi è un altro aspetto che

sembra farsi vivo, e che distingue poi il pensiero radicale dalla teologia liberale: si tratta

principalmente del tono disincantato che risuona attraverso le formulazioni della morte di Dio.

L'insofferenza, verso la situazione cristiana presente, non sfocia in un entusiasmo senza riserve

per il mondo. L’interlocutore è responsabile e consapevole, ma questa responsabilità non appare

allegra. Più andrà avanti (vedere parte II, sezione B, cap. II, n° 3, Il “Noi della città secolare”) la

formulazione e l'approfondimento della corrente radicale, più il peso della responsabilità si farà

poco attraente. Volendo essere totale verifica, la teologia radicale finirà col diventare una

questione sulla stessa sopravvivenza dell'umanità, e non tanto sulla vita o morte di Dio. La morte

di Dio colpisce ancora più incisivamente se la si considera dopo alcuni decenni di percorso. La

morte di un Dio della religione ha visto nascere una circolazione di diverse religioni in una

convivenza obbligata e dettata dai ritmi di scambi, di spostamenti, di diaspora, di immigrazione ed

emigrazione assai estesa. In modo caratteristico, questa nomadificazione attraverso le religioni e

le fedi ha sembrato all’imbrunire del XX secolo- rinforzare la religiosità della(e) religione(i) o la

cultualità dei culti presso i propri aderenti, più che uno scioglimento dei loro ripiegamenti. La

teologia della morte di Dio appare tanto più paradossale nel confermare chi non è interessato alla

problematica della fede e nell’essere contrastata da chi porta a modo di stendardo la propria

religiosità. I protagonisti o gli osservatori del fenomeno chiamano al passaggio dalla morte di Dio

1 R. McAfee Brown, What does the Slogan Mean?, in B. Murchland, The Meaning of the Death of God, New York 1967, p. 177: «Amid many

things that are unclear in the book, one thing is absolutely clear. This is Altizer’s total disavowal of the church –and, indeed, so it would

appear, any form of community. He makes evident from the beginning that the Christian church is the real roadblock in the way of an

understanding of “radical” Christian faith. “The churches are inadequately equipped to face such a challenge.” Christian faith has gotten

hogged down in “an increasingly archaic ecclesiastical tradition” (p. 9)».

2 T. W. Brock, Radical Theology and the Death of God by Thomas Altizer and William Hamilton. The Death of God Theologies Today by

William Hamilton, in «Internet» 2005, http://www.religion-online.org/showchapter.asp?title=537&C=587: «Apparently the answer comes in

Altizer s use of the Kierkegaardian idea of dialectic, or -- what comes to the same thing -- in his reading of Eliade s version of the myth of

the coincidence of opposites. This means that affirming something passionately enough -- in this case the full reality of the profane, secular,

worldly character of modern life -- will somehow deliver to the seeker the opposite, the sacred, as a gift he does not deserve. At times,

Altizer walks very close to the gnostic naysayer whose danger he ordinarily perceives. His interest in the religious writing, such as it is, of

Norman 0. Brown is a sign of his own religious gnostic temptations. Brown not only mounts an un-dialectical Freudian attack on the profane

and the secular, he sees both history and ordinary genital sexuality as needing to be radically spiritualized and transcended. His religious

vision, both at the end of Life Against Death and in his more recent thought, is mystical, spiritual and apocalyptic. This temptation is not a

persistent one in Altizer, and in one important section of his book he makes the most un-gnostic remark that the sacred will be born only

when Western man combines a willing acceptance of the profane with a desire to change it».

