Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

-

Upload

virgilioilari -

Category

Documents

-

view

228 -

download

0

Transcript of Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

1/53

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

2/53

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

3/53

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

4/53

NAVIGARE NECESSE ESTNon solo per gli appassionati di storia navale,

ma per tutti gli amanti del mare e della classicit,

ed in particolare per coloro che, come me,non sanno sottrarsi al fascino della civilt romana.di DOMENICO CARRO

Introduzione (in Italiano): genesi e nome di questo sito Web. Parte I

VETRINA CLASSICA sulla storia navale e marittima dell'antica Roma (in Italiano):elementi relativi alla ricerca che da diversi anni sto conducendo al fine di pervenire ad una migliore messa afuoco degli aspetti navali e marittimi del mondo romano. Dati sulle pubblicazioni maggiori (situazione eprogetti) e bibliografia delle fonti antiche.

Parte IIROMA MARITTIMA - Roma Eterna sul mare (in Italiano, con un po' di Francese e un po' di Inglese):

altri miei contributi alla ricostruzione della storia navale e marittima dell'antica Roma e alla conoscenza dei

Romani che si sono illustrati sul mare. Contiene alcuni saggi, qualche altro scritto minore e una bibliografia difonti moderne.

Parte IIITESTI ANTICHI (in Italiano e Latino): alcuni scritti poco conosciuti, che trattano questioni navali omarittime secondo gli usi degli antichi Romani.

Parte IVCONTRIBUTI ESTERNI (in Italiano): spazio predisposto per ospitare scritti di altri autori, quali ulterioricontributi alla conoscenza della storia navale e marittima dell'antica Roma.

Parte VGALLERIA NAVALE (in Italiano): selezione di immagini navali romane (affreschi, mosaici, bassorilievi,sculture, monete e altri reperti) pubblicate su Classica o sulla Rete.

Accreditamenti (titoli in Italiano e Inglese; commenti in Italiano):Guida alle risorse Internet d'interesse per la ricerca di altri elementi relativi alla storia navale e marittima

dell'antica Roma.

ROMA, 30-XI-2007

Ritorno a R O M A A E T E R N A

http://www.romaeterna.org/navigare.html

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

5/53

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaThe Roman Navy (Latin: Classis, lit. "fleet") comprised the naval forces of the Ancient Roman state. Although thenavy was instrumental in the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean basin, it never enjoyed the prestige of the Roman

legions. Throughout their history, the Romans remained a primarily land-based people, and relied on their morenautically inclined subjects, such as the Greeks and the Egyptians, to build and man their ships. Partly because of this,the navy was never wholly embraced by the Roman state, and deemed somewhat "un-Roman".

[1]In Antiquity, navies

and trading fleets did not have the logistical autonomy that modern ships and fleets possess. Unlike modern navalforces, the Roman navy even at its height never existed as an autonomous service, but operated as an adjunct to theRoman army.During the course of the First Punic War, the Roman navy was massively expanded and played a vital role in the

Roman victory and the Roman Republic's eventual ascension to hegemony in the Mediterranean Sea. In the course ofthe first half of the 2nd century BC, Rome went on to destroy Carthage and subdue the Hellenistic kingdoms of theeastern Mediterranean, achieving complete mastery of the inland sea, which they called Mare Nostrum. The Roman

fleets were again prominent in the 1st century BC in the wars against the pirates, and in the civil wars that brought downthe Republic, whose campaigns ranged across the Mediterranean. In 31 BC, the great naval Battle of Actium ended thecivil wars culminating in the final victory ofAugustus and the establishment of the Roman Empire.

During the Imperial period, the Mediterranean became a peaceful "Roman lake"; in the absence of a maritime enemy,the navy was reduced mostly to patrol and transport duties. On the fringes of the Empire however, in new conquests or,increasingly, in defense against barbarian invasions, the Roman fleets were still engaged in warfare. The decline of theEmpire in the 3rd century took a heavy toll on the navy, which was reduced to a shadow of its former self, both in size

and in combat ability. As successive waves of the Vlkerwanderung crashed on the land frontiers of the batteredEmpire, the navy could only play a secondary role. In the early 5th century, the Roman frontiers were breached, andbarbarian kingdoms appeared on the shores of the western Mediterranean. One of them, the Vandal Kingdom, raised anavy of its own and raided the shores of the Mediterranean, even sacking Rome, while the diminished Roman fleets

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

6/53

were incapable of offering any resistance. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in the late 5th century. The subsequent

Roman Navy of the enduring Eastern Roman Empire is called by historians the Byzantine Navy.Early Republic The exact origins of the Roman fleet are obscure. A traditionally agricultural and land-based society,the Romans rarely ventured out to sea, unlike their Etruscan neighbours.

[2]There is evidence of Roman warships in the

early 4th century BC, such as mention of a warship that carried an embassy to Delphi in 394 BC, but at any rate, theRoman fleet, if it existed, was negligible.

[3]The traditional birth date of the Roman navy is set at ca. 311 BC, when,

after the conquest ofCampania, two new officials, the duumviri navales classis ornandae reficiendaeque causa, weretasked with the maintenance of a fleet.

[4][5]As a result, the Republic acquired its first fleet, consisting of 20 ships, most

likely triremes, with each duumvircommanding a squadron of 10 ships.[3][5]

However, the Republic continued to relymostly on her legions for expansion in Italy; the navy was most likely geared towards combating piracy and lackedexperience in naval warfare, being easily defeated in 282 BC by the Tarentines.

[5][6][7]

This situation continued until the First Punic War: the main task of the Roman fleet was patrolling along the Italiancoast and rivers, protecting seaborne trade from piracy. Whenever larger tasks had to be undertaken, such as the navalblockade of a besieged city, the Romans called on the allied Greek cities of southern Italy, thesocii navales, to provideships and crews.

[8]It is possible that the supervision of these maritime allies was one of the duties of the four new

praetores classici, who were established in 267 BC.[9]

First Punic War The first Roman expedition outside mainland Italy was against the island ofSicily in 265 BC. This ledto the outbreak of hostilities with Carthage, which would last until 241 BC. At the time, the Punic city was the

unchallenged master of the western Mediterranean, possessing a long maritime and naval experience and a large fleet.

Although Rome had relied on her legions for the conquest of Italy, operations in Sicily had to be supported by a fleet,and the ships available by Rome's allies were clearly insufficient.

[9]Thus in 261 BC, the Roman Senate set out to

construct a fleet of 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes.[8]

According to Polybius, the Romans seized a shipwreckedCarthaginian quinquereme, and used it as a blueprint for their own ships.

[10]The new fleets were commanded by the

annually elected Roman magistrates, but naval expertise was provided by the lower officers, who continued to beprovided by thesocii, mostly Greeks. This practice was continued until well into the Empire, something also attested by

the direct adoption of numerous Greek naval terms.[11][12]

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and couldnot hope to match them in naval tactics, which required great maneuverability and experience. They therefore employed

a novel weapon which transformed sea warfare to their advantage. They equipped their ships with the corvus, possiblydeveloped earlier by the Syracusans against the Athenians. This was a long plank with a spike for hooking onto enemyships. Using it as a boarding bridge, marines were able toboard an enemy ship, transforming sea combat into a versionof land combat, where the Roman legionaries had the upper hand. However, it is believed that the corvus'weight made

the ships unstable, and could capsize a ship in rough seas.[13]

Although the first sea engagement of the war, the Battle of the Lipari Islands in 260 BC, was a defeat for Rome, theforces involved were relatively small. Through the use of the corvus, the fledgling Roman navy under Gaius Duilius

won its first major engagement later that year at the Battle of Mylae. During the course of the war, Rome continued tobe victorious at sea: victories at Sulci (258 BC) and Tyndaris (257 BC) were followed by the massiveBattle of CapeEcnomus, where the Roman fleet under the consuls Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius inflicted a severe

defeat on the Carthaginians. This string of successes allowed Rome to push the war further across the sea to Africa andCarthage itself. Continued Roman success also meant that their navy gained significant experience, although it alsosuffered a number of catastrophic losses due to storms, while conversely, the Carthaginian navy suffered fromattrition.

[13]

The Battle of Drepana in 249 BC resulted in the only major Carthaginian sea victory, forcing the Romans to equip anew fleet from donations by private citizens. In the last battle of the war, at Aegates Islands in 241 BC, the RomansunderGaius Lutatius Catulus displayed superior seamanship to the Carthaginians, notably using their rams rather than

the now-abandoned corvus to achieve victory.[13]

Illyria and the Second Punic War After the Roman victory, the balance of naval power in the Western Mediterraneanhad shifted from Carthage to Rome.

[14]This ensured Carthaginian acquiescence to the conquest of Sardinia and Corsica,

and also enabled Rome to deal decisively with the threat posed by the Illyrian pirates in the Adriatic. The Illyrian Warsmarked Rome's first involvement with the affairs of the Balkan peninsula.

