Muzzolini 2006

Transcript of Muzzolini 2006

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

1/8

171ock Art Research 1006 Va/urne 23, NlIrnber 2, pp, /71-/78, A, MUZZOLlNIKEYWORDS: Classification - Style - Typology - Ethnic group - Chronology Sahara

CLASSIFYING A SET OF ROCK ART:HOW TO CHOOSE THE CRITERIA

Alfred Muzzolini

Abstract. In this, his final paper, the author sets out his procedures of classifying rock art, focusingon the rock art regions of the Sahara. The primary criteria he chooses in searching tor a typology, afteremphasising that the objectives of such endeavours need to be clearly defined, are presumed ethnicgroups, style, artistic groups and relative chronology, Although he is optimistic about the prospects ofsuch analyses, he cautions against simplistic deductions derived from subjectively perceived styles,and he emphasises the need for comprehensive interdisciplinary studies.

Classifying is distinguishing subsets, named dasses,within a set of elements. One has firstly to define the criteria according to which element belongs to a dass, then eachelement of the set is attributed to its relevant dass. Thisprocedure is commonplace in all scientific fields, and preHistory abundantly uses it as weIl. However, methods forclassification are diverse. As far as sets ofrock art are concerned some preliminary questions must be answered: is aclassification necessary, and for which object? Accordingto which criteria may we classify? Is a link possible, orprobable, from a dass of images to the makers of them?As the present writer is only familiar with the Saharanfield of research it will be easier for hirn to cite examples,when necessary, taken from this field. However, this paperintends to deal not only with the Saharan rock art, but alsoin a more general way with the dassification of any set ofrock art.1. Classifying for which objective?Rock art occurs in the form of hundreds of thousandsof extremely diverse pictures. Studying a region rieh inrock art images evidently begins with the survey of sitesand scenes represented. Already at this stage unavoidablesubjective choices take place: what constitutes or limits ascene, which features must be regarded as significantfeatures that will be used in later processing? Very soonthe necessity of classifying the elements of the survey appears evident. Whatever the aim of the study, ever sinceAristotles and even before hirn, science has been only aboutthe general. It would really be impossible to handle such amass of elements if at the very start we do not order theminto groups defined by some regularities, the groups beingfew enough to allow in the first place a discourse aboutthese groups. It will be possible later to go back to a uniqueelement induding special data.How can we make up these groups or classes, how to

dassify? Choosing the criteria that define a dass is reallYthe major epistemological problem, owing to the fact thatendless criteria seem to be possible, and each ofthem, or aconjunction of some of them, allows a classification(Bednarik 1994). But any classification, provided that it iscoherent, with criteria correctly defined, independent andnot redundant, is legitimate, 'exact': it cannot be said to beright or wrong. However, a classification can be more orless useful for the dassifyer 's aim. For instance a dassif ication of pictures according to their dimensions is easy,precise, 'exact' ... but useless for an archaeozoologist whowants to study the evolution of fauna, when it is noticedthat every species is depicted in nearly every dass of dimension.Therefore, we must firstly answer the question: what isthe objective of our study? Of course this will orientate uswhen choosing the discriminating criteria for our classes.Now, this objective unavoidably constitutes a personalchoice, or at least depends on the discipline practised. Forthe present author and his discipline, pre-History, the objective consists in understanding, reconstructing, describing the history ofsocial groups in the remote past. We knowthat rock art offers important remnants of this past. Con-fronted by a set of rock art the prehistorian will tr y to de-tect whether it possesses a structure. If its production ex-tended over a long time, it includes at least chronologicalstrata. If several human groups took part in this making,the set certainly refers to diffefent artistic, technologieal,sodal and symbolic worlds. A classification will aim atdistinguishing them.2. The ethnic groupIn order to reconstruct the remote past, how do prehistorians usually proceed, either in rock art or in whateverfield of their discipline?They start from finds, for instance a set of arrows is

