Renzo Piano

-

Upload

abhishek-behera -

Category

Documents

-

view

914 -

download

5

description

Transcript of Renzo Piano

ren

zo p

ian

o

abhishek behera

Renzo Piano was born into a family of

builders in Genoa, Italy in 1937.

His being a family of contractors;

including his grandfather, father, four

uncles and a brother; was up against the

idea of his choosing architecture as a

career option. His father had once asked

him “Why become an architect when

you can be a builder?”

Renzo Piano rejected his father‟s trade

and studied architecture at Milan

Polytechnic Architecture School.

During his studies he worked under the

design guidance of Neo-Rationalist

Franco Albini. After his graduation in 1964

Renzo Piano worked in his father's

company for a brief period, gaining

practical experience. During 1965-1970

Renzo Piano worked in offices of Louis I.

Kahn in Philadelphia and Z S Makowski in

London.

ea

rly li

fe

During his travels in America and London, he met Jean Pouvre, a French

metal worker and designer. His friendship with him is said to have deeply

influenced his professional life.

During this time, Piano moonlighted on his own projects, including a series

of temporary structures featuring steel space frames wrapped with

reinforced-polyester panels. These early pavilions reveal a number of

themes that run through almost all of his subsequent work: to minimize a

building‟s actual and apparent weight, an experimental approach to

materials, an obsession with inventive ways of connecting building

elements, and a knack for turning exposed, repetitive structure into

poetic form.

In the 1970s and early ‟80s, Piano continued to explore notions of mobility

in projects such as an experimental vehicle for Fiat, a mobile construction

unit for use in Senegal, and a travelling exhibition pavilion for IBM.

Piano‟s investigations in temporary architecture led to his first major

commission: the Italian Industry Pavilion at the Osaka Expo in 1970. A

tensile structure with a steel frame and reinforced-polyester panels, the

giant rectangular building conjured images of a high-tech circus tent. An

experiment in prefabrication, the building was shipped to Japan in 15

containers.

While still studying in Milan, Renzo Piano married Magda Arduino, a girl he

had known from school days in Genoa. They have three children- two

sons and a daughter.

wo

rks

The first significant assignment of Piano was in 1969 when

he had to designed the Italian pavilion at Expo‟70 in

Osaka, Japan. The event was important in a way, as he

met Richard Rogers who was impressed by the way

Renzo had planned the entire episode. Their liaison was

fruitful in the forthcoming events as both entered the

international competition for the Georges Pompidou

Centre . A controversial selection, Piano and Rogers‟s

design elicited howls of scorn from conservative critics

and defenders of ancient Paris.

They were both introduced to structural engineer Peter

Rice during the construction of Pompidou Centre.

As Piano tackled major commissions, such as the Menil

Collection in Houston (completed in 1986), San Nicola

Stadium in Bari, Italy (1987), and Kansai Airport in Osaka,

Japan (1994), Rice helped him integrate structure and

form in each project.

His other works include the Fiat Lingotto Factory

renovation, and the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center

in New Caledonia in the ‟90s; and the Rome Auditoria,

the Nasher Sculpture Center, the Beyeler Foundation,

Berlin‟s Potsdamer Platz, the Zentrum Paul Klee, and the

Padre Pio Pilgrimage Church in the 21st century.

His ability to tame the enormous scale of Kansai and

Lingotto, to express the spirit of the indigenous Kanak

culture using a thoroughly modern vocabulary in New

Caledonia, and to create exquisite spaces for viewing

art at the Nasher and Beyeler demonstrated the range

of his talents. Throughout this period, Piano never

developed a signature “style,” but the fusion of

engineering with architecture became a guiding

principle shaping all of his work. Another force driving his

work was a collaborative design process that turned

various consultants, fabricators, and contractors into

essential team members. As a result, each of Piano‟s

buildings looked different, shaped by different hands

and responding to different sets of user needs and local

contexts.

