Abruzzesi del Canada

-

Upload

abruzzo-italia -

Category

Documents

-

view

237 -

download

5

description

Transcript of Abruzzesi del Canada

2

13 Gli abruzzesi del Canada si raccontano

15 Agli abruzzesi del Canada

di Giovanni Pace

L�Abruzzo in Australia

19 The Last Best West

di Valeria De Cecco

22 Un mosaico di popoli senza conflitti

26 Gli Inuit, i Wasp e l’autorità

36 Poesie

40 Partire

48 La Union Station

49 Il Monumeto al Multiculturalismo

52 Le Italie nel mondo

di Laureano Leone

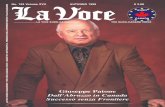

58 Un abruzzese a capo delle Giubbe Rosse

60 Un abruzzese nel governo Chrétien

62 Maggiolate Canadesi

di Ivana Fracasso

Storie di Vita66 Genitori

di Frank Jacobucci

71 Mio padre? un uomo “incredibile”

di Ivana Petricone

78 Il figlio senatore

79 Maria Vincenza Di Nino

Una ragazza di 86 anni

di Adriana Suppa

83 In Canada

di Odoardo di Santo

88 “Tu vuoi fare l’italiano, ma sei nato...”

di Roberto Martella

93 Nonno, nonna, il camion rosso e il blu

di Davide D’ Alessandro

97 Emigranti degli anni 90

di Paola Chiarini

100 “I paesani ci prestarono i soldi per la casa”

di Angelo Delfino

Sommario

3

SPECIALE

CANADA

Storie di Vita104 Pioggia e leva mi hanno portato

in Canada - di Nivo Angelone

108 Silvano Tancredi

111 Gino Ventresca

113 Franco Ventresca

114 Maria Deli

117 Autobus pieni di giovani

partivano verso l’ignoto

di Maria Morgani

120 Gabriele De Luca

124 Alberto Mammarella

127 Fausto Di Berardino

132 Cesidio Nucci

134 Italo Rosati

139 Antonio Di Tommaso

Scuola e Scienza140 Il Centro Scuola e Cultura Italiana

141 Alberto Di Giovanni

144 Panfilo Corvetti

145 Canadian Colle Italy

The Renaissance School

148 Gerardo De Iuliis

Abruzzo Business151 Una vetrina internazionale

Il ruolo strategico del Canada

di Vito Domenici

154 L’Abruzzo in mostra all’estero:

il calendario delle fiere

156 Il Nafta

157 Il Canada nel Web

158 Canada: i numeri

Import & export

Indirizzi160 Le associazioni

Anno VI numero 1 2002

Questo numero é dedicato alla

comunità abruzzese del

Canada, e in particolare a quella di

Toronto. Abbiamo deciso di iniziare da qui

il nostro cammino perché con i suoi

80.000 abitanti di origine abruzzese

Toronto é la città più "abruzzese" del

mondo. La seconda città abruzzese dopo

Pescara. Una città dove si parla italiano

quasi dovunque e dove, come raccontano

alcune delle testimonianze raccolte, si

può vivere tutta una vita senza aver biso-

gno di imparare l'inglese. A presentarcela

sono più voci che in prima persona hanno

accettato di raccontarci la loro vita e la

storia di questo giovane paese. Una

nazione che hanno contribuito a costruire

prima con il sudore della fronte, poi con la

loro intelligenza e creatività. Siamo grati a

tutti loro per il dono che ci hanno fatto, per

la fiducia e il calore con cui hanno accolto

il nostro invito, per il tempo che ci hanno

dedicato. Un grazie di cuore a tutti, anche

da parte dei nostri lettori.

L'editore

This issue is dedicated to the

Abruzzese community in Canada,

with particular emphasis on the community

in Toronto. We have decided to begin our

tale with them because with its more than

80,000 citizens of Abruzzese origin,

Toronto is the largest “Abruzzese city”

abroad, second only to Pescara. It is a city

where Italian is spoken almost everywhere

and where, as some of the people inter-

viewed have told us, one can still live one’s

whole life without learning English. There

are many voices, all willing to talk to us of

their experiences in this young country. It

is a country which they helped to build, first

with the sweat of their brows, and now with

their intelligence and creativity.We thank

all of them for the gift they have given us,

for the trust and warmth with which they

acceded to our request and for the time

that they committed to allowing us to talk to

them. We thank them from the bottom of

our hearts, and on behalf of all our readers

as well.

The Publisher

Gli abruzzesi del Canada si raccontano

Dalla Federazione Abruzzese di Toronto

Anome della Federazione di Toronto sono lieta di dirvi quanto apprezziamola vostra rivista Abruzzo Italia. La rivista è importante per tutti noi che

abbiamo lasciato le belle colline dell'Abruzzo. Ci dà la possibilità di tenerci incontatto con coloro che sono rimasti in Abruzzo e anche con chi l'ha lasciatoper recarsi in altre parti del mondo e con cui abbiamo le tradizioni e i sentimen-ti della nostra regione in comune. Sono molto fiera di rappresentare laFederazione come presidente. Con stima.

On behalf of the "Federazione di Toronto" I am pleased to extend our

appreciation of your magazine Abruzzo Italia. Your magazine is important

to all of us thet have left the beautiful hills of Abruzzo. It is giving us the oppo-

tunity to keep in touch with the people who remain today in the region of Abruzzo

as well as those who have left the region for other parts of the world that share

our traditions and feelings towards our regione. I am very proud to represent the

Federazione as president. Yours truly,

Maria MorganiPresidente della Federazione delle Associazioni Abruzzesi di Toronto

The Abruzzesi of Canada Tell Their Own Stories

T H E L A S T

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

6

Testo di Valeria De CeccoFoto antiche tratte da archivi privati

e dall’archivio della Multicultural History Society of Ontario, Toronto

B E S T W E S T

7

Quasi 4 milioni di abitanti(con le città satelliti di Vaughan,Mississauga, Richmond Hill etc.),400.000 italiani, 80.000 abruzzesi.Toronto é la seconda città abruzzesedopo Pescara, la più grande del Canada.

La prua della Constitutiondurante una tempesta sull’Atlanticoai primi di marzo del 1957. La foto éstata scattata da Eustachio Presutto.

TORONTO

Avvicinandosi dal cielo,

in inverno, dopo ore di volo sul "Mare

dell'Oscurità", l'Oceano Atlantico, il

Canada appare come un bagliore dall'ac-

qua. La distesa ghiacciata del San

Lorenzo e infiniti chilometri di neve tutto

intorno. L'aereo sorvola Montréal e poi

scende piano verso la piatta scacchiera di

Toronto. Un brulichio di luci a 360 gradi

fino all'orizzonte, spaccato al centro dal

fiume luminoso delle auto che percorrono

i 300 chilometri di Yonge street, dalla riva

del lago Ontario fino alla Georgian Bay, la

strada di città più lunga del mondo, dico-

no, la strada che divide Toronto a metà: da

un lato l'est, dall'altro l'ovest.

Una città abruzzeseQuasi 4 milioni di abitanti

(con le città satelliti di Vaughan,

Mississauga, Richmond Hill etc.),

400.000 italiani, 80.000 abruzze-

si. Toronto é la seconda città

abruzzese dopo Pescara, la più

grande del Canada. Le sue fon-

damenta, i suoi grattacieli, le sue

strade, hanno dato lavoro a un

paio di generazioni di italiani tra la

fine degli anni 50 e i 70. Nel 1971

arrivò qui anche Flaiano per gira-

re il suo "Oceano Canada". In

quegli anni la città cresceva "di

quarantamila appartamenti ogni

anno". E si avviava a diventare "il

cuore di una megalopoli che si

stenderà nel relativo deserto che

ora la circonda. In questo futuro

enorme agglomerato urbano dei

grandi laghi", ci raccontava

Flaiano, "gli statistici prevedono

che nel 2000 potranno vivere cin-

quanta milioni di abitanti".

