Salutogenesi versus paradigma prometeico della scienza medica

-

Upload

pier-paolo-dal-monte -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

108 -

download

1

Transcript of Salutogenesi versus paradigma prometeico della scienza medica

Salutogenesi versus paradigma prometeico della scienza medica

Pier Paolo Dal Monte, MD Bologna, Italy

Board member Associazione Italiana di Bioetica Chirurgica

!"#$%&"'()*&+$,)-.,$,)*,)/,.(-%$$&)0($(..,&)123",14&)"3").2(-0,--,5,$,6)(-7&..,)&7,*&0,3$3+,1,8)0&*,1,)&*)&13"30,139-31,($,

:%*,.32,%0

!"##$%&'()"*

;,()<(2+(8)=)>)?3$3+"()

+$'$#,-%..%"!!"/#$%01.2

)#$3(,$'45)678%#9:78;9%,<=%>9?;7)@) )*,)A",B($%.&8)?3$3+"(

@5A&*!B%5=:78;9%58=9;;6)@)B&2/,',3)B(",.C)D%55$,1()*&$$()E&+,3"&)F0,$,(9E30(+"(8)?3$3+"(><86<%*C6D<%/8<?E6)@)AGHG)*,)I&*,1,"()!".&2"(8)):',&"*()H-7&*($,&2()J(2&++,8)K,2&"'&F69G<??6%/6DD9?6)@)D2&-,*&".&)*&$$L:+&GM(GB)>):+&"',())M(',3"($&)7&2),)B&2/,',)B(",.(2,)E&+,3"($,8)E30(3<=G<;987%A<89??<)@)N&7%.(.3)($)D(2$(0&".3)F%237&38)?2%O&$$&-(G<?%A<G6HHI6)@)K(13$.C)*,)I&*,1,"()&)J4,2%2+,()*&$$LA",/&2-,.C))*,)P32);&2+(.(8)E30(

)@)I3GDG!G)I3/,0&".3)D-,13$3+,)!"*,7&"*&".,8)K,2&"'&)678%)<9=9%,<=%>9?;7)@):--31,(',3"&)!.($,("()*,)?,3&.,1()J4,2%2+,1(Q));,$$($5()R3-7,.($)*,)?3$3+"(5?;9?69%E7%/7=G6D)@)!-.,.%.3)B%7&2,32&)*,)B(",.C)D%55$,1(8))A",/&2-,.C)J(..3$,1()B(123)J%32&8)E30(,<?67=7%,7J=6%(??9H7?;6)@)K(13$.C)*,)I&*,1,"()&)J4,2%2+,(8))A",/&2-,.C)*,);&23"(*79?<8E9%@<::86)@)N,7(2.,0&".3)(*)(..,/,.C),".&+2(.()*,)H"13$3+,(8)F0(.3$3+,()&)D(.3$3+,&)*&$$L:77(2(.3)2&-7,2(.32,38))A",/&2-,.C)*&+$,)B.%*,)I3*&"()&)E&++,3)F0,$,()36K9?<%F6<KL<9=6)@)!-.,.%.3)B%7&2,32&)*,)B(",.C)*,)E30()6?<%*<==6)@)N,7(2.,0&".3)*,)B1,&"'&)D3$,.,14&)&)B31,($,8))A",/&2-,.C)*,)?3$3+"(@<:86M69%*CLL6)@):',&"*()H-7&*($,&2(9A",/&2-,.(2,()*,)I3*&"(A<8=9%*CD7?;6)@):--&--32&)($$&)D3$,.,14&)7&2)$()-($%.&))*&$$()E&+,3"&)F0,$,(9E30(+"(8)?3$3+"(N<=;78%><889HH9)@)BG!GIGDG&)BG;G)>)K,00+)SB31,&.C)!.($,("()*,)I&*,1,"()*,)D2&/&"',3"&)&)*&+$,)B.,$,)*,);,.(T><8H9%><8;CMM6)@)H2+(",''(',3"&)I3"*,($&)*&$$()B(",.CG)J&".23)F%237&3):05,&".&)&)B($%.&8)?3""#<6K9?E9%)<G<86?)@)H--&2/(.32,3)F7,*&0,3$3+,13))0&.2373$,.("3)*,7&"*&"'&)7(.3$3+,14&8):',&"*()A-$)?3$3+"(F69G<??6%)786?6)@)N,7(2.,0&".3)*,)K(20(1,()&)?,3.&1"3$3+,&8))A",/&2-,.C)*,)?3$3+"('6H9=<%)6?7==6)@)K&*&2(',3"&)!.($,("():',&"*&)B(",.(2,&))&)H-7&*($,&2&8)E30(>98<?E9%39OO86;;6)@)!-.,.%.3)E(0('',",8)?3$3+"(><8H%!<8<:7==<)@)N&7%.(.3)($)D(2$(0&".3)F%237&38)?2%O&$$&-)3;7O<?9%&8:6?<;6)@)A",.C)H7&2(.,/()*,)J(2*,3$3+,(8))H-7&*($&)?&$$(2,(8)?3$3+"(

('@"#>54("'(%F$'$#5*(

(3A#(4("'$*<% L<8;7H6L<M69?7% <=% A9?G7J?9% P% J8<;C6;<73-.,)*,-73",5,$,8)72&/,()2&+,-.2(',3"&)-%$)-,.3)QQQR?97K<H9?J87DD6R6;G

3$,$%5CE6;986CK%!9887%&?6L9=;,()<(2+(8)=)?3$3+"(

A">$%#5FF(&'F$#$%*5%3$,$S) ('%5&!"/&3) N($)1&".23)*,)?3$3+"()U)2(++,%"+,5,$&)13")$()$,"&()VWG

S) ('%5&!"3!#5,5) N()I,$("38)D(*3/()&)K,2&"'&)%-1,.()X?3$3+"()>):213/&++,3YG)D23-&9+%,2&)-%$$().("+&"',($&),")*,2&',3"&)X:"13"()>)B(")<(''(23)*,)B(/&"(Y)

) N():"13"()%-1,.() X?3$3+"()>)B(")<(''(23) *,)B(/&"(YG)D23-&+%,2&)

