Ludovico Ariosto 1474-1533 a cura del prof. Marco Migliardi .

Organo ufficiale 91della Camera di Commercio di Milano 4.pdfPARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi...

Transcript of Organo ufficiale 91della Camera di Commercio di Milano 4.pdfPARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi...

ANNO

Organo ufficialedella Divisione SSOG di InnovhubStazioni Sperimentali per l’industriaAzienda Specialedella Camera di Commercio di Milano

91RISG

LA

RIVISTAITALIANA

DELL

SOSTANZEGRASSE

E

2014

OTTOBRE/DICEMBRE 2014ISSN 0035-6808 RISGARD 91 (4) 209-284 (2014)Poste Italiane S.p.a. - Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale - 70%Finito di stampare nel mese di Marzo 2015

4

Redazione: [email protected] web: www.innovhub-ssi.it

100,00 200,00umero singolo 30,00

ORGANO UFFICIALE DELLA DIVISIONE SSOG DI INNOVHUB

STAZIONI SPERIMENTALI PER L’INDUSTRIA

AZIENDA SPECIALE DELLA CAMERA DI COMMERCIO DI MILANO

E–mail: [email protected] – Sito web: www.ssog.it

100,00 200,00umero singolo 30,00

ORGANO UFFICIALE DELLA DIVISIONE SSOG DI INNOVHUB STAZIONI SPERIMENTALI PER L’INDUSTRIA

AZIENDA SPECIALE DELLA CAMERA DI COMMERCIO DI MILANO

SSOG_1_ok:Layout 1 22-02-2013 9:01 Pagina 1

direttore responsabile: M. Surdiredazione: F. paparella

GraFiCa, iMpaGinazione e staMpa

Grafiche parole Nuove srlVia Garibaldi 58 - Brugherio

4duemilaquattordiciOTTOBRE/DICEMBRE 2014 - ANNO XCI

abbonaMenti e arretrati

[email protected]. 02/70649732Fax: 02/2665380

Sommario

M. Sala, F. Taormina, R. Maina, P. Ruggeri

211 Nota tecnica. Lubrificanti. Corrispondenze tra metodi analitici. (gennaio-dicembre 2014)

A.M. Giuffrè 221 Variation in triacylglycerols of olive oils produced in Calabria (Southern Italy) during olive ripening

C. Guillaume, Ch. Gertz, L. Ravetti

241 Pyropheophytin a and 1,2 di-acyl-glycerols in natural olive oils under different storage conditions over time

B. Matthäus, M.M. Özcan,F. AL Juhaimic,

255 Some physico-chemical properties and composition in wild olive (Olea europaea L. subsp. oleaster) fruit and oil

J.S. Amaral, S. Soares, I. Mafra, M. Beatriz PP Oliveira

261 Assessing the variability of the fatty acid profile and cholesterol content of meat sausages

Notiziario 273

Comitato di redazione

P. BONDIOLI settore tecnologie olearie e oleochimiche

L. FOLEGATTI settore sostanze grasse e proteine vegetali

S. TAGLIABUE settore cosmetica

G. GASPERINI settore prodotti vernicianti

P. ROVELLINI settore qualità/genuinità (micronutrienti e sicurezza

alimentare)

D. MARIANI settore detersivi e tensioattivi

M. SALA settore lubrificanti

Comitato di Referee

R. APARICIO Istituto de la Grasa y sus Derivados – Siviglia (E)

E. CHRISTOPOULOU Hellenic Republic Ministry of Finance – G.S. of

Consumer – Directorate Technical Control – Atene (Gr)

G. CONTARINI Istituto Lattiero Caseario - Lodi

L. CONTE Dipartimento di Scienza degli Alimenti – Università di Udine

G. DONATI Istituto Superiore Sanità – Roma

A. FABERI Ministero delle Politiche Agricole Alimentari e Forestali – Roma

H.J. FIEBIG Federal Research Centre for Nutrition and Food – Institute for Lipid

Research – Münster (D)

C. GIGLIOTTI Dipartimento di Scienze Biomediche e Biotecnologiche –

Università di Brescia

K. GROB Kantonales Laboratorium – Zurigo (CH)

F. LACOSTE Institut des Corps Gras – ITERG – Pessac (F)

G. LERCKER Dipartimento di Scienze Alimentari – Università di Bologna

L. MANNINA Facoltà di Agraria – Università degli Studi di Campobasso

R. SACCHI Dipartimento Scienze Alimentari – Università Federico II – Portici

(NA)

C. SCESA Corso di Laurea in Tecniche Erboristiche – Facoltà di Farmacia –

Università di Urbino

M. SERVILI Dipartimento di Scienze Economico-Estimative e degli Alimenti –

Università di Perugia

L. SISTI Henkel – Divisione Tensioattivi – Lomazzo (CO)

E. TISCORNIA Genova

Ö. TOKUŞOĞLU Celal Bayar University - Engineering Faculty – Manisa Turkey

Indexed and Abstracted in:• Thomson Scientific Service: Science Citation Index Expanded

(SciSearch), Journal Citation/Science Edition, Current Contents/Clinical Medicine

• Chemical Abstracts• Elsevier Bibliographic Databases: SCOPUS• FSTA – Food Science and Technology Abstract (IFIS Publishing – UK)

IMPACT FACTOR 2009: 0,340

La RIVISTA ITALIANA DELLE SOSTANZE GRASSEè l’organo ufficiale della Divisione SSOG di Innovhub

- Stazioni Sperimentali per l’Industria - Azienda Speciale della Camera di Commercio di Milano. Ha

periodicità trimestrale e la scientificità dei contenuti è garantita da un Comitato Internazionale di Referee.

Pubblica lavori originali e sperimentali di autori italiani ed esteri riguardanti la chimica, la biochimica,

l’analisi e la tecnologia nei settori: sostanze grasse e loro derivati, tensioattivi, detersivi, cosmetici, oli

minerali. Pubblica un Notiziario con informazioni su congressi,

notizie in breve e libri.La Rivista viene distribuita e consultata in Italia dalle

industrie produttrici ed esportatrici di oli e grassi alimentari ed industriali, dalle industrie chimiche, da laboratori di enti statali, da istituti di ricerca e facoltà

universitarie, da dove provengono diversi lavori scientifici.

È inoltre distribuita all’estero in vari Paesi come Spagna, Principato di Monaco, Canada, Paesi

Bassi, Svizzera, Slovenia, Regno Unito, Turchia, Lussemburgo, Malaysia, Grecia, Francia, Germania, Tunisia, Nigeria, Congo, Polonia, Romania, Bulgaria,

Russia, Stati Uniti, Brasile, Cina, Giappone.

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

211

M. Sala1*F. Taormina1

R. Maina2

P. Ruggeri3

1Divisione INNOVHUB - SSIAzienda Speciale della

Camera di Commercio di MilanoDivisione SSOG – Milano

2Sea Marconi Technologies s.a.sTorino

3ENI SpA – Refining & MarketingMilano

*CORRISPONDENZA AUTOREE-mail: [email protected]

nota tecnicalubrificanti

Corrispondenze tra metodi analitici

(gennaio-dicembre 2014)

Da diversi anni viene pubblicata una guida, a disposizione di chi lavora nel settore dei lubrificanti, in cui sono riportati i controlli maggiormente utilizzati per la caratterizzazione dei prodotti petroliferi e lubrificanti e i relativi metodi di analisi pubblicati da Enti Nazionali ed Internazionali (UNI, CEI, ASTM, IP, ISO, IEC, EN).Quest’anno è stata fatta la revisione della tabella con un aggiornamento di tutti i metodi pubblicati da gennaio a dicembre 2014.La struttura base della tabella non è stata modificata rispetto alla versione precedente: nella prima colonna si riporta il parametro analitico, cui corrispondono i numeri di norma/metodo riportati nelle colonne successive.I riferimenti normativi sono sempre divisi in quattro classi: EN - ISO - IEC; Metodi Italiani (UNI - UNI EN - UNI EN ISO - CEI – NOM); IP; ASTM.Tutti i metodi che durante l’anno hanno avuto revisioni o modifiche sono evidenziati con lo sfondo grigio.La nuova versione dei metodi ASTM è stata confrontata con l’edizione precedente e nel foglio “Commento alle nuove revisioni” si riportano i risultati di tale confronto. Quando compare la dizione “equivalenti” significa che c’è una perfetta rispondenza tra le metodiche; differenze non sostanziali tra i vari metodi sono riassunte nell’espressione “tecnicamente equivalenti”; per i metodi in cui è stata riscontrata anche una sola, ma significativa differenza, viene riportata l’espressione “non equivalenti”. Per i metodi IP si rimanda al sito http://ein.powerweb.co.uk/cssiptmqbe.htm dove è disponibile l’elenco aggiornato dei metodi e un loro confronto con i metodi ASTM e ISO.Preso atto della velocità di cambiamento dei metodi in ambito normativo, soprattutto dei metodi ASTM, si ricorda che la presente guida, non potendo essere aggiornata in tempo reale, ma facendo riferimento ad una valutazione temporale pari a un anno solare, ha delle lacune, insite proprio nella modalità in cui è stato concepito il lavoro di revisione. Per questo motivo alcuni metodi ASTM hanno come data di revisione il 2013, anche se l’ultima ricerca condotta a Dicembre 2014 non li citava come metodi in revisione.

