ISSN: COMITATO DELLA PUBS/A27.pdf1952), the demographic legacy of early waves ofimmigration wasstill...

Transcript of ISSN: COMITATO DELLA PUBS/A27.pdf1952), the demographic legacy of early waves ofimmigration wasstill...

ISSN: 0016-6987

COMITATO ITALIANO PER LO STUDIO

DEI PROBLEM! DELLA POPOLAZIONE

G E N U SRIV1STA FONDATA DA CORRADO GINI

EDITA SOTTO IL PATROCINIO DEL

CONSIGLIO NAZIONA(-E DELLE RICERCHE

CHARLES HIRSCHMAN DOROTHY FERNANDEZ

THE DECLINE OF FERTILITYIN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA

Estratto da:

Volume XXXVI-n.1-2 GENNAIO/GIUGNO 1980

SPEDIZIONE IN ABBONAMENTO POSTALE-GRUPPO IV (70%).SEMESTRALE

93

CHARLES HIRSCHMAN DOROTHY FERNANDEZ

THE DECLINE OF FERTILITY IN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA ()

INTRODUCTION

Modem demographic transitions have begun to emerge in a number ofdeveloping countries, particularly in Asia. While little definitive evidence is availablefor the giant Third World countries (Mauldin, 1976), sustained and substantialfertility declines have been documented and analyzed for Taiwan (Freedman and

Muller, 1967; Freedman, Hermann and Sun, 1972; Freedman, et al., 1974;Freedman, et al., 1977), Korea (Cho, 1971, 1973), Singapore (Saw, 1975); andother Asian nations (Retherford and Cho, 1973). This paper adds to this growingliterature on modem Asian demographic transitions with a detailed analysis offertility trends and differentials in Peninsular Malaysia from 1947 to 1974.

During the last decade of colonial rule from 1947 to 1957, fertility levelsin Peninsular Malaysia were quite high with a crude birth rate in the middle 40s.There are some signs that fertility might have actually increased during the earlyand mid 1950s. But then a rather amazing decline began which brought the crudebirth rate from 46 in 1956 to 31 in 1974. This rapid decline has occurred amongall major ethnic communities and is attributable to both a rapid rise in the averageage at first marriage and declines in marital fertility rates. Changing age structurehas not been a major factor. While prior research has examined various aspectsof Malaysian fertility over this period (Ariffin and Palmore, 1973; Caldwell, 1963;Cho, 1970; Cho, Palmore and Saunders, 1968; Cho, Tan and Shantakumar; Palmo-re and Ariffin, 1969; Palmore, Chander and Femandez, 1975; Saw, 1966, 1967b),this paper will present the first comprehensive examination of annual fertilitychanges and differentials for both the pre-decline (1947-1957) and rapid decline

(1958-1974) eras.These findings for Peninsular Malaysia are important in a broader compara-

tive perspective both for the common features of fertility decline shared with other

societies, and for some unique differences. The importance of rising age at firstmarriage as a key element in the process is different from that of other East Asian

(*) This research is based upon vital statistics that are collected and published by theRegistration Department of Malaysia and the Department of Statistics of Malaysia. We are

most grateful for the cooperation and encouragement of Mr. R. Chander, Chief Statistician ofMalaysia. The authors would like to thank James Dobbins, Avery Guest and Ronald Rindfussfor their constructive comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Research assistance and

computer programming were most ablely provided by Karen Bothel, Russell Hayman, JeanWan, John Zipp and especially by Sharon Poss. The authors also thank Teresa Dark for typing

the manuscript. The research project, of which this paper is a part, has been supported bygrants from The Ford Foundation and The Duke University Research Council.

94

Chinese societies which already had a relatively late age at marriage pattern. Ma-laysian fertility has declined not only among the large Chinese minority population,but also among the Malay and Indian communities. This suggests that recent fer-tility declines in Asia have not been solely limited to predominately Chinese culturepopulations. These trends and patterns will be investigated in detail after a briefintroduction to Malaysian society and demographic data.

PENINSULAR MALAYSIA: PLURAL SOCIETY AND SOURCES OF DATA

Prior to the formation of Malaysia in 1963, Peninsular Malaysia was

known as Malaya. Malaya became an independent country in 1957 after a longperiod of British colonial rule. In 1970, Peninsular Malaysia had 84 percent (or 8.8million) of the total population (10.4 million) of Malaysia (Department of Statis-tics, 1973:52-55). The other part of Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak, are sparsely set-tled states on the island of Borneo, separated from Peninsular Malaysia by over 400miles of the South China Sea. Because of a lack of comparable data, our analysisis limited to Peninsular Malaysia.

From the middle of the last century until the early 1930s, internationalimmigration from other regions of Asia was the primary source of populationgrowth in Peninsular Malaysia (Jackson, 1961; Sandhu, 1969; Saw, 1963; Smith,1964). Attracted by the opportunities for wage labor in the growing rubber andtin sectois of the colonial economy, the immigrant Chinese and Indian communi-ties in Peninsular Malaysia grew to be almost as numerous as the indigenous Malaypopulation. With the cessation of international immigration after World War II,natural increase among all ethnic communities became the primary source ofgrowth and the ethnic composition has remained fairly stable. In the 1970 Censusof Population,. 53 percent of the population was classified as Malay, 36 percentChinese, 11 percent Indian, and a small traction of one percent as Others (Depart-ment of Statistics, 1973 62). These ethnic divisions, populare known as races or

community groups, are based upon a combination of national-origin, language,religious, and cultural criteria. In censuses and surveys, individuals are asked towhich "community group" they belong. There are rather wide cultural and socio-economic divisions between the ethnic communities that have narrowed onlymodestly over the years. Chinese have a more diverse occupational structure and a

much higher proportion in urban areas than does the Malay population, which ispredominately rural and agrarian. The small Indian community is intermediateon most socioeconomic measures, with a large minority engaged as wage laborerson agricultural plantations (for a review of ethnic socioeconomic differences, seeAries, 1971; and Hirschman, 1975). This analysis of fertility trends will comparethe pattern of. fertility change by ethnic groups in Peninsular Malaysia. As willbecome clear later, the overall structure and trend in national fertility is a weightedaverage of rather different fertility levels and changes among the three ethniccommunities.

95

During British colonial rule, routine gathering of demographic datathrough periodic censuses and the registration of vital events was established in thelate 19th Century (United Nations, 1962 4244). For each year from 1946 to thepresent, vital registration data on births and deaths for all of Peninsular Malaysiahave been published in the annual Reports of the Registrar-General and later inannual publications of the Malaysian Department of Statistics. Saw (1964) esti-mated through indirect methods that birth registration was about 10 percentincomplete from 1947 and 1957, and Cho, et al. (1969) reported that birth regis-tration was almost complete in the late 1960s. These evaluations suggest that thequality of the data are sufficient for detailed demographic analysis (also seeHirschman, 1971, 1974). To the extent that completeness of registration hasimproved over the years, the decline in measured fertility rates will be an underes-timate of the true decline.

In order to compute annual vital rates with registration data, we haveconstructed a consistent series of annual population estimates by age, sex, andethnic community for the intercensal periods, 1948 to 1956 and 1958 to 1969(Hirschman, 1978). These intercensal estimates are based upon interpolations ofadjusted census figures and vital registration data. The single largest adjustment wasto use 1970 Census data, corrected for underenumeration as reported in the Post-Enumeration Survey. This adjustment increases the 1970 population by fourpercent (and indirectly for the years prior to and after 1970) (1). The populationfigures for 1971 to 1974 are consistent postcensal estimates prepared by the Ma-laysian Department of Statistics and published in their Vital Statistics publication.In addition to the annual vital statistics data, this study also analyzes fertilitytrends using census data on the number of children ever born by age of motherfrom the 1947, 1957, and 1970 Population Censuses.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE EMERGING DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION

An overview of the time path of the Malaysian demographic transitioncan be observed in Figure 1 which graphs three basic demographic measures from1947 to 1974: the crude birth rate, the general fertility rate, and the crude deathrate. While erratic fluctuations, especially early in the time series, may be due tovariations in the completeness of registration of vital events, the downward courseof all rates is unmistakable. Assuming that completeness of birth and death registra-tion has improved over the years, the measured trends are probably underestimatesof the true declines (2).

(1) This adjustment wfll slightly lower fertility rates for 1970, but since the pre-1970population estimates are interpolations, based partially on the 1970 census, the effect on thetrend is slight.

(2) While the population denominators have been adjusted slightly upwards, theseare too small to have affected the rates appreciably.

96

FIGURE TRENDS IN THE CRUDE BIRTH RflTE, GENERRL FERTILITY RRTE,CRUDE DEPTH RRTE: PENINSULRR MRLRYSIfl, 917 \W

In the late 1940s, mortality rates were very high with a crude death ratefluctuating around 15, but beginning in the early 1950s, a consistent downwardtrend in mortality began and continued for the next 25 years with only a few ex-

ceptional years with upward movement. By 1960, the crude death rate was slightlyabove 9 per thousand and in 1974, the crude death rate was approaching thealmost unbelievable level of 6 per thousand. Of course, such an extraordinarily lowcrude death rate is partially a reflection of the very youthful age structure of thecountry.