8

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

Il quartieredegli

immigratisu Edward

Streetnel

St.John’SWard

a Torontoin una foto

del 1918

Operai italiani scavano le fognature dellacittà di Toronto. E’ il 12 febbraio 1912

9

The Last Best WestApproaching it from the sky in win-

ter, after hours of flying over the

“Sea of Darkness”, the Atlantic Ocean,

Canada looks like a bright glow emer-

ging out of the water, with frozen

expanse of the St. Lawrence and infini-

te acres of snow on all sides. The air-

plane flies over Montreal and then

begins its slow descent towards the flat

checkerboard of Toronto. All around as

far as the eye can see are shimmering

lights, sliced down the middle by a

luminous river of cars bustling along

Yonge Street which, from the shores of

Lake Ontario, proceeds uninterrupted

to Georgian Bay and beyond, the lon-

gest street in the world, it is said, the

street that splits Toronto in two, into

east and west.

A City of AbruzzesiSome four million people live here (if

one includes the satellite cities of

Vaughan, Mississauga, Richmond Hill,

etc), 400,000 Italians, 80,000 Abruzzesi.

Toronto contains the second largest

Abruzzese community of any city in the

world, next to Pescara. It is Canada’s

largest city. Its foundations, its skyscra-

pers, its roads, have provided work for

several generations of Italians between

the end of the Second World War and

the seventies.

In 1971 Flaiano came here to shoot his

“Ocean Canada”. In those years the city

was growing at a rate of “forty thousand

apartments annually”. And it was on its

way towards becoming “the heart of a

megalopolis that would expand outwards

into the relative desert which now sur-

rounds it. In this enormous future urban

agglomeration of the Great Lakes,”

Flaiano told us, “statisticians predict that

by the year 2000 as many as fifty million

people could be living here”.

Toronto Street nel 1912.Operai italiani al lavoro sulle rotaie del tram. Alla fine dell’800 il Canada erapubblicizzato dai suoi governanti bisognosi di sudditi come “The Last BestWest, l’ultimo miglior posto dell’occidente.

10

Il balcone sugli UsaMa gli statistici non sempre hanno ragione. Tutto il Canada oggi,

conta appena 30 milioni di abitanti concentrati soprattutto lungo il trac-

ciato della "401", l'autostrada che corre fra Halifax e Vancouver a

pochi chilometri dal confine con gli States. I canadesi dicono che

sono come affacciati a un balcone sugli Stati Uniti. Il gigante che

incombe alla porta di casa. Tanti abruzzesi sono passati di là

prima di trovare pace e fortuna a Toronto. Altri sono arrivati in

cerca di migliore destino da Argentina e Venezuela, Brasile e

Belgio. Così é facile, facilissimo trovare qui pezzi di famiglie

che hanno lasciato zii, fratelli e cugini in qualche altro angolo

del mondo.

Nel 1800, quando gli Stati Uniti ospitavano già più di 5 milioni dipersone, nel territorio canadese, il secondo paese più esteso

del mondo (il primo é la Russia) c'erano appena 580.000 abitanti traindigeni (inuit e indiani) e coloni. L'attuale popolazione é quindiquasi tutta costituita da immigrati da altre nazioni arrivati in tempirelativamente recenti, ossia dalla fine dell'800 ai giorni nostri. Il risul-tato é un "mosaico" di razze e culture che, a differenza del "meltingpot", il "crogiolo" in cui gli Stati Uniti hanno fuso tutte le nazionalità,qui é riuscito a sopravvivere grazie all'assenza di grandi conflitti.Perfino la popolazione dei nativi é rimasta stabile nei secoli.L'abilità nella caccia in un territorio inaccessibile agli europei (ininverno nel sud si sfiorano i 40 sotto zero) e il commercio dellepelli li hanno salvati dalle stragi che hanno insanguinato gliStates.

Un mosaico di popoli senza conflitti

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

The Ward, il quartiere degli immigrati in una fotoscattata nel primo decennio del ‘900

11

A Balcony Overlooking the U. S. A.But the number crunchers don’t always get it

right. Today all of Canada has a population

of barely 30 million concentrated largely

along the swathe cut by Highway 401 which

stretches from Halifax to Vancouver and lies

only a few kilometres north of the border with

the United States. Canadians say it’s as if

they were looking over a

balcony into the United

States. The giant looms on

their doorstep. Many from

Abruzzo passed through

the U. S. before finding

peace and fortune in

Toronto. Other arrived

looking for a better future

from Argentina, Venezuela,

Brazil, Belgium. So it’s

very easy here to find fami-

lies who have left behind

uncles, brothers or cousins

in some other corner of the

world .

In 1800, when the United States had more than 5 million peo-ple, in Canada, today the second largest country in the world

next to the Russian Federation, there were barely six hundredthousand souls. between the natives (Inuit and Indians) and thecolonists. Its population today, then, is consists almost entirelyof immigrants who arrived relatively recently, that is from theearly eighteen hundreds on. The result is a “mosaic” of peoplesand cultures rather than a “melting pot” which the United Statesclaims it has produced. In Canada this was largely make pos-sible because there were no great conflicts among the diverse

groups. Even the native population has remained by and largestable over the centuries. Their hunting and scouting skills in anenvironment hostile to Europeans (even in the south temperatureswill dip to minus 40 Celsius) and their indispensable help in the fur

trade spared them the slaughter which bloodied the United States.

Tanti abruzzesi sono arrivati a Toronto da altre nazioni. A sinistra: Eustachio Presutto inBelgio nel 1954 prima di trasferirsi in Canada. Al centro: Lucia Novellicon le figlie Nicoletta e Marietta.Qui sotto: negozi nel quartiere italiano di Toronto. Foto scattata nelprimo decennio del ‘900.

A Mosaic of Peoples without Conflicts

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

12

L'ultimo WestCome accadde ai primi esploratori, che

sconsigliarono ai loro re di colonizzare

queste terre, del tutto prive di seta e spe-

zie, anche chi cercava una vita migliore

difficilmente pensava al Canada, gelato

per sei mesi all'anno, e preferiva partire

per altri lidi più promettenti. Soltanto la

crisi dei paesi sudamericani ed europei e

la chiusura dell'immigrazione negli Stati

Uniti fece riscoprire alla metà del 900,

quello che alla fine dell'800 era pubbliciz-

zato dai suoi governanti bisognosi di sud-

diti, come "the Last Best West", l'ultimo

miglior posto dell'occidente. All'epoca c'e-

rano appena 5 milioni di abitanti e molti

chilometri di strade e ferrovie da costruire,

miniere da sfruttare, boschi da tagliare,

fabbriche da far funzionare.

13

Abruzzesi. “I tre moschettieri”:Gabriele De Luca, Raffaele Barone e Giuseppe Smargiasso di Lanciano da poco arrivati in Canada nel 1960. A sinistra: operai italianial lavoro in un cantiere delle ferrovie. Nella prima metà del ‘900 in tutto il Canada c’erano appena cinque milioni di abitanti.

