Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

-

Upload

antonioferrante5318 -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

1/8

124

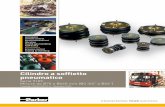

POSTHARVEST PHYSIOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGY OF CUT EUCALYPTUSBRANCHES: A REVIEW

S. Pacifici1, A. Ferrante2, A. Mensuali-Sodi1*, G. Serra1

1 Scuola Superiore S. Anna, Piazza Martiri della Libert 40, 56125 Pisa, Italy2 Dept. Produzione Vegetale, Universit degli Studi di Milano, Italy

SUMMARY - Cut Eucalyptusbranches are important ornamental filler used in bouquet and floral deco-rations. Italy is at the first place as country production for cut foliage export in Europe and one of thefirst in the world wide. Floriculture industry must be very competitive and quality must be guaranteedfrom the growth to the end-user. In floriculture, marketing and product distribution are critical issuesfor all countries. The production area and selling markets may be very far from each others with long

transportation periods. The storage and packaging systems play an important role for preserving qualityand reducing transportation costs. In this review the postharvest physiology of cut eucalyptus branchesare reported. Especially ethylene and respiration pattern such as the pulse treatments that can be usefulfor preserving quality.

Key words: cut foliage, eucalyptus, ethylene, storage, packaging, vase life

INTRODUCTION

Cut greens are an important component ofthe floricultural industry, largely used fordecoration as filler in floral compositions.They provide freshness and colour varietyto arrangements and bouquets. Cut euca-lyptus species are especially important forpreparing arrangements of flowers that arenaturally without leaves, such as gerberasand orchids. In many countries of the northEurope, in particular the UK, cut greens canbe used for indoor decorations during win-

ter time, providing a striking contrast to thewintry outdoor landscape.The increase of economic importance of cutfoliage production in the Italian ornamentalindustry is a result of the reorganizationof the internal production in response to acrisis period in the cut flower production.Word wide flower market has been becom-ing stronger and stronger for the flowerscoming from the developing countries such

as Colombia, Kenya etc., which can produceflowers at lower costs. Moreover, the glo- balization of the flower market led Italiangrowers to seek for alternative crops such ascut foliage. In addition, consumers are pay-ing more attention to the appearance of flo-ral compositions and foliage is now almostas important design element as the flowersthemselves.The Italian area for cut foliage productionwas 1542 ha in 2005, with a total productionof 1.3 million units with 85% of this culti-vation realized in plain area, and regionsprincipally involved were Liguria (58%),Campania (8.56%) and Tuscany (6.34%)(ISTAT, 2009). Data ISMEA-ISTAT reportedthat Italy in the 2006 imported 15% andexported 85% (on the economic value basis)cut foliage (Barsotto et al., 2008). Cut greensinclude many ornamental species and themost important are:Asparagus spp., Eucalyp-tus spp., Ruscus spp.,Hedera spp., Polypodiumspp. (ISTAT, 2006).

Agr. Med. Vol. 137, 124-131 (2007)

*Corresponding author. Tel. +39050/2216512; Fax: +39050/2216524; E-mail: [email protected]

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

2/8

125

S. PACIFICI, A. FERRANTE, A. MENSUALI-SODI, G. SERRA

BOTANY

Eucalyptus belongs to Myrtaceae family andis native of the Australia and Tasmania. The

most important species used for cut foliageproduction are: E. polverulenta (cv. Babyblue), E. cinerea, E. gunnii, E. nicholii, E. parvi-folia, E. perriniana, E. pupulifolia and E. stuar-tiana. These ornamental trees are also popu-lar for gum and essential oils productionthat can be extracted from leaves. Eucalyptusgrows in mild, warm and tropical climates,but cannot live at temperatures lower than-5C. In the recent years the cultivation areaof eucalyptus for cut branches production is

growing up. The plant is characterized byheterophylly that means the changing of leafshape during development. Young leavesare sessile and rounded shaped, while theold leaves are provided of peduncles andhave low ornamental value. Eucalyptus is amonoic plant with wind pollination and un-dergoes easily hybridization. Different spe-cies of eucalyptus are characterized by goodadaptability to different soils and climaticconditions, high productivity, good longev-

ity and stem resprouting.