The time-series in fertility rates is similar to that of mortality except fora lag of about 7 or 8 years. The crude birth rate fluctuated above 40 until the late1950s, when a downward trend began. Looking at the more refined general fertili-ty rate, it appears that there was an increase in fertility from 1949 to the mid1950s, but the pattern is somewhat erratic. A speculative interpretation to bepursued in a following section of this paper is that the prosperous years of theearly 1950s contributed to higher fertility levels.

97

The decline in fertility from the late 1950s to the mid 1970s is ratheramazing. The crude birth rate fell from 46 in 1957, to 40 in 1962, to 35 by 1967,and to 31 in 1974. Over the same period the general fertility rate dropped from 210to 130 births per thousand women in the reproductive ages. Given that improvingvital registration has probably moderated the measured decline over the years, thedownward trend is even more impressive. In the rest of this paper, this trend andethnic variations in the trend will be examined in more detail through the basicdemographic techniques of refined fertility measurement and decomposition ofvital rates. Our interpretation of the trend will be tentative and secondary to theprimary objectives of measurement and description. But since changes in age andmarital composition are so closely linked to shifts in fertility, our analysis willbegin with a consideration of change in these two crucial variables. Our subsequentanalysis will measure their effects on the observed fertility decline.

BACKGROUND FACTORS: AGE AND MARITAL COMPOSITION

Changes in Age-Sex Structure, 1947-1974

Until recently, the population of Peninsular Malaysia had a peculiarage-sex structure, particularly among the Chinese and Indian populations. This wasthe result of the heavy volume of immigration during the first several decades ofthe 20th century. Immigration (and corresponding emigration) contributed to a

disproportionate share of the population in the working adult years, and an unbal-anced sex ratio, dominated by men. While the considerable immigration of Chinesewomen during the 1930s helped to balance the sex-ratio among Chinese (Smith,1952), the demographic legacy of early waves of immigration was still evident inthe post-war period. In 1947, there were 123 males per 100 females among theChinese population, and 148 males for every 100 females among the Indian popula-tion, compared to a relatively normal sex-ratio of 99 among the Malay population(Hirschman, 1978, Appendix Table 1). Consequently, the proportion of "womenin the childbearing years to the total population" was considerably smaller amongthe Chinese and Indian communities than among the Malay population. Thechanges in this proportion (women 1549 to the total population) from 1950 to

1974 are shown in table 1.For the total population (all three ethnic communities), there was rel-

atively little change in the age-sex structure (relative proportion of women in thechildbearing years) through the middle of the 1960s. The fraction of women inthe oldest category (35-49) decreased a bit, while the youngest women (15-24)increased their share marginally, thus making the overall age structure somewhatmore favorable to higher fertility. But as the large postwar birth cohorts beganentering the childbearing years in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the fraction of

98

TABLE 1

Women in the ChUdbearine Ages as a Percentage of the Total Population(Both Sexes) by Age and Ethnic Community: Peninsular Malaysia, 1950-1974

Percentage of total (both sexes) population

1950 1958 1966 1974

Percentage change1950- 1958- 1966-1958 1966 1974

Total women15-2425-3435-49

Total, 15-49No. of women

(000)

Malay women15-2425-3435-49

Total, 15-49No. of women(000)

Chinese women15.2425-3435-19

Total, 15-49No. of women(000)

Indian women15-2425-343549

Total, 1549No. of women(000)

8.66.56.9

21.9

(1,148)

9.47.77.4

24.5

(630)

8.35.67.5

21.4

(431)

7.96.56.2

20.7

(120)

8.86.46.6

21.8

(1,439)

9.37.26.8

23.3

(762)

8.75.66.5

20.8

(513)

7.55.55.9

19.0

(141)

8.96.36.3

21.6

(1,794)

8.86.56.8

22.2

(958)

93.6.25.8

21.3

(642)

8.05.65.5

19.2

(171)

10.76.46.5

23.5

(2,377)

10.66.26.6

23.4

(1,257)

10.76.76.4

23.8

(856)

11.15.76.0

22.9

(244)

29.624.820.4

25.3

25.518.817.6

20.9

28.523.05.5

19.0

20.38.7

21.5

17.0

27.324.121.6

24.6

25.119.532.9

25.7

30.434.69.8

25.1

29.022.211.0

21.3

45.622.324.2

32.4

48.918.820.3

31.2

37.929.230.3

33.3

67.420.730.6

43.0

Source: Adjusted 1947,1957 and 1970 census data, intereensal interpolations, and postcensalestimates, see Hirschnian (1978), Appendix tables.

99

young women increased sharply. In fact, from 1966 to 1974, the number of youngwomen 15-24 almost doubled (45.6%), while the total number of women in thechildbearing years (15-49) grew by almost a third (32.4%).

While the age-sex structures of the three ethnic communities varied con-

siderably in the late 1940s and early 1950s, they have experienced similar trendsin recent decades and their relative shares of women in the childbearing years were

within a percentage point of each other in 1974. In particular, the sharp increasein young women from 1966 to 1974 was common to all, although the increase was

most dramatic for the Indian population..But initial differences in age-sex structure were considerable in the im-

mediate postwar years, hi 1950, the Malay age-sex structure was most favorable to

high fertility, while the Indian and Chinese population composition depressed theirbirth rates. As the Chinese and Indian populations became more "normal" in the1950s and 1960s (though not consistently for all ages), the proportionate share ofyoung Malay women actually decreased through the mid-1960s. This was not dueto a slow growth in absolute numbers (witness the percentage change figures in

right-hand panel of Table 1), but rather due to the relatively more rapid growth ofother age groups, especially for those below age 15. The result is, as will be demon-strated later, age-structure changes were a partial contributor to a reduction in theMalay crude birth rate in the 1960s, but not for the Chinese or Indian populations.But in the 1970s the age structure of all three ethnic communities will act to

increase the birth rate.

Changes in Marital Structure, 1947-1970

There have been two secular trends in marital patterns in Malaysia duringthe postwar era. The dominant one has been a trend toward a later age at first mar-riage, most evident in the 1960s. The other trend, an increase in the proportion cur-

rently married above age 30, is a result of a decline in widowhood and divorce.Both these patterns are evident in Table 2 which shows the proportions of womencurrently married and ever married by five-year age groups from the 1947, 1957,and 1970 censuses.

The rise in age at first marriage is most evident in the proportions ever-married. Almost 60 percent of Malay women age 15-19 were ever-married in 1947,this figure dropped modestly to 54 percent in 1957, but sharply to 22 percent in1970. The 1957-1970 decline in the percent of women 20-24 ever-married is alsoquite startling, 91 to 68 percent. Above age 25 over 90 percent of Malay womenwere ever-married in 1970; thus, marriage may be delayed, but it still appears to

be a universal norm. The trends toward higher proportions "currently married"in the older age groups among Malay women is also striking, though to a muchsmaller degree. These include rises in age groups 20-24, 25-29, 30-34 from 1947to 1957 and for all age groups 30-34 and above from 1957 to 1970.

100

TABLE 2

Proportion of Women Currently Married and Ever-Married by Age Croup andEthnic Community: Peninsular Malaysia, 1947-1970

Total15-1920-2425-2930-3435-3940-4,4

45-49

15-49

Malay15-1920-2425-2930-3435-3940-4445-49

15-49

Chinese15-1920-2425-2930-3435-3940-4445-49

15-19

Indian15-1920.2425-2930-3435-3940-4445.49

1549

C1947

37.678.787.787.187.475.567.7

73.4

50.781.586.785.489-673.065.1

76.1

17.271.688.389.586.880.072.7

68.7

50.788.891.687.379.767.856.5

76.7

currently marrie1957

34.774.889.790.987.780.7715

72.4

50.084.390.889.885.877.567.7

77.1

10.256.286.892.490.384.676.5

63.1

52.188.494.493.389.079.466.9

80.2

d1970

15.355.083.089.889.785.980.0

62.4

21.564.286.490.689.485.179.0

66.5

5.839.977.488.289.887.482.1

56.0

16.661.685.791.590.385.778.9

62.9

1947

42.286.796.197.696.597.897.5

84.7

59.293.497.998.795.998.998.6

89.8

17.673.992.195.896.796.496.3

76.3

52.393.198.298.899.098.698.4

89.2

Ever-marrii1957

37.078.694.497.998.598.598.6

80.6

54.190.697.698.899.299.499.4

87.6

10.356.888.696.297.397.497.5

68.3

53.290.697.598.999.599.599.4

88.1

sd1970

16.157.086.294.496.798.198.7

67.5

22.767.691.396.798.198.999.3

73.1

6.040.378.690.594.396.697.6

59.0

17.063.088.396.197.998.699.0

67.7

Sources: Malaya (1949), pp. 204-259. Department of Statistics, Federation of Malaya (1960),pp. 72-76. Department of Statistics, Malaysia (1977) Volume 2, pp. 355-359.