3 B. Mondin, Teologie del nostro tempo, Alba 1976, pp. 152-153: «L’assolutizzazione della croce, quale principio architettonico ed

ermeneutico della storia della salvezza, già visibile negli ultimi scritti di Dietrich Bonhoeffer, diventa il carattere dominante del movimento

teologico noto come «teologia della morte di Dio», soprattutto nel suoi due esponenti principali, Hamilton e Altizer. Secondo HAMILTON il

mistero della croce oggi è diventato più fitto che mai, e penetra profondamente ogni aspetto della fede e della pratica cristiana. Non soltanto

ci sconvolge l’evento della morte di Cristo, ma ci tortura il cumulo di dolori e di sofferenze che pesa sull’umanità attuale. Questo ci fa

pensare «che Dio si sia ritirato dal mondo e dalle sue sofferenze e ciò ci porta ad accusarlo o di indifferenza o di crudeltà. Ma in un altro

senso, Egli viene sperimentato come un peso e una ferita da cui vorremmo essere liberi. Per molti di noi che ci chiamiamo cristiani, perciò,

credere nel tempo della “morte di Dio” significa ch’Egli presente quando non Lo vogliamo ed in modo che non vogliamo, mentre invece non è

presente quando Lo vogliamo» 1».

((1) The Gospel of Christian Atheism, Westminster Press, Philadelphia 1966, pp. 102-103 (trad. It. Il vangelo dell’ateismo Cristiano, Ubaldini,

Roma 1969.)

181

alla morte della teologia come necessario silenzio attraverso il quale bisogna passare 1. Tra

istituzione ecclesiastica (religiosa) e cultualità, la teologia radicale appare come un tentativo

disperato di continuare a fare teologia cristiana dopo che siano spariti sia la configurazione

religiosa sia la cultualità rituale previa 2. Si tratterebbe meno una questione di teologia cristiana

non metafisica che di una teologia cristiana senza Dio. Lo stile ed il tono della teologia radicale

appare ad alcuni come una espressione apocalittica dell’intento teologico: cioè una specie di

ipnosi della fine, fine che si sta consumando e vissuta in modo traumatico, coinvolgendo questa

teologia nella fine stessa 3. La corrente o la nebulosa apocalittica è presente attraverso tutto il

percorso della teologia del XX-XXI secolo (vedere volume III, parte IV, sezione B, gli orientamenti

apocalittici). Questa teologia radicale potrebbe essere descritta come “hard theology” dalla

stilistica che ha scelto, alla quale potrebbe rispondere una “soft theology” 4.

II

LA TEOLOGIA RADICALE E LA DINAMICA TEOLOGICA

DEL XX SECOLO

L’avvio del dialogo e dei confronti comparativi tra le teologie del XX-XXI secolo vede

formularsi una prima risposta di verifica di fronte alla corrente ‘fondante’ del percorso teologico

1 T. W. Brock, Radical Theology and the Death of God by Thomas Altizer and William Hamilton. America and the Future of Theology by

Thomas J. J. Altizer, in «Internet» 2005, http://www.religion-online.org/showbook.asp?title=537&C=586: «Like all thought, theology, too,

must find its ground in that terrible "night" unveiled by the death of God. It must return to that mystical "dark night" in which the very

presence of God has been removed, but now that "night" is all, no longer can theology find a haven in prayer or meditation. Dietrich

Bonhoeffer has said that we must not reach the New Testament too quickly, but the time has now come to say that theology can know

neither grace nor salvation; for a time it must dwell in darkness, existing on this side of the resurrection. Consequently the theologian must

exist outside of the Church: he can neither proclaim the Word, celebrate the sacraments, nor rejoice in the presence of the Holy Spirit. Before

contemporary theology can become itself, it must first exist in silence. In the presence of a vocation of silence, theology must cultivate the

silence of death. To be sure, the death to which theology is called is the death of God. Nor will it suffice for theology to merely accept the

death of God. If theology is truly to die, it must will the death of God, must will the death of Christendom, must freely choose the destiny

before it, and therefore must cease to be itself. Everything that theology has thus far become must now be negated; and negated not simply

because it is dead, but rather because theology cannot be reborn unless it passes through, and freely wills, its own death and dissolution».