) <()P322&)A",73$)*,-.()7314,)0&.2,)*($$L%-1,.()*&$$().("+&"',($&G

5AA#$,(!5>$'!"%$A><L&/&".3)U)-.(.3)(112&*,.(.3)*($)D23/,*&2)M3&0()-2$)A",7&2-3"($&)S"G=ZVT8)MG) &/&".3)EFB) [Z[VVG) !$) J3"/&+"3) U) 2,/3$.3) ($$&) 1(.&+32,&) *,)I&*,13))J4,2%2+38) !"#&20,&2&8) H*3".3,(.2(8) K(20(1,-.(8) ;&.&2,"(2,38) D-,13$3+38)?,3$3+38) :--,-.&".&) B(",.(2,38) N,&.,-.(8) F*%1(.32&) D23#&-)-,3"($&8)K,-,3.&2(7,-.(8)P&1",13) *&$$() 72&/&"',3"&) "&$$L(05,&".&) &) "&,) $%3+4,) *,)$(/3238)P&1",13)*&$$()2,(5,$,.(',3"&)7-,14,(.2,1()&)P&2(7,-.()311%7(',3"($&G)D&2) 72&"*&2&) /,-,3"&) *&$$&) *,-1,7$,"&) (112&*,.(.&) 7&2) 3+",) 1(.&+32,()723#&--,3"($&)U)73--,5,$&)13"-%$.(2&)$L&$&"13)7%55$,1(.3)-%$)-,.3)*,)M3&0()>)QQQR?97K<H9?J87DD6R6;) &) -%$) -,.3) *&$$L:+&G"(G-G>)QQQR<J7?<DR6;)"&$$()7(+,"()*&*,1(.()($$L(112&*,.(0&".3)*&$)13"/&+"3G)39?9% D;<;6% <;;86:C6;6% ?R% 2TU% H87E6;6% O98K<;6G6) 14&) /&22(""3) &23+(.,) (,))7(2.&1,7(".,)14&)"&)#(2(""3)2,14,&-.(8)72&/,(6S) 13"-&+"()($$()-&+2&.&2,()32+(",''(.,/()*&$)0(.&2,($&)FJI))1307,)$(.3),")3+",)-%()7(2.&Q

S)S) )($)\%&)-.,3"(2,3G

M3") -(2(""3) 72&/,-.&) *&23+4&) () .($,) 355$,+4,) 7&2) $() 13"-&+"() *&$)

5!!$3!5!"%,(%)5#!$A()54("'$%<L(..&-.(.3) *,) 7(2.&1,7(',3"&) /&22C) 2,$(-1,(.3) *($$() B&+2&.&2,() (,)7(2.&1,7(".,)($).&20,"&)*&,)$(/32,G

!"#$%&"'()*&+$,)-.,$,)*,)/,.(-%$$&)0($(..,&)123",14&)"3").2(-0,--,5,$,6)(-7&..,)&7,*&0,3$3+,1,8)0&*,1,)&*)&13"30,139-31,($,

!"#$%&"'()*&+$,)-.,$,)*,)/,.(-%$$&)0($(..,&)123",14&)"3").2(-0,--,5,$,6)(-7&..,)&7,*&0,3$3+,1,8)0&*,1,)&*)&13"30,139-31,($,

!"#$%&"'()*&+$,)-.,$,)*,)/,.(-%$$&)0($(..,&)123",14&)"3").2(-0,--,5,$,6)(-7&..,)&7,*&0,3$3+,1,8)0&*,1,)&*)&13"30,139-31,($,

:%*,.32,%0

!"##$%&'()"*

;,()<(2+(8)=)>)?3$3+"()

+$'$#,-%..%"!!"/#$%01.2

)#$3(,$'45)678%#9:78;9%,<=%>9?;7)@) )*,)A",B($%.&8)?3$3+"(

@5A&*!B%5=:78;9%58=9;;6)@)B&2/,',3)B(",.C)D%55$,1()*&$$()E&+,3"&)F0,$,(9E30(+"(8)?3$3+"(><86<%*C6D<%/8<?E6)@)AGHG)*,)I&*,1,"()!".&2"(8)):',&"*()H-7&*($,&2()J(2&++,8)K,2&"'&F69G<??6%/6DD9?6)@)D2&-,*&".&)*&$$L:+&GM(GB)>):+&"',())M(',3"($&)7&2),)B&2/,',)B(",.(2,)E&+,3"($,8)E30(3<=G<;987%A<89??<)@)N&7%.(.3)($)D(2$(0&".3)F%237&38)?2%O&$$&-(G<?%A<G6HHI6)@)K(13$.C)*,)I&*,1,"()&)J4,2%2+,()*&$$LA",/&2-,.C))*,)P32);&2+(.(8)E30(

)@)I3GDG!G)I3/,0&".3)D-,13$3+,)!"*,7&"*&".,8)K,2&"'&)678%)<9=9%,<=%>9?;7)@):--31,(',3"&)!.($,("()*,)?,3&.,1()J4,2%2+,1(Q));,$$($5()R3-7,.($)*,)?3$3+"(5?;9?69%E7%/7=G6D)@)!-.,.%.3)B%7&2,32&)*,)B(",.C)D%55$,1(8))A",/&2-,.C)J(..3$,1()B(123)J%32&8)E30(,<?67=7%,7J=6%(??9H7?;6)@)K(13$.C)*,)I&*,1,"()&)J4,2%2+,(8))A",/&2-,.C)*,);&23"(*79?<8E9%@<::86)@)N,7(2.,0&".3)(*)(..,/,.C),".&+2(.()*,)H"13$3+,(8)F0(.3$3+,()&)D(.3$3+,&)*&$$L:77(2(.3)2&-7,2(.32,38))A",/&2-,.C)*&+$,)B.%*,)I3*&"()&)E&++,3)F0,$,()36K9?<%F6<KL<9=6)@)!-.,.%.3)B%7&2,32&)*,)B(",.C)*,)E30()6?<%*<==6)@)N,7(2.,0&".3)*,)B1,&"'&)D3$,.,14&)&)B31,($,8))A",/&2-,.C)*,)?3$3+"(@<:86M69%*CLL6)@):',&"*()H-7&*($,&2(9A",/&2-,.(2,()*,)I3*&"(A<8=9%*CD7?;6)@):--&--32&)($$&)D3$,.,14&)7&2)$()-($%.&))*&$$()E&+,3"&)F0,$,(9E30(+"(8)?3$3+"(N<=;78%><889HH9)@)BG!GIGDG&)BG;G)>)K,00+)SB31,&.C)!.($,("()*,)I&*,1,"()*,)D2&/&"',3"&)&)*&+$,)B.,$,)*,);,.(T><8H9%><8;CMM6)@)H2+(",''(',3"&)I3"*,($&)*&$$()B(",.CG)J&".23)F%237&3):05,&".&)&)B($%.&8)?3""#<6K9?E9%)<G<86?)@)H--&2/(.32,3)F7,*&0,3$3+,13))0&.2373$,.("3)*,7&"*&"'&)7(.3$3+,14&8):',&"*()A-$)?3$3+"(F69G<??6%)786?6)@)N,7(2.,0&".3)*,)K(20(1,()&)?,3.&1"3$3+,&8))A",/&2-,.C)*,)?3$3+"('6H9=<%)6?7==6)@)K&*&2(',3"&)!.($,("():',&"*&)B(",.(2,&))&)H-7&*($,&2&8)E30(>98<?E9%39OO86;;6)@)!-.,.%.3)E(0('',",8)?3$3+"(><8H%!<8<:7==<)@)N&7%.(.3)($)D(2$(0&".3)F%237&38)?2%O&$$&-)3;7O<?9%&8:6?<;6)@)A",.C)H7&2(.,/()*,)J(2*,3$3+,(8))H-7&*($&)?&$$(2,(8)?3$3+"(