101

Marital disruption due to divorce has been a very common pattern amongMalays (see Djamour, 1965), but these data suggest the frequency of divorce mayhave declined over the years (3). Palmore and Ariffin (1969) note that the time

spent out of marital unions due to divorce (remarriage is very common) effectivelyreduces Malay fertility. Thus a trend towards more stable marriages may increase

the potential of a rise in fertility among middle-age women.A pattern of later age at marriage has been common among Chinese in

Malaysia and elsewhere. Even in 1947 only 18 percent of Chinese women age 15-19 have ever been married, although this figure rose to 74 percent in the 20-24

age category. But a strong secular trend toward delayed marriage has reduced these

figures to 6 percent and 39 percent respectively, by 1970. There are even signs ofdelayed marriage among women in their late twenties with only 79 percent of Chi-

nese women age 25-29 ever married in 1970. There is relatively less of the othertrend in the increase of "currently married" at older ages among Chinese than was

evident in the Malay population. There are some shifts in this direction from1947 to 1957, but none from 1957 to 1970.

The marriage patterns among the Indian population resemble those of theMalay population with very high proportions of young women married in 1947,but very sharp subsequent declines,’especially from 1957 to 1970. In fact, the de-

clines for young Indian women have been greater than for the Malay women.

The rises in the proportion "currently married" of older women is also’evident in

the Indian population above age 25 from 1947 to 1957, and above age 35 from1957 to 1970. We suspect that this may be the result of a modest decline in

widowhood.The figures for the total population are a weighted average of the marital

patterns of the three ethnic communities. Because the overall trends are similarin all three ethnic communities, there are no real surprises here. Clearly, the verygreat decreases’ in the proportions married at the younger .ages in the last two de-cades can be considered a minor social revolution, which deserves more detailed

scrutiny.

THE PEMOD OF HIGH FERTILITY AND INCIPIENT DECLINE, 1947-1958

A detailed review of Malaysian fertility trends and differentials can beseparated into two periods 1) the pre-decline period from 1947-1958, and 2) the

period of rapid fertility decline from 1958 to 1974. Not only are the prevailingpatterns quite different in these two eras, but the scope of the analysis can be

(3) Variations in cross-sectional differences in marital status also reflect differencesin the extent and timing of remarriage. A detailed analysis of these patterns is not possible withthe available data.

TABLE 3

Trends in the Crude Birth Rate, General Fertility Rate, and the Standardized Crude Birth Rate by Ethnic CommunityPeninsular Malaysia 1947-1958

19471948

19491950

19511952

19531954195519561957

1958

1

CBR

43.140.4

43.5

41.843.344.3

43.944.1

43.4

46.045.442.7

’otal popi

GFR

188

179196191

201207

205205

201

211

207

196

illation

Std.CBR*

41.3

39.543.4

42.444.5

46.045.245.1

44.0

46.345.3

42.7

CBR

41.6

37.143.3

42.1

44.9

46.345.446.645.3

49.347.8

45.5

Malay

GFR

169151

176172

184

189187

193

189208

203

196

Std. CBR*

35.932.4

38.137.3

40.041.4

40.741.9

40.9

44.643.4

41.9

CBR

44.344.2

43.341.641.5

42.2

41.941.0

40.8

41.5

42.1

38.6

Chinese

GFR

208206

202

194195

199198

194194

199203185

Std. CBR*

48.448.0

47.045.2

45.4

45.3

45.7

44.644.3

45.2

46.041.7

CBR

49.144.2

47.843.7

44.7

45.446.5

46.546.4

48.7

48.645.3

Indian

GFR

236212230

211

217222

229

232

234

250254

239

Std. CBR*

49.745.4

49.946.247.8

49.350.650.951.2

54.2

54.7

51.2

Indirectly standardized on the 1958 total population age-specific birth rates.

Sources: 1) Births from the Federation of Malaya (1948-1959) Report of the Registrar-General on Population, Births and Deaths, various issues.For complete listing, see Hirschman (1978), Appendix tables.2) Population estimates from adjusted 1947 and 1957 census data and intercensal interpolations, see Hirschman (1978), Appendix tables.

103

considerably enlarged for the second period because births from the vital registra-tion system have only been tabulated by age of mother from 1958 onwards (firstpublished from 1958 onwards in the Department of Statistics, Vital Statistics:States of Malaya, 1964.). .Our analysis of period fertility trends will be separatedinto the pre-decline and post-decline era. A subsequent section will consider theentire postwar era using cumulative fertility measures based upon the children-ever bom data from the 1947, 1957, and 1970 censuses.

Table 3 presents annual fertility rates from 1947 to 1958 using the onlycalculable period rates based upon vital statistics data: 1) the crude birth rate,2) the general fertility-rate, and 3) the standardized crude birth rate. Because thecrude birth rate is partially a reflection of the age-sex composition of a population,the Malay population, which had a somewhat higher proportion of women in thereproductive years than either the Chinese or Indian populations during this period,has relatively higher crude rates than the more refined measures indicate. Thestandardized crude birth rates were indirectly calculated on the 1958 age-specificfertility rates of the total population (Shryock, Siegel and Stockwell, 1976:285).The standardization procedure allows for comparisons between ethnic communitiesand over time by eliminating variations due to differences in age structure.

Ethnic Differentials in the Early Postwar Years

Crude rates show that the Malay, Chinese and Indian communities havesimilar fertility levels in the late 1940s and 1950s with rates in the low to mid40s. While the Indian crude birth rate seems to be somewhat higher and the Chineseis the lowest in most years, the differences are too small and inconsistent to beworth a substantive interpretation. But a close reading of the more refined generalfertility rates and the standardized crude birth rates (standardized on the 1958Total Population age-specific fertility rates) show quite a different picture.

According to these figures which modify the fertility depressing age-sexstructure of the Chinese and Indian populations, Malay fertility is considerablybelow that of the other two communities. The extraordinarily high fertility of theIndian community is particularly striking with general fertility rates in the 220-250range and a standardized crude rate hovering around 50.

While part of the ethnic differential in fertility may reflect greater under-registration of Malay births, other researchers have also found lower Malay fertilityusing census cumulative fertility measures and adjusted vital statistics data (Smith,1952; Saw, 1967b). There are plausible reasons for believing that the relatively lowMalay fertility indicators may be true (though they are undoubtedly depressed byincomplete registration in the late 1940s), in spite of the fact that they were themost rural and agrarian ethnic community, and the conventional expectation isthat traditional village Hfe encourages very high fertility levels. First, the highermarital disruption rates (and mortality) in the Malay community probably reduced

104

the average length of married life .exposed to the risk of childbirth (Palmore andAriffin, 1969). Additionally, low levels of nutrition may have reduced fecundity,and consequently fertility. Finally, we know that many traditional populations,both pre-industrial and contemporary, limit their fertility through a variety ofinstitutional mechanisms (Wrigley, 1969, Kumar, 1971). While we have ho directevidence that Malay fertility was consciously (or unconsciously) regulated, thehypothesis is an entirely plausible one.

Trends, 1947-1958

Previous research which compared 1947 and 1957 Malaysian fertility levelshas concluded that fertility had risen over this period (Saw, 1967a, 1967b; Palmore,et al., 1975). The annual data in Table 3 tend to support this interpretation for theMalay and Indian population (and indirectly for the total population), while thetrend for the Chinese community is less consistent. To the extent that coverageof births in the vital registration system became more complete over the years, thiswould also tend to push the "reported" fertility rates upward. But even using"adjusted" birth rates, Saw (1967a, 1967b) reports a rise in fertility from 1947to 1957.

It seems likely that fertility should have risen in the immediate postwaryears. The period of the Japanese occupation (1942 to 1945) was one of economicdisruption and hardship that probably increased infant mortality and also led tosome postponement of marriages and births (there is no definitive social historyof the Japanese occupation, but some accounts can be found in Purcell, 1967,pp. 243-262, and Gullick, 1969, pp. 94-98). From the incomplete vital registrationrecords that remained, the Registrar-General of Births and Deaths in 1946 puttogether the following estimates on the numbers of births:

1940194119421943194419451946

186,028142,339151,181176,669153,198103,747183,960

Source: Malayan Union. 1948 Report on the Registration of Births and Deaths forthe Years 1941 to 1946 p. 2;

In 1947, the number of annual births rose above 200,000 and it has beenabove this figure in all subsequent years.’ Thus, an immediate rise in the late 1940sseems certain, but beyond that, the pattern is erratic, without a consistent year toyear trend.