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

212

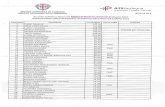

TABELLA LUBRIFICANTI (GENNAIO - DICEMBRE 2014) CORRISPONDENZA TRA METODI ANALITICI

PARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi Italiani IP ASTM D

ACQUA IN LIQUIDI ISOLANTI (KF) 60814:1997 CEI EN 60814:1998 1533-12

ACQUA IN PRODOTTI PETROLIFERI (KF) 12937:2000 6304-07

ACQUA NEGLI ANTIFREEZES CONCENTRATI (KF) 1123-99 (2009)

ACQUA PER DISTILLAZIONE 95-13e1

ACQUA NEGLI OLI ISOLANTI NELLA CARTA E NEL CARTONE IMPREGNATI OLIO

60814:1997 CEI EN 60814:1998

ADDITIVI ANTIOSSIDANTI SPECIFICI NEGLI OLI ISOLANTI

60666:2010 CEI EN 60666:2011

ALCALINITÀ DI RISERVA PER ANTICONGELANTI E ANTIRUGGINI

1121-11

ALTERABILITÀ DI OLI ISOLANTI7624:1997

60962:1988CEI 10-8:1997

ANALISI DI GRASSI LUBRIFICANTI 2269-10

ASSORBIMENTO UV DI PRODOTTI PETROLIFERI

2008-12

AZOTO (CHEMILUMINESCENZA) 4629-12

AZOTO (KJELDAHL MODIFICATO) 3228-08 (2014)

BENZINA IN LUBRIFICANTI USATI (GC) 3525-04 (2010)

CAMPIONAMENTO DI GAS IN OLIO 60567:2011 CEI EN 60567:2012

CARATTERISTICHE ANTIRUGGINE 665-14

CENERI DA PRODOTTI PETROLIFERI 482-13

CENERI NEGLI ANTICONGELANTI E ANTIRUGGINI 1119-05 (2009)

CENERI SOLFATATE3987:2010/cor 1:2011 UNI 20021:1989 163/12 874-13a

CLASSIFICAZIONE DI LIQUIDI ISOLANTI IN BASE AL PUNTO DI COMBUSTIONE E P.C. INFERIORE

61100:1992 CEI EN 61100:1997

CLASSIFICAZIONE GENERALE DI LIQUIDI ISOLANTI 61039:2008 CEI EN61039:2009

CLORO NEGLI OLI GREZZI 4929-07 (2014)

CLORO NEGLI OLI USATI NOM 161:2007

CLORO (METODO DI DECOMPOSIZIONE AD ALTA PRESSIONE)

808-11

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

213

PARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi Italiani IP ASTM D

CLORO IONICO O IDROLIZZABILE (IN ASKAREL) 60588:1979 CEI 10-6:1997

COLORE A S T M 2049:1996 UNI 20026:1989 196/97(14) 1500-12

COLORE (METODO AUTOMATICO “TRISTIMOLO”) 6045-12

COLORE SAYBOLT 156-12

COLORE APHA HAZEN (per ASKAREL) 60588:1979 CEI 10-6:1997

CONTAMINAZIONE IN DISTILLATI MEDI 12662:2008

CONTAMINAZIONE DA PARTICELLE SOLIDE 4406:1999

CONTENUTO DI OLIO NELLE PARAFFINE 2908:1974 721-06 (2011)

COPPIA DI SPUNTO E ROTOLAMENTO GRASSI (A BASSA TEMPERATURA)

1478-11

CORROSIONE DI GRASSI CON LASTRINA DI RAME UNI 20035:1992 4048-10

CORROSIONE RAME CON LAMINA 2160:1998 UNI EN ISO 2160:2001 154/00 (13) 130-12

DEMULSIVITÀ DI OLI 2711-11

DEMULSIVITÀ DI OLI MINERALI E SINTETICI 6614:1994 UNI ISO 6614:2001 1401-12

DENSITÀ (DENSIMETRO DIGITALE)12185:1996/cor 1:2001 365/97(04) 4052-11

DENSITÀ, MASSA VOLUMICA 3675:1998 UNI EN ISO 3675:2002 160/99 1298-12b

DENSITÀ O DENSITÀ RELATIVA DI LIQUIDI REFRIGERANTI

1122-13

DETERMINAZIONE DELLE CARATTERISTICHE DI OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI INIBITI E FLUIDI – TOST TESTParte 1 – Oli MineraliParte 2 – Fluidi idraulici HFCParte 3 – Procedura anidra per fluidi idraulici sinteticiParte 4 – Oli per cambi industriali

4263-1:20034263-2:20034263-3:2010

4263-4:2006

UNI EN ISO 4263-1:2005UNI EN ISO 4263-2:2005UNI EN ISO 4263-3:2010

UNI EN ISO 4263-4:2006

DILAVAMENTO CON ACQUA DI GRASSI UNI 20055:1993 1264-12

DILUIZIONE BENZINA DI OLIO USATO(DISTILLAZIONE )

UNI 20046:1992 322-97 (2012)

DISTILLAZIONE ATMOSFERICA 3405:2011 86-12

DISTILLAZIONE SOTTO VUOTO 1160-13

ELEMENTI DI ADDITIVAZIONE, METALLI DI USURA E CONTAMINANTI IN OLI LUBRIFICANTI USATI E OLI BASE (ICP-AES)

5185-13e1

ELEMENTI DI USURA E CONTAMINANTI IN OLI LUBRIFICANTI USATI O FLUIDI IDRAULICI USATI

6595-00 (2011)

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

214

PARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi Italiani IP ASTM D

ELEMENTI DI ADDITIVAZIONE IN OLI LUBRIFICANTI (ICP-AES)

4951-14

ELEMENTI, Ba-Ca-S-P-Zn IN OLI LUBRIFICANTI (FLUORESCENZA RAGGI X)

4927-10

ELEMENTI, Ba-Ca-Zn-Mg IN LUBRIFICANTI NUOVI (A.A.)

4628-05 (2011)e1

FATTORE DI DISSIPAZIONE DI LIQUIDI ISOLANTI

60247:2004 CEI EN 60247:2004

FOSFORO IN LUBRIFICANTI ED ADDITIVI(OSSIDAZIONE )

1091-11

FOSFORO IN OLI E ADDITIVI (CHINOLINA FOSFOMOLIBDATO )

4265:1986 UNI 20056:1993 149/93(03) 4047-13

GAS DISCIOLTI NELL’OLIO DI TRASFORMATORI (INTERPRETAZIONE ANALISI)

60599:1999 60599/A1:2007

CEI EN 60599:2000 CEI EN 60599/A1:2008

GASOLIO IN LUBRIFICANTI USATI (GC) 3524-14

GUIDA CONTROLLO E TRATTAMENTO OLIMINERALI ISOLANTI IN SERVIZIO IN TRASFORMAZIONE

60422:2013 CEI EN 60422:2014

INDICE DI RIFRAZIONE 5661:1983 1218-12

INDICE VISCOSITÀ, CALCOLO 2909:2002 UNI ISO 2909:2001 226/04 (14) 2270-10e1

INSOLFONABILE, RESIDUO 483-04 (2014)

INSOLUBILI IN OLI USATI 893-14

INSOLUBILI IN PENTANO 4055-04 (2013)

INVECCHIAMENTO E VALUTAZIONE CONRADSON 6617:1994 UNI 20007:1989

MISCIBILITÀ OLI 2 TEMPI 4682-13

MONITORAGGIO DI LUBRIFICANTI IN ESERCIZIO CON TECNICA FT-IR

ASTM E 2412-10

MONITORAGGIO DI OLI MINERALI PER TURBINE A VAPORE E A GAS

4378-13

NAFTENI IN FRAZIONI SATURE (REFRACTIVITY INTERCEPT)

2159-93

NUMERO ACIDITÀ E BASICITÀ (TITOLAZIONE CON INDICATORE)

6618:1997/cor 1:1999 139/98(04) 974-12

NUMERO ACIDITÀ,VALORE DI NEUTRALIZZAZIONE (TITOLAZIONE CON INDICATORE)

1/94(04)

NUMERO DI ACIDITÀ (TITOLAZIONE POTENZIOMETRICA)

6619 :1988 UNI 20025:1989 UNI EN 12634:2001

177/13 664-11a

NUMERO DI ACIDITÀ SEMI-MICRO (TITOLAZIONE CON INDICATORE)

7537:1997 3339-12

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

215

PARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi Italiani IP ASTM D

NUMERO DI BASICITÀ (TITOLAZIONE POTENZIOMETRICA CON ACIDO CLORIDRICO)

4739-11

NUMERO DI BASICITÀ (TITOLAZIONEPOTENZIOMETRICA CON ACIDO PERCLORICO)

3771:2011 UNI 20002:1989 276/12 2896-11

NUMERO DI NEUTRALIZZAZIONE DI OLI ISOLANTI62021-1:200362021-1:2007

CEI EN 62021-1:2005 CEI EN 62.021-2:2007

NUMERO DI PRECIPITAZIONE PER LUBRIFICANTI 91-02 (2012)

NUMERO DI SAPONIFICAZIONE DI PRODOTTI PETROLIFERI

6293-1:1996 6293-2:1998 UNI ISO 6293-1-2:2001

136S1/98(06) 136S2/99(06)

94-07 (2012)

OSSIDAZIONE DI GRASSI (BOMBA) 142/85(10) 942-02 (2007)

OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI INIBITI 943-04a (2010)e1

OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI LUBRIFICANTI 48/12

OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI LUBRIFICANTI “EP” 2893-04 (2014)e1

PCBs IN OLI MINERALI USATI (GC) -QUANTIFICAZIONE 12766-2:2001 UNI EN 12766-2:2004

PCBs IN OLI MINERALI USATI (GC+ECD) 12766-1:2000 UNI EN 12766-1:2001

PCT E PCBT IN OLI MINERALI USATI (GC+ECD) 12766-3:2004 UNI EN 12766-3:2005

PENETRAZIONE DI GRASSI CON CONO 2137:2007 NOM 38:2002 50/12 217-10

PENETRAZIONE DI GRASSI CON CONO A SCALA 1/4 E 1/2

UNI 20033:1992 1403-10

PENETRAZIONE DI PARAFFINE CON AGO UNI 20004:1989 1321-10

PENETRAZIONE DI PETROLATI CON CONO 2137:2007 179/79 (04) 937-07 (2012)

PENTACLOROBIFENILI E OMOLOGHI MAGGIORM, CLORURATI (in ASKAREL)

60588:1979 CEI 10-6:1997

PERDITA PER EVAPORAZIONE (NOACK) 5800-14

PERDITA PER EVAPORAZIONE DI OLI E GRASSI

972-02 (2008)

PERSISTENZA DELLA FIAMMELLA IN FLUIDI RESISTENTI AL FUOCO

14935:1998 UNI EN ISO 14935:2000

pH DI ANTICONGELANTI E ANTIRUGGINI MOTORI 1287-11

POLARI, AROMATICI E SATURI IN OLI PLASTIFICANTI ED ESTENSORI (METODO CROMATOGRAFICO)

2007-11

POLICLOROBIFENILI IN OLI MINERALI ESAUSTI (GC+ECD)

UNI 12766-1:2001

POLICLOROBIFENILI IN OLI MINERALI ISOLANTI (GC impaccata)

4059-00 (2010)

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

216

PARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi Italiani IP ASTM D

POLICLOROBIFENILI IN OLI MINERALI ISOLANTI (GC capillare)

61619:1997 CEI EN 61619:1998

POLINUCLEARI AROMATICI IN OLI USATI UNI 20030:1992 346/92(04)