The Last FrontierAs happened with the first explorers who

discouraged their sovereigns from coloni-

zing these lands which were totally

lacking in spices and silk, those who were

in search of a better life rarely thought first

of Canada, frozen as it is for a good six

months of the year. They preferred to

seek out sunnier climes. Only the crisis in

South American countries and in Europe

along with the tightening of immigration

policies in the United States led to the

rediscovery by the waves of immigrants in

the fifties what had been touted as “The

Last Best West” at the end of the nine-

teenth century by government pamphle-

teers anxious to find subjects to make its

working population grow. At the time

there were only some 5 million people in

Canada and thousands of kilometres of

roads and railways lines to build, mines to

dig out, forests to chop down and facto-

ries to be kept going.

Esercitazione sulla nave Vulcania nel 1962, al centro con il berretto AntonioDi Tommaso, di Caldari, Ortona. Sotto: gruppo di lavoratori italiani nel 1915.

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

14

Il Mosaico di TrudeauOggi a Toronto ci sono più di 40 associa-

zioni abruzzesi che coltivano gli usi e

costumi natii accanto ad altre 60 diverse

comunità nazionali. Un "mosaico" di cultu-

re unico sulla terra, che gli é valsa la

palma dell'Unesco come "città etnicamen-

te più diversificata del mondo". Il termine

"multiculturalismo" é stato coniato qui nel

corso degli anni 70 per definire la politica

del primo ministro Pier Elliot Trudeau e

dal 1982 la nuova costituzione garantisce

e valorizza la libertà di culto, di lingua, di

istruzione e di stampa a tutte le etnie.

Così accendendo un televisore o una

radio si possono ascoltare circa 40 lin-

guaggi diversi (gli altri venti non hanno

media) che, volendo, si possono

approfondire sui giornali, oppure a tavola

nei ristoranti etnici, o facendo shopping

dai giamaicani a Bathurst, dai greci a

Danforth, dai cinesi a Dundas Street...

Una curiosità: una leggendametropolitana dice che la lingua

degli inuit dell'Artico ha oltre centotermini per definire la neve e nessu-no per indicare la figura del capo,era il gruppo a detenere l'autorità.Ironia della storia: i canadesi sonooggi famosi per il loro rispetto versol'autorità, un atteggiamento descrit-to perfino nelle guide turistiche eche a Toronto trova la sua massimaespressione. Ancora oggi, peresempio, i Wasp della città provanoun certo imbarazzo per la ribellionedi William Lyon Mackenzie, focosoeditore di un quotidiano locale, chenel 1837 in una taverna di YongeStreet dove si serviva soprattuttowhisky, incitò qualche centinaio diavventori alla rivolta control'Inghilterra.

Una leggenda metropolitana

Gli Inuit, i wasp e l'autorità

In alto: processione a Toronto.Gli italiani hanno continuato a onorare i propri santi secondo i riti tradizionalianche oltreoceano .

15

Trudeau’s MosaicToday there are more than 40 Abruzzese

associations which keep alive their

customs and traditions alongside ethnic

groups from over sixty other countries. A

“cultural mosaic” unique among the

nations of the world which has gained it

praise from UNESCO as “the most ethni-

cally diverse city on the globe.” The term

“multiculturalism” was coined here in the

seventies to characterize the policies of

Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau and

as of 1982 the Constitution has guaran-

teed and strengthened freedom of reli-

gion, language, education and press for

all ethnic groups. When one turns on the

radio or television, one can hear over forty

languages being used (not all ethnic grou-

ps have media in their languages). One

can also experience other languages in

newspapers, in restaurants or by going

shopping, for example in the Jamaican

district around Bathurst and Bloor, in the

Greek areas on the Danforth and in

Chinatown along Dundas and Bay.

An interesting "fact" whichhas since been shown to be

an urban legend, says that the lan-guage of the Inuit or the Eskimohas more than a hundred differentterms for describing snow andnone for designating the chief orperson in charge, since authorityis vested in the collective orgroup. And ironically it wouldseem, one of the things Canadiansare known for is their immenserespect for authority: even touristguides point this out. In fact, eventoday there is a bit of embaras-sment in some quarters at therebellion of WIlliam LyonMackenzie, a fiery editor of a localpaper who in 1837, on a tavern onYonge Street (now the centre ofToronto) where the principal beve-rage was whisky, incited about ahundred patrons or so to rebelagainst the British crown.

An Urban Legend

The Inuit, the Waspsand Authority

Le signore hanno portato inCanada le ricette e gli attrezzi dellacucina regionale italiana. Nella fotodel 1961: Lucia Presutto

Dicembre 1931. Banchetto in onore delprofessor Emilio Goggio

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

16

Media e "mammasantissima"L'icona del multiculturalismo mediatico di Toronto

é un italiano: Johnny Lombardi, proprietario della

Chin Multicultural Radio International, la stazione

che per tutto il giorno trasmette in decine di lingue

diverse. Johnny fu intervistato da Flaiano. Una volta

a settimana parlano attraverso la Chin e la voce di

Ivana Fracasso anche gli abruzzesi di Toronto. Il

programma si chiama "L'Eco d'Abruzzo" ed é nato

nel 1995 grazie all'impegno di Gino Ventresca,

Odoardo Di Santo ed Eligio Paris, tre nomi che figu-

rano nell'albo d'oro della comunità. Imprenditori il

primo e il terzo, politico il secondo, fanno parte di

17

Media and the “Big Bosses”Toronto’s icon of multiculturalism in the media is an

Italian, Johnny Lombardi, the owner of Chin

Multicultural Radio International, the station which

broadcasts in a host different of languages every day.

Johnny was interviewed by Flaiano back then. The

Abruzzesi in Toronto also get their own half hour pro-

gram every week. L’eco d’Abruzzo is moderated by

Ivana Fracasso and was the brainchild of Gino

Ventresca, Odoardo Di Santo and Eligio Paris, three

prominent names in the community. The first and third

are businessmen and the second a journalist and poli-

tician and they are all part of group who for years have

Bloor Street al tramonto.Nel secondo dopoguerra

in questa zona di Torontosi era stabilita la maggior

parte degli italiani.Nella pagina accanto:

Johnny Lombardi proprietario della Chin

Multicultural RadioInternational, la stazioneche trasmette in decine

di lingue diverse

appeared in the same list of names of

those who are looked up to by the com-

munity and who figure year after year at

the head tables of major events. They are

people who “have done a great deal for

the community” alongside the so-called

“Big Bosses” who have made their own

fortunes on the same community. The

Abruzzesi of Toronto, say Italian politi-

cians, have never been able to tell the two

apart and, often, prefer the latter.

Little Italy“The Exciting City” is in essence an agglo-

meration of large provincial towns, where

everyone knows each other and the

various ethnic groups more or less recon-

stitute among themselves what they left

behind in their lands of origin. The Italians

started out along College Street, in the

southern part of the city not too far from

Lake Ontario and gradually moved north,

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

18

quella che é la classe dirigente degli

abruzzesi di Toronto. Una categoria nella

categoria che da anni elenca gli stessi

nomi nella lista del rispetto popolare e

vede gli stessi volti ai tavoli delle grandi

occasioni. Personaggi che "hanno fatto

del bene alla comunità" accanto a "mam-

masantissima" che sulla stessa gente

hanno costruito solo le proprie fortune. Gli

Tony Valeri, fondatore della Camera di Commercio Italiana di Toronto,e la moglie Concetta. In alto a sinistra: Eligio Paris uno degli ideatori del programma l’Eco d’Abruzzo.