105

In addition to variations caused by improvements in the completeness ofcoverage, there were a couple of major political-economic events that may havehad an impact.on fertility- (and vital registration) during these years. The first wasthe outbreak of the "Malayan Emergency" in 1948 (Short, 1964; Gwee, 1966).Basically this was a war waged by a relatively small number of indigenous guerillaforces, primarily Chinese, against the colonial government. Although the battleswere mostly jungle skirmishes and ambushes, the civilian population was notentirely isolated. The colonial government’s resettlement program in the early1950s moved hundreds of thousands of rural residents, largely Chinese, into "newvillages" that became small towns or were adjacent to larger towns (Sandhu, 1964).Such events might have served to reduce, or at least interrupt, fertility, especiallyamong the Chinese. The other major event was the Korean War boom in rubberprices that led to a tremendous wave of relative prosperity in 1950 and 1951.Rubber prices quadrupled from 1949 to 1951 (Stubbs, 1974:10), and the effectswere felt by many small rubber growers in rural villages. A temporary increase in

.affluence without any accompanying socio-structural change might have increasedfertility (by improving nutrition, lowering age at marriage, or raising maritalfertility).

The Malay community had the most clear-cut trend towards rising fertilityduring this period with modest upturns in 1951 and 1956 (in all measures) thatwere maintained in spite of year to year fluctuations. How much of this rise wasdue to improved registration of births and not "real" increases in fertility is impos-sible to measure, but we suspect a large fraction is real.

Among Chinese, there was a very modest fertility decline of five percentor so from the late 1940s to the early 1950s and then no change after that. Notuntil 1958 do we begin to see the incipient decline in fertility evident in theChinese rates. By this time, Chinese and Malay fertility appear to be fairly equiva-lent in the general fertility and standardized crude birth rates. But as will be shownshortly, the more refined total fertility rate still had Chinese fertility above theMalay level in 1958.

As noted earlier, Indian fertility was considerably above Malay andChinese levels. After some oscillations in the late 1940s, Indian fertility seems tohave risen slowly through the early and middle 1950s, reaching a peak in 1947 witha general fertility rate above 250 meaning that one quarter of women in thereproductive ages (15-49) had a baby in that year. This figure was 25 percent aboveMalay and Chinese levels in that year.

But 1958 was the turning point, which saw fertility begin to decline inall three communities. Fortunately, births by age of mother are available for 1958and subsequent years, making possible. a more detailed analysis of the fertilitydecline in the 1960s and 1970s.

106

THE PERIOD OF RAPID FERTILITY DECLINE, 1958-1974

In comparative :historical perspective, the downward path of fertilityfrom the late 1950s to the early 1970s has been very rapid. Both crude and refinedfertility measures show a drop of more than 25 percent from 1958 to 1974. By1974, the crude birth rate was slightly above 30 and the total fertility rate was 4.3children per woman. If this decline continues at the same pace, fertility wouldreach the contemporary levels of Western countries in the 1990s. The declines to

date are not an artifact of changes in age structure, in fact, population compositionhas become more favorable to a higher birth rate in recent years. Both the rising ageat marriage and declines in marital fertility have been important factors accountingfor the decline in period rates (4). These patterns are revealed in Table 4 whichshows the changes in summary fertility measures as well as age-specific rates for the1958-1974 period for the total population and separately for Malays, Chinese, andIndians. Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 show the annual time-series in age-specific fertilityrates for the same period for each of the four populations (Total Population,Malays, Chinese, and Indians). To order the discussion of these patterns, we willbegin with changes in the fertility patterns of the total population and then turn toa comparison of the three ethnic communities and their somewhat different pathsof fertility decline.

For the total population, there is relatively little difference in the percen-tage declines in the various summary fertility rates from 1958 to 1974 (28 percentdecline in the crude birth rate and 30 percent in the total fertility rate). The crudebirth rate declined slightly faster than the total fertility rate in the late 1950s andthrough the mid 1960s, but the reverse was true in the early 1970s. While age-sexstructure was becoming more unfavorable to fertility earlier in the period, it is nowpushing the crude rate higher as the large postwar cohorts enter their childbearingcareers. The decline of almost two children per woman in the total fertility rate

(6.187 to 4.345) over 16 years is rather amazing. As we shall see later, this figureis an average of much greater declines among the Chinese and Indian populationsand a lesser drop in the Malay community. Looking at the age-specific rates, thereare sizeable declines in all age groups, though the greatest have been among youngwomen, below age 25. The time-path of different age groups is most clearly shownin Figure 2. Declines were evident from the beginning of the period for those age15-19 and 20-24, clearly a sign of the rising age at marriage. For women in themiddle age groups 25-29 and 30-34, the first consistent signs of the downwardmovement are ^evident in the.late 1960s. The trends for women above 35 are more

flat, though there are reductions evident here also.

(4) This interpretation was clear in the late 1960s, see Cho etaL, 1968. It is furtherdocumented in Retherford and Cho. 1973 and later in this paper.

FIGURE 3 TRENDS IN RGE SPECIFIC FERTILITY RRTES OF THEMRLRY POPULRTION: PENINSULRR MRLRYSIR, 1958 197t

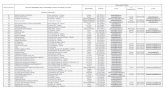

TABLE 4

Trend in Crude and Refined Fertility Rates by Ethnic Community: Peninsular Malaysia, 1958-1974

Crude birth rateGeneral fertility rateTotal fertility rate

Age-specific fertility rates

15-1920-2425-2930-3435-3940-444549

MALAYCrude birth rateGeneral fertility rateTotal fertilityTate

Age-specific fertsStyrcrtet15-1920.2425-2930-3435-3940-4445-49

1958

42.7196

6187

1263143132391596619

45.5196

5882

1733332772021314316

1962

40.1189

5992

104297315255156657

42.0189

5806

149308291

2226133486

Fertility ra

1966

37.21735713

782583062521636718

39.9180

5877

1042832972441636520

tea

1970

32.5146

4885

552262662191403616

34.21525090

722432572221485719

1974

TOTAL30.9132

4345

47197240201130469

33.4143

4752

602182422091555312

1958-1962

POPULATION-6.1-3.6-3.2

-17.5-5.4

0.66.7

-1.9-1.5-63.2

-7.7-3.6-1.3

-13.9-7.5

5.111.91.5

11.6-62.5

1962-1966

-13.-8.5-4.7

-25.0-13.1-2.9-1.2

4.53.1

157.1

-5.0-4.8

1.2

-30.2-8.1

2.18.0

22.635.4

233.3

Percenti1966-1970

-12.6-15.6-14.5

-29.5-12.4-13.1-13.1-14.1-16.4-11.1

-14.3-15.6-13.4

-30.8-14.1-13.5-9.0-9.2-12.3-5.0

change1970-1974

-4.9-9.6-11.1

-14.5-12.8-9.8-8.2-7.1

-17.9-43.7

-2.3-5.9-6.6

-16.7-10.3-5.8-5.9

4.7-7.0-36.8

1958-1974

-27.6-32.7-29.8

-62.7-37.3-23.3-15.9-18.2-30.3-52.6

-26.6-27.0-19.2

-65.3-34.5-12.6

3518.323.3

-25.0

CHINESECrude birth rate 38.6 37.0 33.5 30.5 27.7 -4.1 -9.5 -9.0 -9.2 -28.2

General fertility rate 185 179 157 136 116 -3.2 -12.3 -13.4 -14.7 -37.3

Total fertility rate 6546 6145 5390 4624 3838 -6.1 -12.2 -14.2 -17.0 -41.4

Age-specific fertility rates

15-19 42 33 32 25 25 -21.4 -3.0 -21.9 0.0 -405

20-24 261 251 210 190 158 -3.8 -16.3 -9.5 -16.8 -39.5

25-29 359 339 312 280 236 -5.6 -8.0 -10.3 -15.7 -34.3

30-34 304 299 262 222 196 -1.6 -12.4 -15.3 -11.7 -35.5

35.39 214 199 168 136 104 -7.0 -15.6 -19.0 -23.5 -51.4

4044 105 99 75 59 41 -5.7 -24.2 -21.3 -30.5 -61.045-49 25 9 18 13 6 -64.0 100.0 -27.8 -53.8 -76.0

INDIANCrude birth rate 45.3 42.0 37.8 31.8 29.8 -7.3 -10.0 -15.9 -6.3 -34.2

General fertility rate 239 232 197 152 130 -2.9 -15.1 -22.8 -14.5 -45.6Total fertility rate 7216 7122 6414 4960 4131 -1.3 -9.9 -22.7 -16.7 -42.8

Age-specific fertility rates

15-19 222 167 123 71 52 -24.8 -26.3 -42.3 -26.8 -76.620-24 398 415 325 279 225 4.3 -21.7 -14.2 -19.4 -43.525.29 359 362 339 262 248 0.8 -6.4 -22.7 -5.3 -30.930-34 257 274 270 205 178 6.6 -1.5 -24.1 -13.2 -30.735-39 149 157 156 119 92 5.4 -0.6 -23.7 -22.7 -38.3

4044 46 46 56 45 26 0.0 21.7 -19.6 -42.2 -43.545-19 13 4 14 10 5 -69.2 250.0 -28.6 -100.0 -61.5

Source*; 1) Births from Department of Statistics (1964-1976) Vital Statistics, Peninsular Malaysia, various issues. For complete listing, see Hirechman

(1978) Appendix tables.2) Population estimates from adjusted 1957 and 1970 Population Census data, intercensal interpolations, and post censal estimates (after1970), see Hiradunan (1978) Appendix tables.