2 C. Geffré, Un nouvel âge de la Théologie, Paris 1972, p. 70: «Ainsi il faut comprendre la théologie de la mort de Dieu comme une tentative

désespérée de continuer à tenir un discours théologique chrétien, alors même qu'on accepte comme une donnée culturelle inéluctable

l'impossibilité d'un langage signifiant sur Dieu. En face d'une telle théologie, le vrai débat ne consiste donc pas à s'interroger sur la légitimité

d'une théologie non métaphysique, mais sur la possibilité même d'une théologie chrétienne qui ne parle plus de Dieu. Pour nous, une

théologie chrétienne sans Dieu est un non-sens. Ou bien, elle n'est plus qu'une anthropologie. Et on pourrait montrer qu'il est contradictoire

de continuer A se réclamer de la Seigneurie du Christ sur le monde et sur l'homme et d'affirmer en même temps la totale autosuffisance de

l'homme séculier ainsi que son impossibilité à poser le problème de Dieu».

3 J. Mann, Sof(T) Theology, in «Internet» 2005, http://www.fountain.btinternet.co.uk/theology/soft.html: «Can we hear radical theology as an

apocalyptic tone announcing the end of realism, an end that has already occurred secretly and will soon be made present to the whole world?

Radicals love the End, it is at the centre of their passion and they cry "the old world is ending, we are preparing for religious belief in the

third millennium!" I think that sometimes apocalyptic exuberance can cover a little melancholic regret at what is ending. To what end do

radicals announce the End? After the End, what then? Is radical theology part of the old world? Will it end at the End? Perhaps it would help if

we noted two important traits of realism. Firstly it has to have some sort of dogma, because the theological language is determined by a

supernatural reality, and secondly it has to be fairly systematic, because being the Truth it has to apply to Everything. Doesn't radicalism

itself contain a shadow of these two traits?... Even radical theology is too epic, too grandiose, too loud. The union between the self and God

is a soft, rhythmic union. Feel God's soft breath, for the breath and the mouth (of God) are the breath of love and grace, a watery breath, an

application of the head to the mouth, infusing softness, the rhythm of inhaling and exhaling. Soft theology, like the soft penis, penetrates

nothing and signifies nothing».

4 J. Mann, Sof(T) Theology, in «Internet» 2005, http://www.fountain.btinternet.co.uk/theology/soft.html: «This rather determined and rigid

way of theological thinking I would like to call "hard theology". This term has a number of resonances, perhaps the most obvious being

"intellectually difficult" (for example, when the Bishop of Durham was on Wogan he explained what he believed and Wogan replied "I didn't

understand a word you said"). However the main significance of the term hard is as in structured, fixed, ordered, closed. Soft theology, which

I shall now try to picture, is fluid, seductive, opaque. It's already happening, but not as a movement, not as a regime, not as a manifesto. Soft

theology is fictional theology, poetic theology: it's theology without theology, Christianity without Christianity».

182

rinnovato dall’inizio del secolo: la “teologia radicale” o “la teologia della morte di Dio”. Occorre

distinguere –ovviamente- questa chiave teologica da quello che era la ‘teologia liberale’ del XIX

secolo perché alcuni rapidi accostamenti sono stati proposti in tal senso. Le differenze dovranno

essere chiarite nell’ambito del nostro percorso (cfr infra). La filiazione rinvia innanzi tutto alla

discussione iniziata dagli stessi discepoli di K. Barth nel ribaltamento delle prospettive che tentano

di articolare, con la priorità che vogliono mettere in anteprima delle loro preoccupazioni: il

riconoscimento dell’emancipazione umana odierna e le sue implicazioni per l’ambito della fede.

A.

QUALI FONTI ISPIRATIVE NELLA VERIFICA DELLA

TEOLOGIA RADICALE E QUALE SEGUITO

TEOLOGICO?

Si fanno talvolta risalire le radici filosofiche della ‘morte di Dio’ al XIX secolo, tra Kant,

Ritschl e Nietsche 1. C’è però da chiedersi se il rinvio più significativo sia quello del solo ambito

filosofico o se fa parte di una volontà di verifica più estesa. In senso del tutto generico, si potrebbe

dire che la teologia radicale poggia letterariamente su autori come Petru Dumitriu (Dostoevskij o

Pasternak…) nel loro sofferto rapporto con l’Amore di Dio di fronte al male 2, mentre si dimostra

alternativa all’angolatura di M. Eliade che ispirerà piuttosto la teologia pluralista, pur non essendo

strettamente teologo egli stesso ma parte dell’intreccio interdisciplinare che nutre la ricerca

teologica più recente 3. Più ampiamente ancora, non è privo di senso vedere una sorgente della