POMPABILITÀ OLIO, TEMPERATURA 3829-14

PRODOTTI PETROLIFERI, TABELLE DI CONVERSIONE 1250-08 (2013)

PROPRIETÀ “EP” DI OLI(MACCHINA 4 SFERE )

UNI 20029:1992 239/07 (14) 2783-03 (2009)e1

PROPRIETÀ “EP” DI GRASSI(MACCHINA 4 SFERE )

2596-10e1

PUNTO DI ANILINA 611-12

PUNTO DI CONGELAMENTO DI FLUIDI REFRIGERANTI PER MOTORI

1177-12

PUNTO DI EBOLLIZIONE DI FLUIDI REFRIGERANTI PER MOTORI

1120-11e1

PUNTO DI FUSIONE DI PARAFFINE3841:19776244:1982 UNI ISO 3841:2001 87-09 (2014)

PUNTO DI GOCCIOLAMENTO DI CERE E PETROLATI 6244:1982 UNI 20034:1992 133/79(01) 127-08

PUNTO DI GOCCIOLAMENTO DI GRASSI2176:1995/cor1:2001 132/96(04) 566-02 (2009)

PUNTO DI GOCCIOLAMENTO DI GRASSI CON PIÙ ALTO RANGE DI TEMPERATURA

2265-06 (2014)

PUNTO DI INFIAMMABILITÀ IN VASO APERTO CLEVELAND

2592:2000 36/02 92-12b

PUNTO DI INFIAMMABILITÀ IN VASO CHIUSO (PENSKY MARTENS)

2719:2002 34/03 93-13e1

PUNTO DI INFIAMMABILITÀ TAG (aperto) 1310-01 (2007)

PUNTO DI INFIAMMABILITÀ TAG (chiuso) 56-05 (2010)

PUNTO DI INTORBIDAMENTO(RAFFREDDAMENTO LINEARE)

3015:1992 2500-11

PUNTO DI SCORRIMENTO 3016:1994 UNI 20065:1997 15/95(14) 97-12

PUNTO DI SCORRIMENTO AUTOMATIZZATO 6892-03 (2014)

PUNTO DI SOLIDIFICAZIONE DI PARAFFINEE PETROLATI

2207:1980 UNI 20005:1989 76/70(04) 938-12

RESIDUO CARBONIOSO CONRADSON 6615:1993 189-06 (2014)

RESIDUO CARBONIOSO RAMSBOTTOM 4262:1993 UNI 20042:1992 524-10

RESIDUO CARBONIOSO, METODO MICRO 10370:2014 UNI EN ISO 10370:1998 4530-11

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

217

PARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi Italiani IP ASTM D

RIGIDITÀ DIELETTRICA DI OLI ISOLANTI 60156:1995

RIGIDITÀ DIELETTRICA DI OLI TRASFORMATORE 60296:2012 CEI EN 60296:2013

RILASCIO ARIA DI OLI MINERALI 9120:1997 NOM 121:2002 3427-14

RUGGINE, PROVA DINAMICA PER GRASSI (EMCOR )

UNI 20036:1992

SCHIUMEGGIAMENTO DI ANTICONGELANTI 1881-97 (2009)

SCHIUMEGGIAMENTO DI OLI LUBRIFICANTI6247:1998/cor 1:1999 UNI 20023:1989 146/10 892-13

SEDIMENTI IN TRACCE NEGLI OLI LUBRIFICANTI 2273-08 (2012)

SEPARAZIONE DI OLIO DA GRASSO LUBRIFICANTE 6184-98 (2005)

SEPARAZIONE DI OLIO DA GRASSI DURANTE LO STOCCAGGIO

1742-06 (2013)

SFORZO DI SOGLIA E VISCOSITÀ APPARENTE (A BASSA TEMPERATURA)

4684-14

SOLFONATI NATURALI E SINTETICI (HPLC) 3712-05 (2011)

SPECIFICA DI LIQUIDI SILICONICI PER USI ELETTRICI60836:200560944:1988

CEI EN 60836:2005

SPECIFICA DI OLI MINERALI ISOLANTI 60296:2012 CEI EN 60296:2013

SPECIFICA PER CAPILLARI VISCOSIMETRICI 3105:1994 UNI ISO 3105:2001 71S2/95(04) 446-12

STABILITÀ AL ROTOLAMENTO DI GRASSI UNI 20018:1989 1831-11

STABILITÀ ALL’ OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI MINERALI INIBITI PER TURBINE

UNI 20019:1989 280/99(11)

STABILITÀ ALL’OSSIDAZIONE DI LIQUIDI ISOLANTI NUOVI A BASE IDROCARBURI

61125:1992 am1:2004

CEI EN 61125/97+ A1:2005

STABILITÀ ALL’OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI PER TURBINE A VAPORE (BOMBA)

2272-14a

STABILITÀ IDROLITICA DI OLI IDRAULICI 2619-09 (2014)

STABILITÀ TERMICA ( in ASKAREL) 60588:1979 CEI 10-6:1997

TENDENZA A FORMARE DEPOSITI E CORROSIONE 4310-10

TENSIONE DI SCARICA LIQUIDI ISOLANTI 60156:1995 CEI EN 60156:1998

TENSIONE INTERFACCIALE DI OLI (METODO RING)

6295:1983 971-12

TRAFILAMENTO DI GRASSI NEI CUSCINETTI UNI 20054:1993 1263-94 (2005)e1

CARATTERISTICHE ANTIUSURA DI GRASSI LUBRIFICANTI (MACCHINA TIMKEN)

2509-03 (2008)

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

218

PARAMETRO ANALITICO EN-ISO-IEC Metodi Italiani IP ASTM D

CARATTERISTICHE ANTIUSURA DI GRASSI LUBRIFICANTI (MACCHINA 4 SFERE)

2266-01 (2008)

CARATTERISTICHE ANTIUSURA DI OLI LUBRIFICANTI (MACCHINA 4 SFERE )

4172-94 (2010)

USURA DI OLI IDRAULICI 4998-13

USURA DI PELLICOLE SOLIDE DI LUBRIFICANTE 2981-94 (2014)

USURA E ATTRITO (MACCHINA FALEX) 2714-94 (2014)

PROPRIETÀ EP DI GRASSI (MACCHINA SRV) 5706-11

PROPRIETÀ EP DI OLI LUBRIFICANTI(MACCHINA TIMKEN)

2782-02 (2014)

VISCOSITÀ CINEMATICA3104:1994/cor 1:1997 UNI EN ISO 3104 :2000 71S1/97 445-14e2

VISCOSITÀ /TEMPERATURA, DIAGRAMMA 341-09

VISCOSITÀ AD ALTI GRADIENTI 4683-13

VISCOSITÀ APPARENTE DI GRASSI 1092-12

VISCOSITÀ APPARENTE DI OLI MOTORE(CCS)

5293-14

VISCOSITÀ DI LUBRIFICANTI TRAZIONE (BROOKFIELD)

UNI 20028:1992 2983-09

VISCOSITÀ DI OLI TURBINA DOPO PERMANENZA A BASSA TEMPERATURA

2532-10

VISCOSITÀ/TEMPERATURA DI OLI A BASSA TEMPERATURA, RELAZIONE

5133-13

VISCOSITÀ-GRAVITA’ CALCOLO DELLA COSTANTE (VGC)

2501-14

ZOLFO (BOMBA) 129-13

ZOLFO (FLUORESCENZA RAGGI X) 8754:2003 4294-10

ZOLFO (METODO AD ALTA TEMPERATURA) 1552-08 (2014)e1

ZOLFO (METODO WICKBOLD) 4260:1987

ZOLFO (FLUORESCENZA UV) 5453-12

ZOLFO ATTIVO DI OLI DA TAGLIO 1662-08 (2014)

ZOLFO CORROSIVO DI OLI ISOLANTI 62535:2008 UNI 20052:1992 315/98(04) 1275-06

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

219

TABELLA LUBRIFICANTI - COMMENTO ALLE NUOVE REVISIONI DEI METODI ASTM (Dicembre 2014)

PARAMETRO ANALITICO ASTM D COMMENTO

CARATTERISTICHE ANTIRUGGINE 665-14

Rivista Nota 1: l’indicazione del materiale plastico è più generica e non limitata al PTFE.Cambiata l’unità di misura rpm con r/min.Aggiunta terminologia riguardante la definizione di ruggine al punto 3.Acqua di mare sintetica: sostituito CaCl

2 anidro con

CaCl2∙2H

2O per coerenza con IP 135/06.

Rivisto il punto 13 – Interpretazione dei risultati.Tecnicamente equivalente all’edizione 2012 (si consiglia la lettura).

ELEMENTI DI ADDITIVAZIONE, METALLI DI USURA E CONTAMINANTI IN OLI LUBRIFICANTI USATI E OLI BASE (ICP-AES)

5185-13e1Revisioni editoriali: rivista tabella 4, in “Metalli di usura” sostituito l’Argon con l’ Antimonio.Equivalente all’edizione 2013.

ELEMENTI DI ADDITIVAZIONE IN OLI LUBRIFICANTI (ICP-AES) 4951-14

Aggiunto punto 4.3 e Tabella 1 con la spiegazione del ruolo degli additivi per un miglioramento di performance dei lubrificanti.Equivalente all’edizione 2009.

GASOLIO IN LUBRIFICANTI USATI (GC) 3524-14

Metodo ritirato nel gennaio 2013.Riemessa edizione corrente, approvata e pubblicata nel maggio 2014.Equivalente edizione 2004.

INSOLUBILI IN OLI USATI 893-14Rivisto punto 6.3: caratteristiche del forno (a prova di esplosione e di classe A).Equivalente all’edizione 2012.

OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI LUBRIFICANTI “EP” 2893-04(2014)e1Riapprovata edizione del 2004. Aggiunta Nota editoriale alla sezione 6.1 (aggiornato Warning per l’acido cromico).Equivalente all’edizione 04(2009).

PERDITA PER EVAPORAZIONE (NOACK) 5800-14

Cambiati i valori di precisione per le procedure B e C, che risultano simili tra loro (Nota 6 a piè di pagina).Ampliato il numero di campioni e di laboratori che hanno partecipato alle prove interlaboratorio per i dati di precisione.Non equivalente all’edizione 2010.