[15]Initially, in 229 BC, a fleet of 200

warships was sent against Queen Teuta, and swiftly expelled the Illyrian garrisons from the Greek coastal cities ofmodern-day Albania.

[14]Ten years later, the Romans sent another expedition in the area against Demetrius of Pharos,

who had rebuilt the Illyrian navy and engaged in piracy up into the Aegean. Demetrius was supported by Philip V ofMacedon, who had grown anxious at the expansion of Roman power in Illyria.

[16]The Romans were again quickly

victorious and expanded their Illyrian protectorate, but the beginning of the Second Punic War (218201 BC) forced

them to divert their resources westwards for the next decades.Due to Rome's command of the seas, Hannibal, Carthage's great general, was forced to eschew a sea-borne invasion,instead choosing to bring the war over land to the Italian peninsula.

[17]Unlike the first war, the navy played little role on

either side in this war. The only naval encounters occurred in the first years of the war, at Lilybaeum (218 BC) and theEbro River(217 BC), both resulting Roman victories. Despite an overall numerical parity, for the remainder of the warthe Carthaginians did not seriously challenge Roman supremacy. The Roman fleet was hence engaged primarily withraiding the shores of Africa and guarding Italy, a task which included the interception of Carthaginian convoys of

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

7/53

supplies and reinforcements for Hannibal's army, as well as keeping an eye on a potential intervention by Carthage's

ally, Philip V.[18]

The only major action in which the Roman fleet was involved was the siege of Syracuse in 214-212BC with 130 ships under Marcus Claudius Marcellus. The siege is remembered for the ingenious inventions ofArchimedes, such as mirrors that burned ships or the so-called "Claw of Archimedes", which kept the besieging army at

bay for two years.[19]

A fleet of 160 vessels was assembled to support Scipio Africanus' army in Africa in 202 BC, and,should his expedition fail, evacuate his men. In the event, Scipio achieved a decisive victory at Zama, and the

subsequent peace stripped Carthage of its fleet.[20]

Operations in the East Rome was now the undisputed mistress of the Western Mediterranean, and turned her gaze

from defeated Carthage to the Hellenistic world. Small Roman forces had already been engaged in the First MacedonianWar, when, in 214 BC, a fleet underMarcus Valerius Laevinus had successfully thwarted Philip V from invading Illyriawith his newly-built fleet. The rest of the war was carried out mostly by Rome's allies, the Aetolian League and later theKingdom of Pergamon, but a combined Roman-Pergamene fleet of ca. 60 ships patrolled the Aegean until the war's endin 205 BC. In this conflict, Rome, still embroiled in the Punic War, was not interested in expanding her possessions, butrather in thwarting the growth of Philip's power in Greece. The war ended in an effective stalemate, and was renewed in201 BC, when Philip V invaded Asia Minor. A naval battle offChios ended in a costly victory for the Pergamene-

Rhodian alliance, but the Macedonian fleet lost many warships, including its flagship, a deceres.[21]

Soon after,Pergamon and Rhodes appealed to Rome for help, and the Republic was drawn into the Second Macedonian War. Inview of the massive Roman naval superiority, the war was fought on land, with the Macedonian fleet, already weakened

at Chios, not daring to venture out of its anchorage at Demetrias.[21]

After the crushing Roman victory at

Cynoscephalae, the terms imposed on Macedon were harsh, and included the complete disbandment of her navy.Almost immediately following the defeat ofMacedon, Rome became embroiled in a warwith the Seleucid Empire. This

war too was decided mainly on land, although the combined Roman-Rhodian navy also achieved victories over theSeleucids at Myonessus and Eurymedon. These victories, which were invariably concluded with the imposition of peacetreaties that prohibited the maintenance of anything but token naval forces, spelled the disappearance of the Hellenisticroyal navies, leaving Rome and her allies unchallenged at sea. Coupled with the final destruction of Carthage, and the

end ofMacedon's independence, by the latter half of the 2nd century BC, Roman control over all of what was later to bedubbed mare nostrum ("our sea") had been established. Subsequently, the Roman navy was drastically reduced,depending on its Greek allies to supply ships and crews as needed.

[22]

Late Republic

Mithridates and the pirate threatIn the absence of a strong naval presence however,piracy flourished throughout theMediterranean, especially in Cilicia, but also in Crete and other places, further reinforced by money and warshipssupplied by King Mithridates VI of Pontus, who hoped to enlist their aid in his wars against Rome.

[23]In the First

Mithridatic War(8985 BC), Sulla had to requisition ships wherever he could find them to counter Mithridates' fleet.Despite the makeshift nature of the Roman fleet however, in 86 BC Lucullus defeated the Pontic navy at Tenedos.

[24]

Immediately after the end of the war, a permanent force of ca. 100 vessels was established in the Aegean from the

contributions of Rome's allied maritime states. Although sufficient to guard against Mithridates, this force was totallyinadequate against the pirates, whose power grew rapidly.

[24]Over the next decade, the pirates defeated several Roman

commanders, and raided unhindered even to the shores of Italy, reaching Rome's harbor, Ostia.[25]

According to the

account of Plutarch, "the ships of the pirates numbered more than a thousand, and the cities captured by them fourhundred."

[26]Their activity posed a growing threat for the Roman economy, and a challenge to Roman power: several

prominent Romans, including twopraetors with their retinue and the young Julius Caesar, were captured and held forransom. Perhaps most important of all, the pirates disrupted Rome's vital lifeline, namely the massive shipments of

grain and other produce from Africa and Egypt that were needed to sustain the city's population.[27]

The resulting grain shortages were a major political issue, and popular discontent threatened to become explosive. In 74BC, with the outbreak of the Third Mithridatic War, Marcus Antonius (the father of Mark Antony) was appointed

praetorwith extraordinary imperium against the pirate threat, but signally failed in his task: he was defeated off Crete in72 BC, and died shortly after.

[28]Finally, in 67 BC theLex Gabinia was passed in the Plebeian Council, vesting Pompey

with unprecedented powers and authorizing him to move against them.[29]

In a massive and concerted campaign,

Pompey cleared the seas from the pirates in only three months.[22][30]

Afterwards, the fleet was reduced again to policingduties against intermittent piracy.

Caesar and the Civil Wars

In 56 BC, for the first time a Roman fleet engaged in battle outside the Mediterranean. This occurred during JuliusCaesar's Gallic Wars, when the maritime tribe of the Veneti rebelled against Rome. Against the Veneti, the Romanswere at a disadvantage, since they did not know the coast, and were inexperienced in fighting in the open sea with itstides and currents.

[31]Furthermore, the Veneti ships were superior to the light Roman galleys. They were built of oak

and had no oars, being thus more resistant to ramming. In addition, their greater height gave them an advantage in bothmissile exchanges and boarding actions.

[32]In the event, when the two fleets encountered each other in Quiberon Bay,

Caesar's men resorted to the use of hooks on long poles, which cut the halyards supporting the Veneti sails.[33]

Immobile, the Veneti ships were easy prey for the legionaries who boarded them.[34] Having thus established his controlof the English Channel, in the next years Caesar used this newly-built fleet to carry out two invasions of Britain.The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the civilwars that ended the Republic. In the East, the Republican faction quickly established its control, and Rhodes, the last

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

8/53

independent maritime power in the Aegean, was subdued by Gaius Cassius Longinus in 43 BC, after its fleet was

defeated offKos. In the West, against the triumvirs stood Sextus Pompeius, who had been given command of the Italianfleet by the Senate in 43 BC. He took control of Sicily and made it his base, blockading Italy and stopping thepolitically crucial supply of grain from Africa to Rome.

[35]After suffering a defeat from Sextus in 42 BC, Octavian

initiated massive naval armaments, aided by his closest associate, Marcus Agrippa: ships were built at Ravenna andOstia, the new artificial harbor ofPortus Julius built at Cumae, and soldiers and rowers levied, including over 20,000

manumitted slaves.[36]

Finally, Octavian and Agrippa defeated Sextus in the Battle of Naulochus in 36 BC, putting anend to all Pompeian resistance.

Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of Mark Antony and Cleopatra,Queen of Egypt, in the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, where Antony had assembled 500 ships against Octavian's 400ships.

[37]This last naval battle of the Roman Republic definitively established Octavian as the sole ruler over Rome and

the Mediterranean world. In the aftermath of his victory, he formalized the Fleet's structure, establishing several keyharbors in the Mediterranean (see below). The now fully professional navy had its main duties consist of protectingagainst piracy, escorting troops and patrolling the river frontiers of Europe. It remained however engaged in activewarfare in the periphery of the Empire.