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

2/8

172 Rock Art Re.earch 1006 - Va/ume 23. Number 2, pp. 171-178. A. MUZZOLlNlfound throughout an area: this cultural feature at least reflects a cultural group of arrow-users. However, this grouponly represents a very rudimentary group, because it isdefined by only one feature moreover, a widespreadfeature, not specific of a unique human group, Above all,such elementary groups may be only etic groups, i.e. unitscreated by prehistorians only for the requirements oftheirstudies but not in use among the humans studied. For instance these humans were probably not aware of there being a 'group of arrow-users'.But some cultural occurrences sometimes are specificof a unique group who was living in the area during a precise age: the ethnic group. The ethnic group can be definedas a group possessing, and conscious that it is possessing,either one or several cultural features that are original, i.e.exclusive and consequently specific of the group - or aconjunction of non-exclusive cultural features, but thisconjunction being original, hence specific of the group asweil. An example of the first case: all the arrows foundshow a special decoration pattern, termed a style unique,consequently specific ofthe group. An example ofthe second case: the arrows are trivial, but they occur in the samelimited area as other cultural features such as painted pottery, buildings under large natural shelters, human skullsartificially elongated (the example is taken from the American Indian Pueblo group). Neither the exclusive style northe exclusive conjunction of several non-redundant features is due to natural environment, and they cannot berandom occurrences either. Then it appears very likely thatthese cultural features are attributable to a cultural groupliving in this area, possessing these special features thatmarked its difference from the neighbouring groups, i.e.rnarked its identity: an ethnic group. Such a cultural groupI \ ~ t l ' l e v e d in this way should no longer reflect an intellectual construct ofthe prehistorian, but represents a category,termed emic, which really functioned in the concepts ofthe population under study.

Once the ethnic group has been defined by its discriminating cultural features, it can be described with all its features, discriminating or not. Afterwards it is possible to setit into a classification of ethnic groups. The descriptiongenerally includes chronological markers that allow thedefinition of the ethnic group relative to others. The finalresult is a chronological classification of ethnic groupscalled 'sequence', This operation, and sometimes its resultas weil, are also termed 'seriation'.Such an approach, classically practised in Prehistory,that consists in pcrceiving, defining, naming ethnic groups,then assigning to them a place in a sequence, is building aculture history. It was often criticised during the decadeswhen structuralism was triumphant. The main objectionwas that culture history too often confined itself to the description, by means ofa host offlint or ceramic types, ofamere mosaic of cultural units that belonged to very different patterns through time and space, while the studiesmissed the most important: the underlying structures otherthan material culture, structures that often transcend ethnic groups and extend beyond centuries. For many studiesearlier than 1950 such a criticism was justified. Since then,

however, ideas have evolved, and today the diatribes againsta crude culture history do not find their target so easily.Anyway, when starting whatever study of a pre-Historic set, consisting of either images or objects,. it is absolutely necessary to build a preliminary sketch of culturehistory, at least a rudimentary one, confined to determining the main cultural groups and their arrangement in chronological order. Such an elementary classification is indispensable even for a study with a structuralist objective, atleast in order to know, when faced with two groups, whichone could possibly have derived from the other. Claimingthat it might be possible to dispense with this preliminaryframework in order to 'go straight to meaning' is onIy fairwords, because in such a case synchrony and diachronywould remain intermingled. There would arise a seriousrisk of comparing thoroughly unrelated elements from different periods, different ethnic groups or different symbolicworlds, and yet detecting apparent but misleading relations.In short there would be a risk of mixing everything up.3. Criteria available for rock art cIassificationAs rock art study is a branch of pre-History, researchers working on rock art also adopt the approach we havedescribed. However, they come against a difficulty peculiar to rock art. Several ethnic groups, often nomadic, couldhave in the past occupied the same region or, worse still,the same site. Prehistorians frequently experience a similar situation when excavating a site, but in this case thestratigraphy is often visible and allows distinguishing thediverse occupation layers. On the contrary, the remains ofrock art, the images, are only juxtaposed; superimpositionsof images are very rare. Moreover, it is often difficult toclearly distinguish which one is overlying the other. Weare then in the same position as when prehistorians have attheir disposal, instead of stratified excavations, only surface finds where all flints and ceramic shards of the successive inhabitants ofthe site are mixed up (Bednarik 1995).Therefore, what we can at first do with rock art is onlyto detect and map repetitions or regularities, although wedo not even know whether they are ethnically relevant. Asfor ethnic markers, those currently used by anthropologistslanguage, religion, social structures etc. do not generally appear on rock walls. The choice of criteria for c1as-sification is restricted mainly to artistic markers that areconspicuous in the images but less surely discriminating inan ethnic sense. Some of them discriminate very little, forinstance techniques (polished outline, pecked surface, painting in ochre flat tint etc.), because most of them are toowidespread. Others are slightly more discriminating: forinstance special techniques (polychromy, engravings withdouble outline etc.) or unusual dimensions.Thematic markers are more difficult to use, even whenthey are exclusive, i.e. specific o a group, because theyare visible only in some pictures of the group. Thereforethey cannot be considered as real criteria far classifYinge.g. the buffalo, a specific thematic marker of the Saharangroup named Bubaline, cannot be a criterion for classification, because it does not help to discriminate a composition ofgiraffes. However, if a thematic feature appears fre

