mneme - UniPa€¦ · Leicester Art Gallery, ... recognise and decipher the content of pictures,...

Transcript of mneme - UniPa€¦ · Leicester Art Gallery, ... recognise and decipher the content of pictures,...

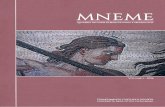

mneme

1

MNEMEquaderni dei corsi di beni culturali e archeologia

Antico e ModernoLaboratorio di ricerche trasversali II

a cura di Luna Figurelli

palermo2016

Editing fotografico: Filly Ciavanni

Immagine di copertina: Palermo, Palazzo Forcella, mosaico ‘di Ippolito’: il cacciatore, particolare (foto Aiosa).

MNEME. Quaderni dei Corsi di Beni Culturali e Archeologia

Direttore: Elisa Chiara PortaleComitato scientifico: Johannes Bergemann, Nicola Bonacasa †, Annliese Nef, Salvatore Nicosia,Vivien Prigent, Natascha Sojc.Comitato editoriale: Sergio Aiosa, Nunzio Allegro, Fabiola Ardizzone †, Oscar Belvedere,Armando Bisanti, Aurelio Burgio, Alfredo Casamento, Delia Chillura, Massimo Cultraro,Salvatore D’Onofrio, Monica de Cesare, Gioacchino Falsone, Franco Giorgianni, MauroLo Brutto, Leonardo Mercatanti, Vincenzo Messana, Giovanni Nuzzo, Pierfrancesco Palazzotto,Daniele Palermo, Simone Rambaldi, Cristina Rognoni, Roberto Sammartano, Luca Sineo.Coordinamento di redazione: Simone RambaldiProgetto editoriale e redazione web: Filly CiavanniDirezione e Redazione:Mneme. Quaderni dei Corsi di Beni Culturali e ArcheologiaUniversità degli Studi di PalermoDipartimento Culture e Societàviale delle Scienze, Edificio 1590128 PalermoContatti:[email protected]@unipa.it tel.: +39 091 [email protected] tel.: +39 091 23899549

La collana di monografie Mneme è pubblicata on line, sul sito: www.unipa.it/dipartimenti/beniculturalistudiculturali/riviste/mneme

Copyright 2016 © MNEME. Quaderni dei Corsi di Beni Culturali e ArcheologiaDipartimento Culture e Società, viale delle Scienze, Edificio 15, 90128 PalermoISSN 2532-1722 - ISBN 978-88-943324-0-7

I testi sono sottoposti a peer review interno a cura del Comitato scientifico e del Comitato editoriale

2016 - Anno 1 - Volume 1

Indice generale9 Premessa

di Elisa Chiara Portale

11 Introduzionedi Giuseppina Barone

15 Una caccia al cinghiale, mostri marini e temi nilotici nei mosaici pavimentali dell’ottocentescopalazzo Forcella a Palermo: tra suggestioni classiche e riproduzioni ‘in stile’ di Sergio Aiosa

47 Revival neoclassico e ideali risorgimentali nel programma decorativo della casa di unantiborbonico sicilianodi Fabiola Ardizzone

57 Anus ebria: l’estetica della vecchiaia nella storia del gustodi Alessia Dimartino

75 Vasi ‘all’antica’. Falsificazioni e rielaborazioni nella collezione vascolare del settecentescoMuseo di S. Martino delle Scale a Palermo di Rosanna Equizzi

87 La società italiana postunitaria nella pittura di Revival Classico di Luna Figurelli

103 L'invenzione della Sicilia antica. La protostoria siciliana nella storiografia italiana nazionalistae fascistadi Pietro Giammellaro

113 Le radici letterarie del mito nella pittura ‘neoclassica’ di Giuseppe Velasco di Mariny Guttilla

139 Settecento neoclassico nel Palazzo Reale di Caserta. Vanvitelli, Hamilton, Tischbein e ladecorazione ‘all’etrusca’di Margot Hleunig Heilmann

159 Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory by Thomas Uwinsdi Michael Liversidge

173 La corona rostrata oggi: appunti per una ricercadi Antonina Lo Porto

181 Dei milites. Esempi di foggia militare romana nella scultura barocca sicilianadi Salvatore Machì

195 Esempi di ispirazione all’antico nella produzione scultorea di Ippolito Buzzi, Nicolas Cordier,Pietro Berninidi Alessandra Migliorato

221 Giovanni da Cavino, ovvero storia di un onesto falsariodi Magda Modica

227 British Conservative Thought and the Classical Imagination, c. 1720-1820di James Moore

239 “È morto al posto mio”: da Elias Canetti ad Elio Aristidedi Salvatore Nicosia

249 “A city famed throughout the world”: Pompeii in 20th and 21st century fictiondi Joanna Paul