Principate

Operations under Augustus UnderAugustus and after the conquest ofEgypt there were increasing demands from theRoman economy to extend the trade lanes to India. The Arabian control of all sea routes to India was an obstacle. One

of the first naval operations underprinceps Augustus was therefore the preparation for a campaign on the Arabian

peninsula. Aelius Gallus, the prefect of Egypt ordered the construction of 130 transports and subsequently carried10,000 soldiers to Arabia.

[38]But the following march through the desert towards Yemen failed and the plans for control

of the Arabian peninsula had to be abandoned. At the other end of the Empire, in Germania, the navy played animportant role in the supply and transport of the legions. In 15 BC an independent fleet was installed at the LakeConstance. Later, the generals Drusus and Tiberius used the Navy extensively, when they tried to extend the Romanfrontier to the Elbe. In 12 BC Drusus ordered the construction of a fleet of 1,000 ships and sailed them along the Rhine

into theNorth Sea.[39]

The Frisii and Chauci had nothing to oppose the superior numbers, tactics and technology of theRomans. When these entered the river mouths ofWeserand Ems, the local tribes had to surrender. In 5 BC the Romanknowledge concerning the North and Baltic Sea was fairly extended during a campaign by Tiberius, reaching as far as

the Elbe: Plinius describes how Roman naval formations came past Heligoland and set sail to the north-eastern coast ofDenmark, and Augustus himself boasts in hisRes Gestae: "My fleet sailed from the mouth of the Rhine eastward as faras the lands of the Cimbri to which, up to that time, no Roman had ever penetrated either by land or by sea...".

[40]The

multiple naval operations north of Germania had to be abandoned after the battle of the Teutoburg Forest in the year 9

AD.Julio-Claudian dynasty In the years 15 and 16, Germanicus carried out several fleet operations along the rivers Rhineand Ems, without permanent results due to grim Germanic resistance and a disastrous storm.

[41]By 28, the Romans lost

further control of the Rhine mouth in a succession of Frisian insurgencies. From 43 to 85, the Roman navy played animportant role in the Roman conquest of Britain. The classis Germanica rendered outstanding services in multitudinouslanding operations. In 46, a naval expedition made a push deep into the Black Sea region and even travelled on the

Tanais. In 47 a revolt by the Chauci, who took to piratical activities along the Gallic coast, was subdued by GnaeusDomitius Corbulo.

[42]By 57 an expeditionary corps reached Chersonesos (see Charax, Crimea).

It seems that underNero, the navy obtained strategically important positions for trading with India; but there was noknown fleet in the Red Sea. Possibly, parts of the Alexandrian fleet were operating as escorts for the Indian trade. In the

Jewish revolt, from 66 to 70, the Romans were forced to fight Jewish ships, operating from a harbour in the area ofmodern Tel Aviv, on Israel's Mediterranean coast. In the meantime several flotilla engagements on the Sea of Galileetook place.

In 68, as his reign became increasingly insecure, Nero raised legio IAdiutrix from sailors of the praetorian fleets. After Nero's overthrow, in 69, the "Year of the four emperors", the praetorian fleets supported Emperor Otho against theusurper Vitellius,

[43]and after his eventual victory, Vespasian formed another legion, legio II Adiutrix, from their

ranks.[44]

Only in the Pontus did Anicetus, the commander of the Classis Pontica, support Vitellius. He burned the fleet,and sought refuge with the Iberian tribes, engaging in piracy. After a new fleet was built, this revolt was subdued.

[45]

Flavian, Antonine and Severan dynasties

During the Batavian rebellion ofGaius Julius Civilis (69-70), the rebels got hold of a squadron of the Rhine fleet bytreachery,

[46]and the conflict featured frequent use of the Roman Rhine flotilla. In the last phase of the war, the British

fleet and legio XIV were brought in from Britain to attack the Batavian coast, but the Cananefates, allies of theBatavians, were able to destroy or capture a large part of the fleet.

[47]In the meantime, the new Roman commander,

Quintus Petillius Cerialis, advanced north and constructed a new fleet. Civilis attempted only a short encounter with hisown fleet, but could not hinder the superior Roman force from landing and ravaging the island of the Batavians, leadingto the negotiation of a peace soon after.

[48]

In the years 82 to 85, the Romans under Gnaeus Julius Agricola launched a campaign against the Caledonians inmodern Scotland. In this context the Roman navy significantly escalated activities on the eastern Scottish coast.

[49]

Simultaneously multiple expeditions and reconnaissance trips were launched. During these the Romans would capturethe Orkney Islands (Orcades) for a short period of time and obtained information about the Shetland Islands.

[50]There is

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

9/53

some speculation about a Roman landing in Ireland, based on Tacitus reports about Agricola contemplating the island's

conquest,[51]

but no conclusive evidence to support this theory has been found.Under the Five Good Emperors the navy operated mainly on the rivers; so it played an important role during Trajan'sconquest ofDacia and temporarily an independent fleet for the Euphrates and Tigris rivers was founded. Also during

the wars against the Marcomanni confederation underMarcus Aurelius several combats took place on the Danube andthe Tisza.

Under the aegis of the Severan dynasty, the only known military operations of the navy were carried out underSeptimius Severus, using naval assistance on his campaigns along the Euphrates and Tigris, as well as in Scotland.

Thereby Roman ships reached inter alia the Persian Gulfand the top of the British Isles.3rd century crisis As the 3rd century dawned, the Roman Empire was at its peak. In the Mediterranean, peace hadreigned for over two centuries, as piracy had been wiped out and no outside naval threats occurred. As a result,complacency had set in: naval tactics and technology were neglected, and the Roman naval system had becomemoribund.

[52]After 230 however and for fifty years, the situation changed dramatically. The so-called " Crisis of the

Third Century" ushered a period of internal turmoil, and the same period saw a renewed series of seaborne assaults,which the imperial fleets proved unable to stem.

[53]In the West, Picts and Irish ships raided Britain, while the Saxons

raided the North Sea, forcing the Romans to abandon Frisia.[53]

In the East, the Goths and other tribes from modernUkraine raided in great numbers over the Black Sea.

[54]These invasions began during the rule of Trebonianus Gallus,

when for the first time Germanic tribes built up their own powerful fleet in the Black Sea. Via two surprise attacks

(256) on Roman naval bases in the Caucasus and near the Danube, numerous ships fell into the hands of the Germans,

whereupon the raids were extended as far as the Aegean Sea; Byzantium, Athens, Sparta and other towns wereplundered and the responsible provincial fleets were heavily debilitated. It was not until the attackers made a tactical

error, that their onrush could be stopped.In 267270 another, much fiercer series of attacks took place. A fleet composed of Heruli and other tribes raided thecoasts ofThrace and the Pontus. Defeated offByzantium by general Venerianus,

[55]the barbarians fled into the Aegean,

and ravaged many islands and coastal cities, including Athens and Corinth. As they retreated northwards over land, they

were defeated by EmperorGallienus atNestos.[56]

However, this was merely the prelude to an even larger invasion thatwas launched in 268/269: several tribes banded together (the Historia Augusta mentions Scythians, Greuthungi,Tervingi, Gepids, Peucini, Celts and Heruli) and allegedly 2,000 ships and 325,000 men strong,

[57]raided the Thracian

shore, attacked Byzantium and continued raiding the Aegean as far as Crete, while the main force approachedThessalonica. EmperorClaudius II however was able to defeat them at the Battle of Naissus, ending the Gothic threatfor the time being.

[58]

Barbarian raids also increased along the Rhine frontier and in the North Sea. Eutropius mentions that during the 280s,

the sea along the coasts of the provinces of Belgica and Armorica was "infested with Franks and Saxons". To counterthem, Maximian appointed Carausius as commander of the British Fleet.

[59]However, Carausius rose up in late 286 and

seceded from the Empire with Britannia and parts of the northern Gallic coast.[60]

With a single blow Roman control of

the channel and the North Sea was lost, and emperorMaximinus was forced to create a completely new Northern Fleet, but in lack of training it was almost immediately destroyed in a storm.

[61]Only in 293, under Caesar Constantius

Chlorus did Rome regain the Gallic coast. A new fleet was constructed in order to cross the Channel,[62]

and in 296,

with a concentric attack on Londinium the insurgent province was retaken.[63]

Late Antiquity By the end of the 3rd century, the Roman navy had declined dramatically. Although EmperorDiocletian is held to have strengthened the navy, and increased its manpower from 46,000 to 64,000 men,

[64]the old

standing fleets had all but vanished, and in the civil wars that ended the Tetrarchy, the opposing sides had to mobilize

the resources and commandeered the ships of the Eastern Mediterranean port cities.[54]

These conflicts thus broughtabout a renewal of naval activity, culminating in the Battle of the Hellespont in 324 between the forces ofConstantine Iunder Caesar Crispus and the fleet of Licinius, which was the only major naval confrontation of the 4th century.

Vegetius, writing at the end of the 4th century, testifies to the disappearance of the old praetorian fleets in Italy, butcomments on the continued activity of the Danube fleet.