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

3/8

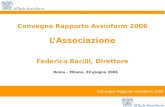

173ock Art Research 2006 - Volurne 23, Numbe,. 2. pp. /71-/78. A. MUZZOLINIquently and exclusively within a group thathas already been defined by other criteria,it can be used as a marker for the compositions in which it appears. Moreover, suchan exclusive recurrence will be a good cont'irmation of the coherence of the group,suggesting its emic validity. An examplefrom Saharan rock art is the 'flying gallop'chariots (Fig. 1). They belong to a groupnamed Caballine. They are not a criteriondet'ining the Caballine group - this groupis det'ined by diverse artistic markers - butthey are found only in compositions of thisgroup (Muzzolini 1994). They may thenconstitute an auxiliary thematic marker ofthe Caballine group. Other examples of suchthematic markers include headdresses,clothes, weapons, special objects and devices, physicaltypes of human figures, uncommon animals or also veryunusual themes (e.g. animal masks, therianthropes). Jt doesnot matter whether the meaning or the function of thesethemes are known or not, for the time being we can usethem only as markers specific of a group.

Finally, even chronological markers can be used as c1assification criteria if they include a discriminating value.For instance patinae - a group of dark-patinated petroglyphs can be distinguished from a group of buff-patinatedones - or the faunal spectrum - 'dry' or 'wet', steppe orsavanna faunas-may permit con'elation with dated knownclimatic episodes. Most importantly, an artistic criterionfor differentiating groups, and consequently for c1assifying them, appears in all regions and periods of rock al1 as amajor criterion, nearly always very discriminating: style.4. A major criterion of classification: style

Style is the way of doing something, and in art, whetherrock art or not, the way of representing an object, a figure,a scene, a symbol.

Hs advantage as a cultural marker comes from the factthat even when the subject represented is very common,widespread, and does not discriminate from an ethnic pointofview, its making had a unique author in a unique group.First of all, this author very often has a peculiar way ofrepresenting. Whatever theme Botticelli or Raphael painted- e.g. a Nativity, an Annunciation, that were very common themes - their 'hand', that is their manner of painting, is recognisable. In this case, style is the aI1ist's marker.

In other cases, mainly among social groups termed 'traditiona!', the artist is a member of a group that dictatesmore or less strictly not only which themes must be represented but also how they must be executed. The rules areoften adopted by the artist's social conformism, withoutany express constraint. The al1ist's freedom is not total anylonger, the group influences the way of representing. Inthis case style is a marker of the group.

Whether the artist's or the group's marker, style necessarily has some relation to the ethnic group that producedit. Maybe this relation is neither exclusive nor simple for example the group could have employed several con-

Figure 1. 'Flying gallop chariot', paintingfromImmeseridjen (Tassili, Algeria), Caballine school(L = c. 30 cm). (Photograph A. Muzzolini.)

temporary styles - nevertheless, it is a relation.Such a use ofthe criterion style as an ethnic marker has

been questioned. It has been asserted that the concept ofstyle is obscure and too subjective, because the defmitionof stylistic categories or their recognition among the images would depend too much on the observer's personalvision and culture. 1s such an objection valid?