19

to St. Clair Avenue West, Eglinton

and Lawrence. The northward exo-

dus kept pace with their bank accounts.

There are street signs which still recall the

past: part of College Street is designated

as Little Italy

and a section

of St. Clair has

been named

Corso Italia.

But what has

remained is

mostly stores

with red white

and green in

their signs.

The Italians

have to a large

extent moved

even further

north, to

Woodbridge,

once a solid

Anglo-Saxon

c o m m u n i t y.

Here one finds

thousands of wood and brick houses, with

manicured lawns replete with petunias

and lilac trees during the summer. In the

stores you’ll find Pugliese bread, Italian

periodicals, Juventus and Inter pennants

and real espresso coffee in the “bars”.

Italian is the language of every day life.

abruzzesi di Toronto dicono che i politici

italiani non hanno saputo mai distinguere

gli uni dagli altri e, spesso, prediligono i

secondi.

Little Italy"The Exciting City", la Città Eccitante, alla

fine é un insieme di paesoni di provincia,

dove tutti si conoscono e i vari gruppi etni-

ci riproducono nel proprio quartiere ciò

che hanno lasciato in patria. Gli italiani

hanno cominciato da College Street, a

sud della città, poi si sono spostati a Saint

Clair Avenue West, Eglinton, Lawrence.

Un'avanzata verso nord di pari passo con

la crescita del loro conto in banca. La

segnaletica stradale indica ancora

College Street come la Piccola Italia e

parte di Saint Clair come Corso Italia, ma

qui sono rimasti soltanto i negozi con le

insegne tricolori. Gli italiani, per lo più si

sono spostati a Woodbridge, a nord della

città strappando questa zona agli anglos-

sassoni. Migliaia di villette di legno e mat-

toncini rossi, prati perfettamente rasati, in

estate petunie e lillà dovunque. Nei nego-

zi pane pugliese, riviste italiane, gagliar-

detti della Juventus o dell'Inter, vero caffé

L’Eco d’Abruzzo. é la trasmissioneradiofonica che parla dell’Abruzzoai torontini. Nella foto: la conduttrice Ivana Fracasso insieme a Gino Ventresca,uno degli ideatori del programma,e a Cesarino Bomba, di Lanciano,ospite in visita a Toronto

Italiani. Ogni momento é buono peresibire il tricolore. A destra unacoppia abruzzese con le magliettedella Nazionale di calcio.

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

20

espresso nei bar. Lingua ufficiale l'i-

taliano. Non ci si accorge nemmeno

di essere dall'al-

tra parte

dell'Atlantico.

Wasp e WopChi "ha fatto

molto successo",

invece, preferi-

sce stare lontano

dal "paese", nelle

villone con pisci-

na nascoste fra

gli aceri di

Richmond Hill,

nei grattacieli di

cristallo in riva

all'Ontario, nel

bosco cittadino di

Forest Hill dove

ogni residenza é

un gioiello di

You might not even notice that you’-

re on the other side of the Atlantic.

Wasp and WopThose “who have made it”,

however, prefer to stay away

from the “town”. They have

mansions with pools enscon-

ced amidst the maples of

Richmond Hill, in the crystal

palaces along the shore of

Lake Ontario or in the wooded

area of Forest Hill in the heart

of the city, where each home is

a unique piece of architecture

reflecting the turn of the cen-

tury Victorian or Georgian sty-

les. Within these neigh-

bourhoods and these confines

one sees the living contradic-

tion of the most multicultural

city in the world: over 60 well-

represented ethnic groups

La festa per la Coppa del Mondo all’Italia nel 1982, nel centro di Toronto. Tuttilo ricordano come un momento di riscossa degli immigrati italiani in Canada.

21

architettura stile vecchia Inghilterra.

In questi quartieri si consuma la con-

traddizione della città più multicultu-

rale del mondo: più di 60 etnie e il control-

lo del potere a un gruppo di appena 2.000

anime, per l'80 per cento WASP, ossia

anglossani, protestanti e di razza bianca.

Non una donna, né un nativo fra i 2.000. In

compenso il monopolio dello stile é salda-

mente in mano agli ex Wop, With Out

Papers, i "senza documenti", che dopo

aver costruito i grattacieli di Down Town, lo

Sky Dome, stadio con il tetto che si apre, e

la CN Tower, la più alta del mondo con i

suoi 550 metri, oggi sono i sacerdoti

dell'Italian Way of Life. E gli abruzzesi in

questo campo non hanno rivali. Soprattutto

a tavola.

Il potere a tavolaRoberto Martella, di Atri, ha cominciato a

servire pasta alla chitarra in un piccolo

locale in Yonge Street. Qualche anno fa ha

with the bulk of the power held by

some 2000 individuals, most of

which (some 80%) are WASPs

(Anglo-Saxon, White, Protestant), not one

woman or native among them. On the

other hand, the monopoly on style is

firmly in the hands of the ex-Wops (With

Out Papers), who, having built the down-

town skyscrapers, Sky Dome (the

Stadium with a retractable rood), the CN

Tower (the tallest free-standing structure

in the world rising 550 metres into the sky-

line), today are the high priests of the

Italian Way of Life. And the Abruzzesi are

second to none in this field, especially

where food is concerned.

Food and PowerRoberto Martella, from Atri, began serving

pasta “alla chitarra” in a little place on

Yonge Street. A few years ago he bought

the whole building and turned the entire

first floor into a sanctuary of Italian cultu-

Casa Abruzzo. Gli abruzzesi di Toronto hanno costruito un grande complesso con appartementi per anziani e l’hanno intitolato alla propriaregione. In basso, nella pagina accanto: Fausto Di Berardino, proprietariodel ristorante Coppi, luogo di ritrovo preferito da finanzieri e top manager.

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

22

comprato tutta la palazzina trasforman-

do il piano terra in un santuario della

cultura italiana. Non solo cibo, ma anche

libri, musica, oggetti, immagini di arte e

vita italiana. "Grano" é diventato il punto

d'incontro dell'intellighenzia di Toronto. Ai

tavoli di "Coppi", invece, sotto le giganto-

grafie del grande campione, Fausto Di

Berardino di San Vito, nutre finanzieri e top

manager con risotto servito nelle forme di

parmigiano e pesce al sale. E ancora

un'abruzzese, Elisa Camarra di Popoli, ha

insegnato ai torontini a mangiare la pizza.

Camarra's, é stata la seconda pizzeria

aperta qui nel 1958. Oggi che la città ne

conta 1.300, serve ancora la migliore

"napoletana" di Toronto.

re. Not only food, but books, music,

objects and images of Italian art and

life. His restaurant, “Grano”, has beco-

me the meeting place of Toronto’s intelli-

gentsia. At “Coppi”, on the other hand,

under the gaze of the giant photos of

Fausto Coppi, the cycling champion of

Italy during the fifties, Faustino Di

Berardino from San Vito, its owner, pro-

vides financiers and top managers the

culinary experience of their lives on a

daily basis (closed on Sundays) with his

risotto served in parmigiano containers

and salt baked fish. Another Abruzzese,

Elisa Camarra from Popoli, taught

Torontonians what it means to eat good

pizza. In 1958 Camarra’s was the

second pizzeria to open in Toronto.

Today, with over thirteen hundred pizza

establishments, she still serves the best

Neapolitan pizza in the city.