Piano‟s sure hand with spaces for art, in particular those

at the Menil and Beyeler, has brought him a flood of

museum jobs in the U.S., including recently completed

buildings for the High in Atlanta, the Morgan Library in

New York City, and the Los Angeles County Museum of

Art (LACMA), as well as ongoing projects for the Kimbell

in Fort Worth, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Whitney in

New York City, the Isabella Stewart Gardner in Boston,

the Harvard University Art Museums in Cambridge,

Massachusetts, and the California Academy of Sciences

in San Francisco.

wo

rks

KANSAI INTL. AIRPORT TERMINAL, OSAKA, 1995

NEW YORK TIMES BUILDING, NY, 2007

CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES,

SAN FRANCISCO, 2008

MENIL COLLECTION,

HOUSTON 1987

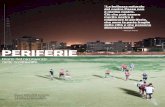

FOOTBALL STADIUM, BARI, 1990

NASHER SCULPTURE CENTRE,

DALLAS, 2003

CONTEMPORARY ART MUSEUM, LA, 2008

LINGOTTO FACTORY CONVERSION, TURIN, 2002

ATELIER BRANCUSSIPARIS, 1997

BEYELER FOUNDATION MUSEUM, RIEHEN, 1997

MORGAN LIBRARY,NY, 2006

the

ge

org

es

po

mp

ido

u c

en

tre

for

art

an

d c

ult

ure

, P

aris

(19

71

-19

77

)

The Pompidou Centre in English) is a complex in the Beaubourg area of

Paris. It was designed in the style of high-tech architecture.

It houses the Bibliotheque Publique d„Information, a vast public library,

the Musee National d'Art Moderne which is the largest museum for modern

art in Europe, and IRCAM, a centre for music and acoustic research.

The centre was designed by Renzo Piano and the British architect Richard

Rogers. Initially, all of the functional structural elements of the building were

colour-coded: green pipes are plumbing, blue ducts are for climate

control, electrical wires are encased in yellow, and circulation elements

and devices for safety(e.g. fire extinguishers) are red. However, this colour

coding has been partially removed, and many of the elements are simply

painted white.

All the functions of the building, including the walkways and the plant

systems, have been moved outside and are characterized to obtain a vast

and totally uncluttered space inside.

The centre with its ‟piazza‟ form a single moulded setting, actively providing

a resource of urban and social functions.

The building is a literally out of the box building. With all the services placed

along the skin of the building, it creates vast space inside for the visitors to

move around freely. But it is not the position of the services and structure

that draws attention but the very idea of „exposing‟ it, raises an eyebrow.

Now it may be a cult statement or a design feature to have services

exposed, but to think of such an idea at time, is unthinkable.

Paris and France have always been on the culture map of the globe. The

then French president wanted a place which becomes a new symbol for

Paris. Paris is over crowded with Romanesque and Gothic buildings and

those built during renaissance. All these buildings were being adapted as

museums to house the vast tangible and intangible culture of Paris, France

and the world in a more broader sense.

The centre, acts as a bold dot into the Paris landscape. The building stands

among the various buildings in and around Paris. One due to its iconoclast

expressionism in terms of the architecture style, sometimes classified as „hi-

tech‟ style, and two due to its bright colours, which attract attention.

It doesn't „fit‟ actually to its context, but marks the beginning of the new

context for Paris.

As an afterthought, the idea of having the services exposed on the facade

as well as on the ceiling, reduces the costs of wall finishes, annual repairs

and maintenance.

The turning the building inside out, too is an art. Its just not a decision to just

showcase the services and the structure to increase the movement space

within. It is more of an artistic expression. How the pipes will run along the

building, which colours to go with which one, the positions, their openings

etc are all a part of a well thought design.

The huge open space in front of the building, has become a major public

space for the Parisians. There are people of all age groups that collect in

the space during evenings. There are people giving stand up

performances etc.

The long escalator fitted in a tube acts a s major transition zone. A

transition from the open space outside to another open space inside, with

marked differences. In a zone where one would want to be open and look

out into the city, this tube does exactly the opposite.

To summarise about the building, it is in fact a bold opposite to the

prevailing architectural notions and thought processes. With extensive use

of steel and glass, it makes for a new architectural style for Paris. Though it

heralded a new era of design and construction style and technique, it still

remains one of its kind.

the

ge

org

es

po

mp

ido

u c

en

tre

for

art

an

d c

ult

ure

, P

aris

(19

71

-19

77

)

Located on the outskirts of the city of Bern,

Switzerland, the Zentrum Paul Klee, is a

multifunctional space. In addition to the

permanent collection, it also houses temporary

exhibitions, a concert hall, and a centre with

ateliers for children.

