Arqueologa siamo/pubblicazioni/Archaeologic… · • Bkv, Iin. iectora General de la United Natins...

Transcript of Arqueologa siamo/pubblicazioni/Archaeologic… · • Bkv, Iin. iectora General de la United Natins...

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacionalde Buenas Prácticas en Patrimonio Mundial:

ArqueologíaMahón, Menorca, Islas Baleares, España 9-13 de abril de 2012

Proceedings of the First International Conferenceon Best Practices in World Heritage:

ArchaeologyMahon, Minorca, Balearic Islands, Spain 9-13 April 2012

Alicia Castillo (Ed.)

Editora Complutense

Edita: Universidad Complutense de Madrid© Copyright: Universidad Complutense de MadridDiseña: Imprenta Taller Imagen, s.l.ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1Depósito Legal: SG.155/2011

Organiza

Patrocina

Colabora

ICOMOS ESPAÑAICOMOS ICAHM. INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE ON ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT

Comité organizador:

Directoras científicas:

• Alicia Castillo, Investigadora Postdoctoral - Profesora del Departamento de Prehistoria. Universi-dad Complutense de Madrid

• Mª Ángeles Querol, Catedrática del Departamento de Prehistoria. Universidad Complutense deMadrid

Secretaria científica:

• Isabel Salto-Weis. Profesora Titular del Departamento de Lingüística Aplicada. UniversidadPolitécnica de Madrid

Representantes del Instituto Menorquín de Estudios:

• Margarita Orfila Pons. Catedrática del Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología. Universidadde Granada

• Clemen García, Institut Menorquí d’Estudis

Representantes del Consell de Menorca:

• María Nieves Baíllo Vadell, Consejera de Cultura, Patrimoni i Educació del Consell Insular deMenorca

• Simón Gornés. Técnico arqueólogo. • Joana Gual Cerdó. Técnica arqueóloga

Representante del Pla de Dinamització del Producte Turístic de Menorca:

• David Vidal, gerente

3

Comité de Honor:

• Bauzá Díaz, José Ramón. Presidente del Govern de les Illes Balears• Tadeo Florit, Santiago. Presidente del Consell Insular de Menorca• Carrillo Menéndez, José. Rector de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid• Bokova, Irina. Directora General de la United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Orga-

nization (UNESCO)• Prieto de Pedro, Jesús. Director General de Bellas Artes y Bienes Culturales del Ministerio de Cultura• Ricard, Denis. Secretario General de la Organización de las Ciudades del Patrimonio Mundial

(OCPM)• Mayor Zaragoza, Federico. Ex director General de la UNESCO• Araoz, Gustavo M. Presidente del Consejo Internacional de Monumentos y Sitios (ICOMOS)• Suárez-Inclán Ducassi, Rosa María. Presidenta del Comité Español del Consejo Internacional de

Monumentos y Sitios (ICOMOS)

Comité científico:

• Albert, Marie Therese. Dr. Professor and Holder of UNESCO Chair. Brandenburg University ofTechnology, Cottbus, Germany

• Arsuaga, Juan Luís. Dr. Codirector del yacimiento de Atapuerca. Catedrático de Paleontología dela Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España

• Barceló, Juan Antonio. Dr. Profesor de Prehistoria. Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, España. • Bordoni, Luciana. Patrimonio Culturale. Italian National Agency for new technologies, energy and

the environment (ENEA- FIM), Italy• Comer, Douglas C. Dr, RPA Principal, Cultural Site Research and Management, Inc. (CSRM), Co-

president ICHAM. USA• Criado Boado, Felipe. Dr. Director del Instituto de Ciencias de Patrimonio, Incipit, CSIC, España. • Doglioni, Francesco. Dr. Architect. Professor. Università IUAV di Venezia, Italy• Fernández Cacho, Silvia. Dra. Jefa del Centro de Documentación y Estudios,

Instituto Andaluz de Patrimonio Histórico, Sevilla• Gándara, Manuel. Dr. Arqueólogo. Profesor-Investigador, Posgrado en Arqueología, ENAH/INAH,

México• Gavua, Kodzo Dr. Professor.Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, University of Ghana• Inaba, Nobuko. Director/Professor, World Heritage Studies, Graduate School of Comprehensive

Human Sciences University of Tsukuba, Japan• Lasheras, José Antonio. Dr. Director del Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira.

Ministerio de Cultura, España• Lilley, Ian. Dr. Professor FSA. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit,The University

of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia• Martinho Baptista, Antonio. Pré-Historiador de Arte. Parque arqueológico do Vale do Côa. Secre-

taria de Estado da Cultura. Portugal• Mateos, Pedro. Dr. Científico Titular CSIC. Director del Instituto Arqueológico de Mérida, España.• Mora Alonso-Muñoyerro, Susana. Dra. Profesora de la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura.

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, España

4

5

• Murillo, Juan. Dr. Arqueólogo. Director Gerencia de Urbanismo del Ayuntamiento de Córdoba,España

• Musiba, Charles. Dr. University of Denver, Colorado, USA. Co-founder of the Tanzania FieldSchool in Anthropology

• Rodríguez Alomá, Patricia. Arquitecta. Doctora en Ciencias Técnicas, Directora de Plan Maestro.Oficina del Historiador de la ciudad de La Habana, Cuba

• Santana Quintero, Mario. Dr. Rymond Lemaire Centre for Conservation, university of Leuven(Belgium)-President ICOMOS scientific committee on heritage documentation (CIPA)

• Shady Solís, Ruth. Dra. Aqueóloga. Antropóloga. Catedrática. Universidad Mayor de San Marcos(Perú). Directora del Projecte Especial Caral-Supe

• Silverman, Helaine. Dr. Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois. Director,CHAMP (Collaborative for Cultural Heritage and Museum Practices), USA