('@"#>54("'(%F$'$#5*(

(3A#(4("'$*<% L<8;7H6L<M69?7% <=% A9?G7J?9% P% J8<;C6;<73-.,)*,-73",5,$,8)72&/,()2&+,-.2(',3"&)-%$)-,.3)QQQR?97K<H9?J87DD6R6;G

3$,$%5CE6;986CK%!9887%&?6L9=;,()<(2+(8)=)?3$3+"(

A">$%#5FF(&'F$#$%*5%3$,$S) ('%5&!"/&3) N($)1&".23)*,)?3$3+"()U)2(++,%"+,5,$&)13")$()$,"&()VWG

S) ('%5&!"3!#5,5) N()I,$("38)D(*3/()&)K,2&"'&)%-1,.()X?3$3+"()>):213/&++,3YG)D23-&9+%,2&)-%$$().("+&"',($&),")*,2&',3"&)X:"13"()>)B(")<(''(23)*,)B(/&"(Y)

) N():"13"()%-1,.() X?3$3+"()>)B(")<(''(23) *,)B(/&"(YG)D23-&+%,2&)

) <()P322&)A",73$)*,-.()7314,)0&.2,)*($$L%-1,.()*&$$().("+&"',($&G

5AA#$,(!5>$'!"%$A><L&/&".3)U)-.(.3)(112&*,.(.3)*($)D23/,*&2)M3&0()-2$)A",7&2-3"($&)S"G=ZVT8)MG) &/&".3)EFB) [Z[VVG) !$) J3"/&+"3) U) 2,/3$.3) ($$&) 1(.&+32,&) *,)I&*,13))J4,2%2+38) !"#&20,&2&8) H*3".3,(.2(8) K(20(1,-.(8) ;&.&2,"(2,38) D-,13$3+38)?,3$3+38) :--,-.&".&) B(",.(2,38) N,&.,-.(8) F*%1(.32&) D23#&-)-,3"($&8)K,-,3.&2(7,-.(8)P&1",13) *&$$() 72&/&"',3"&) "&$$L(05,&".&) &) "&,) $%3+4,) *,)$(/3238)P&1",13)*&$$()2,(5,$,.(',3"&)7-,14,(.2,1()&)P&2(7,-.()311%7(',3"($&G)D&2) 72&"*&2&) /,-,3"&) *&$$&) *,-1,7$,"&) (112&*,.(.&) 7&2) 3+",) 1(.&+32,()723#&--,3"($&)U)73--,5,$&)13"-%$.(2&)$L&$&"13)7%55$,1(.3)-%$)-,.3)*,)M3&0()>)QQQR?97K<H9?J87DD6R6;) &) -%$) -,.3) *&$$L:+&G"(G-G>)QQQR<J7?<DR6;)"&$$()7(+,"()*&*,1(.()($$L(112&*,.(0&".3)*&$)13"/&+"3G)39?9% D;<;6% <;;86:C6;6% ?R% 2TU% H87E6;6% O98K<;6G6) 14&) /&22(""3) &23+(.,) (,))7(2.&1,7(".,)14&)"&)#(2(""3)2,14,&-.(8)72&/,(6S) 13"-&+"()($$()-&+2&.&2,()32+(",''(.,/()*&$)0(.&2,($&)FJI))1307,)$(.3),")3+",)-%()7(2.&Q

S)S) )($)\%&)-.,3"(2,3G

M3") -(2(""3) 72&/,-.&) *&23+4&) () .($,) 355$,+4,) 7&2) $() 13"-&+"() *&$)

5!!$3!5!"%,(%)5#!$A()54("'$%<L(..&-.(.3) *,) 7(2.&1,7(',3"&) /&22C) 2,$(-1,(.3) *($$() B&+2&.&2,() (,)7(2.&1,7(".,)($).&20,"&)*&,)$(/32,G

!"#$%&"'()*&+$,)-.,$,)*,)/,.(-%$$&)0($(..,&)123",14&)"3").2(-0,--,5,$,6)(-7&..,)&7,*&0,3$3+,1,8)0&*,1,)&*)&13"30,139-31,($,

!"#$%&"'()*&+$,)-.,$,)*,)/,.(-%$$&)0($(..,&)123",14&)"3").2(-0,--,5,$,6)(-7&..,)&7,*&0,3$3+,1,8)0&*,1,)&*)&13"30,139-31,($,

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Dipinte in queste riveSon dell'umana genteLe magnifiche sorti e progressive G.Leopardi, La ginestra

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Fonte: Jim Oeppen and James W. Vaupel Science 10 May 2002

Fonte: Angus Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics (Paris: OECD, 2003); 2002–2003 data: World Bank.

very concepts of macroeconomics and (cyclical)

stabilization policy are essentially twentieth-

century creations—this topic has been dealt with

extensively in earlier World Economic Outlooks.

This chapter incorporates some of the many

insights contained in two supporting studies

commissioned for the World Economic Outlook.1

“Globalization and Growth in the Twentieth

Century” (IMF Working Paper 00/44), by

Professor Nicholas Crafts of the London School

of Economics, discusses real developments dur-

ing the twentieth century and was particularly

important for the discussion of growth and di-

vergence. “The International Monetary System

in the (Very) Long Run” (IMF Working Paper

00/43), by Professors Barry Eichengreen and

Nathan Sussman of the University of California

Berkeley and Hebrew University Jerusalem, re-

spectively, provides an overview of the interna-

tional monetary system over the last thousand

years, and was particularly important for the

discussion of the changing nature of interna-

tional monetary relations in the twentieth

century.

Global Economic Growth and IncomeDistribution

The two most striking characteristics of

twentieth-century economic growth are its stag-

gering size and acceleration when compared

with developments in previous centuries, and its

uneven distribution among different countries

and regions of the world.

