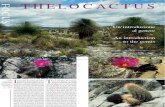

Cactus & Co. 2013 n. 1

-

Upload

andrea-cattabriga -

Category

Documents

-

view

247 -

download

18

description

Transcript of Cactus & Co. 2013 n. 1

XVII

2013

1Poste Italiane S.p.a. – Spedizione in abbonamento postale – d.l. 353/2003 (conv. in l. 27/02/2004 n.46) art. 1, comma 2, dbc Varese

Haageocereus decumbens

(Photo: Philippe Richaud)

2013

CaCtus & Co.

Vol. xvii · n. 1

www.cactus-co.com 4 GLOBETROTTER La vegetazione xerofila del Perù The xerophytic vegetation ofPeru Norbert Rebmann & Philippe Richaud

26 TAXA Sempervivum × luisae un nuovo, vecchio, ibrido a new, old, hybrid Mariangela Costanzo

60 CULTIVATION Aloe le sorprese non finiscono mai... the surprises keep on coming... Carlo Maria Riccardi

72 TAXA Yucca feeanoukiae spec. nov. Hochstätter Fritz Hochstätter

82 FOCUS Azorella compacta pianta endemica degli altipiani andini del Sud America an endemic plant of the Andean plateaux in South America F. Caceres De Baldarrago & Ignazio Poma

48 GLOBETROTTER Pediocactus nigrispinus crestato nel Colockum Game Range (WA, USA) Crested Pediocactus nigrispinus in the Colockum Game Range (WA, USA) Dixie Dringman & Jay Ackerley

5

– GLOBETROTTER –

peruvian landscapespaesaggi peruviani

La vegetazione

xerofila del

Perù

Nota editoriale. Questo articolo fa seguito all’articolo “La vegetazione xerofila del Perù”, dello stesso autore, apparso in Cactus & Co., vol. XV, no. 4 (2011), pp. 4-27.

Introduzione

La corrente fredda di Humboldt che scorre lungo la costa pacifica dell’America del sud e risale verso nord è responsabile delle condizioni climatiche desertiche di questa regione litorale, dando luogo ad una piovosità molto ridotta. Sulla costa del Perù le precipitazioni sono veramente modeste: a Chiclayo, circa 30 mm all’anno (in gennaio e aprile) e più a sud, a Pisco, circa 2 mm (in agosto e settembre).

Il clima dei deserti costieri

La striscia desertica costiera si estende a partire dal-

Editorial note. This article is a continuation of that on Peru’s xerophytic vegetation by the same author, pub-lished in Cactus & Co., vol. XV, no. 4 (2011), pp. 4-27.

Introduction

The cold Humboldt current, which flows north-wards along South-America’s Pacific coast, is respon-sible for the arid climate of this coastal region, since the cold waters give rise to very little rainfall. Pre-cipitation is scarce along Peru’s coast: at Chiclayo, some 30 mm a year (falling in January and April) and further south, at Pisco, only about 2 mm (in August and September).

The climate of the coastal deserts

The strip of desert runs along the coast from latitude

Thexerophytic vegetationofPeru

La vegetazione dei deserti costieri e delle lomas

Plants of the coastal

deserts and of the lomas

Haageocereus pseudomelanostele

Text: Norbert Rebmann.Photos: Philippe Richaud.

Parte II Part II

6

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

la latitudine 6°S fino al Cile, verso il 32o parallelo. Le zone elevate della regione costiera (lomas) sono bagnate dalla garua, nebbia causata dalla corrente fredda di Humboldt, che provoca condensazioni variabili sufficienti a consentire l’esistenza di una ve-getazione specifica.

Le regioni più basse, poste al di sotto del livello della garua, hanno una debole piovosità annuale: 25 mm a Lima, 20 mm a Mollendo e 0 mm a Arica, che si trova vicino alla frontiera cilena. Dunque le piogge di-minuiscono da nord verso sud, annullandosi del tutto presso la frontiera con il Cile.

Le zone più alte della pianura costiera (lomas), poste al livello della garua, ricevono una quantità di pioggia più rilevante: 40 mm a Tacna a 560 m di altez-za, 250 mm sulle colline di Lima a 220 m di altezza.