• Sivan, Renée. Museologist. Chief curator of the Tower of David Museum - Jerusalem Israel. Heritage Presentation Specialist

• Villafranca Jiménez, María del Mar. Directora del Patronato de la Alhambra y el Generalife,Granada, España

• Willems, Willem. Dr. Dean, Professor of Archaeological Heritage Management Leiden University(UL), Leiden, the Netherlands. Co-President of ICAHM

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue

Archaeology: The Brebemi Project (Italy)

Evaluación de Impacto Arqueológico vs Arqueología

de Rescate: El Proyecto Brebemi (Italia)

S. CAMPANA

University of Siena, Department of Archaeology and the History of Arts,

Lecturer in Landscape Archaeology

Head of the Landscape Archaeology and Remote Sensing Laboratory

AbstractThe work presented in this contribution forms part of the BREBEMI project, in reaction to a major motorwayconstruction development linking the towns of Brescia, Bergamo and Milan in northern Italy for a total lengthof about 120 km. For the first time in Italy a set of non-invasive procedures was used systematically in order toreduce archaeological risk in advance of motorway construction. This innovative project relied on the methodicalcollection of information from historical and geographical documentary sources, along with geomorphologicalanalysis, the examination of existing vertical air photography, the collection of new data through targeted aerialsurvey and oblique air photography, the acquisition of LiDAR data along the whole of the motorway route (160kmsq at a resolution of 4 hits per sqm) and the systematic collection for very substantial areas of geophysicaldata, both magnetic (AMP) and geoelectrical (ARP) – a total, of 438 hectares of AMP and ARP data (mesh0,5x0.5 m and 0.5x0.08 m). Test excavations were planned and carried out systematically to verify anomaliesand the Superintendency for the Region of Lombardy also initiated random trenching for a total of 5% of thesurveyed area. A GIS platform for the project was designed to manage and integrate all of the data at every stageof development (from data acquisition in the field to interpretation and field checking) as well as to demonstrateoverall patterns and to create predictive models. The objectives of the project were to reduce as far possible un-certainty about the presence of archaeological remains along the route and in particular to identify areas whichought to be protected from destruction because of the presence of either upstanding or buried archaeological re-mains.

Key Words: Rescue/salvage archeology, Preventive archeology, Archaeological impact assessment, remotesensing, large scale continuos geophysical prospection, motorway.

ResumenEl trabajo presentado en esta contribución forma parte del proyecto Brebemi, surgido como respuesta a la cons-trucción de una importante autopista de 120 km de trazado que une las ciudades de Brescia, Bergamo y Milán,en el Norte de Italia. Por primera vez en Italia se han empleado de forma sistemática un conjunto de técnicas noinvasivas para reducir el riesgo de impacto arqueológico antes de la construcción de la autopista. Este innovadorproyecto se ha basado en la recopilación sistemática de información en fuentes documentales históricas y geo-gráficas, unida al análisis geomorfológico, el estudio de las fotografías aéreas verticales disponibles, la recopi-lación de nuevos datos a través de prospección aérea y fotografía aérea vertical específica, la toma de datos deLIDAR a lo largo del trazado de la autopista (160 km2 con una resolución de 4 hits por m2) y la recolección sis-temática en amplias áreas de datos geofísicos, tanto magnéticos (AMP) como geoeléctricos (ARP) -un total de439 hectáreas de datos AMP y ARP-. Se programaron y realizaron sondeos para comprobar anomalías y la Su-perintendencia Arqueológica de la Región de Lombardía también efectuó trincheras aleatorias en un total del5% del área estudida. Se creó una plataforma SIG para gestionar e integrar todos los datos en cada fase del pro-yecto (desde la toma de datos en campo hasta la interpretación y comprobación de los sitios) así como paracomprobar patrones generales y construir modelos predictivos. El objetivo principal del proyecto era reducir lo

66 Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

67Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

S. Campana Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...

máximo posible la incertidumbre sobre la presencia de restos arqueológicos a lo largo del trazado de la autopista,y concretamente, identificar áreas que deberían ser protegidas de la destrucción debido a la presencia de restosarqueológicos, tanto visibles como enterrados. Las enseñanzas obtenidas en este proyecto son especialmenteimportantes para cualquier trabajo arqueológico realizado en enclaves Patrimonio Mundial.

Palabras clave: Arqueología de rescate, arqueología preventiva, evaluación de impacto arqueológico, prospec-ción, métodos geofísicos, autopista.

IntroductionThe Italian term Archeologia Preventiva(AP) can be translated into English as Ar-chaeological Impact Assessment (AIA). Asthe Italian law on this matter has yet to befinalized, it is still a little difficult to illus-trate the way in which AIA is applied inItaly. However, we can start from the con-sideration of the purpose behind the law anda statement of what AIA is not.

• The new law aims to develop planningprocesses to minimize unforeseen pro-blems during development and emer-gency rescue work.

• AIA is not rescue or salvage archaeo-logy (RA/SA), its goal being that of con-taining and minimizing the needs forthese responses.Rescue Archaeology consists of ar-

chaeological survey and excavation carriedout in areas threatened by urban develop-ment or, on occasions, already under cons-truction. The development may include, butis not limited to, motorway and major cons-truction works. Unlike traditional surveyand excavation work, Rescue Archaeologyis undertaken under pressure of time. It iscarried out primarily on sites that are aboutto be destroyed or, occasionally, as a protec-tive measure to preserve archaeologicalsites located beneath urban areas. The termRescue Archaeology and its practice are lar-gely restricted to Europe, North America,South America and East Asia. In Italy theterm Rescue Archaeology is virtuallysynonymous with rescue excavation, in theform of a vast number of small-scale ‘test’

excavations [1]. Currently, the relationshipbetween Rescue Archaeology and AP/AIAcan be considered as an archaeological hotpotato, a problem difficult to deal with inItaly. It represents a real cultural challengewhich might lead to new lines of thought inthe field of archaeology, conservation andheritage management. It is predicted thatmost of the funding destined for use withinarchaeology in Italy in the near future willbe devoted only to AIA. This will most likely lead to financial speculation on thepart of powerful lobbies and large investors.