Gli ambasciatori della cucina italiana. A sinistra: Roberto Martella, titolaredel ristorante Grano, punto di incontro dell’intellighenzia torontina. A destra:Elisa Camarra, che nel 1958 ha aperto la seconda pizzeria di Toronto. Oggiche ce ne sono 1.300, serve sempre la migliore napoletana della città.

Questo articolo é stato pubblicatosu “Il Centro”, quotidianodell’Abruzzo, il 5 agosto 2001

23

Il direttivo della Federazione degli Abruzzesi di Toronto.Da sinistra: Ennio Michelucci, Emidio Ventresca (tesoriere), Emidio Cicconi,Luisa Di Carlo, John Di Nino (2° vice presidente), Maria Bianchi (segret aria),Maria Morgani (presidente), Tonino Centofanti, Davide D’Ercole (1° vicePresidente) e Antonio Di Fiore. Nella foto manca il consigliere GianniMontanaro. La Federazione di Toronto é stata fondata il 4 ottobre del 1989 daArt La Caprara (presidente), Merino Antonucci (1° vice presidente), Donato DiBenedetto (2° vice presidente), Gabriele De Luca (tesoriere), Gino Di Persio(segretario), Archimede Altoro e Fulvio Florio.

�The Leaders in Automotive Parts�

4000 Steeles Ave. W. Unit#7-8 Woodbridge13 Melanie Drive Brampton101 Healey Road Bolton

Tel. (905) 791-5256Fax (905) 857-8100

www.albatrossauto.com

Alberto MammarellaPresident

8611 JANE ST.

CONCORD, ONTARIO, CANADA L4K 2M6

TEL. (416) 665-7337 • FAX (905) 660-0938

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

24

Nel mio giardino

Io ho una casa adesso.

Mio padre seminava i suoi semi

nel suo giardino

e ne raccoglieva lattuga e pomodori.

Aveva capito chi fosse quando

le sue mani formavano il formaggio

tratto dal latte del suo gregge

Arrivato qui, ne fu meno sicuro

e lavorava in fabbriche o cantieri.

Faceva il suo vino

e continuava a sacrificare l'agnello pasquale per noi

(e anche per sé, certo).

Amava ciò che era suo con poco sfoggio

e con ancora meno parole.

La lingua non si piegò mai a lui, nonostante la sua forza.

Gli ho scritto i numeri su un foglio

in modo che potesse compilare gli assegni,

pagare i conti...

La mia giovinezza è stata un continuo vergognarmi di lui.

Il mio piccolo volto arrossiva, distoglievo lo sguardo

nelle riunioni scolastiche quando veniva timidamente

con incerta sintassi a chiedere di me.

Nel mio giardino

ho il mio prato e i miei fiori

e gli ortaggi li compero da Dominion.

Distolgo lo sguardo ora per la vergogna

di essere mai stato quel ragazzo.

(Traduzione dall’inglese di Giuliano Di Tanna)

In my backyard

I own a house now.

My father sowed his seeds

in his backyard,

and reaped the lettuce and tomatoes.

He had known who he was when

his hands formed the cheese

drawn from the milk of his flock.

Having come here, he was less sure

and worked in factories or construction sites.

He made his own wine and slaughtered still

the Easter Lamb for us

(and for himself too, there's no denying).

He loved what was his own with little show

and fewer words.

The language never yielded to him, strong as he was.

I wrote the numbers out on a sheet

so he could write his cheques,

pay his bills...

My youth was spent in shame of him.

My tiny face would blush, my eyes avert

on parents’ night when he would timid come

to ask in broken syntax after me.

In my backyard

I have my grass and flowers

and buy my produce at Dominion.

My eyes avert in shame now

that I ever was that boy.

La famiglia De Iuliis. Celestino De Iuliis, dabambino, insieme ai genitori, Maria e Italodurante una gita a Niagara Falls.

25

Chi é l'autore di queste poesie

L'autore di queste poesie é CelestinoDe Iuliis, originario di Campotosto,

arrivato in Canada a sei anni nel 1953con sua madre, Maria Deli. Le due poesieche pubblichiamo sono tratte dal suolibro "Love’s Sinning Song and OtherPoems" (Il canto peccaminoso dell’amoreed altre poesie) e sono entrambe dedica-te a suo padre Italo, prematuramentescomparso all'età di 60 anni. ACampotosto faceva il pastore, in Canadalavorò per 25 anni nei cantieri, nelle fabri-che e, infine, in un negozio di ferramentapoiché la sua salute non gli permettevapiù di fare lavori pesanti. E' stato forselui, più di tutti, a lasciare nel figlio unprofondo senso di amore e di rispetto perl’Italia e l’Abruzzo e, soprattutto, per ilsuo paese, Campotosto, di cui ad ognifesta, ad ogni cena, ad ogni raduno parla-va con nostalgia e con tenerezza, ma chenon ha mai più rivisto. Infatti lo incorag-giava, fin da bambino a copiare e leggerebrani in italiano da un vecchio sillabarioche si era procurato, chissà dove. Ma sipuò immaginare con quanta poca vogliae altrettanta scarsa comprensioneCelestino rispondesse a queste sollecita-zioni. Infatti, dopo il normale corso di tudiin inglese, l’italiano lo ha recuperato sol-tanto all’università e facendo l’attore eregista nella filodrammatica laCompagnia dei giovani, con cui ha allesti-to pezzi teatrali di Pirandello, Machiavelli,Goldoni, Dario Fo ed altri. Oggi vive consua madre e uno dei suoi figli, Marco.L’altro figlio, Frederic, vive con la madre,ma si vedono tutti molto spesso. Insegnamatematica al George Brown College, fal'assicuratore e traduce dall’italiano ininglese (oltre a curare l'edizione inglesedi Abruzzo-Italia, ha tradotto diversi libri esta lavorando a una nuova traduzione ininglese in terza rima dell’Inferno dellaDivina Commedia).

L'orto in giardino

In Canada quasi tutti gli immigranti

appena hanno potuto si sono comprati

una casa loro. Il che vuol dire una villet-

ta da uno a tre piani. Ogni casa ha un

pezzetto di terra, sia davanti che di die-

tro. Gli anglosassoni, per lo più pianta-

vano e continuano a piantare fiori intor-

no ed erba nel mezzo nel giardinetto

dietro casa, detto Back Yard. Gli immi-

granti, tra cui gli italiani, per lo più hanno

eliminato erba e fiori per piantarci podo-

modori, lattuga, sedano, fagioli ecc., tra-

sformando i giardini in orti. "Dominion" é

un grande supermercato.

Flowers or Vegetables

in Your Garden

In Canada almost all immigrants, as

soon as they were able, purchased a

home of their own. This usually meant a

single, one to three storey house, even

in the large cities. In Italy, most people

who live in cities live in apartments,

which they may rent, but more often

own. So they don’t have front of back

yards as is the case with almost all hou-

ses in Canada. Anglo-Saxons, immi-

grants of earlier generations in most of

Canada, as a rule, plant grass and

flowers in their back yards. With few

exceptions, more recent immigrants,

including Italians or course, have tended

to remove grass and flowers and plant

tomatoes, lettuce, celery, beans, and so

forth, turning their backyards from flower

beds into vegetable gardens.

“Dominion” is a large, Canadian super-

market chain.

Celestino

De Iuliis

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

26

The Bells

of Campotosto

Campotosto is at 1450 m above

sea level. Winters there are long.