Un altro fattore importante è il grado igrometrico nelle zone

6° S down to Chile, at about the 32nd parallel. The coastal regions lying at higher altitudes (the lomas) receive moisture from the garua, sea mists caused by the cold Humboldt current, which produce variable amounts of condensation, sufficient to allow a spe-cific vegetation to survive.

The lower regions, lying below the garua, receive little annual rainfall: 25 mm at Lima, 20 mm at Mol-lendo and 0 mm at Arica, which is close to the bor-der with Chile. In other words, the rainfall decreases from north to south, and is absent entirely close to the Chilean border.

The higher areas of the coastal plain (the lomas), which reach the level of the garua, receive more rain-fall: 40 mm atTacna, at 560 m a.s.l., 250 mm on the hills of Lima at 220 m a.s.l..

Another important factor is the degree of humidity in the

La vegetazione

xerofila del

Perù

Tillandsia latifolia

7

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

costiere (deserti, lomas e valli) che è generalmente ele-vato, tra l’80 e il 95%.

Il clima di queste regioni desertiche non è sempre stato lo stesso. Sembra oggi assodato che tale inaridi-mento climatico risalga solo a quale millennio fa.

Il deserto litorale si estende approssimativamente da 6°S a 27° 30’S. A nord, la corrente fredda di Hum-boldt si allontana dalla costa e la vegetazione, grazie alle piogge estive, passa da gruppi lignei xerofili alla foresta tropicale. Verso sud, la costa si trova nella zona temperata australe.

La vegetazione delle lomas

Le parti elevate della regione costiera (le lomas), situa-te a livello delle nuvole, hanno una vegetazione più ricca, denominata “oasi delle nuvole”. Tra i 500 e i 700 m - livello della garua - si può sviluppare una vegeta-zione lignea.

various coastal areas (deserts, lomas, and valleys) which is generally high, between 80 and 95%.

The climate of these desert regions has not always been as dry as it is today: it now appears certain that this extreme aridity only dates back a few millennia.

The coastal desert extends approximately from 6° S to 27° 30’ S. To the north, the cold Humboldt current moves away from the coast and, thanks to the sum-mer rains, the vegetation changes from xerophytic shrubby associations to tropical forest. Southwards, the coastline enters the southern temperate zone.

The vegetation of the lomas

The higher parts of the coastal region (the lomas), reaching up into the clouds, have a richer vegetation and are known as “cloud oases”. Between 500 and 700 m – the height of the coastal mists or garua – a woody vegetation may develop.

La vegetazione

xerofila del

Perù

8

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

Eriosyce islayensis

(f.ma bicolor)

9

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

10

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

11

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

Tra Lima e Nazca la ripartizione della vegetazione è la seguente:• da 0 a 300 m: vegetazione desertica sulla sabbia,

con Tillandsia e qualche cactacea sparsa, • da 300 a 600 m (900 m): formazione delle lomas,

grazie alle nuvole (garua), con piante erbacee o le-gnose mescolate a cactacee.Sulle colline, alle spalle della costa, si sviluppa

una vegetazione di Nostoc (cianobatteri) o di liche-ni (Cladonia). Più in alto appare una vegetazione di piante annuali con Nolana e Loasa urens, Nico-tiana paniculata,dei Chenopodium, delle Malvacee, Cariofillacee, ecc. Sulle zone rocciose si sviluppano arbusti

Between Lima and Nazca, the vegetation is subdi-vided as follows:• from 0 to 300 m: desert vegetation on sand, with

Tillandsia and some rare members of the cactus family,

• from 300 to 600 m (900 m): formation of the lo-mas thanks to the clouds (garua), with herbaceous or woody plants intermingled with cacti.On the hills behind the coast, vegetation consist-

ing of Nostoc (Cyanobacteria) or lichens (Cladonia) may grow. Higher up, the flora comprises annual plants, with Nolana and Loasa urens, Nicotiana

paniculata, some Chenopodium, some Malvaceae, Caryofillace-Eriosyce islayensis

26

un nuovo, vecchio,ibrido

Sempervivum × luisae

Sempervivum x luisae. Fon-

do Maiella, Campo di Giove

(AQ) (Monti della Maiella),

1830 m.