Growth of Output and Population

Using conventional GDP estimates over a long

historical period, the total amount of goods and

services produced in the twentieth century is es-

timated to have exceeded the cumulative total

output over the preceding recorded human his-

CHAPTER V THE WORLD ECONOMY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

150

Real GDP and Population(1900 = 100)

Growth in 50-Year Intervals(period total, in percent)

Real GDP

Population

GDP Population

2000

1600

1200

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

400

01750

1700–50 1750–1800 1800–50 1850–1900 1900–50 1950–2000

1800 1850 1900 1950 2000

Figure 5.1. World GDP and Population Since 1750

During the twentieth century both output and population growth increased. However, as a result of accelerating technical progress, output growth increasingly exceeded population growth.

Source: Bradford J. DeLong, “Estimating World GDP, One Million B.C.–Present.” Available via the internet at: http://econ161.berkeley.edu.

1In addition to being issued as IMF Working Papers,

both studies are being published in World Economic

Outlook: Supporting Studies 2000 (Washington: IMF,

forthcoming).

Anatomia di un secolo

Speranza di vita alla nascita (paesi OCSE)

domenica 30 novembre 2014

1. HEALTH STATUS

HEALTH AT A GLANCE 2011: OECD INDICATORS © OECD 2011 25

1.1. Life expectancy at birth

1.1.1 Life expectancy at birth, 2009 (or nearest year), and years gained since 1960

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; World Bank and national sources for non-OECD countries.1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932523253

405060708090 0 5 10 15 20 25 30

83.082.381.881.881.681.681.581.481.081.080.880.780.780.680.480.480.380.380.380.080.080.079.579.579.079.078.478.2

77.375.875.375.075.0

74.073.873.3

72.671.2

68.764.1

51.7

15.210.9

12.012.0

10.79.9

8.68.3

10.77.2

9.79.4

11.37.1

11.79.6

11.210.4

27.910.2

11.010.0

15.611.2

6.610.5

21.48.3

6.78.0

17.86.5

4.46.0

25.526.7

18.130.0

0.021.7

2.6

Life expectancy at birth, 2009 Years gained, 1960-2009

Years Years

JapanSwitzerland

ItalySpain

AustraliaIsrael

IcelandSwedenFranceNorway

New ZealandCanada

Luxembourg

OECDDenmark

NetherlandsAustria

United KingdomGermanyGreeceKorea

ChinaBrazil

SloveniaChile

United StatesCzech Republic

PolandMexicoEstonia

Slovak RepublicHungaryTurkey

BelgiumFinlandIreland

Portugal

IndonesiaRussian Federation

IndiaSouth Africa

1.1.2 Life expectancy at birth and GDP per capita, 2009 (or nearest year)

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; World Bank and national sources fornon-OECD countries.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932523272

0 10 000 20 000 30 000 40 000 50 000 60 000 70 000

84

80

76

72

68

64

JPNCHEITAESP

AUSISR

ISLSWE

NOR

FRANZL

LUXCAN

NLD

AUTGBR

DEU

GRCKOR

IRL

BEL

FIN

PRT

DNKSVN USACHLCZE

POL

MEX SVKEST

HUNTURCHN BRA

IDN

RUS

IND

R! = 0.54

GDP per capita (USD PPP)

Life expectancy in years

1.1.3 Life expectancy at birth and health spending per capita, 2009 (or nearest year)

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; World Bank and national sources fornon-OECD countries.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932523291

0 2 000 4 000 6 000 8 000

84

80

76

72

68

64

R! = 0.69

AUS

AUT

BEL

BRA

CAN

CHLCZE

DNK

EST

FINFRA

DEUGRC

HUN

ISL

IND

IDN

CHN

IRL

ISR ITA

JPN

KOR

LUX

MEX

NLDNZL NOR

POL

PRT

RUS

SVK

SVN

ESP SWE CHE

TUR

GBRUSA

Health spending per capita (USD PPP)

Life expectancy in years

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; World Bank and national sources for non-OECD countries

Anatomia di un secolo

domenica 30 novembre 2014

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

17.4

12.0

11.8

11.6

11.5

11.4

11.4

11.0

10.9

10.3

10.1

10.0

9.8

9.7

9.6

9.6

9.6

9.5

9.5

9.5

9.3

9.2

9.1

9.0

8.7

8.5

8.5

8.4

8.2

7.9

7.8

7.4

7.4

7.0

6.9

6.4

6.1

5.4

4.6

4.2

2.4

Public Private

% of GDP

United

States

Netherl

ands

1

Franc

e

German

y

Denmark

Canad

a

Switzerl

and

Austria

Belgium

2

New Ze

aland

Portug

al

Sweden

United

Kingdo

mIce

land

Greece

Norway

OECDIre

land

Italy

Spain

Sloven

ia

Finlan

d

Slovak

Repub

licBraz

il

Austra

liaJa

pan

South

Africa

Chile

Czech R

epub

licIsr

ael

Luxe

mbourg

3

Hunga

ry

Poland

Eston

iaKore

a

Mexico

Turke

y

Russia

n Fed

eratio

nChin

aInd

ia

Indon

esia

Total health expenditure as a share of GDP, 2009

OECD Health Data 2011; WHO Global Health Expenditure Database

Il costo della salute

domenica 30 novembre 2014

7. HEALTH EXPENDITURE AND FINANCING

HEALTH AT A GLANCE 2011: OECD INDICATORS © OECD 2011 151

7.2. Health expenditure in relation to GDP

7.2.1 Total health expenditure as a share of GDP, 2009 (or nearest year)

1. In the Netherlands, it is not possible to clearly distinguish the public and private share related to investments.2. Total expenditure excluding investments.3. Health expenditure is for the insured population rather than the resident population.

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; WHO Global Health Expenditure Database.1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932526103

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

17.4

12.0

11.8

11.6

11.5

11.4

11.4

11.0

10.9

10.3

10.1

10.0

9.8

9.7

9.6

9.6

9.6

9.5

9.5

9.5

9.3

9.2

9.1

9.0

8.7

8.5

8.5

8.4

8.2

7.9

7.8

7.4

7.4

7.0

6.9

6.4

6.1

5.4

4.6

4.2

2.4

Public Private

% of GDP

United

States

Netherl

ands

1

Franc

e

German

y

Denmark

Canad

a

Switzerl

and

Austria

Belgium

2

New Ze

aland

Portug

al

Sweden

United

Kingdo

mIce

land

Greece

Norway

OECDIre

land

Italy

Spain

Sloven

ia

Finlan

d

Slovak

Repub

licBraz

il

Austra

liaJa

pan

South

Africa

Chile

Czech R

epub

licIsr

ael

Luxe

mbourg

3

Hunga

ry

Poland

Eston

iaKore

a

Mexico

Turke

y

Russia

n Fed

eratio

nChin

aInd

ia

Indon

esia

7.2.2 Total health expenditure as a share of GDP, selected OECD countries, 2000-09

Source: OECD Health Data 2011.1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932526122