POMPABILITÁ OLIO, TEMPERATURA 3829-14

Rivisto il punto 2: documenti di riferimento.Inserita Nota 1 che eguaglia il DCT (Digital Contact Thermometer) al PET (Portable Electronic Thermometer). Aggiunte al punto 6.1.1 le tolleranze per le dimensioni dello strumento.Le caratteristiche degli oli per la calibrazione sono state spostate dal punto 3 al punto 7.Rivisti i punti: Scopo, Calibrazione, Misura e Calcolo.Tecnicamente equivalente all’edizione 2012 (Si consiglia la lettura).

PROPRIETÁ EP DI OLI (MACCHINA 4 SFERE) 2783-03(2009)e1Introdotta correzione editoriale al punto 3.1.9 (introdotto il punto 3.1.9.1 Discussione)Equivalente all’edizione 03(2009).

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

220

PARAMETRO ANALITICO ASTM D COMMENTO

PROPRIETÁ EP DI GRASSI (MACCHINA 4 SFERE) 2596-10e1Introdotta correzione editoriale al punto 3.1.9 (introdotto il punto 3.1.9.1 Discussione)Equivalente all’edizione 2010.

PUNTO DI INFIAMMABILITÀ IN VASO CHIUSO (PENSKY MARTENS)

93-13e1

Revisione editoriale al punto 15: riportare il risultato con riferimento al metodo usato ( ASTM D93 o IP 34, procedura A, B o C).Equivalente all’edizione 2013.

RILASCIO ARIA IN OLI MINERALI 3427-14

Al punto 6.1.5 sostituita la parola host fittings con hose fittings.Al punto 6.5 cronometro: deve avere una precisione di 1 secondo, con un’accuratezza migliore dell’1%.Aggiunta sezione 8 per la preparazione del campione in accordo alla norma D4057.Rinumerati i punti da 9 a 13.Modificata l’espressione del risultato in secondi.Non equivalente all’edizione 2012.

SFORZO DI SOGLIA E VISCOSITÁ APPARENTE ( A BASSA TEMPERATURA)

4684-14

Riviste il punto 6.4.1: caratteristiche del termometro digitale.Rivisto il punto 2: documenti di riferimento.Rivisti i punti: Scopo, Definizioni, Materiali, Calibrazione, Misura e Calcolo.Tecnicamente equivalente all’edizione 2012 (Si consiglia la lettura).

STABILITÁ ALL’OSSIDAZIONE DI OLI PER TURBINE A VAPORE (BOMBA)

2272-14a

2272-14: rivisto il punto 7 Campionamento.Cambiati i dati di precisione del metodo A e B.Introdotte nell’Annesso A1 e A2 le calibrazioni per la Temperatura e per la Pressione.2272-14a: nell’Annesso A1 e A2 la durata delle calibrazioni di Pressione e Temperatura deve essere annuale.Non equivalente alla versione 2011.

VISCOSITÁ CINEMATICA 445-14e2

445-14: aggiunto il punto 6.6 con indicazione del bagno ad ultrasuoni. Aggiornato il punto 11.1 per i campioni che trattengono l’aria. Aggiornato il punto 17 con i dati di precisione per cherosene, diesel e biodiesel.445-14e1: correzioni editoriali al punto 17.1.1 determinabilità.445-14 e2: correzioni editoriali al punto 17Equivalente all’edizione 2012 (si ricorda che sono stati ampliati i dati di precisione per i prodotti cherosene, diesel e biodiesel).

VISCOSITÁ APPARENTE DI OLI MOTORE (CCS) 5293-14

Aggiunti i punti 6.6 e 9.2 (indicazioni del bagno ad ultrasuoni da usare per dissipare eventuali bolle d’aria presenti in campioni viscosi).Equivalente all’edizione 2010e1.

VISCOSITÁ – GRAVITÁ CALCOLO DELLA COSTANTE 2501-14Aggiunto il metodo D7042 al punto 5.1 e 5.2.Equivalente all’edizione 2011.

ZOLFO (METODO AD ALTA TEMPERATURA) 1552-08(2014)e1Cancellata nota a piè di pagina n°3: riferimento ad uno strumento.Equivalente all’edizione 2008.

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

221

A. M. GiuffrèDipartimento AGRARIA

Università degli Studi “Mediterranea” di Reggio Calabria

CORRESPONDENCE: dr. Angelo M. Giuffrè

Dipartimento AGRARIAUniversità degli Studi “Mediterranea”

di Reggio Calabria (Italia)E-mail: [email protected].

Phone +39 (0) 965.324077Fax +39 (0) 965.311092

Variation in triacylglycerols of olive oils produced in Calabria (southern italy)

during olive ripening

Variations in the triacylglycerol (TAG) content of virgin and extra virgin olive oil from cultivars grown in South West Calabria (Southern Italy) were studied every two weeks for three harvest years 2005-2006-2007. Three autochtho-nous cultivars from Calabria: Cassanese, Ottobratica and Sinopolese and seven allochthonous cultivars: Coratina, Itrana, Leccino, Nocellara Messi-nese, Nociara, Pendolino and Picholine were considered. With regard to the TAG evolution, the highest quantity was triolein (OOO) which increased dur-ing ripening; one of the minor components found was trilinolein (LLL) which decreased. A decreasing trend was observed for POO+SOL, the second major detected peak. Triacylglycerols were grouped by considering their Equivalent Carbon Number (ECN). The ANOVA analysis demonstrated that the cultivar influenced the TAG composition at each harvest date and differ-ences were statistically very highly significant (p ≤ 0.001), as well the harvest date influenced the TAG composition of each cultivar and differences were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05), highly significant (p ≤ 0.01) and very highly significant (p ≤ 0.001).Keywords: Calabria, cultivar, maturation, Olea europaea L., olive oil, ripening, triglycerides.

Variazione dei trigliceridi degli oli di oliva prodotti in Calabria (Italia meridionale) durante la maturazione delle olive È stata studiata la variazione nel contenuto in triacilgliceroli (TAG) da oli extra vergini di oliva estratti da olive campionate ogni due settimane per tre annate (2005-2006-2007) da cultivar allevate nel sud ovest della Calabria (Sud Ita-lia). Sono state considerate tre cultivar autoctone: Cassanese, Ottobratica e Sinopolese e sette cultivar alloctone: Coratina, Itrana, Leccino, Nocellara Messinese, Nociara, Pendolino e Picholine. Rispetto all’evoluzione dei triacil-gliceroli, la quantità maggiore era di trioleina (OOO) che aumentava durante la maturazione delle olive. Uno dei componenti presenti in minore quantità era la trilinoleina (LLL) che invece diminuiva. È stato osservato un andamento decrescente per POO+SOL, il secondo maggiore picco individuato.I triacilgliceroli sono stati raggruppati considerando il loro numero di carbonio equivalente (ECN). L’analisi della varianza (ANOVA) ha dimostrato che la cultivar ha influenzato la composizione di triacilgliceroli in ciascuna data di raccolta e le differenze sono molto altamente significative (p ≤ 0.001), come anche la data di raccolta ha influenzato la composizione di triacilgliceroli in ciascuna cultivar e le diffe-renze sono state significative (p ≤ 0.05), molto significative (p ≤ 0.01) e molto altamente significative (p ≤ 0.001).Parole chiave: Calabria, cultivar, maturazione, Olea europaea L., olio d’oliva, trigliceridi.

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

222

1. INTRODUCTION

Acylglycerols are the main constituents of olive oil (more than 98%) and TAGs represent the largest part of acylglycerols. Mono and diacylglycerols gener-ated by hydrolysis of TAGs are present in olive oil as secondary constituents and in low percentages. All glyceride percentages are related to the free acidity of the olive oil. TAGs in fats and in vegetable oils are a chemical combination of glycerol and fatty acids. Fatty acids in olive oil can be saturated or unsaturated and with medium and long chains ranging from 14 to 24 atom carbon numbers. The stereospecific position of fatty acids is important because it determines how triglycerides are digested. Fatty acids released from the sn-1 and sn-3 positions often have different metabolic fates than fatty acids retained in the sn-2 position. These metabolic fates depend on the fatty acid chain-length and stereospe-cific location on the triglyceride [1]. Triacylglycerols (TAG) are the major storage and trans-port forms of energy that provide 9 kcals/g. Under normal conditions, humans consume about 90-120 g of fat per day and more than 95% of it is absorbed [2].The current evidence argues compellingly for includ-ing triglyceride in the evaluation of patient risk for cor-onary artery disease. For the present, measurement of fasting triglyceride and its assessment in conjunc-tion with LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol con-centrations would seem to be the most practical way of evaluating any additional risk posed by hypertrig-lyceridemia [3].The origin, cultivar, extraction technology, state of rip-ening of the fruit, climatic conditions, and rainfall all influence biosynthesis within the fruit and, therefore, the composition and quality of the oil [4].Triacylglycerol (TAG) composition is a critical charac-teristic in the quality of fats and oils because it can affect not only their physiological properties such as melting point and crystallization but also their nutri-tional properties such as susceptibility to lipase-hy-drolysis [5]. The Italian olive germplasm is estimated to include about 800 cultivars, most of them being landraces vegetatively propagated at a farm level since ancient times. The number is probably underestimated be-cause of the scarce information on minor local variet-ies widespread in the different olive growing areas [6]. The Calabrian Region has an ancient tradition with re-spect to olive oil production and many cultivars grown in this territory [7], with a specific morphological and genetic structure [8]. It is important to study the oil composition of all Italian cultivars in order to provide for each oil, useful consumer information on the label, especially for the monocultivar oils.In a previous paper the influence of cultivar and har-vest year on triglyceride composition of olive oil for each of the three harvest years was studied. Find-

ings showed that the cultivar effect had a significant or highly significant influence on TG composition. The effect of harvest year and the combination cultivar × harvest year showed a lower influence [9]. In the same microclimatic, agronomic and oil’s extrac-tive conditions, the cultivar and the harvest date were proved to influence also the sterols [10, 11], fatty al-cohols [12, 13] and waxes [14, 15]. The harvest date was also proved to influence phenolic and fatty acid methly ester composition [16].The aim of this paper is to study the TAG composition of pressed virgin olive oils from autochthonous and allochthonous cultivars grown in South West Calabria (Southern Italy). Particular emphasis is placed on the variation on TAG composition during olive ripening. No previous data exists regarding the TAG evolution of olive oil during harvest time in this geographical area.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

PLANT MATERIAL AND EXTRACTION SYSTEMDrupes from olive trees were sampled in three harvest years 2005, 2006 and 2007 from plantations in the Plain of Gioia Tauro situated in South West Calabria (Southern Italy). In each plantation only one cultivar was grown. All plantations were in the same micro-climatic conditions, at 100 m above sea level, with damp and rainy winters and hot summers. Cassanese (7 samplings), Ottobratica (7 samplings) and Sinopo-lese (7 samplings) are autochthonous cultivars for the Region of Calabria. Coratina (5 samplings), Itrana (5 samplings), Leccino (5 samplings), Nocellara Messi-nese (7 samplings), Nociara (6 samplings), Pendolino (6 samplings) and Picholine (5 samplings) are alloch-thonous for this region. For Nocellara Messinese only one sampling was conducted in the harvest year 2005. No nutrient and water deficiency or pest damage were found on the trees. Drupes were harvested every two weeks from the beginning of October until 20% ripe fruits were no longer found on trees. For each harvest approximately 40 kg of olives per cultivar were picked (more or less 2.5 kg per tree) from fifteen previously selected 25-40 year old plants. At each harvest olives were randomly hand picked and quickly transferred to the laboratory. Before oil extraction, leaves were re-moved and olives were washed in fresh water.Olives were immediately processed in a laboratory mill “Mini 30” (AGRIMEC Valpesana, Calzaiolo, S. Casciano VP, Florence), with a capacity of 40 kg. Ol-ive crushing, the first step, was conducted by means of a hammer-mill. Malaxation of olive paste, the sec-ond step, was conducted at a temperature between 15 and 20°C for 35 minutes. The prepared paste was placed between a pile of circular metallic grids and pressed using a hydraulic press with a mild and con-tinuous increase in pressure up to 200 bar. The liquid phase was submitted to separation by centrifugation and the obtained oil was filtered through filter paper.