In former years one had to stock

one’s larder with care in order to sur-

vive the six months of winter when

outdoor activities came to a standstill,

what with all the snow and the bitter

cold.. The stories told around the

supper table, at weddings and holi-

day meals of improvident or poor

families that went hungry over the

winter are legion. Italo De Iuliis, to

whom this poem is dedicated, never

went back to Campotosto after lea-

ving it in 1952 to find a better life in

Canada. He is buried in Toronto. But

the bells of Campotosto remembered

him, ringing the “death knell” for him,

as they do for all those born there

who leave this world, no matter where

they may have been living, and wel-

comed his spirit back among his hills.

In English, of course, bells say “ding

dong”.

Who Is the Authorof These Poems

These poems were written by CelestinoDe Iuliis who was born in Campotosto

and arrived in Canada at the age of six in1953 with his mother Maria Deli. The poemsare from his book “Love’s Sinning Song andOther Poems”. Both of them deal with hisfather, Italo, who died at the age of sixty. ItaloDe Iuliis was a shepherd in his native town ofCampotosto. For almost twenty-five years inCanada he worked on construction sites and infactories, and for the last years of his life in ahardware store because his ill health did notallow him to do the heavy work he had pre-viously done. It was perhaps his father whomore than anyone else who instilled inCelestino the deep sense of love and respectfor Italy, for Abruzzo and above all for theirhome town, Campotosto. His father wouldspeak of it at every festival, every meal, everygathering of the clan with nostalgia and tender-ness. But he never saw his home town againafter leaving it in 1952. The young boy wasencouraged by his father to copy out para-graphs from an old Italian speller which he hadprocured somewhere, and one can imaginewith what scant desire and little profit the littleboy immersed in Canadian ways all day atschool faced that task. In fact, after studyingItalian on his own at high school, he beganseriously to acquire the language at universityand through his activity as an actor and direc-tor of la Compagnia dei Giovani, a communitytheatre company which had its roots in theUniversity of Toronto Italian Club and overalmost two decades produced plays byPirandello, Machiavelli, Goldoni, Dario Fo andothers. Today he lives with his mother and hisolder son, Marco. His other son, Frederic,lives with his own mother but they all see eachother often. He teaches mathematics atGeorge Brown College, is and insurancebroker and translates from Italian into English.Aside from doing the English translation forAbruzzo-Italia, he has translated several booksand is working on a new English translation in“terza rima” of Dante’s Inferno, the first canti-cle of the Divina commedia.

Le campane

di Campotosto

Campotosto è a 1450 metri.

L'inverno è lungo. Tanti anni fa

bisognava prepararsi per sopravvive-

re durante i sei mesi in cui le attività

fuori di casa diventavano praticamen-

te impossibili. Le storie della fame

sofferta da tante famiglie sono molte.

Italo De Iuliis, a cui é dedicata questa

poesia, non e' mai piu' tornato a

Campotosto da dove era partito nel

1952. E' sepolto a Toronto. Però le

campane di Campotosto lo hanno

ricordato "suonando a morto" per lui,

come fanno per ognuno nato lì che

lascia questo mondo, e hanno raccol-

to il suo spirito tra i suoi monti. Nella

lingua inglese il suono dellle campa-

ne si scrive "ding dong".

27

Din Don

When church bells ring

four thousand miles away

there in those hills that do not bear

the fruit of former years,

when hardier hands caressed

small plots of land

- made smaller by the passing generations -

and repeat the nourishment for a six-month

sleep beneath the snow,

that is the way they sound

din don

at vespers and at morning mass,

and when the joyous festivals arrive

they swing in wild surrender

under the sun of August

singing their crazed song

din don din din don

din don din din don

while the growing hands of boy

engage in mortal combat

the writhing rope

beneath the dancing bronze.

You had not heard them pealing

in your tongue,

those bells that had announced

your coming hither,

for twenty-five long years.

But they had not forgotten you,

who in your time had made them sing

while waiting patiently to be a man

possessing his own flock.

Four thousands miles away

one day in March

the bells remembered

as the slow sad constant note

rang don

rang don

rang don

and welcomed you back home

amongst your

hills.

Din Don

Quando le campane suonano

a quattromila miglia da qui

su quei monti che non producono più

i frutti di una volta,

quando mani più provette accarezzavano

piccoli pezzi di terra

- resi più piccoli dal trascorrere delle generazioni -

e ne traevano il nutrimento per sei mesi

di sonno sotto la neve,

è così che suonano

din don

ai vespri e alla messa mattutina,

e quando arrivano le festività gioiose

oscillano in selvaggio abbandono

nel sole di agosto

cantando la loro canzone impazzita

din don din din don

din don din din don

mentre le mani crescenti dei ragazzi

combattono in mortale impegno

con la fune che si torce

sotto il bronzo che balla.

Tu non sentivi nella tua lingua

quello scampanio

delle campane che avevano annuziato

la tua venuta al mondo

da venticinque lunghi anni.

Ma non si erano dimenticate di te,

che ai tuoi tempi le avevi fatte cantare

mentre aspettavi pazientemente di diventare un uomo

con un gregge tutto suo.

A quattromila miglia di distanza

un giorno di marzo

quelle campane ti hanno ricordato

mentre una monotona e triste nota

suonava don

suonava don

suonava don

per riaccoglierti a sé

tra i tuoi monti.

(Traduzione dall’inglese di Giuliano Di Tanna)

Questa poesia di Celestino De Iuliis è trattadalla raccolta "Love’s Sinning Song and OtherPoems" (Il canto peccaminoso dell’amore edaltre poesie) ed è dedicata a suo padre Italo,prematuramente scomparso all'età di 60 anni

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

28

Questo brano é tratto

dalla raccolta di ricordi

con la quale Enza,

Rosanna e Carmela Di

Pierdomenico, che ora

vivono a Woodbrige

(Ontario), si sono classi-

ficate seconde nella

Sezione Italiani all'Estero

del 4° Premio Nazionale

di Letteratura

Naturalistica "Parco

Majella", svoltosi ad

Abbateggio (Pescara)

il 29 luglio 2001.

Quando si hanno 4 anni, non si capisce bene la parola "emigrare". Non si capisce fin-

ché non si arriva a destinazione e poi tutto diventa molto chiaro. Dover partire…. Mi

ritornano in mente solamente piccoli eventi come l'alzarsi prestissimo al buio e al fred-

do. Riscaldarsi vicino al fuoco mentre la nonna mi veste, mi prepara la colazione, e piange.

Una macchina che arriva per portarci a Roma. Abbracci stretti, visi bagnati di lacrime, e tre

persone che salutano, lasciate davanti al portone. Ogni tanto si portano una mano al viso per

asciugare le lacrime mia nonna, mio nonno, e mia zia.

Un viaggio in macchina interminabile, senza sapere che mi aspettava un viaggio ancora più

lungo. L'aereo che decolla, un bicchiere che mi si rovescia addosso, un cibo che mi disturba,

e finalmente il sonno.

L'arrivo a Montreal… un aereoporto immenso e delle persone che parlano una lingua stra-

niera. La mia mamma, tra le lacrime, non sa cosa chiedono, ma finalmente riesce a capire

che questi sono della dogana e vogliono controllare tutti i nostri bagagli. Un mare di cose

sparse dappertutto, e mia madre, che piange ancora di più e rimette tutto pazientemente a

posto. Io, presa dalla stanchezza, mi distendo supina sul pavimento freddo e duro della sala.

Partiredi Enza Di Pierdomenico

Addio agli amici. Qui accanto

e a destra: gli amici accompagnano

alla stazionedi Pescina

Giuliano Morgani,in partenza per

il Canada.