[65]In the 5th century, only the eastern half of the Empire could

field an effective fleet, as it could draw upon the maritime resources of Greece and the Levant. Although the NotitiaDignitatum still mentions several naval units for the Western Empire, these were apparently too depleted to be able tocarry out much more than patrol duties.

[66]At any rate, the rise of the naval power of the Vandal Kingdom under

Geiseric in North Africa, and its raids in the Western Mediterranean, were practically uncontested.[54]

Although there issome evidence of West Roman naval activity in the first half of the 5th century, this is mostly confined to trooptransports and minor landing operations.

[65]The historian Priscus and Sidonius Apollinaris affirm in their writings that

by the mid-5th century, the Western Empire essentially lacked a war navy.[67]

Matters became even worse after thedisastrous failure of the fleets mobilized against the Vandals in 460 and 468, under the emperors Majorian and

Anthemius.For the West, there would be no recovery, as the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed in 476. Inthe East however, the classical naval tradition survived, and in the 6th century, a standing navy was reformed.

[54]The

East Roman (Byzantine) navy would remain a formidable force in the Mediterranean until the 11th century.Organization The bulk of a ship's crew was formed by the rowers, the remiges (sing. remex) oreretai (sing. erets) inGreek. Despite popular perceptions, the Roman fleet, and ancient fleets in general, relied throughout its existence onrowers of free status. Galley slaves were usually not put at the oars, except in times of pressing manpower demands or

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

10/53

extreme emergency. Even then, they were employed after they had been freed.[68]

In Imperial times, non-citizen

freeborn provincials (peregrini), chiefly from nations with a maritime background such as Greeks, Phoenicians, Syriansand Egyptians formed the bulk of the fleets' crews.

[68][69]

During the early Principate, a ship's crew, regardless of its size, was organized as a centuria. Crewmen could sign on as

marines, rowers/seamen, craftsmen and various other jobs, though all personnel serving in the imperial fleet wereclassed as milites ("soldiers"), regardless of their function; only when differentiation with the army was required, were

the adjectives classiarius orclassicus added. Along with several other instances of prevalence of army terminology, thistestifies to the lower social status of the naval personnel, considered inferior to that of the auxiliaries and the

legionaries.[68]

EmperorClaudius first gave legal privileges to the navy's crewmen, enabling them to receive Romancitizenship after their period of service.

[70]This period was initially set at a minimum of 26 years (one year more than

the legions), and was later expanded to 28. Upon honorable discharge ( honesta missio), the sailors received a sizablecash payment as well.

[71]

As in the army, the ship's centuria was headed by a centurion with an optio as his deputy, while a beneficiariussupervised a small administrative staff.

[12]Among the crew were also a number ofprincipales (junior officers) and

immunes (specialists exempt from certain duties). Some of these positions, mostly administrative, were identical to

those of the army auxiliaries, while some (mostly of Greek provenance) were peculiar to the fleet. An inscription fromthe island of Cos, dated to the First Mithridatic War, provides us with a list of a ship's officers, the nautae: thegubernator(kybernts in Greek) was the helmsman or pilot, the celeusta (keleusts in Greek) supervised the rowers, aproreta (prreus in Greek) was the look-out stationed at the bow, a pentacontarchos was apparently a junior officer,

and an iatros (Lat. medicus), the ship's doctor.[72]

Each ship was commanded by a trierarchus, whose exact relationship with the ship's centurion is unclear. Squadrons,

most likely of ten ships each, were put under a nauarchus, who often appears to have risen from the ranks of thetrierarchi.

[68][73][74]The post ofnauarchus archigubernes ornauarchus princeps appeared later in the Imperial period,

and functioned either as a commander of several squadrons or as an executive officer under a civilian admiral,equivalent to the legionaryprimus pilus.

[75][76]All these were professional officers, usuallyperegrini who had a status

equal to an auxiliary centurion (and were thus increasingly called centuriones [classiarii] after ca. 70 AD).[77]

Until thereign ofAntoninus Pius, their careers were restricted to the fleet.

[12]Only in the 3rd century were these officers equated

to the legionary centurions in status and pay, and could henceforth be transferred to a similar position in the legions.[78]

High Command During the Republic, command of a fleet was given to a serving magistrate orpromagistrate, usuallyof consular or praetorian rank.

[79]In the Punic Wars for instance, one consul would usually command the fleet, and

another the army. In the subsequent wars in the Eastern Mediterranean, praetors would assume the command of thefleet. However, since these men were political appointees, the actual handling of the fleets and of separate squadrons

was entrusted to their more experienced legates and subordinates. It was therefore during the Punic Wars that theseparate position of praefectus classis ("fleet prefect") first appeared.

[80]Initially subordinate to the magistrate in

command, after the fleet's reorganization by Augustus, the praefectus classis becameprocuratorial positions in charge

of the permanent fleets. They were initially filled either from among the equestrian class, or, especially underClaudius,from the Emperor's freedmen, thus securing the Emperor's control over the fleets.

[81]From the period of the Flavian

emperors, the status of thepraefectura was raised, and only equestrians with military experience who had gone through

the militia equestri were appointed.[75][81]

Nevertheless, the prefects remained largely political appointees, and despitetheir military experience, usually in command of army auxiliary units, their knowledge of naval matters was minimal,forcing them to rely on their professional subordinates.

[71]The difference in importance of the fleets they commanded

was also reflected by the rank and the corresponding pay of the commanders. The prefects of the two praetorian fleets

were ranked procuratores ducenarii, meaning they earned 200,000 sesterces annually, the prefects of the ClassisGermanica, the Classis Britannica and later the Classis Pontica were centenarii (i.e. earning 100,000 sesterces), whilethe other fleet prefects weresexagenarii (i.e. they received 60,000 sesterces).

[82]

Ship typesFor more details on this topic, seeHellenistic-era warships.The generic Roman term for an oar-driven galley warship was "long ship" (Latin: navis longa, Greek: naus makra), asopposed to the sail-driven navis oneraria, a merchant vessel, or the minor craft (navigia minora) like thescapha.

[83]

The navy consisted of a wide variety of different classes of warships, from heavy polyremes to light raiding andscouting vessels. Unlike the rich Hellenistic Successor kingdoms in the East however, the Romans did not rely on heavywarships, with quinqueremes (Gk.pentrs), and to a lesser extent quadriremes (Gk. tetrrs) and triremes (Gk. trirs)providing the mainstay of the Roman fleets from the Punic Wars to the end of the Civil Wars.

[84]The heaviest vessel

mentioned in Roman fleets during this period was the hexareme, of which a few were used as flagships.[85]

Lightervessels such as the liburnians and the hemiolia, both swift types invented by pirates, were also adopted as scouts andlight transport vessels.

During the final confrontation between Octavian and Mark Antony, Octavian's fleet was composed of quinqueremes,together with some "sixes" and many triremes and liburnians, while Antony, who had the resources ofPtolemaic Egyptto draw upon,

[84]fielded a fleet also mostly composed of quinquiremes, but with a sizeable complement of heavier

warships, ranging from "sixes" to "tens" (Gk. dekrs).[86][87] Later historical tradition made much of the prevalence oflighter and swifter vessels in Octavian's fleet,

[88]with Vegetius even explicitly ascribing Octavian's victory to the

liburnians.[89]

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

11/53

This prominence of lighter craft in the historical narrative is perhaps best explained in light of subsequent

developments. After Actium, the operational landscape had changed: for the remainder of the Principate, no opponentexisted to challenge Roman naval hegemony, and no massed naval confrontation was likely. The tasks at hand for theRoman navy were now the policing of the Mediterranean waterways and the border rivers, suppression of piracy, and

escort duties for the grain shipments to Rome and for imperial army expeditions. Lighter ships were far better suited tothese tasks, and after the reorganization of the fleet following Actium, the largest ship kept in service was a hexareme,

the flagship of the Classis Misenensis. The bulk of the fleets was composed of the lighter triremes and liburnians (Latin:liburna, Greek: libyrnis), with the latter apparently providing the majority of the provincial fleets.

[90]In time, the term

"liburnian" came to mean "warship" in a generic sense.[22]

In addition, there were smaller oared vessels, such as the navis actuaria, with 30 oars (15 on each bank), a shipprimarily used for transport in coastal and fluvial operations, for which its shallow draught and flat keel were ideal. Inlate Antiquity, it was succeeded in this role by the navis lusoria ("playful ship"), which was extensively used for patrolsand raids by the legionary flotillas in the Rhine and Danube frontiers.Roman ships were commonly named after gods (Mars, Iuppiter, Minerva, Isis), mythological heroes (Hercules),geographical maritime features such as Rhenus or Oceanus, concepts such as Harmony, Peace, Loyalty, Victory

(Concordia,Pax,Fides, Victoria) or after important events (Dacicus for the Trajan's Dacian Wars orSalamina for theBattle of Salamis).