With the Alps as background, it is articulated

around three artificial hills: the central hill

containing the exhibition section, the north hill

housing a multifunctional room, the auditorium

and the children´s museum, and the south hill,

has been reserved for research and

management activities.

zen

tru

m p

au

l kle

e, b

ern

(1

99

9-2

00

5)

The majority of the works that form the

museum´s collection are not exhibited,

but are available to researchers. To ensure

the optimum preservation conditions, the

centre is illuminated from the west

façade, through which light is filtered by a

system of translucent screens, creating

softer light.

The undulating topography of the

adjoining hills inspired the profile of the

steel beams, which swoop and soar like a

rollercoaster, rising from the earth at the

rear to form a trio of imposing arches in

front.

Each rounded vault are linked at the front

by a 150m long glazed concourse

containing the cafe, ticketing, shop, and

reference area.

The structure, which intentionally remains

visible both from the inside and from the

outside, is formed by a series of parallel

steel arches. Steel was found to be only

material to provide an adequate

response to the largely different stresses,

as it allows variations in the plate

thicknesses without changing material

sections.

The 4.2km of steel girders were cut and shaped by computer-controlled

machines. The arches are slightly inclined at different angles, braced by

compression struts, and tied to the roof plate and floor slabs. In contrast, the

concrete floors were constructed as a single structure, without settlement joints.

The glass facade is divided into upper and lower sections, which are joined at

the 4m roof level of the concourse, and are suspended from girders to avert

stress from thermal expansion in the steel roof.

The glass is shaded by exterior mesh blinds that extend automatically in

response to the intensity of the light, and the high level of insulation minimizes

energy consumption.

Unlike the previous building discussed, the Zentrum Paul Klee has been

embedded in to the terrain with its gently undulating lines. The three hills made

of steel and glass mirror the topographical features on site and resume them in

such an organic manner that the building and its environment merge into a

"landscape sculpture".

Piano has tried to deal with the form first. With the serene landscape of the

Swiss Alps, he goes for an iconic building. In this building, there is this landmark-

first, function-second attitude. With an iconic shape, the functions of a museum

have been fitted inside the shape.

zen

tru

m p

au

l kle

e, b

ern

(1

99

9-2

00

5)

The functions seem to be out of place in the 3

diminishing arched shaped structures. The bigger of

three is the first attraction. But it houses the subsidiary

requirements such as the auditorium and the

cafeteria. The second arched building houses the

display. Maybe due to the shape, the display area is

an arrangement of partitions, as there are no walls in

the space.

The third built space houses the administration. The

medium hump leads to this space. There is no exit

from this space but to go through the gallery again.

The building in short suffices all the requirements of

context, form and elevation. But somewhere down

the line it fails to address the issue of function space as

a museum. Also the site has nothing to offer to the

visitors as landscaping or open outside space. Its just

the mountains that are there far away not as a part of

the site.

Renzo‟s work is a rare blending of the art, architecture and engineering with a

dash of intellectuality toped and garnished with classical Italian philosophy

and tradition.

The buildings of Renzo do not show stagnancy in any form of scale, material or

design rather his creations reflect the innovative mind of his matching with the

changing world. Piano follows the ancient code of the architect believing the

full command over the building process from design to the complete build

work. Off course such sensibility and awareness is expected from the

descendent of a family devoted to building profession.

His buildings are not just any tangible creation of bricks, stones, cement, iron

and asbestos but rather epitomes of creativity to the extent of being alive in its

own sense.

Renzo‟s list of creation includes homes to apartments, offices to shopping

centers, museums, factories, workshops and studios, airline and railway

terminals, expositions, theatres and churches, city planning, bridges, ships,

boats and cars. In other words, he hasn‟t limited himself to a particular

typology of buildings.

But sometimes a sense of repetition tends to reflect in his work. But this is

primarily due to the similar nature of programs. He says, “Making new shapes is

not difficult, but I don‟t believe in making up a new architecture every

Monday morning.”

Piano though modern in terms of his architecture, isn‟t too keen in using

modern software on computer. "But architecture is about thinking. It‟s about

slowness in some way. You need time to dream. The bad thing about

computers is that they make everything run very fast.“

He sees, however, a new architectural language developing for the 21st

century. “We understand now that the earth is fragile and our climate is

changing,” says Piano. “Our work needs to be anchored to this

understanding.” When he mentions recent projects, he invariably talks about

buildings that “breathe,” conserve resources, and use less energy.

Being one of the pioneers in „hi-tech‟ architect, and being called a

starchitect, Piano‟s buildings have started becoming more of an iconic

symbol than as a functional space.re

vie

w