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

223

Amber glass flasks (100 mL) were filled as completely as possible with oil to minimize oxidation. The flasks were then stored in dark conditions at 15-20°C, until analysis.

CHEMICALSStandard samples of trimyristin, tripalmitin, tristearin, triolein, 1,2-palmitolein-3olein, 1,2-stearin-3olein, from Larodan Fine Chemicals, Malmö (Sweden), were used as references. Acetonitrile, acetone, diethyl ether, petroleum ether were from Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy. Silica gel 70-230 mesh, was from Merck S.p.A., (Milan, Italy).

Determination of triacylglycerolsThe identification and quantification of TAGs was conducted as described in Annex XVIII of the Eu-ropean Regulation [17]. A comparison of retention indices with those of authentic samples was made. The olive oil was purified through a silica-gel column using petroleum ether/ethyl ether (87/13) as an elu-ent and then filtered. The solvent was eliminated by means a Rotavapor. A 10 µl aliquot of sample (5% of purified olive oil in acetone) was used for the HPLC analysis with an isocratic mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile + acetone (50/50) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. An HP instrument was used equipped with a re-fractive index detector, using a 3 × 200 mm × 3 µm, C18 column (Varian Scientific, Lake City, CA, USA).

STATISTICAL ANALYSISAnalyses were conducted in triplicate. Excel software (2003 version) was used for graph constructions. Percentage relative standard deviations (%RSD) were calculated as follows: standard deviation (SD)/mean × 100. Data were also determined by analysis of vari-ance (ANOVA) using SPSS version 15.0 for Windows (IL, USA). The Tukey test was used to determine any significant difference among all of the treatments at p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

For autochthonous cultivars and Nocellara Messinese it was possible to collect drupes from trees from the 2nd October until the end of December. By contrast for all the other allochthonous cultivars it was possible to find olives on trees only until the 1st or the 16th of December. It is noteworthy that Nocellara Messinese originates from the North of Sicily (Southern Italy) which has a similar latitude to the South of Calabria.In the TAG chromatograms 19 peaks were detected, 14 of them representing only one triacylglycerol and 5 of them representing two triacylglycerols: 1.LLL, 2.OLLn+PoPoL, 3.PLLn, 4.OLL, 5.OOLn+PoOL, 6.PLL, 7.POLn, 8.PoPoP, 9.OOL, 10.POL+PoPO, 11.PPL, 12.SOLn, 13.OOO, 14.POO+SOL, 15.PPO+PSL, 16.GaOO, 17.SOO, 18.PSO, 19.SSO, being: P = palmitic; Po = palmitoleic; S = stearic; O =

oleic; L = linoleic; Ln = linolenic; Ga = gadoleic (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – HPLC Triacylglycerol chromatogram of a Calabrian olive oil. 1.LLL; 2.OLLn+PoPoL; 3.PLLn; 4.OLL; 5.OOLn+PoOL; 6.PLL; 7.POLn; 8.PoPoP; 9.OOL; 10.POL+PoPO; 11.PPL; 12.SOLn; 13.OOO; 14.POO+SOL; 15.PPO+PSL; 16.GaOO; 17.SOO; 18.PSO; 19.SSO.

Minutes

mV

For all the detected triglycerides the Equivalent Car-bon Number (ECN) was calculated, defined by the re-lation ECN = CN – 2n, where CN is the carbon num-ber and n is the number of double bonds (CONLEG, 2003), and triacylglycerols were grouped as follow: ECN42 = LLL + OLLn + PoPoL + PLLn. ECN44 = OLL + OOLn + PoOL + PLL + POLn + PoPoP. ECN46 = OOL + POL + PoPO + PPL + SOLn. ECN48 = OOO + POO + SOL + PPO + PSL. ECN50 = GaOO + SOO + PSO. ECN52 = SSO.Results were expressed as a mean of three years of harvest: 2005, 2006 and 2007.

TRIACYLGLYCEROL VARIATIONLLL was one of the TAGs contained in lower amounts in all cultivars and showed a decreasing trend dur-ing ripening, in particular Itrana had the lowest LLL content ranging between 0.05% to 0.02% of the total TAGs. The highest LLL content (0,11%) was found in Ottobratica at the first harvest stage and in Nocellara Messinese in October and November (Table I). Similar findings were described from oil from the Koroneiki cv grown in Crete [18], from oil from the Galega Vulgar cultivar in Portugal [19] and in the Spanish Cornicabra cultivar [20]. A higher LLL percentage was found in Iranian olive oils [21] and in Tunisian cultivars [22]. RSDs of trilinolein in the studied cultivars ranged be-tween 11.45% in Nocellara Messinese and 36.03% in Cassanese, indicating a large spread of results during olive ripening (Table I). The OLLn+PoPoL peak appeared second in the TAG profile. Each cultivar showed a similar content be-tween October and December, except the Cassanese, which showed a diminution of about 50% (from 0.65% to 0.29%) during ripening. RSDs of OLLn+PoPoL in the cultivars grown in Calabria ranged from 9.91% in

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

224

Leccino to 27.85% in Pendolino, also in this case with a large spread of results (Table II).PLLn was constant during olive maturation and re-mained below 0.18%. Only in the first ripening stage of Cassanese a 0.25% content was found (Table III). In all the studied cultivars, at the end of ripening a PLLn content ≤ 0.11% was found, similar to contents in the Galega Vulgar cultivar (Spain) [19] and in Ira-nian olive oils [21]. Nociara showed the lowest %RSD (8.41) and Ottobratica the highest %RSD (48.84), (Table III). OLL was lowest in Itrana among the allochthonous cultivars, remaining below 0.50%, and in Sinopolese among the autochthonous cultivars, accounting from a maximum of 1.22% and a minimum of 0.89%. The majority of cultivars showed a %RDS within 20%, ex-cept for Ottobratica and Nocellara Messinese, with a 23.24% and 25.65% value, respectively (Table IV).The OOLn+PoOL peak appeared fifth in the TAG pro-file. Nocellara Messinese had the highest OOLn+PoOL content on all the seven sampling dates, accounting for between 2.45% and 3.11% of the total TAGs. In all other cultivars the OOLn+PoOL content was always below 2%; in Ottobratica the OOLn+PoOL account-ed for less than 1% throughout the ripening period. This peak showed one of the lowest variations during ripening and the %RSD was less than 12.50 for all cultivars (Table V). The PLL value decreased throughout ripening for Cassanese, Sinopolese and Pendolino. The PLL con-tent was 1.14% and 0.95% respectively on the first and on the second harvest dates of Cassanese and remained constantly below 0.85% of total TAGs for all other cultivars in all the harvest stages. The autochtho-nous cultivars presented three of the highest %RSD, ranging from 25.71 to 37.84. In particular Cassanese showed the highest SD (± 0.27) and %RSD (37.84), (Table VI). Some Authors studied Spanish olive oils of the Extremadura Region from seven cultivars extract-ed at different stages of ripening and always found a PLL content lower than 0.80% [23]. Compared to the olive oil of South West Calabria, an higher PLL amount was found in Picholine Marocaine olive oil from three different sites (1,75%, 2.02% and 2,15% respectively), although other Moroccan autochtho-nous cultivars showed a similar content [24].The POLn content decreased from the first to the last stage of this study for Cassanese (1.34% - 0.62%) and Pendolino (1.29% - 0.89%) and remained con-stantly below 0.93% for all other cultivars throughout ripening. Leccino showed the lowest %RSD (5.25). The highest SD and %RSD were found in Cassanese (±0.24 and 27.09, respectively) (Table VII). PoPoP was another of the TAGs contained in a lower amount in all cultivars and showed a constant con-tent for Sinopolese, Coratina and Nociara and a vary-ing content during their growth for the seven remain-ing cultivars. The highest PoPoP content (0.15%) was found in Cassanese in the first harvest date. Worthy