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

United StatesSwitzerlandCanada

OECDUnited KingdomKorea

% of GDP

7.2.3 Annual average growth in real per capita expenditure on health and GDP, 2000-09 (or nearest year)

Source: OECD Health Data 2011.1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932526141

-1 0 1 3 5

11

9

7

5

3

1

0

-1

SVK

KOR

ESTPOLGRC

TURIRLCZE

CHLNZL

GBR

NLDBEL

FINESPSVNCAN

SWEDNK

USAMEX AUS

HUNJPN

NOR

AUTFRA

DEU CHE ISLITAISRPRT

LUX

Annual average growth rate in real GDP per capita (%)

Annual average growth rate in real health expenditure per capita (%)

OECD

1. HEALTH STATUS

HEALTH AT A GLANCE 2011: OECD INDICATORS © OECD 2011 25

1.1. Life expectancy at birth

1.1.1 Life expectancy at birth, 2009 (or nearest year), and years gained since 1960

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; World Bank and national sources for non-OECD countries.1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932523253

405060708090 0 5 10 15 20 25 30

83.082.381.881.881.681.681.581.481.081.080.880.780.780.680.480.480.380.380.380.080.080.079.579.579.079.078.478.2

77.375.875.375.075.0

74.073.873.3

72.671.2

68.764.1

51.7

15.210.9

12.012.0

10.79.9

8.68.3

10.77.2

9.79.4

11.37.1

11.79.6

11.210.4

27.910.2

11.010.0

15.611.2

6.610.5

21.48.3

6.78.0

17.86.5

4.46.0

25.526.7

18.130.0

0.021.7

2.6

Life expectancy at birth, 2009 Years gained, 1960-2009

Years Years

JapanSwitzerland

ItalySpain

AustraliaIsrael

IcelandSwedenFranceNorway

New ZealandCanada

Luxembourg

OECDDenmark

NetherlandsAustria

United KingdomGermanyGreeceKorea

ChinaBrazil

SloveniaChile

United StatesCzech Republic

PolandMexicoEstonia

Slovak RepublicHungaryTurkey

BelgiumFinlandIreland

Portugal

IndonesiaRussian Federation

IndiaSouth Africa

1.1.2 Life expectancy at birth and GDP per capita, 2009 (or nearest year)

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; World Bank and national sources fornon-OECD countries.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932523272

0 10 000 20 000 30 000 40 000 50 000 60 000 70 000

84

80

76

72

68

64

JPNCHEITAESP

AUSISR

ISLSWE

NOR

FRANZL

LUXCAN

NLD

AUTGBR

DEU

GRCKOR

IRL

BEL

FIN

PRT

DNKSVN USACHLCZE

POL

MEX SVKEST

HUNTURCHN BRA

IDN

RUS

IND

R! = 0.54

GDP per capita (USD PPP)

Life expectancy in years

1.1.3 Life expectancy at birth and health spending per capita, 2009 (or nearest year)

Source: OECD Health Data 2011; World Bank and national sources fornon-OECD countries.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932523291

0 2 000 4 000 6 000 8 000

84

80

76

72

68

64

R! = 0.69

AUS

AUT

BEL

BRA

CAN

CHLCZE

DNK

EST

FINFRA

DEUGRC

HUN

ISL

IND

IDN

CHN

IRL

ISR ITA

JPN

KOR

LUX

MEX

NLDNZL NOR

POL

PRT

RUS

SVK

SVN

ESP SWE CHE

TUR

GBRUSA

Health spending per capita (USD PPP)

Life expectancy in years

Il costo della salute

OECD Health Data 2011; WHO Global Health Expenditure Database

Aspettativa di vita alla nascita e spese sanitarie 2009

Crescita annua delle spese sanitarie pro capite

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Illimitato progresso tecnologico (senza riguardo per i costi a lungo termine)

L’ innovazione tecnologica definisce gli obiettivi della sanità

(modifica continuamente i mezzi e i fini)

Il complesso medico-industriale guida il progresso e gli obiettivi della medicina

L’identità culturale della medicina moderna

Il modello contemporaneo è basato sul progresso infinito

Daniel Calllahan, Sustainable Medicine: Two Models of Health Care! ! Giannino Bassetti Foundation - 2005

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Visione lineare(Modello prometeico)

L’identità culturale, che è una specificità spazio-temporale,

diminuisce la possibilità di trovare modelli o soluzioni alternative

Il “cultural lock in”

domenica 30 novembre 2014

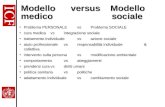

Il modello contemporaneo di medicina “scientifica”

Progresso tecnico e creazione di un massiccio complesso medico-industriale

Caratteristiche:

•Terapia invece che cura (cure rather than care)•Interventi tecnologici invece che promozione ! della !salute/prevenzione•Maggiore attenzione alle patologie acute che a quelle croniche•Paradigma quantitativo: durata piuttosto che qualità della vita

Daniel Calllahan, Sustainable Medicine: Two Models of Health Care! ! Giannino Bassetti Foundation - 2005

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Attualmente non esiste, in nessun paese, un Sistema Sanitario sostenibile

Aumento dellʼetà media e dei bisogni di curaAumento continuo del costo della tecnologia (con benefici marginali)

RisultatoRischio del crollo dellʼidea di Sistemi Sanitari “universali”

Se le cure non sono sostenibili non possono essere equamente distribuite

Discriminazione di censo

L’aporia del modello contemporaneo

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Tutto questo è fantastico, ma che cosa succederà se non potremo più permettercelo?

domenica 30 novembre 2014

USA, Ottobre 2013

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Sostenibilità: Legge dei ritorni marginali decrescenti

In economia, I ritorni marginali di un fattore di produzione in genere diminuiscono con l’aumento di input del fattore

medesimo!

David Ricardo. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817)

Decrescita del ritorno per aumento della complessità !! J. Tainter, The collapse of complex society 1988

Col 20% degli investimenti può essere ottenuto l’80% di successo; ma è necessario l’80% degli

investimenti per arrivare al 100%

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Produttività del sistema sanitario U.S.A. 1930-1982.

Indice di Produttività = Aspettativa di vita/ spese per la sanitàTainter, The collapse of complex society ,1988

Sostenibilità: Legge dei ritorni marginali decrescenti

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Crisi economica

Il nostro modello è sostenibile?