1 S. N. Gundry, Death of God Theology, in AA. VV., Elwell Evangelical Dictionary, etiam in «Internet» 2011, http://mb-soft.com/believe/

txn/deathgod.htm: «Also known as radical theology, this movement flourished in the mid-1960s. As a theological movement it never

attracted a large following, did not find a unified expression, and passed off the scene as quickly and dramatically as it had arisen. There is

even disagreement as to who its major representatives were. Some identify two, and others three or four. Although small, the movement

attracted attention because it was a spectacular symptom of the bankruptcy of modern theology and because it was a journalistic

phenomenon. The very statement "God is dead" was tailor - made for journalistic exploitation. The representatives of the movement

effectively used periodical articles, paperback books, and the electronic media. History. This movement gave expression to an idea that had

been incipient in Western philosophy and theology for some time, the suggestion that the reality of a transcendent God at best could not be

known and at worst did not exist at all. Philosopher Kant and theologian Ritschl denied that one could have a theoretical knowledge of the

being of God. Hume and the empiricists for all practical purposes restricted knowledge and reality to the material world as perceived by the

five senses. Since God was not empirically verifiable, the biblical world view was said to be mythological and unacceptable to the modern

mind. Such atheistic existentialist philosophers as Nietzsche despaired even of the search of God; it was he who coined the phrase "God is

dead" almost a century before the death of God theologians. Mid-twentieth century theologians not associated with the movement also

contributed to the climate of opinion out of which death of God theology emerged».

2 J. Kirkup, Petru Dumitriu. Writer whose cry to God met with silence, in «The Indipendent», in «Internet» 2011, http://www.independent.

co.uk/news/obituaries/petru-dumitriu-729913.html: «He was born in 1924 in the small Danubian village of Bazias, and started writing

essays in French at the age of 13. (The Romanians are outstanding speakers and writers of French.) During the Second World War he studied

philosophy in Germany. On his return to Romania, he became part of the movement of Socialist Realism and his writings received many

awards of merit. He became a reporter, founded a review, and was elevated to be head of a state publishing house, though he remained a

Communist without a party card. Utterly disillusioned by the Iron Curtain regimes and the Iron Guard's atrocities, he fled to the West, where

he lived from 1960, and where he composed his remarkable 1962 novel, Incognito (published in Britain in 1978). Then, suffering from the

spiritual depressions and pressures of exile and an alien culture, he stopped writing around 1969. His great self-confession, the result of

over 10 years of silence, with its Nietzschean title To the Unknown God, I translated for Collins in 1982. In it, he meditates deeply upon the

nature of God, and on the possibility of belief in a God who never responds to his appeals for help. He writes in a vigorous shapely style, rich

with philosophical allusions and illuminating quotations from his vast reading, all presented with easy scholarship, and interspersed with

brutally comic scenes from his childhood on the family farm. His five chapters on the nature of evil are among the finest ever written on this

intractable theme».

3 A. Kee, Ways to Transcendence, London 1971, p. 94: «The conclusion therefore comes as a surprise, Altizer is addressing himself to one

problem only, how can western men regain the sacred without turning back from their secular culture? His work is after all an alternative to

that of Mircea Eliade. But a concern for the sacred might be considered a peculiarly religions concern for any man. It would seem that for all

his hard words against Barth, Altizer is still very much within the Barthian orbit. The 'religion' that he rejects is, after all, only some forms of

183

teologia radicale nella dinamica sapienziale in seno alla fede, dall’Antico al Nuovo Testamento con

una focalizzazione non più sul popolo costituito (istituzionalmente) ma sulla persona interpellata