If Rescue Archaeology was born with theinterest of reducing the destruction of ar-chaeology caused by urban development andland-use, AIA’s starting point is completelydifferent: it comes from the planning process.In this new perspective archaeology shouldbe considered a key point in landscape plan-ning alongside geology, hydrology, environ-mental impact and such like. It should beclear that Archeologia Preventiva and RescueArchaeology are completely different appro-aches – they are indeed entirely opposite re-actions both in theory and in practice.Essentially, Archeologia Preventiva replacesRescue Archaeology, leaving interventionsthrough rescue work as being necessary onlywhen diagnostic and predictive archaeologyhas failed, giving to rescue archaeology –rightly – the distinctiveness of ‘emergency’work.

At present, at the beginning of each pu-blic construction project in Italy which raisesany kind of public concern, such as the cons-truction of a new urban development or the

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

68

modification of existing structures, an Ar-chaeological Impact assessment, with relatedreport, is a compulsory requirement [2].Three main steps are necessary to completesuch a report.

• The collection of background data fromexisting archaeological publications, his-torical cartography, toponymy and pa-laeomorphological studies etc.

• The interpretation of vertical air photoevidence (without, unfortunately, any re-ference to oblique photography from ex-ploratory reconnaissance) and, whenpossible or useful, the collection andanalysis of LiDAR data. In some casesfurther analysis might be required for in-dividual target areas through geophysi-cal prospection or small-scale testexcavation.

• The preparation of an ‘archaeologicalrisk assessment’ map, followed by targe-ted test excavations or larger-scale exa-mination through mechanical strippingof the surface deposits.The new law gives Italian archaeology

the opportunity to start afresh with a newapproach to methodologies developed in thefield of landscape archaeology over the pastforty years.

Unfortunately, the Superintendency, thegovernment institution in charge of conser-vation of Italian heritage assets, which hasunlimited power in this field, is currently in-terpreting the law so that the emphasis isstill on rescue excavations, in the form oflarge-scale surface stripping by machinewith only small-scale excavations using es-tablished archaeological methods.

The example illustrated by this papercomes from the BREBEMI Project in nor-thern Italy, this being the acronym used todenote a motorway construction project lin-king the cities of BREscia, BErgamo andMIlan over a length of approximately100km. The project was started before thenew law came into effect. The Superinten-

dency of Lombardy, with almost unlimitedpower within the region, required the motor-way contractors to carry out ‘excavation bysurface stripping’ over the whole of the areaaffected by the motorway construction. Therequest was logistically and financially non-sensical from the point of view of the con-tractors, as it would have increased the costof the project to an unmanageable degree. Asa result, the construction company contactedthe author and his colleagues at the Univer-sity of Siena and asked them to find an alter-native approach which might subsequentlybe acceptable to the Superintendency.

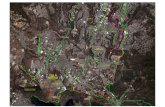

2. Landscape, research design, researchteam building and managementThe motorway is being constructed throughthe typical landscape of the Po Valley, withits extremely flat morphology and sand-and-gravel soils, heavily affected by inten-sive arable cultivation through thesystematic use of heavy-grade tractors anddeep ploughing over at least the last sixtyyears. The area also has substantial concen-trations of industrial and related residentialdevelopment (Figure 1).

For the first time in Italy the influence ofthe new law gave an opportunity to makesystematic and innovative use of a range ofnon-invasive techniques to minimise therisk of archaeological damage in advance oflarge-scale motorway construction. Theproject design therefore envisaged thesystematic collection of historical and geo-graphical data and interpretations from do-cumentary sources, along withgeomorphological studies, the analysis ofvertical historical air photographs, the initiation of new oblique aerial survey, andLiDAR acquisition along the whole of themotorway corridor, in some cases includinga substantial buffer zone on either side. Alsoincluded was the systematic collection ofgeophysical data, both magnetic and geo-electrical, across large and contiguous areas

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

69Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

of between 200 and 750 hectares respecti-vely, building on an approach successfullytested in Italy, France and above all in theUnited Kingdom [3]. Systematic test exca-vations were also planned to verify anoma-lies identified by any or all of thesetechniques. Independently, the regional Su-perintendency designed a pattern of randomtest trenches amounting to a 5% sample ofthe motorway corridor.

Within the BREBEMI company a GISenvironment was designed to manage andintegrate the collected data at all stages ofthe project, from data acquisition in the fieldto interpretation and field checking, so as toassess any significant trends in the collecteddata and to develop archaeological models.The aim of the project was to reduce the de-gree of uncertainty about the presence (orpotential presence) of archaeological re-mains by identifying areas that ought not tobe subjected to disturbance by the construc-tion works in the light of the demonstratedpresence of either surface or sub-surface ar-chaeological remains.

The Laboratory of Landscape Archaeo-logy and Remote Sensing at the Universityof Siena already had experience in usingeach of these survey methods but saw theBREBEMI project as an extraordinary op-portunity to add its weight to an importantculture-change in the theory and practice ofpreventive and rescue archaeology in Italy. Adecision was therefore taken to involve someof the most highly skilled and specializedcompanies, institutes and research workersfrom across Europe. The Laboratory usedArcheolandscapes Tech and Survey Enter-prise (ATS), a spin-off company of the Uni-versity of Siena, to act as project coordinatorand to manage the following activities:

• Aerial survey, in collaboration KlausLeidorf, of Luftbilddocumentazion fromGermany, and Chris Musson from theUK.

• Interpretation and mapping of informa-

tion from vertical aerial photographs, bythe Laboratory’s own staff.

• LiDAR processing and interpretation incollaboration with Prof Dominic Powlesland of the Landscape ResearchCentre and University of Leeds in theUK.