[91]They were distinguished by their figurehead (insigne orparasemum),

[92]and, during the Civil

Wars at least, by the paint schemes on their turrets, which varied according to each fleet.[93]

Armament and tactics In Classical Antiquity, a ship's main weapon was the ram (rostra, hence the name navis

rostrata for a warship), which was used to sink or immobilize an enemy ship by holing its hull. Its use, however,required a skilled and experienced crew and a fast and agile ship like a trireme or quinquereme. In the Hellenistic

period, the larger navies came instead to rely on greater vessels. This had several advantages: the heavier and sturdierconstruction lessened the effects of ramming, and the greater space and stability of the vessels allowed the transport notonly of more marines, but also the placement of deck-mountedballistae and catapults.

[94]Although the ram continued to

be a standard feature of all warships and ramming the standard mode of attack, these developments transformed the role

of a warship: from the old "manned missile", designed to sink enemy ships, they became mobile artillery platforms,which engaged in missile exchange andboarding actions. The Romans in particular, being initially inexperienced at seacombat, relied upon boarding actions through the use of the corvus. Although it brought them some decisive victories, it

was discontinued because it tended to unbalance the quinqueremes in high seas; two Roman fleets are recorded to havebeen lost during storms in the First Punic War.

[95]During the Civil Wars, a number of technical innovations, which are

attributed to Agrippa,[96]

took place: the harpax, a catapult-fired grappling hook, which was used to clamp onto anenemy ship, reel it in and board it, in a much more efficient way than with the old corvus, and the use of collapsible

fighting towers placed one apiece bow and stern, which were used to provide the boarders with supporting fire.[97]

Fleets

Principate period

After the end of the civil wars, Augustus reduced and reorganized the Roman armed forces, including the navy. A large part of the fleet of Mark Antony was burned, and the rest was withdrawn to a new base at Forum Iulii (modernFrjus),

[98]which remained operative until the reign of Claudius.

[99]However, the bulk of the fleet was soon subdivided

into two praetorian fleets at Misenum and Ravenna, supplemented by a growing number of minor ones in the provinces,which were often created on an ad hoc basis for specific campaigns. This organizational structure was maintainedalmost unchanged until the 4th century.2 Praetorian fleets. The two major fleets were stationed in Italy and acted as a central naval reserve, directly available

to the Emperor (hence the designation "praetorian"). In the absence of any naval threat, their duties mostly involvedpatrolling and transport duties. These were not confined to the waters around Italy, but throughout the Mediterranean.There is epigraphic evidence for the presence of sailors of the two praetorian fleets at Piraeus and Syria. These two

fleets were: The Classis Misenensis, established in 27 BC and based at Portus Julius. LaterClassis praetoria Misenesis Pia

Vindex. Detachments of the fleet served at secondary bases, such as Ostia, Puteoli, Centumcellae and otherharbors.

[100]

The Classis Ravennatis, established in 27 BC and based at Ravenna. LaterClassis praetoria Ravennatis PiaVindex.

11 Provincial fleets The various provincial fleets were smaller than the praetorian fleets and composed mostly of

lighter vessels. Nevertheless, it was these fleets that saw action, in full campaigns or raids on the periphery of theEmpire.

The Classis Africana Commodiana Herculea, established by Commodus in 186 to secure the grain shipments(annona) from North Africa to Italy,

[101]after the model of the Classis Alexandrina.

The Classis Alexandrina, based in Alexandria, it controlled the eastern part of the Mediterranean sea. It wasfounded by Caesar Augustus around 30 BC, probably from ships that fought at thebattle of Actium and manned

mostly by Greeks of theNile Delta.[102] Having supported emperorVespasian in the civil war of 69, it was awardedof the cognomenAugusta.

[102]The fleet was responsible chiefly for the escort of the grain shipments to Rome (and

later Constantinople), and also apparently operated the Nile river patrol.[103]

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

12/53

The Classis Britannica, established in 40 or 43 AD at Gesoriacum (Boulogne-sur-Mer).[104]

It participated inthe Roman invasion of Britain and the subsequent campaigns in the island.

[102]The fleet was probably based at

Rutupiae (Richborough) until 85 AD, when it was transferred to Dubris (Dover). Other bases were Portus Lemanis

(Lympne) and Anderitum (Pevensey), while Gesoriacum on the Gallic coast likely remained active.[105]

During the2nd-3rd centuries, the fleet was chiefly employed in transport of supplies and men across the English Channel. TheClassis Britannica disappears (at least under that name) from the mid-3rd century, and the sites occupied by it were

soon incorporated into the Saxon Shore system.[105]

The Classis Germanica was established in 12 BC by Drusus at Castra Vetera.

[106]It controlled the Rhine river,

and was mainly a fluvial fleet, although it also operated in the North Sea. It is noteworthy that the Romans' initiallack of experience with the tides of the ocean left Drusus' fleet stranded on the Zuyder Zee.

[107]After ca. 30 AD,

the fleet moved its main base to the castrum of Alteburg, some 4 km south of Colonia Agrippinensis (modernCologne).

[108]Later granted the honorificsAugusta Pia Fidelis Domitiana following the suppression of the Revolt

of Saturninus.[109]

The Classis nova Libyca, first mentioned in 180, based most likely at Ptolemais on the Cyrenaica.

The Classis Mauretanica, based at Caesarea Mauretaniae (modern Cherchell), it controlled the African coasts

of the western Mediterranean sea. Established on a permanent basis after the raids by the Moors in the early 170s.

The Classis Moesica was established sometime between 20 BC and 10 AD.[106]

It was based inNoviodunumand controlled the Lower Danube from the Iron Gates to the northwestern Black Sea as far as the Crimea.

[110]The

honorificFlavia, awarded to it and to the Classis pannonica, may indicate its reorganization by Vespasian.[111]

The Classis Pannonica, a fluvial fleet controlling the Upper Danube from Castra Regina in Raetia (modernRegensburg) to Singidunum in Moesia (modern Belgrade). Its exact date of establishment is unknown. Some traceit to Augustus' campaigns in Pannonia in ca. 35 BC, but it was certainly in existence by 45 AD.

[109][112]Its main

base was probably Taurunum (modern Zemun) at the confluence of the riverSava with the Danube. Under theFlavian dynasty, it received the cognomenFlavia.

[112]

The Classis Perinthia, established after the annexation ofThrace in 46 AD and based in Perinthus. Probablybased on the indigenous navy, it operated in the Propontis and the Thracian coast.

[45]Probably united with the

Classis Pontica at a later stage.

The Classis Pontica, founded in 64 AD from the Pontic royal fleet,[106][113]

and based in Trapezus, although onoccasion it was moved to Byzantium (in ca. 70),

[114]and in 170, to Cyzicus.

[115]This fleet was used to guard the

southern and eastern Black Sea, and the entrance of the Bosporus.[81]

According to the historian Josephus, in thelatter half of the 1st century, it numbered 40 warships and 3,000 men.

[116]

The Classis Syriaca, established probably underVespasian, and based in Seleucia Pieria (hence the alternativename Classis Seleucena)[117] in Syria.[103] This fleet controlled the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean sea.

In addition, there is significant archaeological evidence for naval activity by certain legions, which in all likelihood

operated their own squadrons: legio XXII Primigenia in the Upper Rhine and Main rivers, legio X Fretensis in theJordan Riverand the Sea of Galilee, and several legionary squadrons in the Danube frontier.

[118]

Dominate period Our main source for the structure of the late Roman military is the Notitia Dignitatum, whichcorresponds to the situation of the 390s for the Eastern Empire and the 420s for the Western Empire. Notable in theNotitia is the large number of smaller squadrons that have been created, most of these fluvial and of a local operationalrole.Fleets of the Danube frontier The Classis Histrica, the successor of the Classis Pannonica and the Classis Moesica

was active in the Upper Danube, with bases at Mursa in Pannonia II,[119]

Florentia in Pannonia Valeria,[120]

Arruntum inPannonia I,

[121]Viminacium in Moesia I

[122]and Aegetae in Dacia ripensis.

[123]Smaller fleets are also attested on the

tributaries of the Danube: the Classis Arlapensis et Maginensis (based at Arelape and Comagena) and the Classis

Lauriacensis(based at Lauriacum) in Pannonia I,

[121]the

Classis Stradensis et Germensis, based at Margo in Moesia

I,[122]

and the Classis Ratianensis, in Dacia ripensis.[123]

The naval units were complemented by port garrisons andmarine units, drawn from the army. In the Danube frontier these were:

In Pannonia I and Noricum ripensis, naval detachments (milites liburnarii) of the legio XIV Gemina and thelegio X Gemina at Carnuntum and Arrabonae, and of the legio IIItalica at Ioviacum.