(interiormente) dal messaggio divino 1. Abbiamo qui un riferimento alla Sapienza (e l’ambito

sapienziale) dal contesto schietto di una fede nella sua istituzionalità. Al di là degli orientamenti

sofiologici, una teologia sofianica o sapienziale si presenta oggi come «lo studio del ‘tutto’» che

non esclude niente dal suo interesse, né di divino né di umano 2. Il pensiero radicale sembra

essere piuttosto ‘sostrattivo’ in quanto al linguaggio su ‘Dio’, purificazione estrema nella

riflessione teologica cristiana. È significativo che il pensiero sofianico si estenderà in una

trasversalità ulteriore di questo tipo (cfr infra la teologia radicale e la teologia sofianica). Un

parallelo si traccia tra l’esilio antico del Popolo di Dio e la sua diaspora in cui la chiave sapienziale

salva la propria appartenenza di fede senza configurazione formale e la ‘diaspora’ odierna nella

quale si prospetta la ‘teologia radicale’ 3. Nella chiave ebraica o biblica dell’intento radicale come

evocato da T. Greenfield si potrebbe rintracciare la correlazione tra l’affermazione religiosa di se e

la visuale sapienziale della ‘shekinah’ (poi nel prospetto islamico della ‘sakkinah’ di fronte alla

‘jihad’). Il linguaggio della fruttificazione interiore (shekinah) si troverebbe di fronte al linguaggio

dell’affermazione di se sia come ‘Tempio e culto’ sia come profezia prospettica.

religion (mainly oriental). He is still concerted primarily with providing a way to ‘return to God', But this is an extraordinarily reformist

position for one who was taken to be almost out of sight of traditional theology».

1 T. Greenfield, God is Love, God is Dead: Radical Theology as Wisdom Literature, in «Quodlibet Journal», Volume 2, Number 3, Summer

2000, etiam in «Internet» 2011, http://www.quodlibet.net/articles/greenfield-radical.shtml: «Radical Theology can be seen as a constituent

part of a 'Wisdom counter-culture' that has informed and reformed Christianity throughout history and is linked to Wisdom Literature

through a common view that they claim authority from the human experience of the way the world is, not the way the cultic tradition

requires it to be seen. This in turn makes both of them more questioning of God, than the credal cultic tradition and more likely to

experience despair and the remoteness of God. Wisdom literature is a distinctive form of writing found in both the Old and New Testaments.

Obviously the suggestion of distinction assumes another, or other forms, from which it is distinct. In relation to Wisdom this is principally

the writings that form the rest of the canon, namely, law, history and prophets. The central concerns of these writings are the origin, well

being, future and fate of Israel in a national / historical sense and the nation's unique relationship to God. The distinct nature of Wisdom

takes various forms, though one to alight on in relation to law, and history here, however, is its existential style. It is often concerned to

develop the idea of the individual and God, not Nation and God [1]».

([1] Clements, R.E. 1990, Wisdom for a Changing World, Berkeley: BIBAL Press, p. 22ff.)

2 Vedere i studi in proposito: in A. Joos, http://www.webalice.it/joos.a/SOPHIANIC_THEOLOGY_-_TEOLOGIA_SOFIANICA.html

3 T. Greenfield, God is Love, God is Dead: Radical Theology as Wisdom Literature, in «Quodlibet Journal», Volume 2, Number 3, Summer

2000, etiam in «Internet» 2011, http://www.quodlibet.net/articles/greenfield-radical.shtml: «'...radical Christians reject the 'orthodoxy' in

which truth is controlled by power, and dislike the mental numbness induced by canonical forms of words. In our view religious truth cannot

be canonized in fixed doctrines or forms of words.' [1] The relationship between Church and Radical Theology is complex, but, in short

Scripture and Faith, like the Temple and King of Israelite theology, would seem to be increasingly superseded by the Western mind's

adherence to the modern scientific myth. Increasingly scripture is undermined by literary analysis, history and archaeology, whilst Faith

undertakes periodic subtle, but nonetheless noticeable, shifts in position as changing world-views redefine the stage on which it is played

out. But if we dare to make the comparison between the experience of the Diaspora Jews and the experience of postmodern Christians as

both being disinherited strangers in a strange land, what does that tell us of the future of Radical Theology? There are, perhaps, two

possibilities. The first is that, just as Wisdom was included in the Canon and then defined as inspirational poetry rather than theology, so

may Radical Theology evolve into a mainstream Christian poetic, a poetic that would allow an expression of collective Christian anxiety in

response to a world that seemingly no longer allows its inhabitants 'old fashioned' or dogmatic faith in the certainty of an objective God. The

second may be to act in a subversive manner, effectively re-fashioning Christianity's historical-prophetic tradition into a more universal-

wisdom centred one. As Don Cupitt [2] and John Charles Cooper [3], among others, have demonstrated, the contrapuntal tradition in