Sempervivum × luisae. Fon-

do Maiella, Campo di Giove

(AQ) (Maiella Mountains),

1830 m.

27

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

a new, old,

hybrid

Sempervivum × luisae

29

Ricci’s houseleek is a plant whose leaves are covered with dense glandular hairs. Already known to Tenore1, who mistook it for S. montanum, the taxon was only described in 1961 by Ignazio

Ricci under the name Sempervivum italicum; it later became S. riccii Iberite & Anzalone2 and its taxonom-ic status is still the subject of debate. Botanists take diametrically opposed views: some believe that S. ric-cii is a good species, while others hold it to be only an ecotype of the common houseleek S. tectorum. Ricci’s houseleek is exclusive to the central Appen-nines; it grows between Lazio and Abruzzo, in the area comprising the following mountains: Aurinci, Ausoni, Lepini, Simbruini, Ernici, Serralunga, Monti della Meta, Pratello, Montagne del Morrone, Maiella, Sirente, Velino, Gran Sasso, and Reatini. It may be found on flat land as well as on hillsides exposed to the south, south-east and south-west, between 700

1 Michele Tenore (1780-1861), physician, professor of botany at Naples Royal University and first Director of the Botanical Gardens. Author of numerous publications, including the monumental “Flora Napolitana” which gives the descriptions and full history of all the plants of the Kingdom of Naples known at that time, as well as the highly interesting “Cenno alla geografia fisica ed alla botanica del Regno di Napoli”.2 In describing the taxon, Ignazio Ricci did not strictly follow the rules of the Code for Botanical Nomenclature. Hence the need to rename the species.

I l semprevivo di Ricci è una pian-ta con foglie coperte da fitti peli ghiandolari. Noto già a Tenore1, che lo confuse però con S. mon-tanum, il taxon fu descritto solo nel 1961 da Ignazio Ricci con il

nome di Sempervivum italicum, divenuto, in segui-to, S. riccii Iberite & Anzalone2. La posizione tasso-nomica dell’entità è ancora oggetto di discussione. I botanici hanno opinioni diametralmente opposte. C’è chi pensa che S. riccii sia una buona specie e chi ritiene sia solo un ecotipo di S. tectorum. Il sempre-vivo di Ricci è esclusivo dell’Appennino centrale; vive tra Lazio e Abruzzo, nell’area che comprende: i monti Aurinci, Ausoni, Lepini, Simbruini ed Erni-ci, Serralunga, i Monti della Meta, Pratello, le Mon-tagne del Morrone, Maiella, Sirente, Velino, Gran Sasso, e i Reatini. Lo si incontra su terreni in piano e su pendii esposti a sud, sud-est e sud-ovest, tra i 700 ed i 2300 metri d’altitudine, tra le pietre o ad-

1 Michele Tenore (1780-1861), medico, professore di botanica della Regia Università e primo direttore dell’Orto Botanico di Napoli. Autore di numerose pubblicazioni, tra cui la monumentale “Flora Napolitana” in cui sono riportate le descrizioni e la storia completa di tutte le piante del Regno di Napoli allora conosciute, nonché di un interessantissimo “Cenno alla geografia fisica ed alla botanica del Regno di Napoli”.2 Ignazio Ricci nel descrivere il taxon non si attenne strettamente alle regole del Codice di Nomenclatura Botanica. Da qui la necessità di rinominare la specie.

Lorenzo Gallo, one of Italy’s greatest experts on Crassulaceae, recently described a hybrid houseleek, endemic to the Appenines, the result of a cross between the cobweb houseleek Sempervivum arachnoideum and Sempervivum riccii.

Lorenzo Gallo, uno dei maggiori esperti italiani di

Crassulaceae, ha descritto, poco tempo fa,

un semprevivo ibrido, endemico dei rilievi appenninici,

frutto dell’incrocio tra Sempervivum arachnoideum

e Sempervivum riccii.

Italian succulentssucculente italiche

– TAXA –

Text & Photos: Mariangela Costanzo.