257 A pranzo con Matteo Della Cortedi Loredana Vermi

277 Abstracts

159

In 1831 Thomas Uwins, then an ambitious young painter who aspired to public recognition,sent his picture of A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory to London for the 1832 Royal Academy AnnualExhibition in London from Naples where he was living at the time (fig. 1). The canvas, now inLeicester Art Gallery, is generally regarded as an amusing picturesque scene that condescendinglycaricatures a contemporary aspect of Neapolitan life, albeit one with a very long history reachingback beyond the middle ages in Italy generally – the worship of images and their fashioning in artisanworkshops. The painting is, however, arguably far more complex and meaningful than at first itappears. As an Evangelical Protestant Thomas Uwins had been taught to regard Roman Catholicpractices and beliefs as idolatrous and superstitious, and the fierce debates and controversies aroundreligion and politics in Britain around the time his painting was publicly exhibited were such thatthe artist’s intention and the picture’s reception can hardly have been uncontentious. The picture’stitle and content, together with the lengthy description of the subject Uwins wrote for the exhibitioncatalogue, can be read in conjunction with English travel literature of the time, together withantiquarians’ studies of Roman and Roman Catholic cult practices, to disclose its politically freightedpurpose. It deploys references to the classical past within the framework of contemporary Italianreligious life to engage with current debates about Catholic Emancipation (the consequences of recentlegislation to permit Roman Catholic worship in public, and to allow Roman Catholics to hold publicoffices) and other issues and controversies in England. The painting thus demonstrates the complexresponses and receptions that British artists sometimes brought to bear on their vision of ancientand modern Italy, using references to the Roman pagan past to comment critically on the RomanCatholic present1.

What might a visitor to the Royal Academy in 1832 have made of A Neapolitan SaintManufactory by Thomas Uwins? How could the viewer have read the picture? What did the painterintend the viewer to read into it? To answer these questions the painting has to be considered in thelight of the politics of the time – that is, of the debates which had led up to the Catholic EmancipationAct of 1829 and which were still resonating in its aftermath, and of the contemporary controversiesraging around the Reform Bill which Parliament eventually passed and which received the RoyalAssent in 1833. In trying to estimate and understand the ways the picture may have been received byits viewers when it was on public display in 1832, the composition of that viewership, and the placethe Royal Academy occupied as an influential national institution that was part of the ‘establishment’,have to be taken into account.

The Royal Academy exhibition annually attracted an enormous attendance that made it part ofthe popular culture of the time2 (fig. 2). An artist like Uwins was therefore showing his work in a publicforum that addressed both an élite who were visually sophisticated, educated by experience and travel to

Michael Liversidge

Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory by Thomas Uwins

recognise and decipher the content of pictures, and a much wider audience whose visual comprehensionwas a simpler matter of description and narrative appeal. In the case of a subject painting such as thisa picture might attract attention because it entertained or amused by showing off an English view oflife abroad, or because it provoked a more obviously visceral response of some kind such as patriotism,prejudice or a patronising superiority towards foreigners. One reason why A Neapolitan SaintManufactory attracted the attention it did was precisely because Uwins skilfully negotiated hisaudience, painting a picture that anyone could understand and enjoy for its anecdotal detail andpicturesque characters, and which also very obviously represents the cupidity and credulity of foreignersand Roman Catholics in a way that expresses very clearly to any Protestant viewer the superior virtuesof reformed religion. By extension it implies that British (Church of England and Protestant) valuesare preferable to those of Roman Catholics. Privileging British belief and nationality renders it especiallyappealing to patriotic and popular prejudices. But beyond the purely popular level, the picture alsocontains a more erudite content through the references it makes to contemporary currents in scholarly

160

Fig. 1. Thomas Uwins, A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory (Royal Academy 1832). Leicester Arts and Museums Service.

MNEME 1

161

thinking and antiquarian studies relating the cult practices of ancient pagan (Roman) religion tomodern Roman Catholic ritual and practices3. So, to an informed viewer, the painting participated inan intellectual discourse about modern Italy, Catholic belief and the classical past which Uwinsexploited to make topical references to contemporary British religious and political issues – allusionsthat gave his picture resonant undertones of meaning with a specific relevance to the time and placewhere it was produced and displayed. It is important also to remember just how significant the RoyalAcademy’s annual summer exhibition was at the time as a site for making a political intervention byvisual means because of its dual nature as a place of high culture with a mass audience.

Reading a picture in this way using its contemporary context to reconstruct its reception raisesanother question: whether the artist intended such a reading. Reception (that is, how the meaning ofsomething was understood and interpolated) and intentionality (what the creator wanted it to mean)do not necessarily coincide: an artist might intend a picture to convey a particular message, but thatdoes not automatically mean that a viewer responds in the way intended. But with A Neapolitan SaintManufactory the artist’s intention was clearly signalled to the viewer by the catalogue entry whichincluded a descriptive, seemingly innocuous but in fact heavily loaded, explanatory note; and inaddition, reading other similar entries he added to exhibition pieces across his career as well as his lettersadds plenty of circumstantial detail to justify interpreting this and other pictures as politicised images4.

Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory Michael Liversidge

Fig. 2. George Scharf, Exhibition at the Royal Academy (London 1828). Museum of London.

Both the title and the catalogue explanation are revealingly critical if they are read from anineteenth-century perspective. ‘Neapolitan’ would conjure up to anyone who had read conventionaltravellers’ accounts of Naples from the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries a variety of derogatoryassociations: Naples and the Neapolitans were generally figured as the least honourable, congenitallydishonest, most depraved and fundamentally flawed of Italians5. ‘Saint manufactory’ implied toProtestant minds inferences that questioned the validity of Roman Catholic image worship as merelysuperstitious, and challenged Rome’s cult of saints – it was, after all, the Vatican itself that‘manufactured’ saints through its processes of beatification and canonisation and which sanctionedthe reverencing of images. Equally, at a time when the Industrial Revolution was in some enlightenedquarters beginning to be perceived more ambivalently as socially enslaving and degrading, the ideaof a ‘factory’ was itself becoming tainted6. Thus the general connotations of the title could easily havebeen construed by critics of the Roman Catholic church as referring to the falsities of doctrine and tothe oppression and exploitation of the faithful which, especially in their treatment of Italy, Britishtravel writers regularly observed.

Much the same sort of deconstruction can be applied to the text that Uwins provided as anaccompaniment to the image:

This shop is one of the most amusing things in the city. Here is displayed the whole machinery of Neapolitan devotion:crucifixes, Madonnas, saints, angels, and souls in purgatory. As I passed one day, two Capuchin friars were driving a hard bargainwith the saint-maker for a bunch of cherubs suspended from the ceiling, while some country-women brought their householdimages to be newly painted and repaired.

At first it reads as though it is a straightforward descriptive narrative of a personal recollection,but particular words and phrases strike a condescending and sceptical note when their literary nuancesare recognised for what they are, a carefully contrived litany of Roman Catholic offences againstdecent Protestant sensibilities. It becomes a passage loaded with heavy irony. This is a shop, not astudio – there is nothing artistic in the higher sense carried on here. It is amusing, in the sense of beingsomething to belittle and regard with cynical condescension. It displays the whole machinery ofNeapolitan devotion, a phrase that gratuitously dismisses as mechanical and empty the faith of thepeople represented, especially as it is followed by a catalogue of images of the kind that zealousProtestant divines had proscribed since the Reformation with particularly loaded references to theMarian idolatry (Madonnas) and the doctrine of purgatory that evangelical Anglicans objected tomost strenuously. Capuchin friars are often cited in travel books of the eighteenth and early-nineteenthcenturies as a paradigm of the parasitic orders that held a peasant population enthralled in povertyand constant fear of eternal damnation. And finally there are the simple country-women who havebrought their household images to be newly painted and repaired: ‘household images’ would invokein the minds of the classically educated the idea of pagan household gods, something quite familiarto a wider public, too, by the 1830s from popular accounts of the wonders of Pompeii; and perhaps itis not fanciful either to read the fact of their being brought in to be ‘newly painted and repaired’ as athinly veiled metaphor for Roman Catholic confession and absolution. Just as their images can be‘repainted and repaired’, so too can their souls be cosmetically renewed with a little religiousmakeover. Words and image are thus carefully construed to present a cynically prejudicial view ofCatholic faith and so create a sense of comforting superiority for an English Protestant viewer.

162

MNEME 1

163

In his commentary Uwins signals to his reader not only what is going on the picture but also,more importantly, how he wants it to be interpreted. There are details in the painting which need tobe read as attentively, and which corroborate the interpretation proposed here. A few examples willillustrate the point. The principal Capuchin friar, for instance, in his gestures, urgent expression anddominant attitude is eloquently contrasted with the resigned and weary characterisation of the imagemaker: a ruthless negotiator who drives a hard bargain, not an admirable model of ecclesiasticalcharity. His obviously corpulent, over-fed physique is another sign: a traditional way for Protestantsto ‘image’ Catholic priests who live off others rather than live by their vows of poverty that has a longhistory going back to the Reformation. A precedent that Uwins would surely have known well occursin William Hogarth’s famous Calais Gate in which a well-fattened friar salivates over and strokes amagnificent side of beef being carried to the kitchen by a ragged and emaciated French inn porter(fig. 3). On the floor of the workshop the images of souls engulfed in the flames of Purgatory lie nextto a water vase and wine bottle, with a Crucifix and religious print carelessly cast down beside them– possibly a visual encapsulation of a Protestant’s view of the falsity of the Roman Catholic doctrinesof Purgatory, substantiation and intercession.

Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory Michael Liversidge

Fig. 3. William Hogarth (engraving after), 'O the Roast Beef of Old England' (The Gate of Calais), 1749 (after the painting 1748).

Particularly interesting because they engage with another widely-held view of Catholic idolatrythat is frequently the subject of disapproving comment in nineteenth-century English travel booksare the references made to pagan classical, ancient Roman, antiquities in conjunction with thedevotional pieces in what is after all workshop supplying Christian, Roman Catholic images. Thereare several such details: classical heads on a shelf above the covered crucifix at top left, and a similargroup in the shadows at the back of the shop top right. Most tellingly of all is a nearly naked Venus,copied from the celebrated Venus Callipygos from the Naples royal collection at the time (nowin the Museo di Capodimonte), to the left of the covered crucifix. What is significant here is thehalf-length figure on a stand immediately to the left of Venus of a saved soul, with eyes turnedto heaven and arms spread in a gesture of devout sanctity. It is not an accident that his left handis where it is, sensually caressing the goddess. Uwins is surely here making a point about somethingthat is a regular refrain in his letters from Italy and throughout his later career in England after hereturned home to London, the hypocrisy as he saw it of the Roman Catholic church generally,and particularly in Italy. Travel books abound with stories of the sexual exploits of supposedlychaste nuns and their visiting confessors and supervisory priests, but in the overall context of thepicture there is more to this detail of the hand resting on a shapely woman’s intimate anatomy thana simple erotic irony.

Eighteen years after showing the Neapolitan Saint Manufactory, in 1850 Uwins exhibitedanother picture at the Royal Academy of a similar subject, but with a different, ironically chosen,title: Development. The painting itself is untraced, and were it not for the artist’s habit of addingdescriptive commentaries to his catalogue entries it would be impossible either to form anyidea of its appearance from the title, or to recover its meaning. Evidently, however, it showedanother workshop of the same kind, as the catalogue note makes clear: “There is nothing I knowto compare with the image shops and saint manufactories of Naples; here is the perfectionof development. Diana of the Ephesians must yield to the modern Queen of Heaven”. In otherwords, there is a seamless progression from the pagan beliefs and practices, and idols, of theancient Romans to the Roman Catholic church that followed them. The cult of Diana simplybecame the cult of the Virgin Mary7. Household gods become household images. Imperial Romebecomes Papal Rome.

Where did Uwins derive this idea from? The answer to this question can be found in thework of the antiquaries and scholars who, at least since the seventeenth century, had been concernedwith recovering the evidence of ancient cult ritual and practices. Occasional discoveries ofRoman sanctuary sites, identified from their votive deposits, had led to a progressively greaterknowledge of religious cults in the ancient world. An early example of this kind of enquirywas the recognition in 1637 of the sanctuary of Diana at Nemi, a place subsequently muchvisited and remarked upon by travellers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Various ex votoremains had been found – terracotta figurines, anatomical parts, votive heads of the deity – leftthere by those who had sought Diana’s favour to cure an ailment or to obtain her patronage.Antiquarians’ speculations about Roman religious practices and popular superstitions werefuelled by reading classical authors and historians; and since the rediscovery of Pompeii the topichad received a further impetus from the quantities of household images found in the shops,houses and villas of the ancient city8.

164

MNEME 1

165

Thomas Uwins must have been aware of the most recent, and most comprehensive, scholarlytreatment of the whole subject which appeared in 1823, two years before he set out to live andwork in Italy to perfect his art. This was the magisterial study by the Reverend J.J. Blunt, Vestigesof Ancient Manners and Customs, discoverable in Modern Italy and Sicily, in which the authorassembled a vast array of evidence from antiquarian studies, recent archaeology and classicalscholarship to account for contemporary Italian customs, many of which were religious practicesor traditions. Here is a monumental study of ancient cults appropriated by an English, Protestantclergyman to prove the essentially profane and pagan origins of so much Roman Catholic worship.Images, relics, ritual, liturgy and even vestments are all to some degree presented as carrying onan unbroken tradition from the ancient (and therefore by definition decadently pagan) Romans.This view was commonplace in the nineteenth century, as is evidenced by the frequent referencesto it in numerous popular travel books and accounts of life in Italy9.