Christian theology progressively, perhaps inevitably, develops orthodoxy out of former radicalism, and sometimes former heresy. Perhaps

Radical Theology is ultimately simply 'condemned' to be the next expression of the new orthodoxy of Christianity, a faith itself re-fashioned

by the triumph of narrative over dogma and Wisdom over history».

([1] Taken from 'The Radical Christian World-View' a lecture delivered by Don Cupitt at the 12th Annual Conference of the Sea of Faith

Network, Leicester 27-29 July 1999. A revised version was published in the organizations magazine, 'Sea of Faith' No. 38 Autumn 1999. / [2]

Cupitt's The Sea of Faith is a journey through modern western intellectual history which attempts to highlight through particular examples

(such as Darwin, Schweitzer and Kierkegaard) that the radicalism of previous generations becomes the orthodoxy of the future ones. / [3]

Cooper, J.C. 1968, The Roots of the Radical Theology, London: Hodder & Stoughton, pp. 17-55.)

184

Volendo riallacciare la nostra indagine nel percorso prettamente teologico, occorre tener

presente il legame ispirativo, anche se rovesciato, alla sorgente della teologia del XX-XXI secolo

nella stessa ‘paternità’ di K. Barth. Anche con K. Barth ci troviamo di fronte alla metodologia

purificante sotto forma della ‘crisi’ e della ‘via dialettica’.

B.

L'INEVITABILE RIFERIMENTO ALLA SVOLTA

FONDAMENTALE DELLA TEOLOGIA DEL XX SECOLO

CON K. BARTH. QUALE METODOLOGIA PER I

TEOLOGI RADICALI?

La ‘Parola morta’ (Dio) richiama l’intera questione della parola. La discussione si focalizzerà

sulla maturazione tra Wort e Sprache : parola e linguaggio, da K. Barth a G. Ebeling e a E. Fuchs;

Ebeling sarà l’avvocato dell’ermeneutica considerata non soltanto come metodo in appoggio

all’esegesi ma come intento metodologico di tutta la teologia, là dove la parola della fede non è

più compresa dal linguaggio umano abituale o contemporaneo 1. Dall’approccio riformista a quello

revisionista, che prolunga la via radicale, si accosterà Parola e Rivelazione come chiave della messa

in questione dei sistemi teologici chiusi nel loro esclusivismo assoluto 2, aprendo la Parola alla

lettura dell’esperienza vissuta con l’aiuto dell’ermeneutica 3.

C.

L’INEVITABILE COMPLEMENTO ALLA TEOLOGIA

RADICALE: L’INTUITO DELLA ANTROPOLOGIA

TRASCENDENTALE

Come vedremo nel volume II la teologia radicale ha delle attinenze con l’angolatura –nella

sua qualità di ‘corrente di convergenza’- della “antropologia trascendentale” ispirato da K. Rahner

(cfr infra). Tramite la figura di teologi come Lonergan (cfr vol. II, parte I, introduzione) il taglio più

esistenziale della visuale ‘trascendentale’ arricchirà l’approccio pragmatico radicale, con il

1 R. Gibellini, La teologia del XXº secolo, Brescia 1992, pp. 72-73: «Gerhard Ebeling (nato nel 1912), discepolo di Bultmann a Marburgo - con

il quale entrerà in vivace polemica a proposito del Gesù storico - è autore della densa voce Ermeneutica, che faceva la sua prima apparizione

nella terza edizione dell'Enciclopedia teologica evangelica Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart del 1959, e che ha largamente contribuito a

far conoscere il nuovo indirizzo teologico. Parola e fede. - E dello stesso anno una sua conferenza, Parola di Dio ed ermeneutica, in cui