[121]

In Pannonia II, the IFlavia Augusta (at Sirmium) and the IIFlavia are listed under their prefects.[119]

In Moesia II, two units of sailors (milites nauclarii) at Appiaria and Altinum.[124]

In Scythia Minor, marines (muscularii)[125]

of legio II Herculia at Inplateypegiis and sailors (nauclarii) at

Flaviana.[126]

Fleets in Western Europe In the West, and in particular in Gaul, several fluvial fleets had been established. Thesecame under the command of the magister peditum of the West, and were:

[127]

The Classis Anderetianorum, based at Parisii (Paris) and operating in the Seine and Oise rivers.

The Classis Ararica, based at Caballodunum (Chalon-sur-Sane) and operating in the Sane River.

A Classis barcariorum, composed of small vessels, at Eburodunum (modern Yverdon-les-Bains) at LakeNeuchtel.

The Classis Comensis at Lake Como.

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

13/53

The old praetorian fleets, the Classis Misenatis and the Classis Ravennatis are still listed, albeit with nodistinction indicating any higher importance than the other fleets.

The Classis fluminis Rhodani, based at Arelate and operating in the Rhne River. It was complemented with amarine detachment (milites muscularii) based at Marseilles.

The Classis Sambrica, based at Locus Quartensis (unknown location) and operating in the Somme Riverandthe Channel. It came under the command of the dux Beligae Secundae.

[128]

The Classis Venetum, based at Aquileia and operating in the northern Adriatic Sea. This fleet may have beenestablished to ensure communications with the imperial capitals in the Po Valley (Ravenna and Milan) and with

Dalmatia.[129]

It is notable that, with the exception of the praetorian fleets (whose retention in the list does not necessarily signify anactive status), the old fleets of the Principate are missing. The Classis Britannica vanishes under that name after themid-3rd century;

[130]its remnants were later subsumed in the Saxon Shore system. The Mauretanian and African fleets

had been disbanded or taken over by the Vandals, while the absence of the Classis Germanica is most probably due tothe collapse of the Rhine frontierafter the Crossing of the Rhine by the barbarians in winter 405-406.Fleets in the Eastern Mediterranean As far as the East is concerned, we know from legal sources that the ClassisAlexandrina[131] and the Classis Seleucena

[132]continued to operate, and that in ca. 400 a Classis Carpathia was

detached from the Syrian fleet and based at the Aegean island ofKarpathos.[133]

A fleet is known to have been stationedat Constantinople itself, but no further details are known about it.

[54]

Ports Major Roman ports were:

Misenum Classis, nearRavenna

Alexandria

Leptis Magna

Ostia

Port of Mainz (Mogontiacum, river navy on the Rhine)

See alsoMilitary of ancient Rome portal

Nemi ships

Caligula's Giant Ship

Notes

1. ^Potter 2004, pp. 7778

2. ^Meijer 1986, pp. 1471483. ^

abMeijer 1986, p. 149

4. ^Livy,AUCIX.30; XL.18,26; XLI.15. ^

abcGoldsworthy 2000, p. 96

6. ^Meijer 1986, p. 1507. ^Potter 2004, p. 768. ^

ab

Goldsworthy (2003), p. 349. ^

ab

Goldsworthy (2000), p. 9710. ^ Polybius, The Histories, I.20-2111. ^Saddington 2007, p. 20112. ^

abc

Webster & Elton (1998), p. 166

13. ^abc

Goldsworthy (2003), p. 3814. ^

abMeijer 1986, p. 167

15. ^ Gruen (1984), p. 359.16. ^Meijer 1986, pp. 16716817. ^Meijer 1986, p. 16818. ^Meijer 1986, p. 17019. ^Meijer 1986, pp. 170171

20. ^Meijer 1986, p. 17321. ^

abMeijer 1986, p. 175

22. ^abc

Connolly (1998), p. 273

23. ^Appian, The Mithridatic Wars, 9224. ^

ab

Starr (1989), p. 6225. ^Cassius Dio,Historia Romana, XXXVI.2226. ^Plutarch,Life of Pompey, 2427. ^Appian, The Mithridatic Wars, 93

28. ^ Goldsworthy (2007), p. 18629. ^Appian, The Mithridatic Wars, 94

30. ^Appian, The Mithridatic Wars, 95-96

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

14/53

31. ^ Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, III.9

32. ^ Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, III.1333. ^ Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, III.1434. ^ Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, III.15

35. ^Saddington 2007, pp. 20520636. ^Saddington 2007, p. 206

37. ^Saddington 2007, p. 20738. ^Saddington 2007, p. 208

39. ^Tacitus, The Annals II.640. ^Res Gestae, 26.441. ^ Webster & Elton (1998), pp. 160-16142. ^ Webster & Elton (1998), p. 16143. ^Tacitus, The Histories, II.1244. ^Tacitus, The Histories, II.6745. ^

ab

Webster & Elton (1998), p. 164

46. ^Tacitus, The Histories, IV.1647. ^Tacitus, The Histories, IV.7948. ^Tacitus, The Histories, V.23-25

49. ^Tacitus,Agricola, 25; 29

50. ^Tacitus,Agricola, 1051. ^Tacitus,Agricola, 24

52. ^ Lewis & Runyan (1985), p. 353. ^

ab

Lewis & Runyan (1985), p. 454. ^

abcde

Casson (1991), p. 21355. ^Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Gallienii, 13.6-7

56. ^Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Gallienii, 13.8-957. ^Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Divi Claudii, 6.2-4; 8.158. ^Zosimus,Historia Nova, I.42-45

59. ^Eutropius,Breviarium, IX.2160. ^Panegyrici Latini, 8.661. ^Panegyrici Latini, 8.1262. ^Panegyrici Latini, 6.5; 8.6-8

63. ^Eutropius,Breviarium9.22; Aurelius Victor,Book of Caesars39.4264. ^ Treadgold (1997), p. 14565. ^

ab

MacGeorge (2002), pp. 306-307

66. ^ Lewis & Runyan (1985), pp. 4-867. ^ MacGeorge (2002), p. 30768. ^

abcd

Casson (1991), p. 188

69. ^ Starr (1960), p. 75 Table 170. ^Saddington 2007, p. 21271. ^

abGardiner 2000, p. 80

72. ^Saddington 2007, pp. 201202

73. ^ Starr (1960), p. 3974. ^ Webster & Elton (1998), pp. 165-16675. ^

abSaddington 2007, p. 210

76. ^ Starr (1960), pp. 42-4377. ^Saddington 2007, pp. 21021178. ^ Wesch-Klein (1998), p. 25

79. ^ Rodgers (1976), p. 6080. ^Livy,AUCXXVI.48; XXXVI.4281. ^

abc

Webster & Elton (1998), p. 16582. ^Pflaum, H.G. (1950).Les procurateurs questres sous le Haut-Empire romain, pp. 50-5383. ^Saddington 2007, pp. 20220384. ^

abPotter 2004, p. 77

85. ^Gardiner 2000, p. 70

86. ^Cassius Dio,Historia Romana, L.23.287. ^Gardiner 2000, pp. 70, 7788. ^Plutarch,Antony, 62

89. ^Vegetius,De Re Militari, IV.3390. ^ Casson (1995), p. 14191. ^ Casson (1995), pp. 357-358; Casson (1991), pp. 190-19192. ^Saddington 2007, p. 203

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

15/53

93. ^ Warry (2004), p. 183

94. ^ Warry (2004), p. 9895. ^ Warry (2004), p. 11896. ^Appian, The Civil Wars, V.106 & V.118

97. ^ Warry (2004), pp. 18218398. ^Tacitus, The Annals, IV.5; Strabo, Geography, IV.1.9

99. ^Gardiner 2000, p. 78100. ^ Webster & Elton (1998), p. 158

101. ^Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Commodi, 17.7102. ^

abc

Webster & Elton (1998), p. 159103. ^

abSaddington 2007, p. 215

104. ^ Cleere (1977), pp. 16; 18-19105. ^

ab

Cleere (1977), p. 19106. ^

abc

Cleere (1977), p. 16107. ^ Webster & Elton (1998), p. 160

108. ^Kln-Alteburg at livius.org109. ^

ab

Webster & Elton (1998), p. 162110. ^ Webster & Elton (1998), pp. 162-165

111. ^ Webster & Elton (1998), p. 163

112. ^a

b

Saddington 2007, p. 214113. ^ Starr (1989), p. 76

114. ^Tacitus, The Histories, II.83; III.47115. ^ Starr (1989), p. 77116. ^Josephus, The Jewish War, II.16.4117. ^Codex Theodosianus, X.23.1

118. ^Rmisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz: The Fleets and Roman Border Policy119. ^

abNotitia Dignitatum,Pars Occ., XXXII.

120. ^Notitia Dignitatum,Pars Occ., XXXIII.

121. ^abcNotitia Dignitatum,Pars Occ., XXXIV.