We firstly acknowledge that a confusion frequentlyarises but it only relates to a wrong use ofthe word 'style'.Hence one must only avoid this confusion instead of dismissing the use of style. Let us repeat that style is the wayof representing, and not the thing represented. Unfortunately the archaeologicalliterature has sometimes wronglyused the word 'style' for what were only repetitions, onthe same rock wall or in the same region, of either favouritesubjects placed side by side, or subjects linked by somethematic and technical similarities. A typical example ofthis error is the so-called 'Panaramitee style' in Australia.1t refers to a pan-continental set of petroglyphs showingsimi1ar technique and often patina. But the themes represented are very simple, non-figurative or 'not very figurative', and often of geometric pattern - circles, dots, crescents, concentric ares, human footprints, 'kangaroo or emutracks', 'Iizards' and so on. Consequently they are aJwaysvery much alike. All subjects are abundantly repeated, butas there are not many 'ways of representing' a circle oreven a bird track, 'stylistic' variations are few, ifany. Suchan accumulation of similar subjects is an interesting factthat requires an explanation. However, it has no relationwhatsoever to the concept of style. When subjects are toosimple the danger occurs of finding them widespreadthrough the Australian continent - as it indeed occurredor even a1l over the world (McCarthy 1988; Bednarik 1995).

Even Leroi-Gourhan's 'styles' of Upper Palaeolithicrock art are only defined by a mixture of real stylistic features and thematic ones.

Style can indeed exist only when the artist has the freedom to allow a specific way of representing, so that the

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

4/8

174 Rock Ar t Research 2006 - Volume 23, Number 2, pp. 171-178. A. MUZZOLINf

Figure 2. 'Bowman' and 'floating figures', RoundHead school, pa in ting from Ti-n-Tazarijt (Tassili, Aigeria)(H offigures = c, 1 m), (Photograph A. Muzzolini)

work includes what we may call a 'stylistic charge'. Thisimplies a certain degree of complexity, thanks to wh ichcharacteristic touches, both peculiar to the artist or thegroup, and different from other artists or groups, can bemanifested. Circles, chevrons, dots and so on, even whenaccumulated, do not allow this, and style has nothing to dowith them.

Once this misapprehension about style has been setaside, the objection about subjectivity remains to be examined. Researchers admittedly define and identify stylesthrough qualitative evaluations: we are not dealing withpresence/absence statements, an appreciation by the observer occurs at least partially. However, even differentworks by the same artist show some variability, and artistsdo not strictly respect the standards imposed by the group.Therefore, it must be admitted that the 'way of representing' involves a degree ofvariability , moreor less wide, butunavoidable. The researchers have to appreciate this as weilas they can. Of course they run the risk of wrongly distinguishing two styles within the same group, or inverselyconfusing two styles that are really different but possesstoo much variability. In order to mini mise these risks theyshould only retain the stylistic groups that are definitelyclear-cut.

Such groups do exist when stylistic charge is significant. To argue against distinguishing, even only on the basis of style, Byzantine and Renaissance art, Romanesqueand Gothic sculptures, cubist and impressionist schools,would be unreasonable. Similarly in the Saharan field evena non-initiated person or a chance tourist will easily distinguish the paintings of the stylistic group we name RoundHeads (Fig. 2) from those of the Caballine style (Fig. 3).Such a stylistically grounded discrimination between twocJear-cut units should not be denounced as subjective.

To sum up: provided that we confine ourselves to setswith notable stylistic charge we may confidently use styleas a criterion for classifying rock pictures. And it will be amajor criterion because stylistic groups surely have somelink with ethnic groups - bearing in mind that the latterare the ultimate goal of our study.

5. Tbe artistic groupUp to now we have only explained which kind of criteria can be used for classifying a set of rock art. But which

criteria must we actually choose?Which criteria must be retained would be a more ap

propriate term. Indeed, we only note that some regularities, which suggest or impose the relevant criteria, arepresent in the set. Our choice is limited to the actual rangeof criteria that are visible locally. We notice particularlythat some thematic criteria are relevant only within a givenperiod.

Since the possible criteria are only those which possessa discriminating power within the set under study it standsto reason that there is no universal method available forclassifying rock art. A consequence of this is that the socalled 'universal automatic classifications' are mere utopias. Classifications ofthis kind have sometimes been tried,but unsuccessfully, They start from very many criteria chosen apriori - it should firstly be noted that such a choiceis arbitrary, it only emphasises the problem of choosingthe really relevant criteria (the 'crucial common denominator of a phenomenon category' of Bednarik 1994) andsetting them in hierarchical order. Then computers are setto work, measure distances and establish derivations between elements, scenes, groups etc., the final resultofwhichare 'exact' groupings of data, but most of them have noemic reality.