formulava le prime linee di un programma di teologia ermeneutica. L'ermeneutica in teologia non può più ridursi ad essere la metodologia

dell'esegesi, anche se semanticamente dice lo stesso che esegesi, ma deve esprimere un compito di tutta la teologia. L'ermeneutica è la

dottrina del comprendere, ma in quanto tale essa si configura come dottrina della parola, perché il comprendere si articola in linguaggio e

parole: «In qualunque modo si voglia definire l'ermeneutica, resta vero che essa, in quanto dottrina della comprensione, ha a che fare con

l'evento della parola» 1. Ne consegue allora che l'ermeneutica teologica si configura come «dottrina della parola di Dio» (Lehre vom Worte

GotteS) 2. Essa si rende necessaria, quando la parola non è più veicolo di comprensione, ma risulta disturbata. t chiaro in questa

sottolineatura della parola l'influsso delle prospettive aperte dal secondo Heidegger e introdotte in teologia da Fuchs. Ma, mentre Fuchs usa

più volentieri una terminologia heideggeriana e parla di linguaggio della fede (Sprache des Glaubens), di evento-del-linguaggio

(Sprachereignis), e definisce l'ermeneutica teologica come dottrina (o teoria) del linguaggio della fede; Ebeling si attiene con più aderenza

alla tradizione linguistica della Riforma e parla generalmente di parola di Dio (Wort Gottes), di evento-della-parola (Wortgeschehen) e

definisce l'ermeneutica teologica come dottrina della parola di Dio (Lehre vom Worte Gottes)».

(1 G. Ebeling, Parola di Dio ed ermeneutica, in Parola e fede, 162. / 2 G.. Ebeling, ib., 172.)

2 D. Tracy, Blessed Rage for Order: The New Pluralism in Theology, New York 1975, p. 29.

3 D. Tracy, The Particularity and Universality of Christian Revelation, in «Concilium», 1990 nº 1, p. 111.

185

contributo di D. Tracy 1. Si farà strada una valorizzazione delle culture (con attinenze all’apertura

tillichiana, cfr parte V, sezione B) 2. La chiave religiosa rientra nel prospetto culturale nei simboli

maggiori o classici della sensibilità culturale 3. Il riferimento umanista ed interculturale rientra

nell’intreccio in cui anche le riflessioni ‘radicali’ hanno la loro ambientazione.

D.

LA FIAMMATA RADICALE E LA TEOLOGIA DELLA

GLORIA

Se prendiamo –poi- le correnti di salvaguardia del nostro livello di dialogo e confronto

iniziale “Dio o l’umanità”, il volume III si fermerà a certi tipi di ‘radicalizzazione’ sia nella

riaffermazione della fede, sia nella sua riarticolazione (cfr infra). La teologia della Gloria apparirà

come emblematica di questa salvaguardia ribadita nella discussione teologica tra il XX ed il XXI

secolo. Si caratterizzerà la teologia di Urs von Balthasar maggiormente come “ortodossia radicale”.

Essa sembra affine a quella di Milbanks 4. In tale modo la chiave estetica si presenta come una

teologia anti-radicale nel senso di un previo rifiuto della messa in questione radicale e della

‘catarsi’ teologica non sublimata in una sintesi articolata. L’intento della ‘gloria’ non potrà che

scontrarsi con quello rahneriano per il quale chi professa una visuale complessiva, armoniosa e

coerente di ‘bellezza’ cerca implicitamente una illusione idolatrica 5.

E.

LA CORRENTE RADICALE E LA TEOLOGIA

PLURALISTA

La teologia pluralista si afferma all’alba del XXI secolo come orientamento di

‘riarticolazione’ della prospettiva cristiana nel paesaggio interreligioso nel quale ci si comincia a

muovere la riflessione cristiana. La differenza maggiore tra le due correnti –radicale e pluralista-

ma anche la loro correlazione, va cercata nel diverso modo di cogliere la chiave di pluralizzazione

dell’esperienza umana. Il pluralismo è un dato fondamentale della società secolare o dell’intreccio

inter-religioso? Ovviamente, l’angolatura specifica darà anche una prospettiva propria ad ogni