122. ^abNotitia Dignitatum,Pars Orient., XLI.

123. ^abNotitia Dignitatum,Pars Orient., XLII.

124. ^Notitia Dignitatum,Pars Orient., XL.

125. ^musculus (meaning "small mouse") was a kind of small ship126. ^Notitia Dignitatum,Pars Orient., XXXIX.127. ^Notitia Dignitatum,Pars Occ., XLII.

128. ^Notitia Dignitatum,Pars Occ., XXXVIII.129. ^ Lewis & Runyan (1985), p. 6130. ^Classis Britannica at RomanBritain.org

131. ^Codex Justinianus, XI.2.4132. ^Codex Justinianus, XI.13.1133. ^Codex Theodosianus, XIII.5.32

References

Casson, Lionel (1991), The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient

Times, Princeton University Press, ISBN978-0691014777, http://books.google.com/?id=4Ls6MczXvBEC

Casson, Lionel (1995), Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN

0801851300 Cleere, Henry (1977), "The Classis Britannica" (PDF), CBA Research Report (18): 1619,

http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/cbaresrep/pdf/018/01804001.pdf, retrieved 2008-10-11

Connolly, Peter (1998), Greece and Rome at War, Greenhill

Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) (2004), AGE OF THE GALLEY: Mediterranean Oared Vessels since pre-Classical

Times, Conway Maritime Press, ISBN978-0851779553

Goldsworthy, Adrian (2000), The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265146 BC, Cassell, ISBN 0-304-36642-0

Goldsworthy, Adrian (2003), The Complete Roman Army, Thames & Hudson Ltd., ISBN0-500-05124-0

Goldsworthy, Adrian (2007), "A Roman Alexander: Pompey the Great", In the name of Rome: The men whowon the Roman Empire, Phoenix, ISBN978-0-7538-1789-6

Gruen, Erich S. (1984), The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome: Volume II, University of California

Press, ISBN0-520-04569-6 Lewis, Archibald Ross; Runyan, Timothy J. (1985),European Naval and Maritime History, 300-1500, Indiana

University Press, ISBN0253205735

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

16/53

MacGeorge, Penny (2002), "Appendix: Naval Power in the Fifth Century", Late Roman Warlords, OxfordUniversity Press, ISBN978-0199252442

Meijer, Fik (1986),A History of Seafaring in the Classical World, Routledge, ISBN978-0709935650

Potter, David (2004), "The Roman Army and Navy", in Flower, Harriet I., The Cambridge Companion to theRoman Republic, Cambridge University Press, pp. 6688, ISBN978-0521003902

Rodgers, William L. (1967), Naval Warfare Under Oars, 4th to 16th Centuries: A Study of Strategy, Tactics

and Ship Design, Naval Institute Press, ISBN978-0870214875 (German) Rost, Georg Alexander (1968), Vom Seewesen und Seehandel in der Antike, John Benjamins

Publishing Company, ISBN9060323610

Saddington, D.B. (2007), "Classes. The Evolution of the Roman Imperial Fleets", in Erdkamp, Paul, ACompanion to the Roman Army, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., ISBN978-1-4051-2153-8

Starr, Chester G. (1960), The Roman Imperial Navy: 31 B.C.-A.D. 324 (2nd Edition), Cornell University Press

Starr, Chester G. (1989), The Influence of Sea Power on Ancient History, Oxford University Press US, ISBN978-0195056679

Treadgold, Warren T. (1997), A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford University Press, ISBN0804726302

Warry, John (2004), Warfare in the Classical World, Salamander Books Ltd., ISBN0-8061-2794-5

Webster, Graham; Elton, Hugh (1998), The Roman Imperial Army of the First and Second Centuries A.D.,

University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN0806130002

(German) Wesch-Klein, Gabriele (1998), Soziale Aspekte des rmischen Heerwesens in der Kaiserzeit, Franz

Steiner Verlag, ISBN3515073000

Workman-Davies, Bradley (2006), Corvus: A Review of the Design and Use of the Roman Boarding Bridge During the First Punic War 264 -241 B.C., Lulu.com, ISBN 978-1847288820,http://books.google.com/?id=V5TZSAVLIMcC

External links

(Italian)The Imperial fleet of Misenum

The Classis Britannica

The Roman Fleet,Roman-Empire.net

The Roman Navy: Masters of the Mediterranean,HistoryNet.com

Galleria Navale onNavigare Necesse Est

Port of Claudius, the museum of Roman merchant ships found in Fiumicino (Rome)

Diana Nemorensis, Caligula's ships in the lake of Nemi. Rmisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz: The Fleets and Roman Border Policy

Forum Navis Romana

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

17/53

Three-banked ("trireme") Roman quinquereme with the corvus boarding bridge. The use of the corvus negated the

superior Carthaginian naval expertise, and allowed the Romans to establish their naval superiority in the westernMediterranean

Roman as coin of the second half of the 3rd century BC, featuring the prow of a galley, most likely a quinquereme.

Several similar issues are known, illustrating the importance of naval power during that period of Rome's history

A Roman octeris of the 3rd century BCE

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

18/53

A Roman triremis of the 2nd century BCE

An enneris, one of the larger ships of the Roman fleet, 1st century BCE

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

19/53

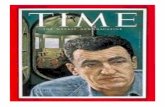

Pompey the Great. His swift and decisive campaign against the pirates re-established Rome's control overthe Mediterranean sea lanes

Vivid view of the Battle of Actium in this reconstructional illustration of an enneris (a large type of battlegalley, used by Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra)

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

20/53

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

21/53

A quadriremis, another ship of the combined Roman-Egyptian fleet during the Battle of Actium

A triremis, part of the Roman-Egyptian fleet of Antony and Cleopatra, Battle of Actium

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

22/53

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

23/53

Adromo of the West Roman kingdom under Germanic rulers, CE 526

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

24/53

An East Roman penteconteris, featuring already the divided stern which was so typical for the later

byzantine dromons

Roman warship on a Mark Antony denarius

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

25/53

Model of a Roman bireme

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

26/53

Reconstruction of a late Roman navis lusoria at Mainz.

Two-banked lburnians of the Danube fleets during Trajan's Dacian Wars. Casts of reliefs from Trajan's Column, Rome.

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

27/53

Ballistae on a Roman ship

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Pages in category "Ancient Roman admirals"

The following 15 pages are in this category, out of 15 total. This list may not reflect recent changes

A

Marcius Agrippa Lucius Arruntius

Marcus Atilius Regulus

B

Bonosus (usurper)

D

Gaius Duilius

L

Marcus Lurius Gaius Lutatius Catulus

M

Menas (admiral)

P

Papias (admiral)

Pliny the Elder

R

Lucius Aemilius Regillus

S

Gaius Livius Salinator

Gnaeus Servilius Geminus

Titus Statilius Taurus

V

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

28/53

Naval tactics in the Age of Galleys

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaNaval tactics in the age of galleys were used from antiquity to the early 17th century when sailing ships replaced oaredgalleys.

Weapons in the age of galleys Throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages until the 16th century, the weapons relied onwere:

the ship itself, used as abattering ram,

the swords of the crew,

missile weapons such as bolts from heavy crossbows fixed on the bulwarks, bows and arrows, weights droppedfrom a yard or pole rigged out, and the various means of setting an enemy alight; by shooting arrows withburning tow or by Greek fire or wild fire, blown through tubes (cannae, whence "cannon").

The nature ofGreek fire is still an unsettled question, and it is believed by some authorities that the Byzantines of theMiddle Ages were acquainted with the use of gun-powder. However, it is certain that even after the introduction ofartillery in the 14th century, they were very feeble.Early naval tactics All actions were fought at close quarters, where ramming andboarding were possible. But the useof the ram was only available for a vessel driven by oars. A sailing vessel could not ram unless she were running beforea good breeze. In a light wind her charge would be ineffective, and it could not be made at all from leeward. Therefore,

while fleets depended on the methods ofbattle at close quarters, two conditions were imposed on the warship: she must be small and light, so that her crew could row her with effect, and

she must carry a numerous crew to work her oars and board or repel boarders.Sails were used by the triremes and other classes of warship, ancient and medieval, when going from point to point to

relieve the rowers from absolutely exhausting toil. They were lowered in action, and when the combatant had a secureport at hand, they were left ashore before battle.These conditions applied alike to Phormio, the Athenian admiral of the 5th century BC, to the Norse king OlafTryggvason of the 10th century AD, and to the chiefs of the Christian and Turkish fleets which fought the battle ofLepanto in AD 1571. There might be, and were, differences of degree in the use made of oar and sail respectively.Outside the Mediterranean, the sea was unfavourable to the long, narrow and light galley of 120 ft. long and 20 ft. ofbeam. But the Norse ship found at Gokstad, though her beam is a third of her length, and she is well adapted for rough