S. riccii: fiori

S. riccii, flowers

30

Cactus & Co. – taxa

1

4

2

3

31

Cactus & Co. – taxa

S. riccii in diverse località; come si vede, il

taxon mostra una discreta variabilità morfo-

logica, limitata alle parti vegetative. Fig. 1 ·

Ovindoli (AQ), Velino-Sirente, 1200 m. Fig. 2 ·

Piano della Renga, Capistrello (AQ), Simbruini,

1430 m. Fig.3 · Monte Zurrone, Roccaraso

(AQ), 1620 m. Fig. 4 · Ovindoli (AQ), Velino-

Sirente, 1400 m. Fig. 5 · Forchetta Morrea,

Civita d’Antino (AQ), Serralunga, 1580 m.

S. riccii in several localities. The taxon shows

moderate morphological variability, limited

to the vegetative parts. Fig. 1 · Ovindoli (AQ)

Velino-Sirente, 1200 m. Fig. 2 · Piano della

Renga, Capistrello (AQ) Simbruini, 1430 m.

Fig. 3 · Monte Zurrone, Roccaraso (AQ), 1620

m. Fig. 4 · Ovindoli (AQ) Velino-Sirente, 1400

m. Fig. 5 · Forchetta Morrea, Civita d’Antino

(AQ) Serralunga, 1580 m.

5

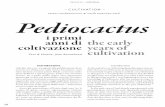

Sopra: l’esemplare

crestato di Pediocactus

nigrispinus rinvenuto

il 12 maggio 2012.

A detra: Lo stesso

esemplare, visto ‘di

spalle’.

Above: The crested

Pediocactus nigrispinus

found on May 12, 2012.

Left: The same plant,

viewed ‘from the back’.

Photos: Dixie Dringman

49

north-american cacticactus nord americani

– GLOBETROTTER –

Text: Dixie Dringman. Photos: Jay Ackerley & Dixie Dringman.

Pediocactus nigrispinus

Colockum Game Range (WA, USA)

crestatonel

inthe

Crested

Nel 1995 feci un’escursione sulla catena montuosa del Colockum Game Range, e in uno specifico sito vi trovai alcuni esemplari crestati di Pediocactus nigrispi-nus. A quanto ne sapevo si trat-

tava dell’unico ritrovamento di esemplari crestati di questa specie. Nel corso degli anni seguenti avrei vo-luto tornare in quella zona allo scopo di verificare se quelle piante esistessero ancora, ma senza un veicolo a quattro ruote motrici – che per molti anni non ebbi – l’area risultava del tutto inaccessibile. Poi un giorno sostituii il mio vecchio pickup con un GMC “Jimmy” usato, col quale potevo nuovamente avventurarmi in quelle zone impervie.

Era il momento di rintracciare quel P. nigrispinus crestato, ma il primo tentativo fallì a causa di un pon-te crollato che ovviamente mi impedì di proseguire. Nel mio secondo tentativo e nel terzo riuscii ad avvi-

During a 1995 excursion into the Colockum Game Range I found in one specific area some crested Pediocactus nigrispinus. These were to my knowledge the only crested P. nigrispinus ever report-

ed. Over the years I wanted to go back to the area and see if they were still there, but without a 4 wheel-drive vehicle, and I did not have one for many years, the location was inaccessible. I finally traded in my old blue 2 wheel-drive pickup for a used GMC “Jimmy” and was once again able to literally head for the hills.

Now it was time to relocate the crested P. nigrispi-

50

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

cinarmi di più, ma dopo tutti quegli anni non ricor-davo esattamente ove potessero trovarsi gli esemplari crestati. Un ulteriore problema era rappresentato dal fatto che non sono più così giovane come un tempo, per spostarmi lungo quei ripidi rilievi. E guidare su strade così brutte non mi pareva più così divertente come era stato un tempo.

Nel mese di aprile del 2011 Jay Akerley giunse dal-

nus, but the first attempt ended with a washed out bridge, which obviously stopped further travel. My second and third tries got me closer but after so many years I could not remember exactly where the crests were. Another problem was I am not as young as I used to be and traversing the steep ridges and driving the horrible roads just was not as much fun as I had remembered.