FIGURE t TRENDS IN RGE SPECIFIC FERTILITY RRTES OF THECHINESE POPULRTION: PENINSULRR MRLRYSIR, 1958 197t

FIGURE 5 TRENDS IN RGE SPECIFIC FERTILITY RRTES OF THEINDIRN POPULRTION: PENINSULRR MRLRYSIR, 1958 197t

Ill

Ethnic DifferentialsAs noted previously, ethnic differentials in fertility vary considerably

depending.upon the rate used. This is shown most clearly in the 1958 columns ofTable 5. Looking at crude birth rates,. Malays and Indians appear to have about thesame fertility (45.5 and 45.3, respectively) while .Chinese are somewhat lower

(38.6). But comparing total fertility rates, Indians have very high fertility (7.216)with Chinese about .7 of a child per woman lower (6.546) and Malays averagingover .6 of a child less per woman (5.882) than the Chinese. Obviously the unfavor-able age-eex composition of the Chinese and Indian populations depressed theircrude rates. A comparison of the age patterns of fertility shows that the Chinesehave a much later fertility schedule than do either Malays or Indians. The Indian

age-specific rates are extraordinarily high, especially at the younger ages about 4out of every 10 Indian women in their twenties had a baby in 1958. While Malayfertility was quite high at the younger ages (though below that of Indian women),it was quite low for women above age 30. A somewhat higher proportion of olderMalay women are not "currently married" due to higher incidence of divorce (seeTable 2) but even marital fertility rates of Malay women above 30 are belowChinese and Indian levels in the late 1950s. This finding corroborates Palmore andAriffin’s (1969) analysis of differential marriage patterns and fertility in Malaysia.They found that multiple marriages (married twice or more) lowered cumulativeMalay fertility. Even among women married only once (and controlling for age at

marriage), Malay cumulative fertility in 1966 was below that of Indian and Chinesewomen (Palmore and Ariffin, 1969:394).

But the process of the fertility declines in the 1960s reversed the patterns

of differential fertility of 1958. The pace of decline was much greater among theChinese and Indians and by 1974, Malay fertility was the highest on all measures.These patterns of change can be clearly observed in the age-specific changes in

Figures 3, 4, and 5.

Trends, 1958-1974

The Malay total fertility rate showed only minor changes until the late1960s. There were reductions in fertility among younger women (especially belowage 20) in the early 1960s, but this was almost entirely cancelled out by increases

in the age-specific fertility of women in their late 20s and 30s. The declines amongthe younger women reflect several demographic and structural changes. Rising ageat marriage (Table 2) means fewer younger women were in marital unions in thelate 1960s compared to the 1950s. This decline in proportions married occurredas the larger birth cohorts of the late 1940s and early 1950s were entering the mar-

riageable ages in the late 1960s. Relative to potential husbands who would be severalyears older (and thus bom in the late 1930s or early 1940s) there was a surplusof eligible women (this marriage squeeze was anticipated by Caldwell, 1963).

112

Additionally, the expansion of educational opportunities after Independence in1957 meant that. more women were probably postponing marriage to completesecondary schooling. While these conjectures must await more empirical investiga-tion, they are consistent with the continued downward path of age-specific fertilityamong young Malay women in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The rise in age-specific fertility among older Malay women in the earlyand mid 1960s is more of a mystery (these rates began to turn downward in thelate 1960s, see Figure 3). It could possibly be a bias caused by changing com-

pleteness of coverage, although it seems unlikely that such errors should varyby age of mother. If may be that we are actually seeing’differences in completedcohort parity that are revealed in the differential trends, that is, women in theirlate 20s and 30s during the 1960s represent the cohorts of Malay women bom inthe 1930s and early 1940s whose completed family size may represent a "peak"relative to older cohorts as well as to those who follow. But since the age-specificfertility rates were relatively low in the late 1950s and the rises are fairly modestand only temporary, a number of minor factors could be responsible. But clearly a

major reduction of Malay fertility has been under way in the last decade. The totalfertility rate dropped by 20 percent to 4.7 children per woman in 1974. Althoughmost of the reduction was among younger women (below age 25), by the late1960s there were definite signs of reduced fertility among middle age women as

well.In spite of an age structure that was becoming more favorable to fertility,

the Chinese crude birth rate dropped 28 percent from 1958 to 1974 reaching a lowlevel of 27.7 in 1974. The total fertility rate dropped even more, by 41 percent oralmost two births per mother to a level of 3.8 per woman in 1974.

As the trends in Figure 4 show, significant declines were registered for allage-groups, especially for women in the middle ages, where age patterns of fertilitywere the highest among the Chinese community. These results suggest that Chinesecouples are beginning to restrict fertility within marriages after reaching their de-sired number of children. Even though fertility was already quite low for youngerChinese women due to delayed marriage, there were further reductions for womenbelow age 25 throughout the 1960s and early 1970s.

The declines in Indian. fertility levels are the most amazing of all. Fromthe very high level of 7.216 in 1958, the total fertility rate was reduced to 4.131in 1974, a decline of more than three births per woman. The reductions have beenthe greatest at the youngest ages (the ASFR of women 15-19 declined by almost80 percent), but are significant for all age groups. There were only small reductionsat theyoungest ages (15-19 and 20-24) in the first few years of the period, but fromthe late 1960s onward, .the rate of decline has. been very precipitous; from 1966-1970, the total fertility rate dropped by 1.5 births per woman and the crude birthrate by over 7 points. It may not be entirely coincidental that the largest changesin the age structure (share of young women relative to the total population, seeTable 1) were also in the Indian community.

113

Decomposition.of Changes in Crude Birth Rates, 1958-1970

To explain the decline, of fertility- over time, it is necessary to look at

associated changes in education and employment characteristics of women as wellas general secular trends in the economy and society. As a first step in the analysisof fertility change, it is possible to decompose changes in the crude birth rates over

time into three demographic components: 1) age-sex composition, 2) the propor-tion of women in the childbearing age range who have been ever-married, and 3)marital age-specific fertility’ rates. While trends in each of these components havebeen examined separately in this paper, the present objective is to measure theirrelative impact on changes in the. crude birth rate from 1958 to 1970. The compa-rison is limited to this interval because a lack of annual data on "proportion ofwomen ever-married" by age group. Such information is only available in thecensuses of 1947, 1957, and 1970. Because age-specific fertility rates are onlyavailable from 1958 onwards, I.have assumed that the marital proportions fromthe 1957 census are equal (or very close) to those in 1958. Marital age-specific rates

are computed by simply dividing age-specific fertility rates by the proportioncurrently married. The decomposition procedure is that outlined by Retherfordand Cho (1973) which is an adaptation ofKitagawa’s (1955) method. It is differentfrom that used in other fertility analyses (Freedman, et al. 1972) in that the interac-

tion term (residual) is divided among the components. (For other perspectives on

decomposition methods, see Althauser and Wigler, 1972; and Das Gupta, 1978).Table 5 presents the results of the decomposition procedure which

separates out the contribution of changes in 1) age-sex composition, 2) proportionsever-married, and 3) marital age-specific fertility rates, to changes in the crude birthrates from 1958 to 1970. The results are reported separately for the total popula-tion and the three main ethnic communities and for each age group within eachpopulation. The contributions are expressed in terms of the points of the crudebirth rate; if the number is negative it means that it contributed to the decline ofthe CBR, if positive then it acted to push the CBR upward. Thus, changes in theproportion of 15-19 year old women from 1958 to 1970 acted to push the CBR upby 0.8 points. Effects are summed across rows for each group, and down columns

for each factor. The grand sum of all contributions is the total change in the crudebirth rate from 1958 to 1970 (10.2 points for the total population). The sum ofeach factor for all age groups is also shown in parentheses as a percentage of thetotal change. Because some factors work in the opposite direction, the absolute sumof the percentages may be more than 100 percent. A negative percentage indicates

the relative magnitude in the opposite direction to the prevailing change.The change of over.10 points in the crude birth rate of the total popula-

tion from 1958 to 1970 was entirely due to reductions in the proportions marriedand in marital fertility with net changes in the age-sex structure having essentiallyno overall effects (although it did at various age groups). More specifically, 4/5of the reduction was due to the lower proportions of ever-manned women in 1970,

114

TABLES

Decomposition of Changes in the-Crude Birth Rate from 1958 to 1970 by AgeCroup and Ethnic Community: Peninsular Malaysia

Change in CBR Points Due to:

Agegroup

Total Population, 1958 CBR =42.7,15-1920-2425-2930-3433-39404443-49

Total

13-1920-2425-2930-3435-3940-4445-49

Total

Chinese Population, 1958 CBR 38.615-1920-2425-2930-3435-3940-4445-49

Total

Indian Population,15-1920-2425-2930-3435-3940444549

Total

Age-sexcomposition

0.80.5

-1.10.3

-0.2-0.0-0.0

0.1 (-1%)

Malay Population,OS

-0.7-2.0-0.5-0.6

0.00.0

-2.9(25%)