of note are the RSDs for Sinopolese, Leccino and Nociara (15.59, 39.03 and 69.92 respectively) which presented a very similar standard deviation (±0.01) and a different mean; this is explained by the influ-ence of the mean on this parameter (Table VIII).OOL showed a constant increase in Ottobratica (11.57% - 15.94%), in Nociara (10.90% - 16.07%), in Picholine (13.66% - 15.92%), whereas in Nocellara Messinese the content was constant for the first four sampling dates (12-13%) and increased rapidly in De-cember (12.26% - 20.82%). The %RSD was 25.43 in Nocellara Messinese and less than 15.50 in all other cultivars (Table IX).POL+PoPO was the tenth detected peak in the HPLC chromatogram. POL+PoPO declined constantly in Cassanese from the first to the seventh sampling of growth from 9.75% to 5.34% with a drop of 45.23%. Also Coratina and Pendolino had a fall in POL+PoPO (4.98% - 3.98%) and (6.43% - 4.74%) respectively. In general, the concentation of POL+PoPO remained below 8% in all cultivars for most of their growth ex-cept for Nocellara Messinese in which the sum of these two TAGs was always above 10% of the to-tal TAGs. Cassanese showed the highest SD (±1.58) and the highest %RSD (22.25), (Table X).PPL was always above 15% for Ottobratica, Sinoplese and Nocellara Messinese and below 15% for all oth-er cultivars during ripening. All cultivars presented a %RSD higher than 15.50; the highest value was in Picholine (45.43) (Table XI).SOLn decreased for Cassanese from 1.26% to 0.49% and increased for Nociara from 0.60% to 0.95%. No-cellara Messinese was notable for a SOLn content higher than 1.30% in all the seven ripening stages. Similar to other cases, Cassanese presented the highest SD (± 0.26) and the highest %RSD (33.27), (Table XII).OOO was the highest TAG found in all cultivars and constituted 30-50% of the total TAGs, also in this case Cassanese presented the highest SD (5.43) and the highest %RSD (13.34). A %RSD ranging from 6.89 to 8.46 was calculated for Pendolino and Nocellara Messinese. The seven remaining cultivars presented a %RSD lower than 5.00, (Table XIII). OOO increased 1.5 times from 2nd October to 31st Decem-ber (31.96%-47.39%), in Cassanese oil. All other cul-tivars had a slight or very slight increase except for Nociara which showed a slight fall from the beginning of October to the end of December. The highest OOO percentage, 51% ca. was found in Coratina on the last two sampling dates. Mateos et al. found in Pic-ual and Hoijiblanca cultivars a OOO content ranging between 50-51%; in Chemlali a 29.84% content and in Picholine 42.24% [25]. This is similar to Picholine of South West Calabria: 40.83%-42.60% on the last two harvest dates. Some researchers measured, in eleven Sardinian and in one Corsican olive oil, a OOO content ranging between 21.21% and 33.22% of the total TAGs, always lower than the minimum found in

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

225

the Calabrian olive oils [26]. A partial microclimatic effect was found by comparing the percentage of OOO in olive oils from different areas of the Extrema-dura Region: Sierra Norte del Cáceres (48.79±3.63), Serena-Siberia (36.15±3.65) and Tierra de Barros (34.81±4.90), [27].POO+SOL was the second highest detected peak for which a constant decline in all cultivars was found, most evident for Ottobratica and least evident in No-cellara Messinese which had the lowest POO+SOL content among all cultivars grown in South West Ca-labria. The POO+SOL was below 30% of the total TAGs in all the studied cultivars at all samplings. All cultivars showed a %RSD lower than 9.50. Leccino showed the lowest SD (±0.50) and the lowest %RSD (1.95), (Table XIV).PPO+PSL was the fifteenth detected peak. All culti-vars exhibited similar profiles of degradation, record-ing a decrease which ranged from 53.77% for Cassa-nese to 10.45% for Nocellara Messinese (Table XV). In all the studied cultivars the maximum PPO+PSL percentage was found in the first stage of harvesting. As it was noted for other compounds, Cassanese presented the highest SD (± 0.78) and the highest %RSD (26.81).GaOO was higher in Coratina which exhibited an in-creasing trend in the later stage of ripening reaching a maximum of 1.2% of total TAGs. This was similar to Cassanese and Ottobratica with a final content of 0.83% and 0.62% respectively. All other cultivars showed a GaOO content lower than 0.7% throughout ripening. Cassanese presented again both the high-est SD (± 0.17) and the highest %RSD (28.09), (Table XVI).SOO was higher in Sinopolese in all the harvesting stages with a 5.80% maximum content at the end of December (Table XVII). A rise in SOO occurred in Cassanese from 2.70% at first sampling to 3.95% at final sampling. All others cultivars showed a relatively constant SOO profile always remaining below 5% of the total TAGs. These results are similar to those of Ollivier et al. [28] who found a SOO content ranging between 2.43% and 4.86% in French olive oils with a registered designation of origin, in six different geo-graphical areas. Ouni et al. [29] in Tunisian olive oils from seven different locations found a similar SOO percentage ranging between 2.50% and 5.50% of the total TAGs. SD and %RSD were higher in Cas-sanese (±0.47 and 13.60 respectively).PSO showed a varying profile in all the cultivars during olive ripening with a content always remaining below 1.30% of total TAGs. The highest %RSD was found in Cassanese (17.73), whereas the lowest was found in Sinopolese (5.75) (Table XVIII).SSO was the last detected TAG and showed a ten-dency to increase in autochthonous cultivars and a stationary trend for the allochthonous, always remain-ing below 1.1% of the total TAGs (Table XIX). The percentage of ECN42 showed little change during

ripening for almost all cultivars, only in Cassanese a decrease was found from 1% to 0.4% during the two months of sampling. Cassanese presented the high-est SD (±0.20) and the highest %RSD (28.09), (Table XX). By and large all the Calabrian cultivars accounted for less than 1% of the total TAGs, similar to the find-ings of Osorio-Bueno et al. [23] for Spanish olive oils from the Extremadura Region. The difference between the theoretical ECN42 and the experimental results achieved by LC analysis (LC ECN42) was found to be a parameter for a rapid and easy analytical approach to detect the presence of 10% hazelnut oil in virgin olive oil [30].The ECN44 percentage was almost constant during harvest time for the allochthonous cultivars: Nocel-lara Messinese having the highest content (8-10%), a slight increase was measured in Nociara. Regard-ing autochthonous cultivars, a decreasing trend was found in Cassanese in contrast with an increasing trend in Ottobratica. In all cultivars the %RSD was less than 18.00; Ottobratica and Cassanese, two au-tochthonous cultivars presented the two highest val-ues (17.30 and 16.47 respectively), (Table XXI). The trend of ECN46 were similar to those of ECN44 with an almost constant concentration for nearly all the allochthonous cultivars with Nocellara Messinese having the highest amount (31-35%), double that of Itrana (14-15%). Nociara, however, showed an increasing trend. For autochthonous cultivars Otto-bratica showed an increase from 19.50% to 24.32%, Cassanese a decrease from 27.56% to 21.46%. No-ciara presented the highest %RSD (15.03), and all other cultivars presented a %RSD less than 10.00 (Table XXII).The ECN48 rates are, again, similar. However, Nocel-lara Messinese is notable for a percentage which re-mained lower than 60% of total TAGs. The %RSD was always less than 5.50 in all cultivars (Table XXIII).The ECN50 percentage was calculated. Also in this case, in the autochthonous group, the oils of Cas-sanese and Ottobratica had a divergent trend. In the allochthonous group, Nocellara Messinese showed a 30% diminution from 2nd October to 31st December and Itrana a 20% increase in the same period. The highest %RSD were found in Nocellara Messinese (12.34) and in Cassanese (11.56), the remaining culti-vars presented less than 9.00 as %RSD, (Table XXIV). In the present study, ECN52 was represented only by one TAG, i.e. SSO, which has already been described (Table XIX).

ANOVA RESULTS

Data are evaluated row by row.Differences are statistically considered for each har-vest date during olive ripening and are: significant (p ≤ 0.05), highly significant (p ≤ 0.01), very highly signifi-cant (p ≤ 0.001). LLL showed significant, high significant or very high

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

226

significant differences in the studied cultivars during ripening and the highest significant values were found in the first three samplings (Table I).OLL content was very highly influenced by the har-vest date in all cultivars. Cassanese, Ottobratica, No-cellara Messinese and Picholine presented different values on each harvest date (Table IV).POLn was always very highly different, in particular, in Cassanese a very high lowering during ripening (p ≤ 0.001) was found (Table VII). PoPoP showed no significant differences in Sinopo-lese on all the harvest dates and it was very highly dif-ferent during ripening in all other cultivars (Table VIII).The harvest date very highly influenced the OOL con-tent of each cultivar and in Nociara caused a very highly significant increase in OOL during olive matu-ration (Table IX).POL+PoPO was very highly different for all cultivars on almost all harvest dates, except for Sinopolese on 1st and 31st December (4.11%) and for Pendolino on 16th November and on 1st December (5.32 - 5.33%), (Table X).SOLn was very highly influenced by the harvest date in all cultivars (p ≤ 0.001). In Cassanese, SOLn per-centage constantly lowered during olive maturation (Table XII). The harvest date very highly affected OOO in all cul-tivars during olive ripening, except in Ottobratica in which the same percentage was found on 2nd Octo-ber and on 1st December (39.32%), (Table XIII).POO+SOL percentage was very highly different in all cultivars during ripening. The autochthonous cultivars and Itrana and Nociara showed a constant increase from early October to the end of December (Table XIV).PPO+PSL was influenced by the harvest date in all cultivars. Cassanese, Ottobratica, Coratina, Itrana, Pendolino, Leccino and Picholine showed very high differences on each harvest date (Table XV).A very high significant effect of the harvest date was found in all cultivars with respect to GaOO and SOO content. In the former, Sinopolese, Coratina and No-cellara Messinese had different values on each har-vest date (Table XVI); the same situation was found in the latter for Cassanese, Ottobratica, Nociara, Pen-dolino and Picholine (Table XVII).ECN42 was very highly different in all the cultivars dur-ing ripening. Itrana showed significant differences on all the harvest dates (Table XX).ECN44 content was very highly influenced by the harvest date in all cultivars. Cassanese, Ottobratica, Coratina, Nocellara Messinese and Nociara always showed a different value on each harvest date (Table XXI).The effect of the harvest date and maturity on ECN46

is presented in Table XXII; findings show very high significant differences for all cultivars during ripening. In particular, ECN46 in Pendolino constantly increased with harvest time and maturity.

ECN48 was very highly different in all the cultivars dur-ing ripening. Cassanese and Nociara had an inverse trend: in the former cultivar the ECN48 percentage constantly decreased whereas in the latter it con-stantly and significantly increased during ripening (Table XXIII).ECN50 was very highly different on all the harvest dates for all the cultivars, this is most evident in Cassanese, Leccino and Picholine (Table XXIV).