Photo: Jay Ackerley

51

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

la sua casa di Vancouver, B.C., Canada per parteci-pare all’annuale escursione alla ricerca di Pediocactus nigrispinus. Il clima era freddo e ventoso e le piante non erano in fiore, ma ci accordammo per restare in contatto in vista di una nuova futura opportunità. L’escursione dell’anno successivo non coincise con gli impegni lavorativi di Jay, ma in maggio riuscì a rita-gliarsi un weekend libero. Non era mai stato nel Co-

Fig. 1 · P. nigrispinus in fioritura tardiva, Maggio 2012

[con a destra Ivesia gordonii (?)]. Fig. 2 · Un esemplare

‘bianco’ trovato durante l’escursione del 2012 nel Colo-

ckum. Fig. 3 · Un altro bellissimo esemplare accestito.

Fig. 1 · A late flowering P. nigrispinus, May 2012,

[with Ivesia gordonii (?) on the right]. Fig. 2 · ‘White’

plant found in the 2012 trip to the Colockum. Fig. 3 ·

Another beautiful clump.

2

3

1

Photo: Jay Ackerley

Photo: Dixie Dringman

52

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

lockum, così decidemmo di farci un salto per vedere se riuscivamo a trovare qualche P. nigrispinus ancora in fiore, e magari, se la fortuna ci avesse assistito, indi-viduare alcune delle piante crestate.

Jay arrivò in città il venerdì sera, e partimmo la mat-tina successiva di buon’ora sapendo di avere davanti a noi una giornata piena. Dopo diverse ore di viaggio percorrendo strette strade sconnesse, giungemmo fi-nalmente a destinazione, un’area di un miglio quadra-to all’interno dei novantaduemila acri della catena del Colockum Game Range, un luogo vasto e meraviglio-so non solo per la presenza di P. nigrispinus ma anche per gli orsi, i cervi (Odocoileus hemionus), i tacchini selvatici, i fagiani e grosse mandrie di alci. Se si è for-tunati si può anche vedere una sottospecie di serpente a sonagli (Crotalus viridis) che vive in mezzo alle scure rocce basaltiche e nel folto della vegetazione lungo i torrenti; è più corto e grosso del tipico serpente a so-nagli, e di color marrone scuro.

In April 2011, Jay Akerley had taken the time to drive from his home in Vancouver B.C. to attend the annually Pediocactus nigrispinus tour. The weather was cold, windy and the P. nigrispinus were not in flower, but we did talk about “maybe next time” and agreed to stay in touch. The 2012 tour did not fit in with Jay’s work schedule, but he had a weekend in May 2012 where he could get away. He had never been in the Colockum, so we decided to take a run up and see if we could find some P. nigrispinus still in flower and if we were really lucky maybe locate one or more of the crested plants.

Jay arrived in town Friday evening and we headed out early Saturday knowing we had a full day ahead of us. After several hours of traveling on narrow, teeth jarring roads we finally arrived at our destination, a square mile area within the 92,000 acre Colockum Game Range, a vast and wonderful place, not only for P. nigrispinus, but also black bears, mule deer,

Uno dei P. nigrispinus

crestati rinvenuti nel 1995

(una seconda cresta è in corso

di formazione…).

One of the 1995 crested

P. nigrispinus (In this one a

second crest is beginning to

develop…).

Un altro esemplare

crestato nella stessa

area, nel 1995.

Another crest from the

same area in 1995.

Photos: Dixie Dringman

53

Cactus & Co. – globetrotter

Un esemplare crestato a

spine rosse trovato nel 1995.

A red spined crest from the

1995 trip.

Un P. nigrispinus ‘bianco’

crestato cresce accanto a un P.

nigrispinus normale (1995).

A ‘white’ crested P.

nigrispinus with a normal plant

growing along side (1995).

Pur basandoci sui miei ricordi di 17 anni prima, sta-vamo cercando il proverbiale ago nel pagliaio. Jay ini-ziò ad arrampicarsi sui ripidi pendii, mentre io mi limi-tai ad osservarlo dalla strada. Arriva sempre nella vita il momento in cui risulta più divertente guardare qual-cuno che si arrampica come una capra di montagna su un terreno scosceso, piuttosto che farlo di persona.