• Processing and interpretation of magne-tic data, again in collaboration with ProfPowlesland.

• The collection and interpretation of geo-electrical and magnetic data by SoIngs.r.l. (Italy)

• GIS and topographical survey, integratedarchaeological data interpretation, selec-tive ground truthing and test excavationby ATS s.r.l.The collection of information from his-

torical and geographical documentary sour-ces was carried out by the University ofBergamo under the direction of Prof J.Schiavini, as were place-name and geomor-phological studies.

The geophysical prospection (Figure 2)involved the use of magnetic and geoelec-trical instruments (respectively ARP andAMP, Automatic Resistivity Profiling© andAutomatic Magnetic Profiling©) developedby Geocarta, a French spin-off company ofCNRS, the National Centre for ScientificResearch. Geocarta, under the scientific di-rection of Michel Dabas, also exercisedquality control over the collected data andremained on call to provide general assis-tance throughout the whole process fromfieldwork to data processing and interpreta-tion [4]. The initial collection of the datawas undertaken by SoIng of Livorno, an of-ficial partner of Geocarta with long-stan-ding experience in geophysical survey forenvironmental projects.

Altogether, the project management in-volved the co-ordination of a team of about25 research workers from Tuscany, Nor-thern Italy, France, Germany and the UK,carrying out a wide variety of interlinked

Figure 1. General overview of the motorway path and outline of the landscape pattern (north at the top).

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

70

work in a very short period – about 4months or 80 working days (Figure 3).

3. ResultsBearing in mind the large size and peculiarshape of the survey area, this paper concen-trates for the most part on a sample area, re-presentative of the landscape as a whole interms of known archaeological data, geo-morphological complexity, the availabilityof geophysical and other survey data, andground truthing. This sample, measuringabout 20km in linear extent, lay betweenCaravaggio and Urago d’Oglio, roughlybounded by the Rivers Oglio and Serio. Theresearch work itself was divided into twomain steps: the collection of existing kno-wledge, and the survey work in the field.

• Place-name registers and historicalmaps, including historical cadastralmaps and the national maps of the Isti-tuto Geografico Militare (University ofBergamo – CST).

• The Archaeological Map of Lombardy,with related updates (University of Ber-gamo – CST).

• Maps of springs, palaeo-river channels,fluvial ridges and fluvial terraces (Uni-versity of Bergamo – CST).

• The interpretation and mapping of infor-mation from historical and contempo-rary vertical air photographs, principallythe GAI series of 1954 and the CGR se-ries of 2007 (LAP&T and the Universityof Bergamo – CST).

• New aerial prospection and air photo-graphy along the motorway route in thespring and summer of 2009 (ATS Enter-prise in collaboration with Klaus Leidorffrom Germany and Chris Musson fromthe UK).

• The capture, processing and interpreta-tion of LiDAR data (collection and in-itial processing by CGR of Parma, withfurther analysis and interpretation byATS Enterprise in collaboration withProf Dominic Powlesland in the UK).The collection and mapping of the sites

published in the Archaeological Map ofLombardy [5], with subsequent updates,produced evidence of 118 already knownarchaeological sites within the 2km widebuffer zone, representing a density of about2.38 sites per square kilometre, relativelyhigh in comparison with the national ave-rage. Even so, this obviously constitutedonly the tip of the iceberg in terms of thepotential number of sites within the survey

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

71Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Figure 2. Geophysical instruments used during the survey. Left: the Automatic Magnetic Profiler

(AMP© Geocarta), capable of recording up to 20ha each day. Right: the Automatic Resistivity Pro-

filer (ARP© Geocarta), capable of recording up to 4ha each day. To increase productivity within the

project two ARP instruments were often used simultaneously.

Figure 3. Pipeline of information and activities within the BREBEMI project.

Figure 4. Mapped evidence for part of the survey area. a) Historical cadastral map recording 3650 potentially relevant place-names and 154km of field

boundaries within the 1km-wide buffer zone on either side of the motorway corridor.

b) Distribution map of known sites and related archaeological evidence (118 in all, including 50 wi-

thin the sample area.

c) Map of springs, palaeo-channels, fluvial ridges and fluvial terraces, clearly showing the hydro-

geological volatility of the area.

d) Distribution map of features detected through exploratory aerial survey and oblique air photo-

graphy.

e) The first step involved the collection and entry into a GIS environment of all the available infor-

mation about a 2km wide buffer zone centred on the motorway corridor, from archaeological sites

and finds to geomorphology and the evidence of existing aerial photographs etc. This involved

the collection of the following information and material (Figure 4).

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

72

area. Recent studies in Tuscany, Lazio andPuglia [6] have suggested that, in the ab-sence of systematic survey projects, the ‘pu-blished’ archaeology as represented in thearchives of the Archaeological Superinten-dency, represents no more than 1% to 5%

of the ‘real’ archaeological potential. If ap-plied to the BREBEMI motorway thiswould suggest the possibility of between2000 and 12000 archaeological sites andfind-spots within the buffer zone.

The first stages of the analytical work

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

73Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

went some way towards confirming thissuspicion. For instance, the new aerial sur-vey and the analysis of the historical air-photographs added another 76 ‘sites’ ofvarious kinds, substantially enriching thelandscape picture and in some cases provi-ding very detailed information about thesites concerned. An equally important con-tribution from the air-photographic studieslay, as expected, in the reconstruction of thecenturiation grid, knowledge of which is es-sential in Italy to the better understandingof the landscape and settlement patterns ofthe Roman and later periods

In some cases, for example at a locationclose to Bariano (Figure 5), oblique aerialphotography produced really striking results,bringing to light very detailed evidence ofpost holes, graves, round barrows and otherpreviously unknown archaeological featuresbut at the same time allowing the motorwayconstruction company to take protective me-asures so as to avoid major logistical pro-blems and significant waste of money duringthe eventual construction work.