Thomas Uwins was rabidly anti-Catholic and deeply alarmed at the dangers to the Britishway of life and constitution that, to him as to others, Roman Catholicism presented10. When Uwinspainted his Neapolitan Saint Manufactory the country was caught up in the controversies stillreverberating from the Catholic Emancipation Act, passed by Parliament in 1829 after a long andheated political campaign which had carried on throughout the 1820s. The debate was raging whenUwins had set off for Italy in 1824, and when he returned after seven years the political agenda hadmoved on to issues of constitutional reform, some of them arising from the liberalisation that CatholicEmancipation inaugurated, others focussed around related political developments in Ireland (itsoverwhelmingly Roman Catholic population ruled by the British Crown with a Viceroy in Dublin).For thirty years the question of Catholic Emancipation had been at the forefront of domestic politics,not least “because of its intimate connection with the endemic unrest in Ireland” where earlier lawsdebarring Catholics and Dissenters (anyone, that is, refusing to acknowledge the church over whichthe English Crown presided) from holding any public office were perceived as the principalinstruments of English oppression11. The Emancipation Act effectively enabled the Roman CatholicChurch to establish itself openly in the community (throughout the United Kingdom, not only inIreland), to build its churches and cathedrals, and to found religious institutions; it aroused fiercepassions because Catholicism was regarded with deep suspicion as an alien religion that exerciseda controlling power over its adherents and owed its allegiance to a foreign authority (the Papacyin Rome) that was both spiritual and temporal. As the politician and later Prime Minister RobertPeel asked in Parliament, “Could any man acquainted with the state of the world doubt for a momentthat there was engrafted on the Catholic religion something more than a scheme for promotingmere religion?...Could he know what the doctrine of absolution, of confession, of indulgences was,without a suspicion that these doctrines were maintained for the purpose of establishing the powerof [one] man over the hearts and minds of men?”. Few issues aroused so much prejudice, hostilityand suspicion in some quarters in the 1820s as the perceived threat from a Roman Catholicrevival, and it seemed all the greater because it was associated with the prospect of possible Irishrebellion.

In this context the appearance in the Royal Academy and British Institution exhibitionsin the 1820s of pictures of Irish peasants and their Italian counterparts assumes an explicitlypolitical dimension. One such example is Charles Eastlake’s 1827 Italian scene in the Anno Santo,

Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory Michael Liversidge

pilgrims arriving in sight of Rome and St Peter’s: Evening (fig. 4). What might now be mistaken fora straightforward picturesque genre subject that romanticises the simple piety of Neapolitan pilgrimswas in its day a much more resonant image, invoking ideas of Catholic credulity and the Romanchurch as a corrupting influence. In exactly the same way, pictures of Irish peasants could be takento represent a constant and potentially subverting threat to the British constitution from populationthat predominantly professed a religion controlled by an alien, Papal, authority.

Religious controversy remained a source of contention long after the Catholic EmancipationAct became law. It opened the way to further constitutional changes, and was one of the factors thatled to the Reform Bill of 1832. Certainly a connection between religion and reform was made byThomas Uwins, who in a letter of 5 June 1832 links a dramatic moment in the Reform Bill’s progressin Parliament with a painting by David Wilkie on display in the same Royal Academy exhibitionwhere his own Neapolitan Saint Manufactory was on show. His comments clearly demonstrate howa subject taken from an episode in the nation’s religious – specifically Protestant Reformation – historyhad a political significance and symbolism for the present. Writing to his friend and fellow artist inRome, Joseph Severn, Uwins expresses a deeply conservative, reactionary view that equates thegovernment’s Reform Bill with the erosion of British Protestant values, implicating by associationthe re-emergence of the Roman Catholic presence in British politics with a creeping subversion ofthe proper national constitutional order. He does so by pointedly contrasting the furore that resulted

166

Fig. 4. Charles Eastlake (engraving after), Italian Scene in the Anno Santo, pilgrims arriving in sight of Rome and St Peter's,Evening (engraving 1842 after 1827 painting exhibited at Royal Academy 1828).

MNEME 1

167

Titolo Autore

when the legislation (which Uwins deplored) was temporarily delayed because the House of Lordsdefeated the government in Parliament (itself a potent symbol of the liberties won from Rome byHenry VIII, Elizabeth I and the 1688 Glorious Revolution) with the painting by David Wilkie of adramatic episode in the Scottish Reformation when a Protestant preacher confronted the arbitrarypower of a Roman Catholic monarch, Mary Queen of Scots, and of the Papal Legate (fig. 5):

…I must tell you of the Exhibition, an exhibition opened under the most inauspicious of circumstances. The very day wasthat unfortunate one in which the ministers were defeated in the House of Lords, and the whole nation thrown into the most frightfulconfusion. Who could think of pictures? Had anyone ventured to name the arts of peace on this day of anarchy, he would havebeen marked out as a traitor to Reform, and hunted down as an enemy to his country. At any other, Wilkie’s John Knox wouldhave been a point of interest round which all the intelligence of the country would have assembled. It is, in truth, a noble work…The power of the preacher’s eloquence, and the growing strength of the [Protestant] party, is abundantly displayed; not merely inthe determined countenances of his followers and adherents, and in the devoted expression of the multitude, who seem to bedrinking in the truths that he utters, - this was not sufficient to accomplish Wilkie’s powerful conception of the subject. To makethe conflict more terrific, he has brought the Catholic bishop into the church, accompanied by an armed man, who stands preparedto shoot the preacher at the word given…the picture may be considered a complete history of the Reformation…12

Fig. 5. David Wilkie, The Preaching of John Knox before the Lords of the Congregation 10 June 1559, 1832 (reduced version ofRoyal Academy exhibit 1832). National Galleries of Scotland.