Rock art does not allow classifications similar to thesystems used in zoology or botany by way of a uniqueframework of criteria set apriori in hierarchical order. Scientifically-minded researcbers are accustomed to sets likepalaeontological sets in which an element derives fromanother, both having a common origin and the whole being liable to be sketched by way of a tree, or as sets ofelements that reflect quantifiable common parameters, thedistances ofwhich can be shown in a unique cluster analysis. These researchers are puzzled witb our definitions ofc1asses that use lists of criteria, which vary according toeach group. The main cause is that cultural features areinfinitely diverse, not permanent, and cannot be arrangedinto a hierarchical system of constant parameters.

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

5/8

175ock Arl Research 2006 Volume 23. Number 2. pp. 171-178. A. MUZZOUNIAll we can do is to subjectively choose some

repetitive features as criteria, because we thinkthey are significant from either the artistic orthe ethnic point of view (e.g. a deeply polishedoutline, painting in fl.at tint, a 'geometrie sche- '.matic style' clearly perceptible in all figures).We will consciously abandon the other features.Let us remember that the classifiers are free tochoose their criteria. For instance they may giveup a feature that is too ubiquitous and consequently does not discriminate very much (e.g.colour in paintings). There is no 'circular thinking' or illegitimate preconceived idea in theirchoices, they just want to choose between whatseems useful, or useless, for the classificationthey intend to propose. Such choices are as legitimate as for instance the choice of the zoologist who for classifying mammals chooses notto use the colour of the coat, or the choice takenby the historian who, among the myriads of datacollected, subjectively chooses only those considered as significant for exposing the thread ofhistory.

With criteria that are different for each group, what canwe expect to gain? We can obtain a few clusters of rockpictures that we will name 'artistic groups'. We are dealingwith apparently fairly homogeneous groups ofpictures thatare similar enough, within an acceptable variability area,and different enough from all other pictures. Such similarities and differences must be understood with respect tothe criteria adopted (in statistics this kind of classificationis termed 'typology').

If a marker chosen as a criterion is specific of an artistic group and present in all pictures of this group - e.g. aclear-cut style - it is sufficient to define this group. Theother markers are redundant, they are useful only for thedescription of the group. But if specific markers are lacking one can also choose an unusual conjunction consistingof non-specific criteria, and this conjunction may even include thematic criteria that are not manifest in all pictures.For instance, in the Sahara the conjunction technique ofdeeply polished outline + naturalistic style (two artisticcriteria) + dark patina (chronological criterion) defines theartistic group ofpetroglyphs named 'Naturalistic Bubaline'(Fig. 4). Moreover, as this group mainly represents animals, a fourth criterion, both thematic and chronologieal,may be added: archaie fauna of a savanna. These four criteria are not redundant but none of them is specific of thegroup. It is their conjunction that is specific, and sufficientto characterise a lot ofpetroglyphs. We can make them upinto a sui generis artistic group or cluster.

By using in this manner severallists of criteria it is possible to define several artistic clusters within the set understudy. However, in opposition to what produces a classification with only one Iist of criteria in a hierarchical system, it is very unlikely that the diverse groups we can identify by this way may constitute a classification in whichthe sum of the classes is exhaustive, i.e. conesponds exactly to the totality of the elements of the set under study.

Figure 3. Caballine figures, painting from Ti-nRassoutine (Tassili, Algeria) (H = c. 25 cm).(Photograph A. Muzzolini.)

Generally a residue will subsist, made of pictures that donot match with any of the lists of criteria used, and are tooheterogeneous to suggest the making-up of additional artistic clusters. This residue may be quantitatively important, but we willleave it as a pseudo-group, the 'unclassifiable pictures' - pending a finer classification, able to dealwith it and at least diminish it.