0.31.40.41.40.3

-0.2-0.1

3.5 (-44%)

2.91.6

-1.70.5

-0.0-0.1-0.0

3.1 (-23%)

%.Ever-’married

-3.7-3.6-0.9-0.2-0.1-0.0

0.0

8.5 (83%)

1958 CBR =45.6,-5.2-3.6-0.6-0.1-0.0-0.0-0.0

9.7 (85%)

-0.9-3.2-1.2-0.4-0.1-0.0

0.0

5.9 (74%)

1958 CBR =45.3,-7.1-4.8-0.9-02-0.1-0.0-0.0

-13.1 (96%)

MaritalASFR

1970 CBR =32.5-0.0-0.1-0.7-0.3-0.4-0.2-0.1

-1.8 (18%)

1970 CBR 34.2-0.1-0.3-0.1

.8

.5

.3

.0

1.2 (-10%)

1970 CBR 30.50.00.3

-1.3-1.8-1.7-0.9-0.2

5.7 (70%)

1970 CBR 31.80.00.1

-1.8-1.2-0.7

0.0-0.0

3.6 (27%)

Totalchange

-2.9-3.2-2.7-0.3-0.7-0.3-0.1

-10.2(100%)

-4.4-4.6-2.7

0.1-0.2

0.30.1

-11.3 (100%)

-0.6-1.5-2.1-0.9-15-1.1-0.3

8.1 (100%)

-4.2-3.1-4.4-0.8-0.8-0.1-0.0

-13.5 (100%)

Note: Columns may not add to totals because of founding error. A 0.0 cell means that therewere negative values of less than 0J.

Sources: Tables 1,2, and 4. Detailed age categories are not presented in Table 1, but are in-cluded in Hirschman, 1978.

115

especially those in the 15^19 and 20-24 year old age groups. Reductions in maritalfertility only accounted for a change of only 1.8 points in the CBR, about one fifthof the overall decline, in the CBR. These declines in marital fertility were in themiddle age range of the late 20s and early 30s. The demographic factors respon-

sible for the reduction of the CBR’ of the total population are a weighted average

of those for the three ethnic communities. The patterns for the three ethnic eroupsvaried considerably.

Only among the Malay population did changes in population compo-sition play a positive role in the reduction of the crude birth rate from 1958 to

1970. The impact was a modest one/only -3 points or 25 percent of the overallreduction, and the fact that changes in the proportion of Malay women age 15 to

19 had the opposite effect foretell that age-sex structure will act to push the CBRupward in the coming years. Most of the reduction in the CBR was accounted forby the declines in the proportions married (below age 25), while modest changes

in marital fertility worked in the opposite direction.Had marital fertility and marital proportions remained constant in the

Chinese population from 1958 to 1970, a more favorable age-sex structure wouldhave pushed up the Chinese CBR by over 3 points. But sizeable reductions in theproportion of Chinese women who were ever-married (in their twenties) and in

marital fertility of middle age women pushed the CBR down by 8 points.The population composition factor also worked to increase the CBR

among the Indian population, but major reductions in marital fertility and especial-ly in the proportion of young Indian women married reduced their CBR by over

13.5 points. The reduction of the proportion ever-married of 15-19 year olds from52 percent in 1958 (1957) to 16 percent in 1970 contributed to a decline of 7.1points in the CBR. The decline in Indian marital fertility was largely among middleage women (25-39).

Looking ahead to the future, it is apparent that changes in age-sexstructure are becoming more favorable to higher fertility. While the postponementof marriage has clearly been the dominant factor in fertility reduction in the past,there are limits to its role in the future. The decline of teenage marriages amongMalaysian women and even of early marriages of women in their early and middletwenties will probably continue, but most of this possible change has alreadyoccurred. It would be very unlikely to see an increase in the proportion of womenwho are single in their thirties. Marriage continues to be a universal and highlyvalued social norm. This leaves marital fertility as the maior mechanism for futurereductions in fertility. There are signs of a downward trend in marital fertilityamong the non-Malay populations, especially the Chinese, but relatively littleamong Malays up to 1970.. However, marital age-specific fertility rates in theMalay population were historically, lower than the ethnic communities, and changesmay be expected to occur somewhat slower.

116

COMPARISONS OF AGE^PECIFIC FERTILITY WITH OTHER ASIAN NATIONS

The dramatic reduction in Malaysian fertility in recent years is not an

isolated phenomenon; comparable changes have occurred in a number of Asiansocieties, including South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Ceylon. Whilethe same basic factors of social change may be at work in these different societalcontexts, the path of fertility reduction varies. Table 7 presents age-specific rates

for two time points for Peninsular Malaysia, Taiwan, and the Republic of Korea.The periods vary with the availability of data, but these are meant to suggest a

pre-decline level of fertility and a recent period that shows the extent of the declineto date. This is 1958 and 1974 for Peninsular Malaysia (total population), 1961 and1974 for Taiwan, and 1960 and 1970 for the Republic of Korea.

Both Taiwan and Korea had at their initial dates, an age pattern of fertilitysimilar to the Chinese community in Peninsular Malaysia. Most notable is the verylow fertility of women below age 20. But the structure of the fertility decline was

quite different in Korea and Taiwan. There were sizeable fertility reductions inall age groups in Korea including young women in their early twenties, suggestingthat a rising age at marriage has been an important element in the process. Incontrast, the relatively greater decline in Taiwan fertility has been most significantamong older women above 30. There have been only modest reductions in thefertility of young married women (Freedman, et al. 1972 note that while theproportions married of young women (age 20-24) have declined, marital fertilityhas risen). If anything, the Malaysian changes are more similar to the Koreanexperience, with only very minor changes occurring in the marital fertility of olderwomen (above 30). It is clear that the major factor in the reduction of Malaysianfertility has been the postponement of marriage and childbearing among youngwomen. Whether these postponements are only temporary or are permanentreductions that will result in lowering of completed fertility is as yet uncertain.

TABLE 6

Comparison of Recent Changes in Ase-Specific Fertility Rates inPeninsular Malaysia, Taiwan, and Korea

Age Peninsular Malaysia Taiwan_____ Republic of Korea1958 1974 1961 1974 1960 1970

15.19 126 47 45 34 36 1320-24 314 197 249 197 259 16825-29 313 240 342 235 336 27830-34 239 201 246 96 283 18935-39 159 130 157 35 212 10140-44 66 46 71 10 100 3445-49 19 9 10 2 7

TotalFertility 6187 4345 5608 3045 6130 3940Rate

unavailable

Sources: (1) Table 4; (2) Freedman, Ronald, et al. 1977; (3) Cho, Lee Jay. 1973.

117

TRENDS IN CUMULATIVE FERTILITY, 1947-1970

Our final view of the.Malaysian fertility decline is a comparison of cumula-tive fertility .from the. 1947, 1957 and 1970 censuses. Each ever-married womanwas asked her total number of live births up to the time of the censuses. The meanvalues of children ever-born by age group and ethnic community are presented in

Table 7. The top panel is computed on the basis of all women (regardless of marital

status), and the lower panel consists of mean cumulative fertility for ever-marriedwomen only (5).

Reading down columns of Table 7 shows inter-cohort differences in fertili-ty for the same date. Of course, the younger cohorts, below age 40, differ in theirexposure to childbirth and their completed fertility levels may ultimately be higher.Reading across rows shows inter-cohort differences in cumulative fertility, holdingaae (or exposure) constant. Differences in fertility between cohorts at the youngerages may reflect differences in tuning (e.g. temporary postponement) as well asthe eventual total number of births per woman. Because secular trends influencingfertility (as observed in the period rates) affect different cohorts at varying agesof their childbearing careers, and differential responses of lowered fertility andpostponement are often intertwined, it is difficult to detect recent fertility trendswith cumulative fertility measures. But let us examine the overall patterns evidentin Table 7.

As expected, mean fertility rises from the youngest age groups to higherlevels for older women. But surprisingly, average fertility declines from a peakvalue for women in their forties to lower figures among older women. Since fertilityis essentially completed for all women above age 40, these figures would suggesta modest rise in completed cohort fertility from early in the 20th century until the1950s (the cohorts with the highest fertility would be those bom in the 1920s andearly 1930s). This appears to be a plausible interpretation, and other researchers ofMalaysian fertility have noted it as well (Smith, 1952, p. 39). Given the fact thataverage fertility levels were fairly low for a pre-industrial society (about 4 or 5children per woman), increased fecundity due to improved nutrition or otherinstitutional changes could easily have resulted in rising fertility levels across

cohorts. But there are other possible explanations. Older women may be more

likely to forget births, especially those that died shortly after birth. The author ofthe 1947 Census Report suggested that many older women may report the number

(5) The author of. the 1947 Census-Report concluded that women with no childrenwere incorrectly coded as having an "unknown number of children" (see Malaya, 1949, pp. 65-67). For this reason, women with unknown fertility were included in the denominator in the1947 calculation .(but not for 1957 and 1970) of mean number of. children ever bom in theupper panel of Table 7.