The events Uwins described had happened in May. When he wrote the letter on 5 June 1832the government had succeeded in overturning its defeat and the Reform Bill had finally passed theHouse of Lords. He ends his letter on a gloomy note: “The whole talk is of the anticipated strugglebetween the people and the aristocracy. The Reform Bill was carried last night in the House of Lords,by a majority of forty-seven”. Changing the constitution he felt would undermine the authority of theestablishment and lead to political and religious decline. The conjunction in his letter of theReformation (John Knox’s preaching against the Roman Catholic church) and the Reform Bill issurely no accidental coincidence. The fact that these two anti-Catholic paintings appeared on theRoyal Academy’s walls in the same exhibition, Uwins’s Neapolitan Saint Manufactory and Wilkie’sJohn Knox Preaching, demonstrates how the annual summer show could be turned to politicalpurposes. Uwins and Wilkie knew each other well having met in Italy in 1826, and very possibly theywere aware of the subjects they were each working on in 1831, so it is conceivable that theirtwo pictures at the 1832 Royal Academy exhibition were deliberately intended to complement eachother13. David Wilkie’s picture takes a subject from sixteenth-century British history to commenton recent and current political events. In A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory Thomas Uwins deploysnineteenth-century British classical receptions and a critical view of modern Italy as a means ofalluding to contemporary religious debates at the centre of current affairs. By comparing the modernRoman Catholic church with ancient Roman pagan practices he was using the classical past in apolitical context and for a purpose that makes his picture much more than what at first it seems,a simple or amusing anecdote from Neapolitan life.

168

MNEME 1

169

Note

1 For British responses to in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and artistic and literary appropriations of antiquity to commenton modern and Roman Catholic practices, see Liversidge, Edwards 1996 and Powell 1998.

2 Solkin 2001.3 In a letter written from Italy by Uwins in 1826 the artist clearly states his prejudices against Roman Catholicism: …I cannot

reconcile myself to living in a Catholic country…where, not being able to speak my feelings, robs me of that consciousnessof integrity that is necessary to the moral existence of a human being…to be silent seems like hypocrisy. Uwins 1858, 298-299.For British receptions of modern as degraded by centuries of Roman Catholic oppression, see Cecilia Powell, Paintersof Modern Life, in Powell 1998, n. 2, pp. 39-55.

4 Royal Academy of Arts Exhibition Catalogue, London 1832, No 239; the painting had the distinction of being shown in theGreat Room (the gallery shown in George Scharf’s 1828 watercolour, Fig. 2), reserved for those performances considered ofmost consequence by the Selection Committee...

5 English travel books of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries abound with adverse observations about Neapolitans, as do theletters written home by visiting artists such as Thomas Uwins and Samuel Palmer from the 1820s and 1830s. Charles Dickensin Pictures from Italy (1846), is typical of the general attitude, echoing earlier writers (for example William Blunkett [1785]:I never saw a rougher, more unpolished people both in countenance and in manners in all my life. They have a vulgarity andignorance about them which is particularly disgusting). Uwins observed in one of his letters that …Neapolitans seem alwaysbent on some impudent knavery…they seem only happy while they are practising some trick to impose upon you. Cheatingappears the business of their lives. They would not think they had done their duty if they were to act honestly… (29 April 1825).Uwins 1858, pp. 254-255; 29 April 1825.

6 By the 1820s industrialisation and manufacturing cities were beginning to attract critical reactions from those who saw them asagents of exploitation and oppression. See Klingender 1947.

7 The earliest politicised representations of specifically Roman Catholic priests and monastic or mendicant orders as verminousparasites are to be found in the explicitly Protestant woodcut illustrations designed by Hans Holbein the younger in the 1530sfor Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s Catechism: see Strong 1969.

8 The reference to Diana of the Ephesians would be recognised by the reader as alluding to the New Testament Acts of the Apostles,chapter 19, verses 24-41, which recounts the events during ’s visit to and the riot he caused among the worshippers of Dianawhen he preached there. The passage was especially significant for Protestants who used it from the Reformation to supporttheir arguments against Roman Catholic images and idolatry. The episode describes how the Ephesians were incited byDemetrius, a silversmith, who made silver shrines for Diana, who spoke out against Paul who not alone at , but almost throughout…has persuaded and turned away many people, saying that there be no gods that are made with hands. The text was used todenounce the making of images by the early reformers, and later to demonstrate that Roman Catholic image-making was heirto pagan classical votive cults.