The present author has used this 'cluster method' inorder to classify the rock art ofthe central Sahara (Muzzolini1995). However, the Sahara is by no means a special case.One is reduced to this method, admittedly unsophisticatedand unfinished, when the set to study comprises several'layers' of pictures that correspond to several successiveethnic or artistic groups, without any possibility of physically discriminating these layers. Of course one is reducedto it only ifthe goal ofthe study is reaJ!y the prehistorian'sgoal, that is disentangling the diverse ethnic strata. If thegoal is different, other classifications, easier and exhaustive, are possible. For instance a kind of classification ispresented in many site or regional surveys. I t consists ofthe list ofthemes represented: humans, objects, and mainlythe diverse animals (cattle, giraffes, elephants etc.). However, in spite of the precise percentage indicated in addition for each of these merely thematic classes, such a classification is generally useless for prehistorians, becausemost animals, both wild and domestic, have been depictedby several ethnic groups. Therefore such classes do notallow distinguishing between the work of different ethnicgroups, or illuminate their history.

We must point out that trying to avoid tbe 'unclassifiablepictures' that this 'cluster method' discards is illusive. Inactual fact all researchers of the preceding generations at

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

6/8

176 Rock Art Research 2006 - Vo/ume 23. Number 2. pp. /7/-/78. A. MUZZOLIN/

L'igUlf::"-t! 1Jomestic cow (note the collar and pendant), petroglyphfrom Wadi Hagalas (Messak, Libya), NaturalisticBubaline school (L = c. 120 cm). (Photograph A. Muzzolini.)

work in Saharan rock art (Obermaier, Monod, Lhote, Morietc.) did also define artistic groups on the ground of diverse criteria. But as they were convinced that an 'exact'classification had necessarily to be exhaustive, they madea point of inserting somehow all figurations into one of thefour, five or six groups they had defined. This raised problems for many pictures, required many subjective, questionable - and questioned - attributions, diluted the definitions of groups or was even sometimes inconsistent withthem. In short, the coherence ofthe groups wasjeopardised.The present writer consciously abandoned such an ambition to classify all pictures and contents himselfwith a fewwell-defined and more credible clusters.

6. From the artistic to the ethnic groupOnce the artistic groups have been defined and de

scribed, the following step is noting the chronological markers that each of them nearly always includes. These markers are diverse according to regions 01' groups. For instance,chronoJogical markers commonly used in the Sahara arepatinae (the validity ofwhich is only statistical) and markers that can be given at least a rough date by other disciplines: e.g. the global spectra of fauna (archaic 01' recent),01' special animals (the buffalo, the oryx, the horse, thecamel etc.), the position of which in the overall climaticevolution 01' in the history of domesticated animals is knownfrom archaeozoology; devices or objects to which a placecan be assigned within a well-known technological evolution (e.g. bows, spears, swords, chariots), inscriptions denoting arecent period etc. Artistic clusters can by this waybe arranged into a chronological sequence, at least as faras relative chronology is concerned.

What can such an artistic-chronological sequence be

used for? Of course it may allow writing a history of artistic forms, independent of the history of the ethnic groupsthat produced these forms. But we also know that in thepast the various artistic forms nearly always had some relation with temporary social units - tribes, castes, sects,religions, peoples and so on - that they characterised.Therefore we can chiefly study whether the artistic-chronological cluster reflects some ethnic group.

How? No universal method is available for studyingthis problem either. Each case has to be discussed according to the particular circumstances. However, researchersfrequently use one argument, at least implicitly. It lies inthe fact that an artistic group is likely to correspond to anethnic one when it can be both established that:1. Its territorial range is all in one block and coincides

with some geographical border (e.g. the artistic groupextends on an entire massif, is surrounded by deserts 01'is Iimited by a river).

2. Chronological markers are included in the artistic cluster and they are coherent (e.g. the faunal spectrum reflects only savanna anima1s, all pictures have statistically identical dark patinae etc.).It must be acknowledged that in such cases there is at

least a presumption ofthe emic reality ofthe artistic group.It would indeed appeal' very surprising that a cluster defined, for instance, by way of stylistic criteria could be inkeeping with limits related to space, time or ecology, unless it corresponds to some discrete ethnic e lement boundedby the same space and time limits. Finding an original conjunction of artistic 01' thematic criteria only within a limited area, 01' within a distinct enough period, 01' within both,would be an unexplainable fact, unless a human group wasthe cause of this unusual concentration. By noting this spa

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

7/8

177ock Ar/ Research 2006 - Volume 23, Number 2, pp. 171-178. A. MUZZOLINI

Figure 5. Figures holding 'curved sticks', painting /rom Tahilahi (Tassili, Algeria), Iheren-Tahilahi school(H 0/a flgure = c. 30 cm). (Photograph A. Muzzolini.)

tial and temporal concordance for each of the features thatdefine the artistic cluster, the relevance of all features isconfirmed. So the relevance of the artistic cluster and itsemic reality are also confirmed aposteriori.