Mean Cumulative Fertility of All Women and Ever-Married Women by Age and Ethnic Community: ,_,Peninsular Malaysia, 1947, 1957, and 1970.

Age at Total Population Malay Chinese Indian

census 1947* 1937 1970 1947* 1957 1970 1947* 1957 1970 1947* 1957 1970

All women

15-19 0.27 0.32 0.11 0.40 0.47 0.15 0.09 0.07 0.04 0.30 0.54 0.1420-24 1.32 1.62 1.03 1.48 1.94 1.25 1.01 0.96 0.64 1.46 2.18 1.4125-29 2.47 3.22 2.78 2.60 3.42 3.12 2.21 2.81 2.20 2.55 3.69 3.2830-34 3.37 4.32 4.31 3.53 4.34 4.65 3.18 4.30 3.67 3.32 4.62 4.9935-39 3.97 4.95 5.48 4.22 4.94 5.68 3.73 5.05 5.09 3.84 5.01 5.874044 4.12 5.10 5.98 4.41 5.07 6.06 3.81 5.26 5.89 3.95 4.91 6.064549 4.10 4.92 5.66 4.57 5.00 5.49 3.63 4.91 5.95 3.97 4.71 5.8550-54 3.85 4.62 5.40 4.35 4.85 5.30 3.23 4.41 5.69 3.76 4.51 5.0755-59 3.62 4.41 5.17 4.42 4.84 5.20 2.93 4.01 5.21 3.92 4.42 5.0060-64 3.60 4.25 4.77 4.23 4.71 4.76 2.70 3.71 4.84 3.74 4.56 4.6165and+ 3.71 4.14 4.30 4.30 4.76 4.81 2.60 3.40 3.79 3.99 4.37 4.55Total 15 and+ 2.70 3.22 3.22 2.93 3.35 3.41 2.40 3.00 2.93 2.61 3.40 3.29

Ever-married women

15-19 0.64 0.86 0.87 0.68 0.86 0.82 0.52 0.66 1.04 0.58 1.02 1.1120-24 1.52 2.06 1.92 1.59 2.15 1.92 1.37 1.69 1.76 1.57 2.41 1.2925-29 2.57 3.41 3.25 2.66 3.51 3.44 2.41 3.18 2.83 2.60 3.78 3.7630-34 3.46 4.42 4.60 3.58 4.40 4.81 3.32 4.48 4.12 3.37 4.68 52535-39 4.06 5.03 5.67 4.26 4.98 5.79 3.86 5.20 5.41 3.88 5.04 5.974044 4.22 5.18 6.10 4.48 5.10 6.11 3.96 5.41 6.10 4.01 4.94 6.144549 421 4.99 5.73 4.64 5.03 5.53 3.77 5.05 6.08 4.04 4.74 5.9450-54 3.96 4.70 5.47 4.44 4.88 5.35 3.36 4.53 5.81 3.87 454 5.0755-59 3.75 4.49 5.25 4.50 4.87 5.24 3.08 4.13 5.33 4.01 4.45 5.0560-64 3.72 4.30 4.84 4.33 4.74 4.80 2.83 3.78 4.97 3.85 4.60 4.6165and+ 3.76 4.19 4.39 4.34 4.78 4.85 2.64 3.46 3.91 3.93 4.43 4.72Total 15 and+ 3.11 3.85 4.46 3.21 3.75 4.44 3.01 4.03 4.47 2.91 3.81 4.64

* Women with number of children ever bom not reported in 1947 are assigned to the zero parity category, see Malaya (1949), pp. 65-67.

Soumes: Malaya (1949) pp. 260-285. Department of Statistics, Federation of Malaya (i960), pp. 158-162. Department of Statistics, Malaysia(1975), .02 Sample Tape.

119

of children currently alive rather, than the requested number of children ever bom

(Malaya, 1949, p. 68). Another possibility is that the older respondents in the

census represent the survivors of the: cohort of women who passed through the

childbearing years. If mortality is selective of women with large numbers of children

(it could be argued either way), the lower reported fertility among the older womenmay simply represent differential survivorship. (For a similar discussion of alterna-

tive interpretations, see Department of Statistics (1977) Volume 1, pp. 393-394).Some support for these measurement interpretations is evident in that measures of

completed fertility for the same cohort often showed slight declines between

censuses.

Looking at trends in age-constant, inter-cohort cumulative fertility (acrossrows) of young women, two distinct patterns emerge. First, from 1947 to 1957,almost all age groups for every ethnic group in both the "all women" and "ever-married women" universes showed a substantial rise in fertility. While differences

in cohort fertility (age-constant) between two censuses may reflect differentialfertility prior to the first census as well as between the censuses, the latter is almostcertainly the case for the younger age groups. These patterns lend further supportto our tentative interpretation expressed earlier about period rates, that the late

1940s and early to mid 1950s were a period of rising fertility. We suspect thatpart of the rise was due to timing factors the making up of births postponedduring World War n or in the immediate postwar years and perhaps some earlier

than usual family formation in the affluent years of the Korean War rubber boom.Young women in their twenties in 1957 averaged a half a child or more than youngwomen in 1947. Differences in completed fertility also seemed to have resultedfrom the higher fertility in the 1950s as evidenced by the older women in boththe 1957 and 1970 censuses.

The other major trend in Table 7 is the reduction in cumulative fertility

from 1957 to 1970 among younger women. Women in their late thirties and earlyforties in 1970 (who began their childbearing careers in the 1950s) appear to be

finishing their reproductive years with an average of 5 1/2 births per woman and

over 6 births per ever-married woman the highest on record.But among women in their twenties (and for Chinese women in their

thirties) in 1970, the full effect of the lowered fertility of the 1960s is evident.Because of the delayed marriage among these women, their mean fertility in 1970is about one-half a birth less than the comparable age categories in 1957. Amongthe Malay and Indian populations, most of the reductions in cumulative fertility

are due to declines in the proportions married. The patterns of mean number of

live-births per ever-married women show only very small reductions from 1957 and

1970. In fact the average fertility of teenage married women (and 20-24 of Chinese

women) is higher in 1970 than in 1957. Because of the decreasing proportion of

teenage marriages in Malaysia; those that still do get married at very young agesprobably represent a very select group with regard to higher than average fertili-

ty.

120

CONCLUSIONS

In 1947, fertility levels were high in Peninsular Malaysia with a crude birthrate of 43. But even this high level was somewhat of an understatement of fertilitylevels in the society. In addition to the expected factors of a probable underregi-stration of births that lowered the reported fertility rates and very high infantmortality rate that partially offset high reproduction, there were several other uni-

que conditions: 1) a slow economic recovery from the unsettled conditions ofWorld War II, 2) age-sex structures that were very unfavorable to fertility amongthe Chinese and Indian populations, 3) fairly low marital fertility among the Malaycommunity, the most rural and agricultural of the major ethnic communities.Under such circumstances, the forces of social change and modernization were slowto lower fertility.

Indeed it is not until the late 1950s, in 1957 and 1958, that the first signsof a continued and sustained decline in fertility began to emerge. A comparablemajor’ decline in mortality rates began in the first years of the same decade. (Itmay be that there has been a long term decline in mortality in prior decades, butthere are inadequate data to test this hypothesis). After some erratic ups and downsin fertility rates in the late 1940s, there appears to have been a modest rise inrefined period fertility rates for both Malays and Indians, though not for Chinese.Comparing children ever-born data from the 1947 and 1957 censuses, there appearto be similar rises in marital fertility for all ethnic groups (though this was partiallycancelled out by declines in the proportion of young women married in the Chinesecommunity). Assuming the rise in fertility is real in the early 1950s, what factormight explain it? First, there may have been some "making-up" of fertility thatwas postponed during the unsettled conditions of the 1940s. Additionally, the waveof general prosperity that was brought about by the temporary boom in rubberprices during the Korean War might have stimulated higher childbearing. While itis most common to think that economic progress brings about a lowering of fertili-ty, this is usually interpreted in a framework of structural changes in economic

activities, family roles, and residential locations. Since none of these changesloomed large during this period (except urbanization as a result of the governmentresettlement program), temporary affluence might have had the effect of increas-

ing marital fertility. The stability of Chinese fertility during this period, in spite ofa substantial trend in marital postponement among young women, may reflectsimilar pressures toward higher fertility. Chinese already had a much later average

age at marriage than the other.communities in 1947s and this trend continued from1947 to 1957. One possible explanation here would be the resettlement program ofthe government which shifted hundreds of thousands of rural residents into "newvillages" (Sandhu, 1964) and consequently interrupted traditional familial andsocial organization. Most of those affected by the resettlement program were

Chinese. There was also reported to be a sizeable exodus of young Chinese menduring the early 1950s who emigrated to China (Caldwell, 1963).