Avevamo perlustrato diversi siti, ed era ormai quasi ora di tornare, quando decidemmo di dare un’occhia-ta a un ultimo luogo che pure mi sembrava piuttosto distante dalla zona che ricordavo. Eravamo accaldati, impolverati, stanchi e affamati, e mentre stavamo tor-nando verso il veicolo, ecco che vedemmo un bell’e-semplare di P. nigrispinus crestato con spine bianche. Pensai che si potesse trattarsi di uno degli esemplari (ne ricordavo tre) originariamente da me fotografati tanto tempo prima. Eravamo entusiasti di averlo tro-vato, ma, pur cercando lì attorno ancora per più di un’ora, non ne trovammo altri. Alla fine dovemmo de-

wild turkey, pheasants and huge herds of elk. If one is lucky they might also see a subspecies of the Western rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis) that lives in the dark ba-salts and heavy undercover of the creeks; it is shorter and heavier than the typical Western rattlesnake and a dark chocolate colour.

Relying on my memories from 17 years ago, we were truly searching for the proverbial needle in the haystack. Jay worked the steep slopes while I leaned against the rig watching from the road. There does come a time in one’s life where watching someone scramble around like a mountain goat over steep and rocky terrain is more fun than doing it yourself.

We had searched several locations, and it was al-most time to head back, when we decided on one final spot that I thought was far past the area I re-membered. We were hot, dusty, tired and hungry and moving back towards the rig when there it was, a nice white-spined crested P. nigrispinus. Once we found

60

Non è facile scrivere su un argo-mento che conosco ed è cono-sciuto: immaginatevi scrivere su qualcosa che non conosco e non è conosciuto. Ci proverò ugual-mente, perché gli argomenti da

trattare sono veramente sorprendenti. Mi auguro di mettere in moto una discussione, uno

scambio di esperienze, la più ampia possibile: sono molti gli appassionati del genere Aloe nel mondo!

It’s not easy to write about some-thing you know and that is gener-ally known. So imagine what it’s like for me to write about some-thing I don’t know, and that is not known. But I’ll try all the same,

because the subjects to be dealt with are truly surpris-ing. I hope to start up as wide as possible a discussion and exchange of experiences: there are numerous en-thusiasts of the genus Aloe throughout the world!

61

variegated succulentssucculente variegate

– CULT IVAT ION –

Text & Photos: Carlo Maria Riccardi

the surprises keep on coming...

le sorprese non finiscono

mai...

The first surprise

However hard we try to cross some succulent species [the first that comes to mind is Echinopsis chamaecere-us Friedrich & Glaetzle (ex Lobivia silvestrii) (Speg.) Rowley], we never manage to get fruits with seeds, and so we are limited to reproducing them by veg-etative means, taking cuttings, that is by detaching a small piece that will easily take root.

One of the reasons for this lack of fertility is, indeed, said to be the simplicity of vegetative re-production. As I understand it, this has lead to a

La prima sorpresa

In alcune specie succulente [la prima che viene in mente è Echinopsis chamaecereus Friedrich & Glaetzle (già Lobivia silvestrii) (Speg.) Rowley], per quanto proviamo ad incrociarle tra loro, non riusciamo mai a ottenere frutti con semi e dobbiamo limitarci a ri-produrle per via vegetativa, facendone una talea, ossia staccandone un pezzetto che radicherà facilmente.

Uno dei motivi della mancanza di fertilità è stato attribuito alla semplicità di riproduzione, appunto, per via vegetativa; questo ha fatto sì, penso, che tutte le

AloeAloe maculata

62

Cactus & Co. – cultivation

Echinopsis chamaecereus presenti nelle nostre collezio-ni, derivino da una sola pianta: essendo geneticamente identiche non possono fecondarsi l’una con l’altra.

Nel vasto mondo del genere Aloe accade la stessa cosa in due tra le specie più comuni. Sono due piante di facile coltivazione, rustiche, famose per la loro esu-beranza nell’emettere polloni, che ogni collezionista di succulente, pur non amando questo genere, certa-

situation whereby all the Echinopsis chamaecereus plants in our collections derive from a single plant: being genetically identical, they cannot fertilise one another.

In the vast world of the genus Aloe, the same ap-plies to two of the commonest species. These are two easily-grown plants, hardy, famous for the exuberance with which they produce offsets, and which all succu-

63

Cactus & Co. – cultivation

mente possiede: Aloe vera (L.) Burman e Aloe macula-ta (Aloe saponaria) Allioni.