As an illustration, the artistic group of paintings named'Caballine' in the Sahara can be quoted (Muzzolini 1995:139). It includes almost only human figures and is definedby the following conjunction: figures painted in ochre (or,though rarely, white), flat tint (no internal details) + a veryspecific schematic style (Iarge shoulders depicted in frontview, very narrow waist and a simple vertical stroke to represent the head) + typical clothes (a short 'skirt' for menand a 'Iong dress' for women) + typical 'weapons': 'spears'and 'shields', never bows nor swords (Figs 1 and 3). Thesediverse features, jointly technical, stylistic and thematic,are found only on the rock walls of an area of c. 1000 by500 km, in fact only in the contiguous massifs of Tassili,Acacus and Hoggar. As we are dealing with nomadic populations in an arid zone, such an area does not appear immense. As for the se t ofweapons, it is often a good chrono-logical marker, it is coherent. The bow, a weapon commonamong the preceding Neolithic groups, now disappears andis replaced by more modern weapons - the spear and theshield. The sword, however, will be adopted only in thefollowing phase, the 'Cameline' period. We can reasonably conclude that the artistic cluster defined as theCaballine group corresponds to an ethnic group that livedon this limited territory. The typical clear-cut style of figures, with little variability area, even reflects a rather homogeneous group.

Other examples that define an artistic group likely tocorrespond to an ethnic group who inhabited a natural areaare the Saharan group of'Round Heads' (Fig. 2) that occupies an area of c. 400 by 100 km, all in one block within

the Tassili-Acacus massif, or the group ofpaintings namedIheren-Tahilahi group (Fig. 5) that does not extend beyondthe Tassilian massif, or the Australian group of Gwion figures (formerly 'Bradshaw figures') that are unknown outof the Kimberley (Walsh 2000).

Admittedly, the relation between artistic cluster and ethnic group is not always so clear as in these examples and isnot necessarily univocal. Fo r instance, the artistic clustermay correspond to only a fragment of the ethnic group. Amajor problem with which we are sometimes faced is howto interpret an artistic group found over a huge area. Anexplanation might be that the group has been defined byonly one criterion that discriminates too poorlY: such arethe artistic groups, able to include nearly everything, basedon a criterion of the kind' presence of cattle' or 'naturalistic style' alone. The literature has sometimes presented suchgroups, but it is apparent that the category used, obviouslyetic, is too wide, may involve a lot of ethnic groups, andtherefore is uninteresting for prehistorians. On the contrary,if the artistic group has been correctly discriminated by aspeciflc criterion or by several concordant criteria - whichimplies that its reality as an artistic cluster is undeniablebut extends over an area that appears too vast for an ethnicgroup, what is to be thought?

Too vast - what does this mean? There exists nogeneralisable standard. Population densities vary too much,they depend on the 'carrying capacity' ofthe biotopes, thusethnic groups in arid zones generally occupy areas largerthan those in temperate zones. Most importantly, the nomadic way of Iife can century after century shift or widenthose areas until they cover very large territories. A wellknown example is that of the Fulani. During the last millennium they have left their traces over a territoly that extends from the Sudan to the Atlantic, along a stretch of c.