The project also involved the capture150sqkm of LiDAR data at a resolution of4 hits per square metre, covering the fulllength of the motorway corridor along withthe 1km buffer zone on either side. As notedabove, the morphology of the area is to allintents and purposes completely flat and theland use devoted for the most part to inten-sive cereal and maize production. The co-llection of LiDAR data was essentiallyaimed at identifying barely perceptible rid-ges, elevated areas and depressions, manyof them perhaps related to former watercourses. The first stage of data processing,to create a basic digital terrain model, wascarried out by CGR of Parma, the surveycompany which undertook the initial datacapture. The second step involved collabo-ration between ATS Enterprise and Prof Do-minic Powlesland in the UK, using his ownvisualization software, LidarViewer. Thisallowed the identification of 509 potentiallysignificant features, consisting of 173 de-pressions, mainly interpretable as palaeo-river channels on the basis of their size,

Figure 5. Newly discovered cropmark features near Bariano. From left to right: archaeological fea-

tures associated with ancient road systems, the centuriation pattern, large round barrows and graves.

Centre: detail of one of the cemeteries, and settlement evidence including a ditch, post holes and

probable grubenhause. Right: the relationship between the site and the planned route of the motorway.

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

74

continuity and sinuous shape, along with336 ridges or ‘elevated’ areas, at least someof them interpretable as fluvial ridges.

The collected information showed aclear tendency for known archaeological‘sites’ to occupy fluvial ridges and other‘elevated’ areas within the plain. This is notto imply that these 366 raised areas corres-pond to a similar number of archaeologicalsites, only that these areas have a higher po-tential for the recovery of traces of pasthuman activity. For instance, overlaying theLiDAR data for Bariano on the aerial sur-vey for the area shows that there is a clearcorrespondence between the features detec-ted from the air and a terrace or ridge bor-dered on either side by two shallowdepressions or ‘valleys’. An alternative in-terpretation would see the air-photo featuresas potentially continuing across the wholeof the fields concerned but only being visi-ble as cropmarks on the thinner and poten-tially drier soil of the ridges compared withthe deeper and less responsive soil in theflanking depressions.

There can be no clear rule of interpreta-tion about such situations but there aremany other instances within the survey areawhere there is a clear relationship betweentopographical features in the LiDAR dataand known or suspected archaeological sitesestablished through documentary, place-name and cartographic research or throughgeophysical prospection or air-photo stu-dies. With all due caution it is fair to stressthe importance of carefully analysedLiDAR data, even in apparently ‘unpromi-sing’ situations, in the process of archaeo-logical prospection and indeed within thearchaeological process as a whole.

Turning now to the second part of the pro-cess, and in particular the collection of ge-ophysical measurements and related groundtruthing, both the BREBEMI partnership andthe Superintendency demanded a high levelof reliability in the interpretation of the ge-

ophysical data. This is what promptedLAP&T and ATS Enterprise to involve Geo-carta in the systematic collection of ARP(magnetic) and AMP (geo-electrical) data ona field-by-field basis across the whole lengthof the motorway area. A total of 217ha ofmagnetic data and 215ha of geo-electricaldata was collected, processed and interpreted.Ground truthing of the first 150ha was ca-rried out through more than 200 test excava-tions, to a linear extent of about 5220m (2.6hectares) of ‘targeted’ interventions and a fur-ther 5000m (2.2ha) of random excavations.Before looking at the results it is worth ma-king some general comments on the kind ofhigh-speed geophysical prospection involvedin this case.

• High-speed prospection instruments de-mand high-speed processing and (moreproblematically) high-speed archaeolo-gical interpretation and mapping.

• The process of archaeological interpre-tation was more difficult in this case be-cause of the peculiar shape of the surveyarea, a strip 100-150m wide along thefull 100km length of the motorway.

• The prospection instruments for themost part performed extremely well butthe use of a prototype instrument for co-llecting the magnetic data appears tohave introduced a certain amount ofnoise into the dataset. This noise hasbeen reduced substantially in the morerecent AMP instruments.

• The background noise, along with thephysical and cultural peculiarity of thesurvey area, in particular the low mag-netic contrast and perhaps other factorsnot yet identified, resulted in the identi-fication of a large number of dipole clus-ters that were difficult to interpret,reducing the perceived reliability of thegeophysical results.Despite these problems we remain con-

vinced that the systematic high-speed co-llection of geo-electrical and magnetic data

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

75Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

is theoretically a right and proper procedurewithin such projects. In practice, however,there were too many occasions in this par-ticular physical and cultural context wherethe magnetic data did not materially help ar-chaeological interpretation.

Even allowing for these problems thegeophysical prospection enabled the identi-fication of a large range of both positive andnegative evidence for the presence or likelyabsence of buried archaeological features.A quite relevant example has been identi-fied at Antegnate, near Bergamo (Figure 6).The magnetic survey revealed several ano-malies, in particular a large number of cir-cular features or ‘ring-ditches’. The size,shape and distribution of these finds closeparallels with probably the most widespreadand numerous class of archaeological mo-nument in Europe, the ‘round barrow’. Si-milar features are found in other part of theworld too. At its most basic a round barrowconsists simply of a roughly circular or ovalmound of soil raised over a burial situatedat its centre. Beyond this there are numerousvariations which may employ, as in ourcase, a surrounding ditch. Field verificationof the features at Antegnate was extremelyinteresting. Test excavation by caterpillardid not produce any material evidence at all,whether of negative features or of pottery orbone etc. To identify the suspected featuresproperly the stripped soil had to be cleanedvery carefully by trowel. Only when thiswas done were the archaeological featuresrevealed, as illustrated in Figure 6. On thebasis of this example mechanized strippingon its own, without this careful extra work,can be expected to be extremely selectiveand inefficient in its detection of certaintypes of evidence, such as the indistinct tra-ces of ditches, post holes and pits etc.