29

When you’re four you don’t even know what the word “emigrate” means. You don’t

understand until you get to where you’re going. Then everything becomes much

clearer. Leaving: I can only cull little things from my memory, like having to get up

very early when it’s still dark and cold. Warming up by the fire while my grandmother dres-

ses me, makes my breakfast and begins to cry. A car comes to take us to Rome.

Everybody hugging for dear life, faces wet with tears and three people waving good-bye,

left behind in front of the doorway. They keep bringing their hands up to their faces to wipe

away the tears: my grandmother, my grandfather, my aunt.

An endless trip in the car, without knowing that in store for me there was an even longer

journey. The plane taking off, a glass of something spilling all over me and finally, sleep.

Arriving in Montreal: an immense airport and people speaking in a foreign tongue. My

mother, through her tears doesn’t know what they’re asking, but she finally realizes they

are customs officers and they want to look though our luggage. A sea of belongings scat-

tered everywhere and my mother, crying even more profusely patiently putting things back

in place. And me, overcome by fatigue, lying on the cold, hard floor of the lounge. Another

The following is taken from a collection of memoirs which won Enza, Rosanna and

Carmela Di Pierdomenico, who now live in Woodbridge, Ontario, second prize in the

Italians Abroad section of the 4th “Parco Maiella” National Awards for Naturalistic

Literature awarded at Abbateggio (Pescara) on July 29, 2001.

Leavingby Enza Di Pierdomenico

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

30

Un altro aereo che ci porta a Toronto.

Papà che mi abbraccia dopo tanto tempo e parenti, zii e cugini, tutti che parlano l'inglese.

Tutto mi sembra così strano: le case, le persone, i negozi che hanno tutto cibo inglese

come "chicken soup", che non mi piace affatto, ma mia zia me lo fa mangiare tutti i giorni

per pranzo, e "corn flakes", che mangio per colazione. La mia vita cambia completamen-

te. Abitiamo al piano superiore della casa di mia zia. Di giorno lavorano gli uomini - mio

padre e mio zio - e di notte lavorano le donne - mia mamma e mia zia. Io e mia sorella, tra-

scorriamo le sere in compagnia di tutti gli uomini, ed impariamo ad amare lo sport, l'hockey,

perché è l'unica cosa che guardiamo in TV.

I miei compagni sono i cugini che si sforzano di parlare un po’ di italiano ma riescono a dire

poche parole in dialetto. A scuola ci sono delle persone con nomi strani come Linda, Doris,

Rennie, William, Jeff, ma che pensano che il mio nome sia ancora più strano. Sono così

antipatica ad uno di questi che un giorno mi dà un bel pugno allo stomaco, e rimango senza

fiato. Mi portano all'ufficio del preside dove viene mia sorella e ritorniamo a casa insieme.

Così sento per la prima volta, di non appartenere, e questo sentimento si ripete tante volte.

Man mano che mi abituo al Canada, mi rendo conto di essere diversa dagli altri, e tornan-

do in Italia, la prima volta, mi rendo conto che non sono nemmeno come gli italiani. E' pro-

prio strano non sentirsi parte di nessuna nazione e quindi ho capito che l'emigrato perde,

non solo la propria nazionalità, ma anche la sua identità: Diventa un'altra persona. Prima,

questo fatto mi faceva soffrire, ma oggi mi considero una persona unica perché ho visto sia

i lati positivi che negativi delle due culture (italiana e inglese) e posso scegliere di adotta-

re solo i costumi positivi di tutte e due.

In posa prima di lasciare il paese.Qui accanto da sinistra: Maria,

Mimmo e Nunziatina Presutto di Tocco Casauria nel 1957, prima di lasciare l’Abruzzo

per il Canada. Maria, che oggi é la presidente della Federazione

degli abruzzesi del Canada, hasposato Giuliano Morgani,

primo a sinistra nella foto dellapagina accanto, con i familiari. La foto della famiglia Morgani

é stata scattataalla stazione di Pescina il giorno

della partenza per il Canada

31

plane taking us to Toronto.

Dad hugging me after so long, relatives, uncles and cousins, everyone speaking English.

Everything strikes me as so strange: the houses, the people, the stores filled with English

food like “chicken soup”, which I don’t like at all but which my aunt makes me eat every day

for lunch, and “corn flakes” which I have for breakfast. My life changes completely. We

live on the second floor of my aunt’s house. At night the men work – my father and my

uncle – and in the evening the women work – my mother and my aunt. My sister and I

spend the evenings in the company of the men and we learn to love sports, hockey, becau-

se it’s the only thing we watch on T. V.

My friends are my cousins who try to speak Italian but can only say a few words in dia-

lect. At school there are people with strange names like Linda, Doris, Rennie, William, Jeff

but who think my name is even more strange. One of them hates me so much that one

day he punches me in the stomach and I’m left gasping for breath. They take me to the

principal’s office accompanied by my sister and we go home together. So for the first time

I feel what it’s like not to belong, a feeling I would know often.

As I get used to Canada, I realize that I’m different from the others, and going back to

Italy for the first time, I realize I’m not like Italians either. It’s really odd not feeling like you

are part of any nation and so I came to realize that an emigrant loses not only his nationa-

lity, but his identity as well. He becomes another person. At first I found this painful; but

today I feel I’m unique because I’ve seen both the positive and the negative aspects of the

two cultures (Italian and English) and I can choose to make only the positive aspects of the

two mine.

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

32

La Union Station é il luogo sim-

bolo dell'emigrazione in

Canada. Da qui, negli ultimi

cento anni, é passata la stragrande mag-

gioranza degli immigrati arrivati a Toronto,

sia che venissero da Halifax, sia che

entrassero dagli Stati Uniti dopo essere

sbarcati a New York.

Ogni italiano giunto qui prima degli anni

Sessanta conserva nitido nella memoria il

momento in cui é sceso dal treno a Union

Station. Ricorda la rampa di scale con i

corrimano di ottone che portava nell'enor-

me atrio dal pavimento di granito grigio

gremito di parenti, amici, conoscenti, in

attesa dei nuovi arrivati. Per tutti loro la

prima immagine di Toronto é stata quella

di Downtown, il centro della città, mentre

sbucavano fra le gigantesche colonne di

Union Station. Fuori li aspettava un paese

di cui non conoscevano né lingua, né

leggi, né usanze, e la dura vita dell'emi-

grante in una terra straniera.

Memore di quel primo impatto con il

nuovo mondo la comunità italo-canadese

ha voluto donare un monumento alla città

La Union Station

La Union Station, la stazione ferro-viaria di Toronto si trova proprio

nel cuore della città, che all'iniziodell'800 si chiamava York. L’attualeedificio neoclassicheggiante, con lesue enormi colonne, è stato finitosolo nel 1919, subito dopo la primaguerra mondiale, quando il treno erada tempo il principale mezzo di tra-sporto del paese. Lo era già nel 1867,quando vide la luce il Dominion ofCanada che riuniva le quattro provin-ce dell'Ontario, Québec, NewBrunswick e Nova Scotia. Ed erastata proprio la promessa di un colle-gamento ferroviario con il centro delpaese a convincere alcune provincedell'Ovest ad unirsi al resto dellanazione.