-

8/8/2019 Muzzolini 2006

8/8

78 Rock Art Research 2006 . Voll/me 23, NI/mbe,. 2, pp. 171178. A MUZZOLiNIkm long and 1000 km wide. This area, albeit immense,

corresponds to the Sahelian savannas , between theIt was imposed by

s pastoral way of life.In the Sahara the cluster 'Naturalisti c Bubaline', al ready

mentioned (Fig. 4), perfectly defined as an artistic group,presents a problem ofthis kind (Muzzolini 1995: 97). It isfound from the Atlantic to Fezzan, but not beyond, mainlyin the Saharan Atlas, Tassili, Fezzan, besides some smallerdistricts in Hoggar. On such a very large area, which isvery diverse today, it appears difficult to imagine a uniqueethnic group with a uniform way of life. But the Naturalistic Bubaline group goes back to a wet period of theNeoJithic, when the entire Saharan land was a fairly continuous steppe that allowed a pastoral way of life. A firstexplanation might be an analogy with the case of the modem Fulani: the artistic group Naturalistic Bubaline couldreflect an ethnic group, ecologically defined, which in thecourse of centuries could have expanded over a stretch ofland which we find incredibly vast today. But there is anther, very different possibility: this artistic group mightorrespond to several ethnic groups, diverse and yet boundby some system, symbolic (language, religion etc.) or political, which was leading to similar expressions in the artistic domain. Such artistic communities formed by various ethnic groups are known in art history: for instance,the Hellenistic art, the Islamic art, the Romanesque or

of diverse Christian nations and solfwe confine ourselves to rock art, the conclusion about

he ethnic reality of the artistic c1ass will sometimes reain uncertain.

7. Comparing with other disciplinesIndeed we must not content ourselves with rock art. In

addition to the uncertainties about the relations betweensome artistic clusters and ethnic groups, the sequence ofartistic c1asses reflects only the human groups who did paintor engrave on rocks. In the Air mountains, for instance, incontrast to other Saharan regions, the earliest traces of rockart date only from the recent phases of the Holocene, although the massif was inhabited since the very beginningof the Holocene. Moreover, each artistic c1ass of our classification represents only a point in the past, continuity intime is seIdom manifest and hiatuses more or less important could have separated diverse clusters. In short, the rockart archives do not provide us with the complete story. Thesequence of artistic classes is only a rough image, neithersafe nor complete enough, of a true regional culture history. At best it is a best-fit hypothesis, valid untiJ it can be

called into question by data coming from other origins.The most obvious data relevant for that checking can

be found by comparing our artistic-chronological sequencewith sequences provided by other disciplines: the culturehistory inferred from archaeological excavations, the evolution of faunas described by archaeozoology, that of climates, the history of human groups known from ancientauthors and so on. Firstly, our cultural sequence must becompatible with these data obtained from other sources. Itwill eventually enlighten or complete them, mainly in domains like the symbolic world, the access ofwhich is difficult. It will also try to make use of those other sequences,while at the same time seeking confirrnations of the emiccharacter of our artistic clusters. There is a need of an exchange on all levels between the various disciplines thatcontribute to reconstructing the past. Through such an exchange the various disciplines strengthen each other. History has always been written by way of combining, checking, comparing the attainments of various disciplines.

In short, we must try through all available ways, mainlyby making the best of the data of all archaeological discipi ines involved in the same object, to understand the ethnic significance ofthe identified and classifled artistic clusters. Without a conclusion about this aspect the classification of artistic groups could remain, for the prehistorian, amere intellectual exercise, 'exact', but difficult to use, andperhaps useless.Postscript: This paper was first presented to the ThirdAURA Congress, held in Alice Springs in July 2000. Published here posthumously, it represents the author's finalmessage to the discipline of rock art research.

REFERENCESBEDNARIK, R. G. 1994. On the scientific study of palaeoart.

Semiotica 100(2/4): 141 ~ 6 8 . BEDNARIK, R. G. 1995. Taking the style out ofthe Panaramiteestyle. AURA Newsletter 12(1): 1-5.McCARTHY, F. D. 1988. Rock art sequences: a matter of clarification. Rock Art Research 5: 16-42 (with RAR Commentsby J. Clegg, B. David, N. R. Franklin, J. McDonald, L. Maynard, D. R. Moore, M. J. Morwood, A. Rosenfeld, R. G.Bednarik).MUZZOLINI, A. 1994. Les chars au Sahara et en Egypte. Leschars des 'Peuples de Ja Mer' et la 'vague orientalisante' enAfrique. Revue d'Egyptologie 45: 207-34.MUZZOLlNI, A. 1995. Les images rupestres du Sahara. ChezI'auteur, Toulouse.WALSH, G. L. 2000. Bradshaw art olthe Kimberley. Takarakka,Melbourne.

RAR 23-778