Scarsità materie prime

Sovrappopolazione

Cambiamento climatico

Guerre per le risorse

Disoccupazione

Migrazioni

Distruzione della biosferaPicco del petrolio

OTC 2009 Topical LuncheonHouston, Texas

Le esigenze dell’economia e quelle ecologiche sono radicalmente irreconciliabili Probabilmente sarebbe necessaria una depressione economica mondiale di entità

catastrofica per salvare la specie umana dal rischio di estinzione Philip Goodchild, Capitalism and religion, 2002

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Il caso della Russia dopo il crollo dell’Unione sovietica

Vladimir M. Shkolnikov, France Mesle:The Russian Epidemiological Crisis as Mirrored by Mortality TrendsIn: DaVanzo, Julie and Gwen Farnsworth. Russia's Demographic ''Crisis''. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1996.

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Anatomia di un secolo

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Anatomia di un secolo

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Condizioni di vita

IgieneAlimentazione

Tecnologia Medica

AntibioticiChirurgia asettica

Tecniche anestesiologiche

Aumento dell’aspettativa di vita XX secolo

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Poichè la malattia è universale, ogni società umana ha sviluppato un paradigma, una filosofia, una serie di

categorie per cercare di comprenderla.

Nelle moderne società industrializzate, esso si può definire cosiddetto “paradigma patogenetico”

Esso è alla base del complesso delle istituzioni sanitarie che abbiamo creato

Salutogenesi

Aaron Antonovsky, SALUTOGENESIS: STUDYING HEALTH VS. STUDYING DISEASE, 1990

www.salutogenesis.net A. Antonovsky . conference in Berlim 1

this is a www.salutogenesis.net initiative

post your message at

SALUTOGENESIS

EASESTUDYING DIS. STUDYING HEALTH VS Aaron Antonovsky

,Lecture at the Congress for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 1990 February 19, Berlin

Abstract

The paper's point of departure is the proposal that the pathogenic paradigm which at present dominates disease research and clinical practice in the industrialized world is of decreasing power as we try to understand and deal with the health and illness of human beings. The limitations of the paradigm are not resolved by preventive medicine or the biopsychosocial model. Five important contrasts are presented to show that the difference between the pathogenic and the salutogenic model, which posits that the great mystery is the origin of

health, are fundamental.

The search for the answer to the question "What explains movement toward the health end of the health/ illness continuum?" led to formulation of the sense of coherence concept and its three components, comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness. The overarching hypothesis, then, became: the stronger the SOC, the greater the likelihood of moving toward

the health end of the continuum.

The major determinants of the SOC are located in macrosocial and historical factors. Finally, it is noted that there are many roads to a strong SOC and health, and that health is not the only

value in human life.

domenica 30 novembre 2014

1. Come è classificato lo stato di salute delle persone?Classificazione dicotomica (salute/malattia) piuttosto che secondo un

continuum

2. Che cosa bisogna comprendere e trattare?Diagnosi specifica vs. valutazione dello stato di salute globale

3. Quali sono i fattori eziologici importanti?Fattori di rischio particolari vs. “storia” globale del paziente

4. Come sono concettualizzati i fattori di stress?Fattori inusuali e patogenetici vs fattori di ubiquitari e non direttamente

causali

5. Come trattare la sofferenza? Guerra coi “proiettili magici” contro la malattia vs rafforzamento delle

risorse personali

Salutogenesi

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Salute

Promotori di Malattia(esogeni e endogeni)

Inibitori di malattia(esogeni e endogeni

L’organismo umano è un sistema adattativo complesso (Prigogine: struttura dissipativa) ed è, quindi, soggetto all’entropia

Il vero mistero non è comprendere perchè le persone si ammalano e muoiono. Il vero mistero è capire perchè alcune persone hanno una salute migliore di altre

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Carta di Ottawa (1986): requisiti fondamentali per la salute

Pace Adeguate risorse economiche

Alimentazione Abitazione

Ambiente di lavoroSviluppo personale

Comunità Ecosistema stabile

Uso sostenibile delle risorse.

Salute

"Uno stato di completo benessere fisico, mentale e sociale e non la semplice assenza dello stato di malattia o di infermità." (WHO, 1948)

Inestricabili legami esistenti tra le condizioni socioeconomiche, l'ambiente fisico, lo stile di vita delle persone e la salute

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Occupational class differences in life expectancy, England and Wales, 1997–1999

Life expectancy is shorter and most diseases are more common further down the social ladder in each society. Health policy must tackle the social and economic determinants of health.

What is known

Poor social and economic circumstances affect health throughout life. People further down the social ladder usually run at least twice the risk of serious illness and premature death as those near the top. Nor are the effects confined to the poor: the social gradient in health runs right across society, so that even among middle-class office workers, lower ranking staff suffer much more disease and earlier death than higher ranking staff (Fig. 1).

Both material and psychosocial causes contribute to these differences and their effects extend to most diseases and causes of death.

Disadvantage has many forms and may be absolute or relative. It can include having few family assets, having a poorer education during adolescence, having insecure employment, becoming stuck in a hazardous or dead-end job, living in poor housing, trying to bring up a family in difficult circumstances and living on an inadequate retirement pension.

These disadvantages tend to concentrate among the same people, and their effects on health accumulate during life. The longer people live in stressful economic and social circumstances, the greater the physiological wear and tear they suffer, and the less likely they are to enjoy a healthy old age.

Policy implications

If policy fails to address these facts, it not only ignores the most powerful determinants of health standards in modern societies, it also ignores one of the most important social justice issues facing modern societies.

• Life contains a series of critical transitions: emotional and material changes in early childhood, the move from primary to secondary education, starting work, leaving home and starting a family, changing jobs and facing possible redundancy, and eventually retirement. Each of these changes can affect health by pushing people onto a more or less advantaged path. Because people who have been disadvantaged in the past are at the greatest risk in each subsequent transition, welfare policies need to provide not only safety nets but also springboards to offset earlier disadvantage.

10

Professional

Skilled non-manual

Managerial and technical

64LIFE EXPECTANCY (YEARS)

Skilled manual

Partly skilled manual

Unskilled manual

Men Women

66 68 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84

OCC

UPA

TIO

NA

L CL

ASS

1 . T H E S O C I A L G R A D I E N T

Fig. 1. Occupational class differences in life expectancy, England and Wales, 1997–1999

Donkin A, Goldblatt P, Lynch K. Inequalities in life expectancy by social class 1972–1999. Health

Statistics Quarterly, 2002

18

Stress in the workplace increases the risk of disease. People who have more control over their work have better health.

What is known

In general, having a job is better for health than having no job. But the social organization of work, management styles and social relationships in the workplace all matter for health. Evidence shows that stress at work plays an important role in contributing to the large social status differences in health, sickness absence and premature death. Several European workplace studies show that health suffers when people have little opportunity to use their skills and low decision-making authority.