Despite the problems encountered itshould be emphasised that the interpretationof the geophysical data in most cases achie-ved a higher level of interpretative reliabi-

lity when combined with information fromother datasets such as those derived fromdocumentary sources, cartographical stu-dies, aerial photography and LiDAR pros-pection. In the most favourable cases it isundoubtedly possible to achieve a full anddetailed interpretation of the survey data.Despite degrees of uncertainty in other ins-tances it is certainly possible to construct areasonably reliable map of archaeologicalrisk and potential which can then be subjec-ted to ground-truthing by properly conduc-ted test excavation or more substantialstratigraphical investigation in advance ofthe construction of the motorway.

4. Conclusions from the BREBEMI casehistoryOver a period of no more than 4 months ofmulti-faceted investigation it proved possi-ble to collect and interpret a vast amount ofdata, greatly enriching archaeological un-derstanding of this particular stretch oflandscape. The collected evidence and itsinterpretation also helped the motorwaycontractor to plan in advance for archaeolo-gical work which might otherwise have ne-cessitated delays and extra expenditureduring the construction work through thediscovery of unforeseen archaeological sitesand deposits.

The first 438ha of geophysical prospec-tion and ground-truthing showed up somecritical comparisons with the ‘caterpillar’prospection system adopted by the regionalSuperintendency. In this context it is impor-tant to stress that while geophysical prospec-tion and interpretation improve in reliabilityevery year it is not possible to say the samefor the method of rescue investigation adop-ted by the Superintendency, using mechani-cal stripping rather than prior survey andtargeted stratigraphical excavation. Anotherkey point is that it is not possible to verifythe results of the excavation work initiatedby the Superintendency – every archaeolo-

Figure 6. Extracts from the magnetic map represented with values ±15 nt, with related interpretation

and ground-truthing by excavation (north at the top). Top left: circular features with numerous para-

llels throughout Europe as (mainly Bronze Age) round barrows, with ground-truthing confirming

this interpretation.

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

76

gist knows that excavation destroys the evi-dence upon which it relies, especially if it isnot carried out within a suitable methodolo-gical framework. By contrast it is entirelypossible – and desirable – to use stratigraphi-cal excavation to verify and interpret poten-tial archaeological features recorded initiallythrough geophysical or other forms of non-invasive prospection.

There is a clear contrast here betweenthe approach of LAP&T and ATS Enterprisewithin the BREBEMI project compared

with the traditional approach advocated bythe regional Superintendency. Fortunatelyan ‘outside’ assessment of the relative me-rits of the two approaches, based on depo-sitions in writing and in person by bothparties, was made by the Technical andScientific Committee for Italian Archaeo-logy, consisting of leading academics alongwith the General Director of the Superinten-dency at national level. After a detailedanalysis of the two approaches the Commit-tee was unanimous in its conclusion that the

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

77Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

strategy proposed by LAP&T and ATS, andthe survey and ground-truthing work subse-quently undertaken, represented the mostadvanced approach to this kind of preven-tive and rescue archaeology so far attemp-ted in Italy and that this case study shouldrepresent a model for future projects of in-frastructure and building development.

One final observation is perhaps in order.The greatest improvement in rescue and pre-ventive archaeology will surely come notfrom technological development alone butfrom a more consistent application of the kindof ‘total archaeology’ and ‘global’ historicalapproach advocated at the beginning of thispaper. This change of approach is imperativebecause we need first to understand the localcontext by working closely with local ar-chaeologists and historians in the attempt toimprove our capacity to interpret and test the‘global’ dataset assembled from multiple sur-vey techniques. Only then will it be possibleto reduce the archaeological risk and maxi-mize the archaeological returns from preven-tive and rescue archaeology.

5. Final remarks on the relationship bet-ween Ra and AIAIn the basis of our experience in the BRE-BEMI project it is clear that rescue archaeo-logy of the kind preferred (and still pursued)by the regional Superintencency suffersfrom many shortcomings:

• ‘Surface stripping by caterpillar’ is selec-tive and inefficient in the detection of cer-tain types of evidence, especially negativefeatures such as ditches, pits and sometypes of graves etc.

• This is an anachronistic approach to ar-chaeology, site-based or even worsefind-based or ‘object-based’. It takes noaccount of the cultural context (cultiva-tion patterns, field systems, infrastruc-ture, relationships etc) or ofenvironmental evidence (riverbeds,ridge-and-furrow cultivation etc.).

Moreover, it is important to emphasizethat this kind of ‘rescue archaeology’ ap-proach is the heritage of a culture that hasnever understood the wider significance ofthe change to a stratigraphic way of ‘thin-king’ archaeology and of writing history –based primarily on the observation of rela-tionships and not the recovery of individualobjects. Deprived of their original context,after all, such objects lose virtually all oftheir potential meaning. The strategy imple-mented in the BREBEMI project, as well asin other case studies elsewhere, representsthe concrete expression of the transpositioninto the landscape context of this stratigra-phic approach – one might almost say cul-ture. It matters little if here and there somedetails are lost – this is in no way differentfrom the situation on an archaeological ex-cavation if we fail to see or understand astratigraphical relationship. Undoubtedlythe loss of those details does not in itself in-validate the basic methodology.

Besides, we should highlight that thereare at least two other main issues related tocurrent rescue archaeology practice in Italy.