9 For early interest in classical cult sites in , see Fenelli 1975; Blagg 1985; Ginge 1993. Probably the most widely circulatedexample of an ancient votive cult assimilated into contemporary Roman Catholic cult practices in eighteenth and nineteenthcentury British antiquarian studies, apart from recent discoveries made at , was the celebrated example published by Sir WilliamHamilton and Richard Payne Knight. Hamilton had learned of a practice that survived in the remote town of Isernia in Abruzzowhen the feast of Saints Cosmas and Damian was celebrated which he concluded was the Cult of Priapus in as full vigour asin the days of the Greeks and Romans…. The cult consisted of an ancient festival at which votive offerings representing themale organs of generation were taken by women to the church and offered with dedications to St Cosmas. What Hamiltondescribed was a phallic cult that he claimed had continued uninterrupted from pagan antiquity and which had become a Christianreligious ritual, a rather bizarre example of what was a widespread belief among many observers of life in Italy that Catholicimage-worship and the practice of making offerings at altars and shrines (including presenting models of afflicted limbs andbody parts in the hope of a cure) were directly carried on from Roman rituals. Hamilton, Payne Knight 1786.

Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory Michael Liversidge

10 Typical of the perception that Roman Catholic ceremony and liturgy had originated in ancient Roman ritual is the Reverend M.Hobart Seymour whose A Pilgrimage to Rome published in 1848 was written to correct the catholicising tendencies of theAnglo-Catholic Oxford Movement which advocated adopting a more colourfully ornamented and theatrical form of worship inthe Protestant Church of England services to counter the attractions of Roman Catholic spectacle: There are many personswhose tastes and studies have always been allied to the classics. On visiting the present city of Rome, they discern … in all thereligious ceremonies and customs of the place, a striking similarity to the ceremonies and customs of the ancient and heatheninhabitants, as striking as that which they find in the walls, the baths, the temples, the arches and other relics of the past. Theyconceive that the ruins…are not more certainly the remains of edifices of heathen times, than are the religious ceremonies,opinions and customs of the place, the remains of the religion of heathen times. Catholic ritual had originated with theappropriation of pagan practices: It was the fruitful source, from which issued a large portion of the evils and corruptions thatnow defile the Church of Rome. Her invocation of saints, her worship of images and pictures, her pomps and ceremonies, andall her priestly vestments, have had their birth in a system which has but changed the name, but not the nature, of the oldreligion. The things that were worshipped in pagan times under one name, are now in Christian times worshipped underanother…The name of Paganism has faded before the name of Christianity; the names are changed; but the religion – theworship – is essentially the same. In his 1855 novel The Newcomes, William Makepeace Thackeray has one of his charactersrecall witnessing the Christmas Mass in St Peter’s which he …looked on as a Protestant. Holy Father on his throne or in hispalanquin, cardinals with their tails and train-bearers, mitred bishops and abbots, regiments of friars and clergy, relics exposedfor adoration, columns draped, altars illuminated, incense smoking, organs pealing, and boxes of piping soprano, Swiss guardswith slashed breaches and fringed halberts…and yonder old statue of Peter might have been Jupiter again, surrounded bya procession of flamens and augurs, and Augustus as Pontifex Maximus, to inspect the sacrifices… (Thackeray 1890, III,pp. 355-356).

11 His prejudices were given typical expression in a letter he wrote in 1841 to John Townshend describing his disgust at witnessingthe consecration of the new Roman Catholic Cathedral in Birmingham, describing Rome as the city where Superstition sitsenthroned, and Blasphemy claims the character of holiness: I witnessed in Birmingham the most alarming inroads made by theChurch of Rome on the faith bequeathed to us by Christ and his Apostles…in good truth everything dear to us is sadly threatenedon all sides… (28 June 1841). Uwins 1858, p. 111).

12 For a nineteenth-century, politically Protestant, view of the consequences of the constitutional changes of the 1820s and 1830son British society and national institutions, see Johnson 1868. Hinde (1922) provides a useful survey of the religious and politicalperspectives from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries in British and Irish history.

13 Uwins 1858 (5 June 1832). The painting by Wilkie (Royal Academy Annual Exhibition, 1832, p. 134) is now in the Tate BritainGallery collection, London. Its political resonance with contemporary religious controversy is reinforced by its having beenbought by Robert Peel.