Data are evaluated column by column.Differences are statistically considered for each culti-var during olive ripening and are: significant (p ≤ 0.05), highly significant (p ≤ 0.01), very highly significant (p ≤ 0.001). LLL content was very highly influenced by the cultivar on all the harvest dates. Itrana had the lowest content (p ≤ 0.05) during ripening (Table I).The cultivar affected very highly the OLLn+PoPoL and the PLLn content on each harvest date. In both cases Itrana showed the lowest or the second lowest percentage (Tables II and III). OLL and POL+PoPO content were very highly affected by the cultivar on each harvest date showing percent-ages significantly different. In both cases the highest percentage on each harvest date was found in Nocel-lara Messinese and in both cases Itrana showed the lowest or the second lowest content (Tables IV, X).The cultivar very highly differentiated OOLn+PoOL, PLL and POLn content (p ≤ 0.001) on all harvest dates (Tables V, VI, VII).OOO was very highly influenced by the cultivar on all the harvest dates with the exception of 16th No-vember when no significant difference was found in Sinopolese and Pendolino, as well on 16th December when Ottobratica and Nociara had the same percent-age. Coratina showed the highest content on the first five samplings (Table XIII). The cultivar very highly influenced the PPO+PSL con-tent on all harvest dates, this is mainly evident on 16th November and on 1st December (Table XV).Also SSO, the only TAG grouped as ECN52 was very highly influenced by the cultivar. Sinopolese showed the highest or the second highest content on each harvest date (Table XIX). ECN42 was very highly affected by the cultivar. In this group Picholine had the third highest content for the first five samplings (Table XX).The cultivar effect very highly influenced the ECN44 on all the harvest dates. The highest effect was found on 17th October and in December (Table XXI). ECN46 was very highly affected by the cultivar. On all the harvest dates the cultivar effect caused different values. Itrana showed the lowest ECN46 content on the first five harvest dates, Sinopolese was always the second lowest and Coratina was always the third lowest (Table XXII). ECN48 was very highly influenced by the cultivar on all the harvest dates. Itrana showed the highest ECN48

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

227

content on the first five harvest dates whereas No-cellara Messinese had the lowest content from 2nd October to 31st December (Table XXIII). The cultivar very highly influenced the ECN50 content on all the harvest dates and in many cases Otto-bratica and Sinopolese, two autochthonous cultivars, had the highest content. In December the differences found in ECN50 were the most evident (Table XXIV).

4. CONCLUSIONS

All the oils studied in this paper were produced from olives grown in the same geographical area and with the same microclimatic conditions. The same agro-nomic conditions and the same extraction procedure were also applied to all the cultivars, consequently, all variations in TAG content are dependent on the cul-tivar and the ripening stage factors. LLL, PLLn, PLL, POLn, POL+PoPo, SOLn, OOO, PPO+PSL, GaOO, SOO and ECN42 showed both the highest SD and %RSD in the Cassanese. The ANOVA analysis dem-onstrated that the cultivar influenced the TAG com-position at each harvest date and differences were statistically very highly significant (p ≤ 0.001), as well the harvest date influenced the TAG composition of each cultivar and differences were statistically sig-nificant (p ≤ 0.05), highly significant (p ≤ 0.01) and very highly significant (p ≤ 0.001) in the olive oil from olives produced in South West Calabria (Italy). The findings of this study contribute to the knowledge of the composition of South West Calabrian olive oil dur-ing ripening and can consequently inform one of the choice for the most suitable moment for harvesting.

REFERENCES

[1] J.E. Hunter, Studies on effects of dietary fatty acids as related to their position on triglycerides. Lipids 36, 635-648 (2001).

[2] X.Pan, M.M. Hussain, Gut triglyceride produc-tion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 727-735 (2012).

[3] A.M. Gotto, Triglyceride as a risk for coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 82, 22Q-25Q (1998).

[4] D. Firestone – Olive oil - Bailey’s Industrial Oil and Fat Products, Sixth Edition, Six Volume Set. Edited by Fereidoon Shahidi. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

[5] Y. Endo, A. Ohta, H. Kido, M. Kuriyama, Y. Saka-guchi, S. Takebayashi, H. Hirai, C. Murakami, S. Wada, Determination of triacylglycerol compo-sition in vegetable oils using high-performance liquid chromatography: a collaborative study. J. Oleo Sci. 60, 451-456 (2011).

[6] I. Muzzalupo, Olive Germplasm – Italian Cata-logue of Olive Varieties.

http://www.intechopen.com/books/olive-germ-

plasm-italian-catalogue-of-olive-varieties. Edited by Innocenzo Muzzalupo, ISBN 978-

953-51-0884-9. Published by InTech, Janeza Trdine 9, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia.

[7] A.M. Giuffré, L’olio di oliva calabrese: aspetti produttivi e tecnologici. Industrie Alimentari 42, 20-25 (2003).

[8] F. P. Marra, T. Caruso, F. Costa, C. Di Vaio, R. Mafrica, A. Marchese, Genetic relationships, structure and parentage simulation among the olive tree (Olea europaea L. subsp. europaea) cultivated in Southern Italy revealed by SSR markers. Tree Genet. Genomes 9, 961-973 (2013).

[9] A.M. Giuffrè, Influence of cultivar and harvest year on triglyceride composition of olive oils pro-duced in Calabria (Southern Italy). Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 115, 928-934 (2013).

[10] A.M. Giuffré, L. Louadj, Influence of crop season and cultivar on sterol composition of monovari-etal olive oils in Reggio Calabria (Italy). Czech J. Food Sci. 31, 256-263 (2013).

[11] A.M. Giuffré, L. Louadj, M. Poiana, A. Maca-rio, Composition en stérols des huiles extraites d’olives de cultivars de la province de Reggio Calabria (Sud d’Italie). Riv. Ital. Sostanze Grasse 89, 177-183 (2012).

[12] A.M. Giuffré, The effects of cultivar and harvest year on the fatty alcohol composition of olive oils from Southwest Calabria (Italy). Grasas Aceites 65, e011 (2014).

[13] A.M. Giuffré, Evolution of fatty alcohols in olive oils produced in Calabria (Southern Italy) during fruit ripening. J. Oleo Sci. 63, 486-496 (2014).

[14] A.M. Giuffré, Influence of harvest year and culti-var on wax composition of olive oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 115, 549-555 (2013).

[15] A.M. Giuffré, Wax ester variation in olive oils pro-duced in Calabria (Southern Italy) during olive ripening. J. Am Oil Chem Soc. 91, 1355-1366 (2014).

[16] A.M. Giuffré, A. Piscopo, V. Sicari, M. Poiana, The effects of harvesting on phenolic com-pounds and fatty acids content in virgin olive oil (cv Roggianella). Riv. Ital. Sostanze Grasse 87, 14-23 (2010).

[17] Consolidated text, CONSLEG: 1991R2568 - 01/11/2003, on the characteristics of olive oil and olive-residue oil and on the relevant me-thods of analysis, Annex XVIII.

[18] E. Stefanoudaki, F. Kotsifaki, A. Koutsaftakis, The potential of HPLC triglyceride profiles for the classification of Cretan olive oils. Food Chem. 60, 425-432 (1997).

[19] L. Vaz-Freire, J.M.J. Gouveia, A.M. Costa Frei-tas, Analytical characteristics of olive oils pro-duced by two different extraction techniques, in the Portuguese olive variety “Galega Vulgar”. Grasas Aceites 59, 260-266 (2008).

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

228

[20] F. Aranda, S. Gómez-Alonso, R.M. Rivera Del Álamo, M.D. Salvador, G. Fregapane, Triglycer-ide, total and 2-position fatty acid composition of Cornicabra virgin olive oil: Comparison with other Spanish cultivars. Food Chem. 86, 485-492 (2004).

[21] Z. Piravi-Vanak, M. Ghavami, H. Ezzatpanah, J. Arab, H. Safafar, J.B. Ghashemi, Evaluation of Iranian olive oil by fatty acid and triacylglycerol profiles. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 86, 827-833 (2009).

[22] I. Oueslati, H. Manai, F.M. Haddada, D. Daoud, J. Sánchez, E. Osorio, M. Zarrouk, Sterol, triter-penic dialcohol, and triacylglycerol compounds of extra virgin olive oils from some Tunisian va-rieties grown in the Region of Tataouine. Food Sci. Tech. Int. 15, 5-13 (2007).

[23] E. Osorio Bueno, J.J. Sánchez Casas, M. Már-tinez Cano, A.M. Montaño García, Estudio del contenido en triglicéridos de aceites monovarie-tales elaborados a partir de aceitunas produci-das en la region extremeña. Grasas Aceites 54, 1-6 (2003).

[24] N. Boukachabine, H. Ajana, A. El Antari, A study of fatty acids and triglycerides oil composition and quality parameters of five autochthon olive varieties in Morocco. Lebanese Science Journal 12, 45-65 (2011).

[25] R. Mateos, M. Trujllo, M.C. Peä Rez-Camino, W. Moreda, A. Cert, Relationships between oxi-dative stability, triacylglycerol composition, and

antioxidant content in olive oil matrices. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 5766-5771 (2005).

[26] L. Cerretani, A. Bendini, A. Del Caro, A. Piga, V. Vacca, M.F. Caboni, T. Gallina Toschi, Prelimi-nary characterisation of virgin olive oils obtained from different cultivars in Sardinia. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 222, 354-361 (2006).

[27] J. Sánchez Casas, C. De Miguel Gordillo, E. Osorio Bueno, J. Marín Expósito, M. Fuentes Mendoza, T. Ardila Hierro, L. Gallardo Gonzáles, M. Martínez Cano, Characteristics of virgin olive oils from the olive zone of Extremadura (Spain), and an approximation to their varietal origin. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 86, 933-940 (2009).

[28] D. Ollivier, C. Pinatel, N. Dupuy, M. Guérère, J. Artaud, Caractérisations sensorielles et chimi-ques d’huiles d’olive vierges de six AOC fran-çaises. OCL-OL Corps Gras Li. 14, 116-129 (2007).

[29] Y. Ouni, G. Flamini, N. Ben Youssef, M. Guerfel, M. Zarrouk, Sterolic composition and triacylg-lycerols of Oueslati virgin olive oil: comparison among different geographic areas. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 46, 1747-1754 (2011).

[30] S. Vichi, L. Pizzale, E. Toffano, R. Bortolomeazzi, L. Conte, Detection of hazelnut oil in virgin olive oil by assessment of free sterols and triacylglyc-erols. J. AOAC Int. 84, 1534-1541 (2001).

Received, February 18, 2013Accepted, October 29, 2013

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

229

Tabl

e I -

Varia

tion i

n LL

L co

ntent

durin

g oli

ve ri

penin

g for

the

differ

ent c

ultiva

rs. T

he va

lues r

epre

sent

the m

eans

of n

ine re

plica

tes, t

hree

for e

ach

harve

st ye

ar (2

005-

2006

-200

7)

SD.