121

The downward path of fertility from 1958 to the present varies amongthe three ethnic communities. For Indians and especially Malays, the key factorwas the reduction of young women in marital unions, while declines in maritalfertility .were equally important among the Chinese population. But the reductions

in fertility were significant for all communities. The fall in total fertility rates

ranged from 1.2 births per woman among Malays (who had the lowest fertility at

the beginning of the decline) to 3.2 births per Indian woman from 1958 to 1974.These reductions were evident in the late 1950s, and intensified throughout the1960s and early 1970s.

Among Malays and Indians, there were signs of reductions of marital

fertility of middle-aged women (in their late twenties and thirties) beginning in

the late 1960s and 1970s. Among Malays, these modest declines followed an

unexpected rise in age-specific fertility of middle-age women in the early 1960sprobably due to a decline in marital disruption. The declines in Indian marital

fertility of older women (above age 30) has been very dramatic since 1966. Butthe key elements in the fertility declines of both Malays and Indians have beenminor social revolutions in the delay of marriage among young women. Teenagemarriage which was very common in 1957 (over half of 15-19 year olds were

married) is no longer the prevailing social custom. Only about 1 in 5 Malay andIndian women in the 15-19 age group were married in 1970 and judging from thecontinued decline in age-specific fertility of this age group through 1974, this figu-re has been reduced even further. The postponement of marriage has also reachedinto the 20-24 age group and even some modest reductions were evident in the 25-29 age group.

What social and economic factors lie behind these major demographicshifts over the past 15-20 years? It is somewhat easier to speculate about the causes

for the reductions in the marital fertility of women in their late twenties and earlythirties. With infant mortality approaching very low levels in recent years, many

couples find themselves at their desired family size midway in their reproductivecareers (the mean number of children preferred was 4.8 with 2.5 sons among Ma-laysian women age 20-39 in 1966-67, see Freedman and Coombs, 1974, pp. 13-14).As Freedman and Muller (1947, p. 4) note, this pattern of fertility decline, begin-ning among older women, was common to most Western countries. As long as

fertility ideals remain high, the pressure for reduced fertility is felt first amongthose who have reached the desired number. This pattern is evident among Chinesewomen throughout the period and among Malay and Indian women beginning in

the late 1960s,The rapid rise in average age of marriage and lowered fertility of young

women is somewhat more difficult to explain (there were even modest reductions

in marital fertility of Malay women age 20-24 from 1957 to 1970, see Table 5).While rising.education levels of women and increasing labor force participation of

youne unmarried women seem evident on an impressionistic basis, there are few

122

detailed studies on the relationship of these characteristics to marriage patternsand trends (For an analysis of social background and age at first marriage basedupon a cross-eectional sample of currently married women, see Palmore and Ariffin,1969). I would suggest one important issue (out of the many factors) in the in-creasing postponement of marriage among young Malaysians is lack of economicopportunities to begin family life; Open unemployment was measured at 20 percentamong youth (15-19) in the labor force in 1967-68 (Department of Statistics, 1970,p. 109) and this is largely an urban phenomenon. But underemployment in ruralareas and the general difficulties of youth finding productive iobs are well recogniz-ed problems. Under such circumstances, it seems that postponement of marriageand the launching of family life are likely alternatives for many young men andwomen in all ethnic communities.

Looking to the future, one thing seems clear; the continued increase ofwomen in the reproductive years. This is already evident in the young age-catego-ries of 15-19 and 20-24 and will soon be noticeable at the older age groups as well.The full reproductive impact of these baby boom cohorts has been postponed byreductions of the proportions married in these younger age groups. Within the nextdecade, we shall know whether the lowered fertility of younger women was merelya temporary postponement to older ages or will result in a permanent reduction infamily size.

REFERENCES

ALTHAUSER R.P. WIGLER M. (1972), Standardization and Component Analysis, "Socio-logical Methods and Research" 1 (August): 97-135.

ARIFFIN BIN M. PALMORE J.A.(1973),^ Third.Year Progress Report on the WestMalay-lian Family Survey, in National Family Planning Board, "Proceedings of the combinedConference on Evaluation of Malaysia National Family Planning Programme and EastAsia Population Programmes". Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Family PlanningBoard.

ARLES J.P. (1971), Ethnic and. Socioeconpmic Patterns in Mahysia, "International LabourReview" 104 (December): 527.554.

CALDWELL J.C. (1963), Fertility Decline and.Female Changes of Marriage in Malaya, "Pop-ulation Studies" 17 (July): 20-32.

CHO LJ. (1970), West Malaysia: Estimating. Recent Fertility from Data on Own Children,1958-67, Working Paper No. 1. Honolulu: East-West Population Institute.

(1971), Korea: Estimating Current Fertility from the 1966 Census, "Studies in FamilyPlanning" 2/March): 74:78.

(1973), The Demographic Situation -in the Republic of Korea, Papers of the -East-West Population Institute No. 29. Honolulu: East-West Center.

123

CHO L.J. PALMORE J.A. SAUNDERS L. (1968), Recent Fertility Trends in WestMalaysia,"Demography" 5 (2): 732-744.

CHO LJ. TAN KAH JOO E. SHANTAKUMAR G. (1969), Estimates of Fertility forWest Malaysia, 7957.j; 96 7,. Research Paper I^o. 3. Kuala Lumpur: Department of

Statistics.

DAS GUPTA P. (1978), A General Method of Decomposing a Difference Between Two Rates

into Several Components, "Demography" 15 (February): 99-112.DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS, FEDERATION OF MALAYA, (1960), 7957 Population

Census of the Federation .of Malaya, Report No. 14, by H. Fell Kuala Lumpur: De-partment of Statistics.

DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS, MALAYSIA, (1970), Socioecononuc Sample Survey ofHouseholds Malaysia 1967-68, Employment and Unemployment: West Malaysia, by

N.S. Choudhry. Kuala Lumpur: Department of Statistics.

(1973), 1970 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia: Age Distributions, by

R. Chander. Kuala Lumpur; Department of Statistics.

(1977), 2970 Population Census of Malaysia: General Report, Two Volumes, by

R. Chander. Kuala Lumpur: Department of Statistics.

DJAMOUR J. (1965), Malay Kinship and Marriage in Singapore, London: The Athlone Press

(1959).FREEDMAN R. MULLER J. (1967), The Continuing Fertility Decline in Taiwan: 1965,

"Population Index" 33 (January-March): 3-17.

FREEDMAN R. HERMALDM A. SUN T.H. (1972), "Fertiiily Trends in Taiwan: 1961-

1970", "Population Index" 28 (April-June): 141-165.FREEDMAN R. COOMBS L.C. (1974), Cross-Cultural Comparisons: Data on Two Factors

in Fertility Behavior, an Occasional Paper of the Population Council. New York: Pop-ulation Council.

FREEDMAN R. COOMBS L.C. CHANG M.C. SUN T.H. (1974), Trends in Fertility,

Family Size Preferences, and Practice of Family Planning: Taiwan, 1965-1973, Studies

in Family Planning" 5 (Semptember): 270-288.FREEDMAN R. FAN R.H. WEI S.P. WEINBERGER M.B. (1977), Trends in Fertility

and in the Effects of Education on Fertility in Taiwan, 1961-74, Studies in Family

Planning 8 (January) 11-18.

GULLICKJ.M.(1969),Mohyia. London: Emest Benn Limited.

GWEE H. A. (1966), The Emergency in Malaya, Penang, Malaysia: Sinaran Brothers Limited.

HIRSCHMAN C. (1971), Evaluation of Mortality Data in the Vital Statistics of West Malaysia,

Research Paper No. 5. Kuala Lumpur: Department of Statistics.

(1974), Estimates of the Intercensal. Population 6y Sex, Community and Age-Croup:

Peninsular Malaysia, 1957 to 1970. Research Paper No. 9. Kuala Lumpur: Department

of Statistics.

(1975), Ethnic and Social Stratification in Peninsular Malaysia, Rose Monograph

Series. Washington. D.C.: American SociologicalAssociation.

(1978), Recent Population Trends in Malaysia, Unpublished manuscript. Department

of Sociology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

124

JACKSON R.M. (1961), Immigrant Labour and the Development of Malaya: 1786-1920,Kuala Lumpur Government Printer.

KITAGAWA E.A. (1955), Components of a Difference between Two Rates, "Journal of theAmerican Statistical Association" 50:1160-1194.

KUMAR J. (1971), A Comparison between Current Indian Fertility, and. Late NineteenthCentury Swedish and Finnish Fertility,"Population Studies" 25 (July): 264-282.

MALAYA (1949), A Report on the .1947 Census of Population, by M.V. Del Tufo. London:Crown Agents for the Colonies.

MAULDIN W.P. (1976), Fertility Trends: 1950-1975, "Studies in Family Planning" 7 (Septem-ber): 242-248.

PALMORE J.A. ARIFFIN B. M. (1969), Marriage Patterns and Cumulative Fertility inVest Malaysia, 1966-67, "Demography" 6 (November): 383-401.

PALMORE J.A. GRANDER R. -FERNANDEZ D.Z. (1975), The Demographic Situationin Malaysia, in John Kanter and Lee McCaffrey, (eds.), "Population and Development inSoutheast Asia". Lesington: D.C. Health.