Avevo provato a ottenere dei semi da queste due pian-te, ma, dopo vari tentativi senza successo di fecondare i fiori delle A. vera in mio possesso, avevo pensato di ri-nunciare. Quest’estate però, avendo avuto la fortuna di avere in fiore nello stesso momento A. maculata e la sua cultivar ‘variegata’, non mi sono fatto sfuggire l’occasione.

1 2

3

Fig. 1 · Aloe maculata ‘variegata’ (clone di Alan

Butler). Fig. 2 · Fiori di A. maculata. Fig. 3 · Fiori di

A. maculata ‘variegata’. Sono identici a quelli di A.

maculata.

Fig. 1 · Aloe maculata ‘variegata’ (Alan Butler’s clone).

Fig. 2 · Flowers of A. maculata. Fig. 3 · Flowers of A.

maculata ‘variegata’. They are identical to those of A.

maculata.

Yucca feeanoukiaespec. nov. Hochstätter

Yucca feeanoukiae fh 1190.56 UT.

Sfondo: Habitat di Y. feeanoukiae in Utah.

Yucca feeanoukiae fh 1190.56 UT.

Background: Habitat of Y. feeanoukiae in Utah.

Una nuova specie

di Yucca (Agavaceae)

dal Nord-ovest degli

Stati Uniti

Yucca feeanoukiaespec. nov. Hochstätter

A new species of Yucca (Agavaceae) from the north-western United States

Text & Photos:Fritz Hochstätter

agavaceae of the american north-westagavacee del nord america

– TAXA–

75

Cactus & Co. – taxa

Sunto

È descritta e illustrata una nuova specie di Yucca dal Nord-ovest degli Stati Uniti, appartenente alla Sezione Chaenocarpa Engelmann, Serie Harrimaniae McKel-vey. Si tratta dell’endemica Yucca feeanoukiae, con fo-glie piano-convesse e apici fogliari finemente fibrosi.Parole chiave: Asparagaceae, Yucca, Agavaceae, Stati Uniti.

Descrizione

Yucca feeanoukiae spec. nov. Hochstätter differisce da Yucca harrimaniae subsp. sterilis (yucca sterile dello Uintah Basin) per le foglie rivolte verso il basso. Ri-zomatosa, produce molti polloni di rosette piccole e compatte. Le foglie sono piano-convesse, rivolte all’in-sù, da lisce a finemente ruvide. Il margine fogliare è fi-nemente fibroso. Le fibre, fini, sono curve e contorte.

Distribuzione

Endemica dello Utah. Distribuita su colline pianeg-gianti di roccia calcarea in aperti terreni boschivi, a un’altitudine di 2000 m., in associazione con Pedio-cactus simpsonii fh 61.8.

Tipo

Fritz Hochstätter. fh 1186.70, Nord Utah. 8 Giugno 2008. SRP. (A protezione della pianta, non si comu-nicano dettagli di località). Foglie: fh 1190.56 - Er-bario Fritz Hochstätter Semi: fh 1190.56 - Erbario Fritz Hochstätter. Materiale preso in esame: Utah: fh 1186.70, fh 1190.56. (fh = Fritz Hochstätter).

Per comparazione si è presa in esame Yucca harri-maniae subsp. sterilis Utah. Materiale esaminato: fh 1179.78, fh 1179.79, fh 1179.80, fh 1190.63.

Sezione

Chaenocarpa Engelmann, Series Harrimaniae McKelvey.

Nome comune

Yucca dalle foglie convesse e fibrose.

Ulteriori note descrittive e osservazioni

Yucca harrimaniae subsp. sterilis (yucca sterile dello Uintah Basin), menzionata nella descrizione sopra

Summary

A new species of Yucca, from the north-western Unit-ed States, is described and illustrated. It belongs to the Section Chaenocarpa Engelmann, Series Harrima-niae McKelvey. It is the endemic Yucca feeanoukiae, with flat-convex leaves and finely fibrous leaf apex.Key words: Asparagaceae, Yucca, Agavaceae, United States.

Description

Yucca feeanoukiae spec. nov. Hochstätter differs from Yucca harrimaniae subsp. sterilis (sterile yucca of the Uintah Basin) for the downward-pointing leaves. Rhizomatous, it produces numerous offsets of small compact rosettes. The leaves are flat-convex, pointing upwards, smooth to finely rough. The leaf-margin is finely fibrous. The fine fibres are curved and contorted.