PRODUCTION AND HARVEST

Eucalyptus species are cultivated in Mediter-ranean area and grow until 350 meters overthe sea level. Usually the young plants areplanted in spring or at the end of summer.Eucalyptus should be grown in climate withhigh humidity otherwise suffers of leaf bor-

der burning. It can grow in wide range ofsoils and with limited water supply. The soiloptimum pH ranges from 5.5 to 6.5.The yield of cut foliage varied from 2.87to 4.79 kg plant-1 (Forrest, 2002). Advisableplanting density for other eucalyptus speciesare:1-1.5 plant m-2 in E. cinerea and E. stuar-tiana, 1 plant m-2 in E. populifolia.Eucalyptus foliage can be harvested all yeararound with lower production in summer(August). The harvest begins on the lower

branches that should be harvested to 40-

60 cm long. Cut branches can be harvestedin immature (apical leaves are not com-pletely expanded) or mature stage (leaf fullyexpanded without soft tips). For commer-

cialization the leaves of cut foliage mustbe free of spots and injuries (mechanical orpathogen damages). Branches are groupedin 10 bunches for transport and marketing.The weight of each bunch usually rangesfrom 250 to 500 g. Harvesting time has animportant influence on postharvest waterlosses. Usually, harvesting should be done inthe morning when the temperature is coolerand the transpiration and metabolism of thefoliage are slowed down. Seasonal changing

and the harvest period in the year affect thevase life of eucalyptus branches: cut foliagesharvested in summer show shorter vase lifethan those collected in winter (Ferrante etal., 2000).The maturity stage of branches, at the har-vesting time, strongly affects the vase life.Environmental conditions during the differ-ent developmental stages also influence theleaf metabolism, in particular transpiration,respiration end ethylene production (Fer-

rante et al., 1998).The immature compared with maturebranches are more sensitive to water stressand during vase life show apical bending,while the mature branches mainly show leafdesiccation (Ferrante et al., 1998). In Table 1is reported vase life of different eucalyptusspecies.

POST-HARVEST PHYSIOLOGY

AND TECHNOLOGY

The vase life of the most part of cut euca-lyptus species is often satisfactory and doesnot need to be extended (Wirthensohn et al.,1996). However, there are some species thatmay get beneficial effects from treatmentswith preserving solutions, especially duringsummer periods such as E. parvifolia and E.gunnii (Ferrante et al., 1998). The vase lifeof E.parvifolia during May-June is below

10 days (Ferrante et al., 2000).

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

3/8

126

AGRICOLTURA MEDITERRANEA

Cut eucalyptus branches,such as other cut foliage, dur-ing postharvest life undergomany physiological changes

that may induce several dis-orders leading them to die.The senescence studies car-ried out on cut flowers andfoliage have greatly helpedto find technological strate-gies to prolong vase life ofcut eucalyptus foliage. Thequality and the vase life ofcut eucalyptus foliage essen-tially depend from the leaf

health status. Senescencesymptoms of cut eucalyp-tus foliage can be leaf wilt-ing, desiccation, rolling andnecrosis.However, the postharvestlife of cut eucalyptus foliagedepends from many internaland external factors, whichmay act synergistically re-ducing the vase life. There-

fore it is difficult to identifythe major physiological dis-order that limits the post-harvest life.The intensity of leaf colour is closely correlat-ed with the quality of ornamental cut foliage.The concentration of chlorophyll is directlycorrelated with consumers attractiveness.In the floriculture industry the use of chloro-phyll meter may be useful for estimating thequality of cut greens. Comparison studies

on chlorophyll measurements in E. parvifoliawere performed using no invasive method(SPAD) or analytical determinations (Pacificiet al., 2008b). Results were not satisfactoryand for this species SPAD values are not anindicator of leaf senescence.Cut foliage show chlorophyll degradationwhen they are already senescent, thereforethe chlorophyll content cannot be used asmarker for evaluating the quality of cut E.parvifolia branches (Ferrante et al., 2002b; Fer-

rante et al., 2003a,b; Pacifici et al., 2008a,b).

The main postharvest problem of cut euca-lyptus is the weight loss (during storage andtransportation) and reduced water uptake(during vase life). Since the cut eucalyptussuch as all cut greens are sold by weightand any reduction is directly translated ineconomic losses.