• Excavation by surface stripping has aninherent limitation: it is not repeatable,meaning that it is impossible to verifyhow much archaeology has been lost

• Moreover, this kind of approach produ-ces an unceasing ‘state of emergency’,generating stressful working conditionsthat are completely inimical to the effec-tive study, understanding and preserva-tion of the potentially availableevidence. This does not meet even theminimal requirements for making goodchoices and carrying out high-qualitywork.It is obvious, of course, that more expe-

rience and further case studies are neededand that the strategy, methodology and tech-nology put to work in the BREBEMI pro-ject could be improved upon. Nevertheless,in contrast with the outdated methods even-

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

78

tually imposed upon the motorway develop-ment, we feel that the approach that we tookin our work:

• matched up to the most advanced Euro-pean practice in the field of preventivearcheology;

• proved highly efficient, allowing us torecord objectively positive and negativeman-made features as well as naturalevidence, providing precise informationand a seamless continuity to a level ofdetail well adapted to the archeologicalrequirements;

• provided systematic, continuous and in-tegrated mapping of a broad range ofevidence;

• finally, our strategy was (and is) testable,repeatable, scientific and capable of refi-nement, in contrast to Superintendency’sapproach of ‘excavation by surface strip-ping’ which inevitably triggers a short-cir-cuit in any cycle of research.It has to be admitted, of course, that the

academic sphere suffers from its own short-comings. Academic research in landscapearchaeology is largely based on remote sen-sing, survey by field-walking and surfacecollection, and archaeological excavationaimed at securing detailed information ofparticular kinds or at particular locations. Atthe same time, before we can commit our-selves to the inevitably destructive processof excavation, we need a firm indication ofthe existence of buried archaeology. As a re-sult within academic archaeology generallywe do not excavate where the prospectiondata is mute. It is essential at this point tostress the completely different perspectivetaken by ‘preventive’ archaeology. We canof course apply the same kinds of strategiesand methods that we use in academic rese-arch, but there is a fundamental difference:the whole of the endangered area will comeunder excavation of one sort or anothereven if the archaeologist’s usual surveytools have failed to reveal positive evidence

of buried archaeology. The difference in afew words is that academics excavate onlywhere some specific evidence is available,with the result that they almost never syste-matically test areas where the basic surveymethods have failed to produce positive evi-dence of settlement or other kinds of humanactivity.

For instance in the BREBEMI case study– probably using the highest intensity of sur-vey techniques available at the time – we mayinevitably find that some important evidenceof human activity escaped our search, asmight have been the case with some forms ofburial and with other activities that left onlythe most ephemeral of evidence.

The opportunity for systematic verifica-tion of the prospection datasets should beproperly recognized, at least from the metho-dological point of view, as the main cha-llenge and at the same time the greatestopportunity. Thanks to the possibility of ve-rifying the correspondence (or otherwise)between massive datasets and thousands ofhectares of archaeological excavation, themethods of archaeological prospection andof excavation could be greatly improved in arelatively short time. It is possible for ins-tance to go back to the data and to checkwhether problems of apparent non-detectionare related to instrument sensitivity or reso-lution, or perhaps derive instead from somemisunderstanding or omission in data inter-pretation [7]. Another interesting approach tothis kind of issue suggested from pioneeringexperiences in the UK and Italy [8] is the im-plementation of geophysical survey after re-moval of the plough-soil (Figure 7). It is widely recognized that topsoil representsthe main source of noise in geophysical data.Moreover some methods, such as magneto-metry, gain greatly from a reduction in thedistance between the sensor and ‘discontinui-ties’ in the subsoil. The example presented inFigure 7 shows clearly the potential of ge-ophysical methods for providing opportuni-

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

79Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

ties to document and explain the evolution oflarge areas and relatively complex societies.Serious attention is needed to both of thesepossibilities. The opportunity for systematicand large scale ground-truthing through thekind of large-scale excavation work which fo-llowed the geophysical survey at Cook’sQuarry can present the archaeologist with thechance to learn and understand more aboutissues of archaeological visibility, ‘emptiness’and the inevitable but sometimes unackno-wledged limitation of our current remote sen-sing techniques.

PostscriptSadly, the regional Superintendent for Lom-bardy, Dr Raffaella Poggiani Keller – as isher right within the present organizationalstructure in Italy – ignored the NationalCommittee’s opinion, suspending furtherwork by the BREBEMI consultancy andapplying her own method of surface strip-ping to the rest of the motorway. On thebasis of this example it will clearly taketime for more advanced methods to attain awidespread application elsewhere. Never-theless, through the impact of the new law

and the example of this and other projectsover the past few years the ground has surely been prepared for a culture-change inthe official approach to preventive and res-cue archaeology within Italy.

Implications for the management ofWorld heritage sitesIt might be asked what relevance this has tothe management of World Heritage sites. Theanswer is that even within these areas someforms of destructive development occasio-nally become necessary to meet the needs ofpresent-day society. Whenever this happens,as it inevitably will, the need for a carefullystructured and meticulously executed ‘pre-ventive’ approach is absolutely vital, as is theconduct of any resulting excavations to thevery highest standards of stratigraphical ex-cavation. Only in this way will it be possibleto preserve, or to recover through excavation,the hidden archaeological evidence that is anessential part of any designated World Heri-tage site.

AcknowledgmentsThe author owes a huge debt of gratitude to

Figure 7. Left: the apparently blank survey of an area at Cook’s Quarry, West Heslerton, in the UK,

shows almost nothing before removal of the plough-soil. Right: by contrast, the re-survey after re-

moval of the plough-soil reveals clear evidence of a circular ‘hengiform’ structure, a Bronze Age

trackway and a Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age field system. (Reproduced by courtesy of Prof Do-

minic Powlesland, Landscape Research Centre, West Yorkshire, UK.)

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

80

the late Professor Riccardo Francovich, ofthe University of Siena, who gave him thecultural background and the intellectual vi-gour to face a challenge like that of theBREBEMI project. Special thanks are alsodue to two good friends who have followedand inspired so much of the writer’s research work since early in his career,Chris Musson and Prof Dominic Powles-land from the UK; as ever, they helped withconstructive criticism and commentsthroughout all stages of the project.