14 Thomas Uwins wrote of his meeting with Sir David Wilkie, by then one of the Royal Academy’s most senior and criticallyacclaimed figures and a favoured painter of George IV, in a letter home from Naples in 1826: Since last I wrote, some mostdelightful things have happened to me, and amongst the most delightful is the having had much communication and intercoursewith Wilkie, whose visit here has been to me a stimulus and encouragement that I scarcely expected. I have not only shown himwhat I am engaged on, but he has been with me to the Palazzo Acton to see those pictures that I have finished and delivered.The things I have done here I believe have a little surprised him. He hardly knew me as an oil painter. I used to fancy at onetime that he was very cold and unfriendly...his conduct has been most friendly and most kind. I have been a three days’ excursionwith him to visit the ancient temples of Paestum, taking in our return to the city of Pompeii and the museum at Portici; andanother separate journey to the top of Vesuvius and Herculaneum… (14 March 1826). Uwins 1858, p. 299.

170

MNEME 1

171

Bibliografia

BLAGG 1985 = T. Blagg, Cult practice and its social context in the religious sanctuaries of Latium and SouthernEtruria, in C. Malone, S. Stoddart (a cura di), Papers in Italian Archaeology, Oxford 1985 (“BAR InternationalSeries”, 246).

FENELLI 1975 = M. Fenelli, Contributo per lo studio del votivo anatomico: I votivi anatomici di Lavinio, in «ArchCl»25, 1975, pp. 206-252.

GINGE 1993 = B. Ginge, Votive deposits in Italy: new perspectives on old finds, in «AJA» 6, 1993, pp. 285-288.HAMILTON, Payne Knight 1786 = W. Hamilton, R. Payne Knight, An Account of the Remains of the Worship of

Priapus lately existing at Isernia, in the Kingdom of Naples: in Two Letters, One from Sir William Hamilton,K.B., His Majesty’s Minister at the Court of Naples, to Sir Joseph Banks, Bart., President of the Royal Society.And the other from a Person residing at Isernia: To which is Added, A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus,And its Connexion with the mystic Theology of the Ancients, London 1786.

HINDE 1992 = W. Hinde, Catholic Emancipation: a shake to men’s minds, Oxford 1992.HOBART SEyMOUR 1848 = M. Hobart Seymour, A Pilgrimage to Rome, London 1848.JOHNSON 1868 = D.D. Evans Johnson, The results of Emancipation, Dublin-London 1868. KLINGENDER 1947 = F. Klingender, Art and the Industrial Revolution, London 1947.LIVERSIDGE, EDWARDS 1996 = M. Liversidge, C. Edwards (a cura di), Imagining Rome: British Artists and Rome

in the Nineteenth Century (Catalogo della Mostra, Bristol 1996), Bristol-London 1996.POWELL 1998 = C. Powell, Italy in the Age of Turner. ‘The Garden of the World’, London 1998.SOLKIN 2001 = D. Solkin, Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions 1780-1836, London 2001.STRONG 1969 = R. Strong, Holbein and Henry VIII, London 1969.THACKERAy 1890 = The Works of William Makepeace Thackeray, London 1890. UWINS 1858 = S. Uwins, A Memoir of Thomas Uwins R.A. With Letters to his brothers during seven years spent

in Italy, London 1858.

Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory Michael Liversidge

287

Idols Ancient and Modern: A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory by Thomas Uwins

The painting A Neapolitan Saint Manufactory by Thomas Uwins may at first sight look like aninnocuously humorous, anecdotally parodic caricature of Italian customs and characters painted for theamusement of an English audience, but to regard it as no more than an entertaining ‘genre’ picture wouldbe to miss its more serious political meaning.

Considered in the context of the hotly contested issues of Catholic Emancipation, the Reform Actand the perceived threat from nascent nationalist currents in Ireland, the imagery can be interpreted as avisual commentary on contemporary British politics and religious affairs. As a profoundly committedEvangelical Anglican horrified by the prospect of rampant Roman Catholicism this paper argues thatThomas Uwins was politically motivated in choosing the subject, and that its public exhibition at theRoyal Academy of Arts in London in 1832 was deliberately timed and intended to make an explicitreference to the national danger which those who had opposed Catholic Emancipation, the consequencesof which were still a subject of lively debate and protest, and who were now opposing the Reform Bill,were convinced the country faced. By drawing on recent and contemporary studies which equated ancientRoman pagan cults with modern ‘idolatrous’ Roman Catholic practices, often also commented upon intravel accounts of Italy written at the time, Uwins deployed an iconography which an informed readerof his picture and its catalogue description would readily understand and relate to current political affairsin 1830s England.

Michael LiversidgeEmeritus Dean

University of BristolFaculty of Arts − History of Art Department

MNEME 1 Quaderni dei Corsi di Beni Culturali e Archeologia

Finito di editareDipartimento Culture e Società

Università di Palermo Dicembre 2016

Mneme. quaderni dei Corsi diBeni Culturali e Archeologia

Dipartimento Culture e SocietàUniversità degli Studi di Palermoviale delle Scienze, Edificio 15 - 90128 Palermo

ISSN 2532-1722 - ISBN 978-88-943324-0-7

www.unipa.it/dipartimenti/beniculturalistudiculturali/riviste/mneme