Union Station

Union Station, the railway stationof Toronto is located downtown,

in the heart of the city which, at thebeginning of the nineteenth centrewas called York. The present neo-classical building, with its hugecolumns, was finished only in 1919,immediately after the first world warwhen the train had been the principalmeans of transport in the country forquite some time. Indeed, the trainwas already indispensable in 1867when the Dominion of Canada wasborn bringing under one governmentthe four provinces of Ontario,Quebec, New Brunswick and NovaScotia. And it was the promise of arailway from sea to sea (a mari usquead mare), that convinced some of thewestern provinces to join confedera-tion.

Il Monumento

33

Union Station is a symbol of immigra-

tion to Canada. Over the last one

hundred years the majority of immi-

grants coming to Toronto passed through its

cavernous interior, whether they arrived at

Halifax or through the United States via Buffalo

and Niagara Falls after landing in New York.

Every Italian who came to Toronto before the

sixties has clearly imprinted in his memory the

moment when he got off the train at Union

Station. He remembers coming down the stair-

case with the brass railing, entering the huge

granite covered waiting area where crowds of

relatives, parents and friends were milling about

ready to greet the new arrivals with tears and

laughter. For all of them, their first look at

Toronto was the downtown view which faced

them as they emerged from between the giant

columns of Union Station. Whether they exited

in winter snow or summer heat, they were all

coming to be part of a country of which they

knew neither language, nor laws, nor customs.

They came ready to brave the initial, usually

hard and sometimes harsh reality faced by any

immigrant in a strange land. But that first

moment was usually one of joyous euphoria.

Monumento al MulticulturalismoThe Monument to Multiculturalism

Union Station è il luogo simbolo dell’emigrazione italianain Canada. Qui é stato posto il monumento donato dallacomunità italo-canadese alla città di Toronto.

34

che li aveva

ospitati e

accolti come suoi

cittadini. Un

monumento per

ricordare non solo

la loro presenza,

ma anche il fatto,

forse ancora più

significativo, che

negli ultimi 50 anni

Toronto era diven-

tata, grazie anche

a loro, la città più

"multiculturale" del

mondo. Un termi-

ne coniato in que-

sta metropoli dove

oggi più della

metà della popola-

zione non é di ori-

gine anglosasso-

ne o francese.

Sotto la guida di Laureano Leone, uno

dei leader della comunità, coadiuvato per

la parte organizzativa da Nivo Angelone,

un comitato di italo-canadesi organizzò

una raccolta di fondi da destinare alla

costruzione del monumento. Furono rac-

colti oltre centomila dollari. Ma all'inizio l'i-

dea trovò diversi oppositori. A molti non

piaceva che la statua fosse situata in un

luogo così significativo come la Union

Station: se la comunità italo-canadese

voleva un monumento che lo ponessero

in un edificio privato, sostenevano. Altri

ancora volevano che l'artista incaricato di

realizzare la statua fosse un canadese e

non un italiano. Ma alla fine il comitato la

spuntò su tutti. La statua in bronzo, alta

quattro metri, fu ideata dall'artista abruz-

zese Francesco Perilli che realizzò una

figura maschile, senza tratti sul viso che

lo potessero identificare come apparte-

nente a una particolare etnia, nell'atto di

congiungere due meridiani del mondo cir-

condato da un volo di colombe, simbolo di

pace.

Mindful of

this first

encounter with a

new world, the

Italian Canadian

community deci-

ded at one point

that it would

donate a monu-

ment to this city

which had welco-

med and taken

them in as its citi-

zens. A monu-

ment that would

c o m m e m o r a t e

not only their pre-

sence here, but

also the fact,

perhaps of even

greater significan-

ce, that in the last

fifty years Toronto

had become,

thanks also in

part to them, the most “multicultural”, eth-

nically diverse city in the world. The term

multiculturalism itself was coined in

Canada and is most germane to this

metropolis in which well over half of its

population is of non Anglo-Saxon, non

French origin. Under the leadership of Dr.

Laureano Leone, one of the best-known

members of the Italian Canadian commu-

nity, aided by the organizational acumen

of Nivo Angelone, a committee of Italian

Canadians was struck to raise the neces-

sary funds for creating the monument.

Over one hundred thousand dollars was

raised. The idea, however, met with some

opposition, at first. Some of those oppo-

sed didn’t want the statue to be situated in

such a symbolically important place as

Union Station: If the Italian Canadian

community wanted a monument, they

argued, let them erect it on private pro-

perty. Others objected that it should be a

home-grown Canadian artist to execute

such an ambitious project not one who

was Italian and didn’t live here But in the

L�ABRUZZO IN CANADA

end, the committee won the day. The

bronze statue is over four metres tall

and was created and executed by

Francesco Perilli, an artist from Abruzzo.

It consists of a male figure, with no facial

features that might in any way suggest a

particular ethnic origin, struggling to join

together a great circle of longitude, sur-

rounding by fluttering doves symbolizing

peace. The strain of the figure is emble-

matic of the enormous commitment

necessary in Canada to keep united all

the various cultures and ethnic groups

without annihilating the importance of

their distinct, individual identities and

diversity, indeed, leaving them free to

grow and develop within the cultural

mosaic symbolic of Canada’s policies

towards its citizens. It is a political choice

which clearly sets its apart from America’s

melting pot mentality of trying to absorb

and homogenize all groups entering its

borders. Today the statue, which was

donated to the city of Toronto during cele-

brations for the one hundred and fiftieth

anniversary of its founding, has become a

universally recognized icon of multicultu-

ralism in Canada and is prominently cited

in books and tourist guides. This year, in

fact, a picture of the stature to multicultu-

ralism has been chosen to adorn the

cover of Toronto’s telephone directory, a

list of over a million names representing

every corner of the globe. On its simple

base, designed by a Canadian citizen of

Abruzzese origin, the architect Nino Rico,

there are three commemorative bronze

plaques, one of which reproduces Article

27 of the International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights, the 1971 Official

Statement on Multiculturalism by the

House of Commons of Canada, and

Article 27 (on multiculturalism) of the

Canadian Charter of Rights and

Freedoms on the Canadian Constitution.

Another lists the names of donors and a

third explains why the monument was

erected and lists the names of the com-

mittee members without whose commit-

ment this would not have been possible.

Lo sforzo dell'uomo rappresenta

l'enorme impegno del Canada nel-

l'unire tutte le culture e le etnie del paese

senza annullarne le diversità, ma lascian-

dole indipendenti come le tessere di un

grande mosaico. Una scelta politica molto

diversa da quella adottata negli Stati Uniti,

dove le varie etnie, come in un crogiuolo

("melting pot") sono state costrette a

uniformarsi alla cultura del paese che le

ospitava. Oggi la statua é diventata il sim-

bolo universale del multiculturalismo del

Canada, é citata in molti libri e quest'anno

é stata scelta per illustrare la copertina

della guida telefonica di Toronto. Un elen-

co di oltre un milione di nomi che rappre-

sentano ogni angolo del mondo.

Sulla semplice e scarna base ideata da

un altro abruzzese, l'architetto Nino Rico,

sono fissate tre targhe che ricordano le

norme sul multiculturalismo e i diritti civili,

i nomi del comitato e degli autori del

monumento e quelli delle famiglie e delle

aziende che hanno contribuito alla sua

costruzione. L'opera é dedicata alla

memoria di tredici immigrati italiani.

35

Lo scultore e l’inaugurazione.Qui sopra: l’abruzzese FrancescoPerilli al lavoro nel suo atelier.Pagina accanto: l’inaugurazione del monumento donato alla città in occasione del 150° anniversaiodella sua fondazione. Primi a sinistrae a destra nella foto: Nivo Angelonee, seminascosto, Laureano Leone.