Sincere thanks are also due to the BRE-BEMI company for the great opportunityand trust provided by the president Dr Fran-cesco Bettoni, the general director ProfBruno Bottiglieri, the chief of the rescue ar-chaeology bureau Dr Paola Rigobello andthe company’s chief engineer Dr LorenzoFoddai. The author is further indebted to theSoIng company, in particular to AnnalisaMorelli, Gianfranco Morelli and GiovanniBitella, as well as to Iacopo Nicolosi at theItalian National Institute of Geophysics andVulcanology. Grateful thanks also go toKlaus Leidorf of Luftbilddocumentazion inGermany. All of these friends and collea-gues contributed to the successful conductand management of the field investigationsand to the overall outcome of the project.

Special thanks are also due to the teamof the Laboratory of Landscape Archaeo-logy and Remote Sensing at the Universityof Siena and of the spin-off company ATSEnterprise: Cristina Felici, Matteo Sordini,Francesco Pericci, Lorenzo Marasco, Bar-bara Frezza, Anna Caprasecca and Fran-cesco Brogi.

Finally, heartfelt thanks also go to the pre-sident of the Superior Consiluim of CulturalHeritage Prof Andrea Carandini, to directorProf Giuseppe Sassetelli and the members ofthe Scientific Committee for Italian Archaeo-logy, and lastly to the General Director of theSuperintendency, Dr Stefano De Caro, for pro-viding the opportunity to discuss our project

and for having the courage to present a reportwhich will hopefully see the start of a culturalrevolution in Italian archaeology, moving fromreactive rescue archaeology to a real ‘preven-tive’ approach.

References[1] Guzzo, P. G. (2000): Legislazione e tu-

tela. In Francovich, R. & Manacorda,D. (Eds.). Dizionario di Archeologia(pp. 177-183). Bari.Guermandi, M. P. (Ed.). (2001): Ris-chio Archeologico: se lo conosci loeviti. Atti del convegno di studi su car-tografia archeologica e tutela del terri-torio, Ferrara, 24-25 marzo 2000.Firenze.Ricci, A. (1996): I mali dell’abbon-danza. Considerazioni impolitiche suibeni culturali. Roma.Ricci, A. (2006): Attorno alla nudapietra. Archeologia e città tra identitàe progetto. Roma.

[2] Carandini, A. (2008): Archeologia Clas-sica. Vedere il tempo antico con gliocchi del 2000. Turin: Einaudi.

[3] Campana, S. & Piro, S. (2009): Seeingthe Unseen. Geophysics and Lands-cape Archaeology. Proceeding of theXVth International Summer School.London: Taylor & Francis.Dabas, M. (1999a). Diagnostic et éva-luation du potentiel archéologiquedans le cadre des tracés linéaires: ap-port des Systèmes d’Information Géo-graphiques. Revue d’Archéométrie 23,5-16.Dabas, M. (1999b): Contribution de laprospection géophysique à large mai-lle et de la géostatistique à l’étude destracés autoroutiers. Application aux fe-rriers de la Bussière sur l’A77. Revued’Archéométrie 5, 17-32.

[4] Dabas, M. (2009): Theory and practiceof the new fast electrical imagingsystem ARP©. In Campana S., S.Piro

Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional de Buenas Prácticas

en Patrimonio Mundial:Arqueología 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

Archaeological Impact Assessment vs Rescue Archaeology...S. Campana

81Proceedings of the First International Conference on Best

Practices in World Heritage: Archaeology 66-81

ISBN: 978-84-695-6782-1

(Eds.). Seeing the Unseen. Geophysicsand Landscape Archaeology. Procee-ding of the XVth International SummerSchool (pp. 105-126). London: Taylor& Francis.Powlesland, D. J. (2006): Redefiningpast landscapes: 30 years of remote sen-sing in the Vale of Pickering. In Cam-pana, S. & Forte, M. (Eds.). From Spaceto Place. Proceeding of the IInd Interna-tional Conference on Remote SensingArchaeology. Rome 4-7 December 2006(pp. 197-201). Oxford UK: Archaeo-press BAR International Series.Powlesland, D. J. (2009): Why bother?Large scale geomagnetic survey and thequest for ‘Real Archaeology’. In Cam-pana, S. & Piro, S. (Eds.). Seeing the Un-seen. Geophysics and LandscapeArchaeology (pp. 167-182). London:Taylor & Francis.

[5] Poggiani Keller, R. (Ed.). (1992): CartaArcheologica della Lombardia, II. LaProvincia di Bergamo. Voll.1,2,3(Saggi, Schede, Cartografia). Modena.

[6] Campana, S. (2009): Archaeological SiteDetection and Mapping: some thoughtson differing scales of detail and ar-chaeological ‘non-visibility’. In S.Campana & S. Piro (Eds.), Seeing theUnseen. Geophysics and LandscapeArchaeology. Proceeding of the XVth In-ternational Summer School (pp. 5-26).London: Taylor & Francis. Guaitoli, M.(Ed.). (1997). Metodologie di cataloga-zione dei beni archeologici. Bari.

[7] Hargrave, M. L. (2006): Ground Tru-thing the Results of Geophysical Sur-vey. In Johnson, J. K. (Ed.), RemoteSensing in Archaeology. An ExplicitlyNorth American Perspective (pp. 269-319). Tuscaloosa: The University ofAlabama Press.

[8] Lyall, J., Powlesland, D. J. (1996): Theapplication of high resolution fluxgategradiometery as an aid to excavation

planning and strategy formulation. In-ternet Archaeology 1,http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue1/index.html

Campana, S., Piro, R., & Felici, C.(2005): Integration between magneticsurveys and archaeological excavations:the case study Pava (Siena, Central Italy).In Proceedings of the 6th InternationalConference on Archaeological Prospec-tion, (Roma 14-17 settembre 2005)(pp.226-227). Rome: Institute of Techno-logies Applied to Cultural Heritage.