seas, is also a light and shallow craft, to be easily rowed or hauled up on a beach.Some medieval vessels were ofconsiderable size, but these were the exception; they were awkward, and were rather transports than warships. Given awarship which is of moderate size and crowded with men, it follows that prolonged cruises, and blockade in the fullsense of the word, were beyond the power of the sea commanders ofantiquity and the Middle Ages. There were shipsused for trade which with a favourable wind could rely on making six knots. But a war fleet could not provide thecover, or carry the water and food, needed to keep the crews efficient during a long cruise. So long as galleys wereused, that is to say, till the middle of the 18th century, they were kept in port as much as possible, and a tent was rigged

over the deck to house the rowers. The fleet was compelled to hug the shore in order to find supplies. It alwaysendeavoured to secure a basis on shore to store provisions and rest the crews. Therefore the wider operations wereslowly made. Therefore too, when the enemy was to be waited for, or a port watched, some point on shore was secured

and the ships were drawn up. It was by holding such a point that the Corinthian allies of the Syracusans were able to pinin the Athenians. The Romans watched Lilybeum in the same way, and Hannibal the Rhodian could run the blockade before they were launched and ready to stop him. The Norsemen hauled their ships on shore, stockaded them andmarched inland. The Greeks ofHomerhad done the same and could do nothing else. Ruggiero di Lauria, in AD 1285,waited at the Hormigas with his galleys on the beach till the French were seen to be coming past him. Edward III. InAD 1350, stayed at Winchelsea till the Spaniards were sighted. The allies at Lepanto remained at anchor nearDragonera till the last moment.Line abreast Given that the fighting was at close quarters with ram, stroke of sword, crossbow bolt, arrow, pigs of ironor lead and wild fire blown through tubes, it follows that the formations and tactics were equally imposed on thecombatants. The formation was inevitably the line abreast the ships going side by side for the object was to bring allthe rams, or all the boarders into action at once. It was quite as necessary to strike with the prow when boarding as whenramming. If the vessels were laid side by side the oars would have prevented them from touching.Ramming The extent to which ramming or boarding would be used respectively would depend on the skill of therowers. The highly trained Athenian crews of the early Peloponnesian War relied mainly on the ram. They aimed at

Ancient dashing through an enemy's line, and shaving off the oars from one side of an opponent. When successfullypractised, this maneuver would be equivalent to the dismasting of a sailing line of battle ship. It enabled the assailant toturn, and ram his crippled enemy in the stern. But an attack with the ram might be exceedingly dangerous to the

assailant, if he were not very solidly built. His ram might be broken off in the shock. The Athenians found this a veryreal peril, and were compelled to construct their triremes with stronger bows, to contend with the more heavily builtPeloponnesian vessels whereby they lost much of their mobility. In fact success in ramming depended so much on acombination of skill and good fortune that it played a somewhat subordinate part in most ancient sea fights. The

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

29/53

Romans baffled the ramming tactics of the Carthaginians by the invention of the corva or crow, a plank with a spike for

hooking onto enemy ships which grappled the prow of the rammer, and provided a gangway for boarders. It's notcertain whether this weapon destabilized ships and led to whole fleets being lost in storms. The Romans did continuetheir boarding tactics in the naval battles of the Punic Wars, but are also reported as ramming the Carthiginian vessels

after the abandonment of the corvus. An older and alternative way for boarding was the use of grappling hooks andplanks, also a more flexible system than the corvus. Agrippa introduced a weapon with a function similar to the corvus,

the harpax.The introduction of guns After the introduction of artillery in the 14th century, when guns were carried in the bows of

the galley, it was considered bad management to fire them until the prow was actually touching the enemy. If they weredischarged before the shock there was always a risk that they would be fired too soon, and the guns of the time couldnot be rapidly reloaded. The officer-like course was to keep the fire for the last moment, and use it to clear the way forthe boarders. As a defense against boarding, the ships of a weaker fleet were sometimes tied side to one another, in theMiddle Ages, and a barrier made with oars and spars. But this defensive arrangement, which was adopted by OlafTryggvason of Norway at Swolder (AD 1000), and by the French at Sluys (AD 1340), could be turned by an enemywho attacked on the flank. To meet the shock of ramming and to ram, medieval ships were sometimes "bearded", i.e.

fortified with iron bands across the bows. The principles of naval warfare known to the ancient world descendedthrough Byzantium to the Italian Republics and from them to the West.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911).Encyclopdia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Classis Misenensis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaThe classis Misenensis ("Fleet ofMisenum"), later awarded the honorifics praetoria and Pia Vindex, was the seniorfleet of the imperial Roman Navy.History The classis Misenensis was founded by Caesar Augustus in 27 BC, when the fleet of Italy, until then basedmostly at Ostia, was moved to the new harbour ofPortus Julius at Misenum in the Bay of Naples.

[1]It was commanded

by apraefectus classis, drawn from the highest levels of the equestrian class, those earning more than 200,000 sestercesa year. Its mission was to control the western part of the Mediterranean Sea, and, as the honorificpraetoria, awarded byVespasian for its support during the civil warof AD 69,[2] suggests, the classis Misenensis, together with the classisRavennatis, formed the naval counterpart of the Praetorian Guard, a permanent naval force at the emperor's directdisposal.The classis Misenensis recruited its crews mostly from the East, especially from Egypt.

[2]Since Rome did not

face any naval threat in the Mediterranean, the bulk of the fleet's crews was idle. Some of the sailors were based inRome itself, initially housed in the barracks of the Praetorian Guard, but later given their own barracks, the Castra

Misenatium near the Colosseum.[1]

There they were used to stage mock naval battles (naumachiae), and operated the

mechanism that deployed the canvas canopy of the Colosseum.[3]

Among the sailors of this fleet,Nero levied the legio IClassis, and used some of its leading officers in the murder of his mother Agrippina the Younger.

[1]In 192, the

Misenum fleet supported Didius Julianus, and then participated in the campaign of Septimius Severus againstPescennius Niger, transporting his legions to the East.

[4]The fleet remained active in the East for the next few decades,

where the emergence of the Persian Sassanid Empire posed a new threat. In 258260, the classis Misenensis wasemployed in the suppression of a rebellion in North Africa.

[5]In 324 the fleet's ships participated in the campaign of

Constantine the Great against Licinius and his decisive naval victory in the Battle of the Hellespont. Afterwards, the

bulk of the ships were moved to Constantinople, where emperor Constantine had moved the capital of the RomanEmpire.List of known ships The following ship names and types of the classis Misenensis have survived:[1]

1 hexeres: Ops

1 quinquereme: Victoria

9 quadriremes:Fides, Vesta, Venus, Minerva,Dacicus,Fortuna,Annona,Libertas, Olivus

50 triremes: Concordia, Spes, Mercurius,Iuno,Neptunus,Asclepius,Hercules,Lucifer,Diana,Apollo, Venus,Perseus, Salus, Athenonix, Satyra, Rhenus, Libertas, Tigris, Oceanus, Cupidus, Victoria, Taurus, Augustus,Minerva, Particus, Eufrates, Vesta, Aesculapius, Pietas, Fides, Danubius, Ceres, Tibur, Pollux, Mars, Salvia,Triunphus,Aquila,Liberus Pater,Nilus, Caprus, Sol,Isis,Providentia,Fortuna,Iuppiter, Virtus, Castor

11 liburnians: Aquila, Agathopus, Fides, Aesculapius, Iustitia, Virtus, Taurus Ruber, Nereis, Clementia,Armata, Minerva

By 79 this fleet had probably nothing larger than a quadrireme in service,[6]

forPliny the Elder, commander of the fleet,investigated the eruption of Vesuvius in a quadrireme, presumably his flagship and the largest class of vessel in thefleet.

References

-

8/6/2019 Roman Navy Wikipedia 2011

30/53

1. ^abcA Companion to the Roman Army, p. 209

2. ^abAge of the Galley, p. 80

3. ^Historia Augusta, Commodus XV.64. ^Age of the Galley, p. 83

5. ^Age of the Galley, p. 846. ^ Pliny the Younger,Letters, VI.16

Sources Erdkamp, Paul (ed.) (2007).A Companion to the Roman Army. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.. ISBN978-1-4051-

2153-8.

Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) (2004). AGE OF THE GALLEY: Mediterranean Oared Vessels since pre-ClassicalTimes. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN978-0851779553.

Classis Ravennatis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The classis Ravennas ("Fleet ofRavenna"), later awarded the honorifics praetoria andPia Vindex, was thesecond most senior fleet of the imperial Roman Navy after the classis Misenensis. Ravenna had been used

for ship construction and as a naval port at least since the Roman civil wars, but the permanent classisRavennas was established by Caesar Augustus in 27 BC. It was commanded by a praefectus classis, drawnfrom the highest ranks of the equestrian class, those earning more than 200,000 sesterces a year, and its