Having little control over one’s work is particularly strongly related to an increased risk of low back pain, sickness absence and cardiovascular disease (Fig. 4). These risks have been found to be independent of the psychological characteristics of the people studied. In short, they seem to be related to the work environment.

Studies have also examined the role of work demands. Some show an interaction between demands and control. Jobs with both high demand and low control carry special risk. Some evidence indicates that social support in the workplace may be protective.

Further, receiving inadequate rewards for the effort put into work has been found to be associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Rewards can take the form of money, status and self-esteem. Current changes in the labour market may change the opportunity structure, and make it harder for people to get appropriate rewards.

These results show that the psychosocial environment at work is an important determinant of health and contributor to the social gradient in ill health.

Policy implications

• There is no trade-off between health and productivity at work. A virtuous circle can be established: improved conditions of work will lead to a healthier work force, which will lead to improved productivity, and hence to the opportunity to create a still healthier, more productive workplace.

• Appropriate involvement in decision-making is likely to benefit employees at all levels of an organization. Mechanisms should therefore be developed to allow people to influence the design and improvement of their work

Fig. 4. Self-reported level of job control and incidence of coronary heart disease in men and women

5 . W O R K

Adjusted for age, sex, length of follow-up, effort/reward imbalance, employment grade, coronary risk factors and negative psychological disposition

RISK

OF

CORO

NA

RY H

EART

DIS

EASE

(WIT

H H

IGH

JOB

CON

TRO

L SE

T AT

1.0

)

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

JOB CONTROL

High Intermediate Low

Self-reported level of job control and incidence of coronary heart disease

( opportunity to use skills and decision-making authority)

Bosma H et al. Two alternative job stress models and risk of coronary heart disease. American Journal of Public Health, 1998

Salute

domenica 30 novembre 2014

KEY SOURCES

27

Fig. 8. Mortality from coronary heart disease in relation to fruit and vegetable supply in selected European countries

Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003 (WHO Technical Report Series, No. 916) (http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/who_fao_expert_report.pdf, accessed 14 August 2003)

First Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy [web pages]. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2000 (http://www.euro.who.int/nutrition/ActionPlan/20020729_1, accessed 14 August 2003).

Roos G et al. Disparities in vegetable and fruit consumption: European cases from the north to the south. Public Health Nutrition, 2001, 4:35–43

Systematic reviews in nutrition. Transforming the evidence on nutrition and health into knowledge [web site]. London, University College London, 2003 (http://www.nutritionreviews.org/, accessed 14 August 2003).

World Cancer Research Fund. Food, nutrition and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC, American Institute for Cancer Research, 1997 (http://www.aicr.org/exreport.html, accessed 14 August 2003).

Source of Fig. 8: FAOSTAT (Food balance sheets) [database online]. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 25 September 2003.

WHO mortality database [database online]. Geneva, World Health Organization, 25 September 2003.

Health for all database [database online]. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 25 September 2003.

Policy implications

Local, national and international government agencies, nongovernmental organizations and the food industry should ensure:

• the integration of public health perspectives into the food system to provide affordable and nutritious fresh food for all, especially the most vulnerable;

• democratic, transparent decision-making and accountability in all food regulation matters, with participation by all stakeholders, including consumers;

• support for sustainable agriculture and food production methods that conserve natural resources and the environment;

• a stronger food culture for health, especially through school education, to foster people’s

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450

Greece

AG

E-ST

AN

DA

RDIZ

ED D

EATH

RA

TES

PER

100

000

MEN

AG

ED 3

5–74

SUPPLY OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLES (KG/PERSON/YEAR)

Ukraine

Russian Federation

Lithuania

Poland

Germany

FranceSpain

Belarus

knowledge of food and nutrition, cooking skills, growing food and the social value of preparing food and eating together;

• the availability of useful information about food, diet and health, especially aimed at children;

• the use of scientifically based nutrient reference values and food-based dietary guidelines to facilitate the development and implementation of policies on food and nutrition.

United Kingdom

Italy

Mortality from coronary heart disease in relation to fruit and vegetable supply in selected European countries

FAOSTAT (Food balance sheets) [database online]. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 25 September 2003.

KEY SOURCES

21

Beale N, Nethercott S. Job-loss and family morbidity: a study of a factory closure. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 1985, 35:510–514.

Bethune A. Unemployment and mortality. In: Drever F, Whitehead M, eds. Health inequalities. London, H.M. Stationery Office, 1997.

Burchell, B. The effects of labour market position, job insecurity, and unemployment on psychological health. In: Gallie D, Marsh C, Vogler C, eds. Social change and the experience of unemployment. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1994:188–212.

Ferrie J et al., eds. Labour market changes and job insecurity: a challenge for social welfare and health promotion. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 1999 (WHO Regional Publications, European Series, No. 81) (http://www.euro.who.int/document/e66205.pdf, accessed 15 August 2003).

Iversen L et al. Unemployment and mortality in Denmark. British Medical Journal, 1987, 295:879–884.

Source of Fig. 5: Ferrie JE et al. Employment status and health after privatisation in white collar civil servants: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal, 2001, 322:647–651.

Fig. 5. Effect of job insecurity and unemployment on health

Policy implications

Policy should have three goals: to prevent unemployment and job insecurity; to reduce the hardship suffered by the unemployed; and to restore people to secure jobs.

• Government management of the economy to reduce the highs and lows of the business cycle can make an important contribution to job security and the reduction of unemployment.

• Limitations on working hours may also be beneficial when pursued alongside job security and satisfaction.

Unemployed

RISK

OF

ILL

HEA

LTH

(WIT

H S

ECU

RELY

EM

PLO

YED

SET

AT

100)

Long-standing illness

Poor mental health

EMPLOYMENT STATUS

Securely employed

Insecurely employed

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

• To equip people for the work available, high standards of education and good retraining schemes are important.

• For those out of work, unemployment benefits set at a higher proportion of wages are likely to have a protective effect.

• Credit unions may be beneficial by reducing debts and increasing social networks.

Effect of job insecurity and unemployment on health

Ferrie JE et al. Employment status and health after privatisation in white collar civil servants: prospective cohort

study. British Medical Journal, 2001KEY SOURCES

25

Fig. 7. Socioeconomic deprivation and risk of dependence on alcohol, nicotine and drugs, Great Britain, 1993

Bobak M et al. Poverty and smoking. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, eds. Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000:41–61.

Makela P, Valkonen T, Martelin T. Contribution of deaths related to alcohol use of socioeconomic variation in mortality: register based follow-up study. British Medical Journal 1997, 315:211–216

Marsh A, McKay S. Poor smokers. London, Policy Studies Institute, 1994.

especially in the case of tobacco, has hampered efforts by governments to use price mechanisms to limit consumption.