Distribution

Endemic to Utah. Distributed on flattish limestone hills in open woody land, at an altitude of 2,000 m., in association with Pediocactus simpsonii fh 61.8.

Type

Fritz Hochstätter. fh 1186.70, Northern Utah. June 8th 2008. SRP. (For the plant’s protection, details of the locality are not given). Leaves: fh 1190.56 – Her-barium Fritz Hochstätter. Seeds: fh 1190.56 – Her-barium Fritz Hochstätter. Material examined: Utah: fh 1186.70, fh 1190.56. (fh = Fritz Hochstätter).

For comparison, Yucca harrimaniae subsp. sterilis Utah was examined. Material examined: fh 1179.78, fh 1179.79, fh 1179.80, fh 1190.63.

Section

Chaenocarpa Engelmann, Series Harrimaniae McK-elvey.

Common name

Convex, Twisted Fibres-Leaf Yucca.

Further notes and observations

Yucca harrimaniae subsp. sterilis (sterile yucca of the Uintah Basin), mentioned in the above description, is a rhizomatous plant that produces offsets expanding from the rhizome. Its leaves are soft, rough, pointing towards the ground. The leaf margin is barely fibrous. Its distribution comprises Duchesne Co. and Uintah Co. in Utah, on flattish sandy hills and prairies, be-

Per un confronto: Yucca harrimaniae subsp. sterilis

fh 1179.78.

For comparison: Yucca harrimaniae subsp. sterilis

fh 1179.78.

80

pianta endemica degli altipiani andini

del Sud America

Azorella compacta (Yar eta)

81

an endemic plant of the Andean plateaux in South America

Azorella compacta (Yar eta)

82

– FOCUS –

andean plants and traditionspiante e tradizioni andine

1

83

Cactus & Co. – focus

Premessa

Azorella compacta Phil. è un arbusto a forma di cu-scino che può raggiungere varie dimensioni e che si rinviene fra i 4000 e i 4800 m s.l.m. Fiorisce in pri-mavera e in estate nel freddo e in terreni umidi. È una specie che cresce in condizioni difficili sugli altopiani montani (punas) del Perù, del Cile, dell’Argentina e della Bolivia.

A. compacta, oltre ad essere una pianta particolar-mente bella, ha grande importanza dal punto di vista etnobotanico, per le proprietà e gli usi che le si attri-buiscono nell’etnomedicina, per il trattamento di dia-bete, asma, bronchiti e malattie renali, mediante infusi preparati dalle radici, dal gusto molto amaro (21), per i reumatismi e per le contusioni della pelle attraverso l’impiego della resina, come impacco (9) e come com-bustibile per la cucina e per la fusione dei minerali (27).

Premise

Azorella compacta Phil. is a cushion-forming bush that grows to variable size, which occurs between 4000 and 4800 m above sea level. Flowering in spring and summer in the cold, and in damp soils, this is a species that grows in difficult conditions on the high mountain plateaux (punas) of Peru, Chile, Argentina and Bolivia.

Apart from being a particularly attractive plant, A. compacta is of great importance from the ethnobotan-ical standpoint, for the properties and uses attributed to it in ethnomedicine: infusions of the root, which is extremely bitter, are used to treat diabetes, asthma, bronchitis and kidney diseases (21), whereas for rheu-matism and bruises the resin is used as a compress (9). The plant is also exploited as fuel, for cooking and for extracting minerals (27).

Text & Photos: F. Caceres De Baldarrago & Ignazio Poma

Pagine precedenti · In primo piano esemplare di A.

compacta; sullo sfondo l’ambiente andino Fig. 1 · A.

compacta nella località di Pampa Cañahuas, Arequipa.

Fig. 2 · A. compacta nelle falde del “Nevado Chacha-

ni”. Arequipa.

Previous pages · A. compacta in the foreground; the

Andean landscape in the background. Fig. 1 · A. com-

pacta at the locality Pampa Cañahuas, Arequipa. Fig.

2 · A. compacta on the slopes of “Nevado Chachani”,

Arequipa.

2

ISSN 1129-4299