The

total

me

an an

d the

%RS

D we

re al

so ca

lculat

ed. M

eans

in th

e sam

e ro

w wi

th dif

feren

t lowe

rcase

lette

rs dif

fer si

gnific

antly

. Mea

ns in

the s

ame c

olumn

with

diffe

rent

uppe

rcase

lette

rs dif

fer si

gnific

antly

. In

both

rows

and c

olumn

s: * *

* (p

≤ 0.

001)

, * *

(p ≤

0.01

), *

(p ≤

0.05

), n.s

. (no

t sign

ifican

t).

LLL

2nd O

ct 17

th O

ct 1st

Nov

16

th N

ov

1st D

ec

16th

Dec

31

st D

ec

SD

Mean

%

RSD

Sign

. Ca

ssan

ese

0.08a

bB

0.09a

ABC

0.06b

BC

0.05c

DE

0.04c

BC

0.04c

C 0.0

4cB

0.02

0.06

36.03

* *

* Ot

tobra

tica

0.11a

A 0.0

7bCD

0.0

8bAB

0.0

9abA

B 0.0

8bA

0.07b

B 0.0

8bA

0.01

0.08

16.66

* *

Si

nopo

lese

0.08a

B 0.0

7aCD

0.0

6abB

C 0.0

6abC

DE

0.06a

bAB

0.06a

bBC

0.04b

B 0.0

1 0.0

6 19

.78

* *

Cora

tina

0.08a

B 0.0

8aBC

0.0

6abB

C 0.0

4bEF

0.0

5aBC

--

-- 0.0

2 0.0

6 28

.85

* * *

Itran

a 0.0

4abC

0.0

5aD

0.05a

C 0.0

2bF

0.03a

bC

-- --

0.01

0.04

34.31

* *

* Le

ccino

0.0

8abB

0.0

9aAB

C 0.0

9aA

0.08a

bBC

0.06b

AB

-- --

0.01

0.08

15.31

* *

* No

cella

ra M

essin

ese

0.10a

bAB

0.11a

A 0.0

9abA

0.1

1aA

0.08b

A 0.1

0abA

0.0

9abA

0.0

1 0.1

0 11

.45

* No

ciara

0.0

9aAB

0.0

8abB

C 0.0

8abA

B 0.0

7abc

BCD

0.06b

cAB

0.05c

BC

-- 0.0

1 0.0

7 20

.54

* * *

Pend

olino

0.1

1aA

0.10a

AB

0.09a

A 0.0

6bCD

E 0.0

6bAB

0.0

6bBC

--

0.02

0.08

28.50

* *

* Pi

choli

ne

0.09a

AB

0.08a

bBC

0.08a

bAB

0.06b

cCDE

0.0

5cBC

--

-- 0.0

2 0.0

7 22

.82

* Si

gn.

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

-- --

-- --

Tabl

e II -

Var

iation

in O

OLn+

PoPo

L con

tent d

uring

olive

ripen

ing fo

r the

diffe

rent

cultiv

ars.

The v

alues

repr

esen

t the m

eans

of ni

ne re

plica

tes, t

hree

for e

ach h

arve

st ye

ar (2

005-

2006

-200

7)

SD.

Th

e tot

al me

an a

nd th

e %

RSD

were

also

calcu

lated

. Mea

ns in

the

same

row

with

differ

ent l

ower

case

lette

rs dif

fer si

gnific

antly

. Mea

ns in

the

same

colum

n wi

th dif

feren

t upp

erca

se le

tters

differ

sig

nifica

ntly.

In bo

th ro

ws an

d colu

mns:

* * *

(p ≤

0.00

1), *

* (p

≤ 0.

01),

* (p

≤ 0.

05),

n.s. (

not s

ignific

ant).

OLLn

+PoP

oL

2nd O

ct 17

th O

ct 1st

Nov

16

th N

ov

1st D

ec

16th

Dec

31

st D

ec

SD

Mean

%

RSD

Sign

. Ca

ssan

ese

0.65a

A 0.5

9bA

0.51c

A 0.5

0cdB

0.4

8dA

0.34e

B 0.2

9fB

0.13

0.48

26.60

* *

* Ot

tobra

tica

0.17c

EF

0.15c

G 0.2

1bEF

0.2

1bF

0.23b

CD

0.29a

C 0.2

8aB

0.05

0.22

23.83

* *

* Si

nopo

lese

0.19b

cE

0.16d

FG

0.20b

cF

0.21b

F 0.2

5aC

0.18c

dD

0.21b

C 0.0

3 0.2

0 13

.56

* * *

Cora

tina

0.19b

E 0.2

3aE

0.19b

F 0.1

8bG

0.18b

F --

-- 0.0

2 0.1

9 10

.61

* * *

Itran

a 0.1

6aF

0.18a

F 0.1

3bG

0.16a

G 0.1

1bG

-- --

0.03

0.15

19.08

* *

* Le

ccino

0.2

3bD

0.22b

cE

0.26a

D 0.2

4abE

0.2

0cEF

--

-- 0.0

2 0.2

3 9.9

1 * *

* No

cella

ra M

essin

ese

0.39d

B 0.4

2cC

0.46b

B 0.5

1aAB

0.4

9aA

0.40c

dA

0.36e

A 0.0

6 0.4

3 12

.77

* * *

Nocia

ra

0.29c

C 0.2

9cD

0.35b

C 0.3

5bC

0.22d

DE

0.39a

A --

0.06

0.32

18.97

* *

* Pe

ndoli

no

0.40a

B 0.4

1aC

0.23c

DE

0.29b

D 0.2

2cDE

0.2

7bC

-- 0.0

8 0.3

0 27

.85

* * *

Pich

oline

0.4

0dB

0.46b

B 0.4

6bB

0.53a

A 0.4

3cB

-- --

0.05

0.45

10.57

* *

* Si

gn.

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

-- --

-- --

La rivista itaLiana deLLe sostanze grasse - voL. XCi - ottoBre/diCeMBre 2014

230

Tabl

e III

- Var

iation

in P

LLn

conte

nt du

ring

olive

ripe

ning

for th

e dif

feren

t cult

ivars.

The

value

s rep

rese

nt the

mea

ns o

f nine

repli

cates

, thr

ee fo

r eac

h ha

rvest

year

(200

5-20

06-2

007)

S

D. T

he

total

mean

and

the

%RS

D we

re a

lso c

alcula

ted. M

eans

in th

e sa

me ro

w wi

th dif

feren

t low

erca

se le

tters

differ

sign

ifican

tly. M

eans

in th

e sa

me c

olumn

with

diffe

rent

uppe

rcase

lette

rs dif

fer

signif

icantl

y. In

both

rows

and c

olumn

s: * *

* (p

≤ 0.

001)

, * *

(p ≤

0.01

), *

(p ≤

0.05

), n.s

. (no

t sign

ifican

t).

PLLn

2nd

Oct

17th

Oct

1st N

ov

16th

Nov

1st

Dec

16

th D

ec

31st

Dec

SD

Me

an

%RS

D Si

gn.

Cass

anes

e 0.2

5aA

0.19b

A 0.1

4cA

0.17b

cA

0.18b

A 0.1

4cA

0.07d

B 0.0

6 0.1

6 33

.95

* * *

Ottob

ratic

a 0.0

9cCD

0.0

6deE

0.0

8cdD

E 0.0

5eDE

0.1

9aA

0.15b

A 0.1

0cA

0.05

0.10

48.84

* *

* Si

nopo

lese

0.08a

bD

0.07b

cDE

0.05c

F 0.0

7bcC

D 0.0

9abC

D 0.0

5cC

0.10a

A 0.0

2 0.0

7 25

.94

* * *

Cora

tina

0.07a

bD

0.09a

CD

0.05b

cF

0.04c

dE

0.03d

E --

-- 0.0

2 0.0

6 43

.01

* * *

Itran

a 0.0

8aD

0.09a

CD

0.07a

EF

0.04b

E 0.0

2bE

-- --

0.03

0.06

48.59

* *

* Le

ccino

0.0

7cD

0.09b

cCD

0.11a

bBC

0.12a

B 0.1

0abC

--

-- 0.0

2 0.1

0 19

.63

* * *

Noce

llara

Mes

sines

e 0.1

1cC

0.15b

B 0.1

2cAB

0.1

8aA

0.15b

B 0.1

1cB

0.10c

A 0.0

3 0.1

3 22

.15

* * *

Nocia

ra

0.09a

CD

0.09a

CD

0.11a

BC

0.09a

C 0.1

0aC

0.10a

B --

0.01

0.10

8.45

* * *

Pend

olino

0.1

4aB

0.16a

B 0.0

9bcC

DE

0.08c

C 0.0

8cCD

0.1

1bB

-- 0.0

3 0.1

1 30

.42

* * *

Pich

oline

0.1

1aC

0.11a

C 0.1

0abB

CD

0.08b

cC

0.07c

D --

-- 0.0

2 0.0

9 19

.33

* * *

Sign

. * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

* --

-- --

--

Tabl

e IV

- Va

riatio

n in

OLL

conte

nt du

ring

olive

ripe

ning

for th

e dif

feren

t cult

ivars.

The

value

s rep

rese

nt the

mea

ns o

f nine

repli

cates

, thr

ee fo

r eac

h ha

rvest

year

(200

5-20

06-2

007)

S

D. T

he

total

mean

and

the

%RS

D we

re a

lso c

alcula

ted. M

eans

in th

e sa

me ro

w wi

th dif

feren

t low

erca

se le

tters

differ

sign

ifican

tly. M

eans

in th

e sa

me c

olumn

with

diffe

rent

uppe

rcase

lette

rs dif

fer

signif

icantl

y. In

both

rows

and c

olumn

s: * *

* (p

≤ 0.

001)

, * *

(p ≤

0.01

), *

(p ≤

0.05

), n.s

. (no

t sign

ifican

t).

OLL

2nd O

ct 17

th O

ct 1st

Nov

16

th N

ov

1st D

ec

16th

Dec

31

st D

ec

SD

Mean

%

RSD

Sign

. Ca

ssan

ese

2.96a

B 2.7

7cB

2.67d

B 2.8

1bB

2.26e

D 2.0

0fD

1.89g

C 0.4

3 2.4

8 17

.16

* * *

Ottob

ratic

a 1.4

4gE

1.62fD

2.1

7eD

2.30d

D 2.4

4cB

2.79a

C 2.7

0bB

0.51

2.21

23.24

* *

* Si

nopo

lese

1.22a

G 1.0

1deI

1.10b

cI 1.0

5cdH

0.8

9fI

0.97e

F 1.1

2abD

0.1

1 1.0

5 10

.26

* * *

Cora

tina

1.06b

I 1.2

5aH