Policy implications

• Work to deal with problems of both legal and illicit drug use needs not only to support and treat people who have developed addictive patterns of use, but also to address the patterns of social deprivation in which the problems are rooted.

• Policies need to regulate availability through pricing and licensing, and to inform people about less harmful forms of use, to use health education to reduce recruitment of young people and to provide effective treatment services for addicts.

• None of these will succeed if the social factors that breed drug use are left unchanged. Trying to shift the whole responsibility on to the user is clearly an inadequate response. This blames the victim, rather than addressing the complexities of the social circumstances that generate drug use. Effective drug policy must therefore be supported by the broad framework of social and economic policy.

Meltzer H. Economic activity and social functioning of residents with psychiatric disorders. London, H.M. Stationery Office, 1996 (OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity in Great Britain, Report 6).

Ryan, M. Alcoholism and rising mortality in the Russian Federation. British Medical Journal, 1995, 310:646–648.

Source of Fig. 7: Wardle J et al., eds. Smoking, drinking, physical activity and screening uptake and health inequalities. In: Gordon D et al, eds. Inequalities in health. Bristol, The Policy Press, 1999:213–239.

DEPRIVATION SCORE

RISK

OF

DEP

END

ENCE

(WIT

H M

OST

AFF

LUEN

T SE

T A

T 1)

Most affluent

Most deprived

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

00 1 2 3 4

Alcohol

Nicotine

Drugs

Socioeconomic deprivation and risk of dependence on alcohol, nicotine and drugs, Great Britain, 1993

Wardle J et al., eds. Smoking, drinking, physical activity and screening uptake and health inequalities. In: Gordon D et al,

eds. Inequalities in health. Bristol, 1999

Salute

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Metabolismo sociale

Processo economico (nel mondo reale)Processo termodinamico

Flusso di materia ed energia a bassa entropia

Flusso di materia ed energia ad alta entropia (inquinamento, rifiuti)

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Che cos’è la ricchezza?

La ricchezza (wealth) non è altro che materia ed energia in forme utilizzabili dagli uomini e dal metabolismo sociale

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Conflitto inevitabile tra concezione economica che richiede crescita esponenziale e mondo fisico

La crescita del consumo di materia/energia ha limiti finiti mentre la crescita monetaria (che è un’astrazione )

non ne ha alcuno

Economia astratta e “mondo fisico”

domenica 30 novembre 2014

La ricchezza reale (i beni) obbedisce alle leggi della termodinamica

Il denaro è un’unita di misura simbolica che può essere creata dal nulla e distrutta a piacimento

Non si può contrapporre un’assurda convenzione come l’incremento spontaneo del debito (interesse composto) alla legge naturale dello spontaneo decremento della ricchezza

(entropia) Frederick Soddy

Ricchezza reale e virtuale

domenica 30 novembre 2014

AlimentazioneValore d’uso

Proprietà nutrizionali

Proprietà organolettiche

Impatto ambientale

domenica 30 novembre 2014

• Privilegiare il Trasporto di persone e merci per nave e ferrovia (in ordine decrescente: acqua, ferro, asfalto)• Modificare la catena distributiva alimentare e prediligere il

cibo prodotto nelle vicinanze (filiera corta)• Favorire l’agricoltura biologica poichè necessita di minori

apporti di combustibili fossili• Limitare la produzione globalizzata che richiede il trasporto

delle merci per migliaia di chilometri

Matthew P. Simmons, Banchiere e consigliere strategico per l’energia di G.W.Bush

Suggerimenti per la sostenibilità

domenica 30 novembre 2014

L’energia fossile necessaria per una dieta mista è circa il doppio di quella necessaria per una dieta

vegetariana

!

Dieta vegetariana e dieta mista

domenica 30 novembre 2014

!

!

…..E così anche il tempo

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Più della metà dei cereali prodotti negli USA (40% nel mondo) usata per alimentazione animale (323 MT)

Pimentel and Pimentel,Food, Energy, and Society, CRC Press 2008)

Consumo cereali pro capite USA (1997): 1015 Kg116 consumo diretto, 615 alimentazione animale, 100

produzone birra, più altri usi (dolcificanti, melasse, ecc)

Consumo cereali pro capite nel mondo (1997): 345 kg160 consumo diretto, 185 altri usi

M. Giampietro,Multi-scale integrated analysis of agro-ecosystems, CRC Press 2004

L’impatto delle proteine animali

domenica 30 novembre 2014

!

Il “costo” delle proteine animali

domenica 30 novembre 2014

!

Consumo idrico nella produzione di alimenti (traspirazione)

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Undertaking primary prevention at the source to reduce health risks resulting from these global influences is a formidable challenge.

It requires conceptual insights beyond the conventional understanding of causation and prevention, as well as political will, trust, and

resources.

For populations to live sustainably and with good long-term health, the health sector must work with other sectors in reshaping how

human societies plan, build, move, produce, consume, share, and generate energy.

Globalization, Climate Change, and Human HealthAnthony J. McMichael, M.B., B.S., Ph.D. N Engl J Med 2013

Un concetto più ampio di “prevenzione”

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Il paradigma patogenetico è sempre meno efficace nel cercare di comprendere e trattare la malattia cronica. Le limitazioni di questo paradigma non sono risolte

neppure dalla medicina preventiva o dal modello psicosociale

Aaron Antonovsky, SALUTOGENESIS STUDYING HEALTH VS. STUDYING DISEASE, 1990

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Antonovsky “Sense of coherence”

Sense of coherence: Percezione di pienezza di significato della propria vita

Il SOC è possibile soltanto in una società che favorisca l’autonomia, la creatività, l’equanimità, il calore nelle relazioni

umane, la dignità e il rispetto delle persone

Aaron Antonovsky, SALUTOGENESIS STUDYING HEALTH VS. STUDYING DISEASE, 1990

Maggiore è il “sense of coherence” di una persona, più essa sarà in grado di far fronte agli invitabili fattori patogenetii

dellaesistenza

domenica 30 novembre 2014

Grazie per l’attenzione

domenica 30 novembre 2014

![Bollettino Notiziario - Salutogenesi · 2020. 11. 24. · Bollettino Notiziario - n° 10 ottobre 2020 • 15 [PRIMA PARTE] Note per la lettura: – laddove vengono riportati testi,](https://static.fdocumenti.com/doc/165x107/6104a7669bfa9300a6109838/bollettino-notiziario-salutogenesi-2020-11-24-bollettino-notiziario-n.jpg)