Among eucalyptus species there are E.youngiana and E.tetragona that are grown forcut flowering branches production and theflower life is the vase life-limiting factor (De-laporte et al., 2000; Delaporte et al., 2005).

Respiration, ethylene production and sensitivity

Cut branches after harvest continue to liveand all metabolic processes rapidly decline

if not correctly handled. Respiration of eu-

Table 1. Vase life (days) of Eucalyptus spp in different temperatureenvironment.

Species Vase life Literature

E. aggregata 35-40 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. albida 13-14 Wirthensohn et al., 1996E. cinerea 14-30 Wirthensohn et al., 1996;

Ferrante et al., 1998

E. ciccifera 35-40 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. cordata 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. crenulata 9-10 Jones et al., 1993

E. dalrympleana 31-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. globulus 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. gunnii 15-34 Ferrante et al., 2005

E. leucoxylon 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. linearis 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. maidenii 40-45 Bazzocchi et al., 1987E. nicholii 35-40 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. ovata 35-40 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. paniculata 35-40 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. parvifolia 13-31 Ferrante et al., 2000; 2002b;2005; Pacifici et al., 2008b

E. perriniana 35-40 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. polyanthemos 40-50 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. populnea 35-40 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. polverulenta 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. robusta 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. sideroxylon 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987E. stuartiana 30-35 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

E. urnigera 40-45 Bazzocchi et al., 1987

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

4/8

127

S. PACIFICI, A. FERRANTE, A. MENSUALI-SODI, G. SERRA

calyptus cut branches kept at 20C increaseup to three days of vase life with a rate thatranges from 2.5 to 10 mol CO2 h

-1 g-1 FW thanslightly decreased (Ferrante et al., 2003b).

The ethylene is another important parameterthat may affect the vase life of many cut flow-ers and foliage. The ethylene production of cuteucalyptus varies with the stage of leaf matu-rity. Cut immature branches have higher eth-ylene production compared to mature branch-es. In cut Eucalyptusparvifolia, the immature branches produce 6 nl h-1 g-1 FW (after 24 hin vase), while the mature branches producehalf amount of ethylene about 3 nl h-1 g-1 FW.Analogous results were found in immature

and mature branches of E.gunnii (Ferrante etal., 1998). However, ethylene production var-ies also from species to species. In cut E. gunniibranches the amount of ethylene ranges from4 to 11 nl h-1 g-1 FW during the first 24 hoursafter harvest (Jones et al., 1993; Ferrante et al.,1998), while the ethylene production in E.cin-erea ranges from 2-3 nl h-1 g-1 FW.Cut eucalyptus species can be consideredethylene insensitive, because exogenous ap-plications of ethylene induced visible dam-

age at 20 L L-1, reducing the vase life by19% compared to control. Since the ethyleneconcentration during the distribution chainor at retailer markets does not overcome 3 LL-1 the cut eucalyptus foliage can be reason-ably considered ethylene insensitive.Different behaviour was observed when cuteucalyptus was treated with 1 mM 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) theethylene precursor. Treatment ACC stronglyreduced the vase life and induced complete

leaf abscission (Ferrante et al., 2002a).Ethylene production and respiration trendswere opposite during vase life and eucalyp-tus cannot be ascribed to climateric or noclimateric pattern (Ferrante et al., 2003b).

Storage and packaging conditions

Environmental conditions during storageand transportation are extremely importantfor preserving quality of ornamental per-

ishables. Floriculture items have to be oftentransported for long distances before theyreach the selling markets and are highlysusceptible to quality losses. The packaging

systems play an important role in preventingwater losses, product damage and reducingtransportation costs.The optimal environmental conditions forcut foliage are low temperatures and highrelative humidity in order to minimize wa-ter losses. Temperature should be as low aspossible considering the freezing point ofspecies. However, the common storage andtransportation temperature ranges from 0to 5C. Low temperatures reduce all physi-

ological processes, especially respiration andethylene production. Temperatures close to0C should be preferred for long shippingdistance, while higher temperatures around5C may be used for local commercialization(Reid and Ferrante, 2002).Dry storage is not advisable in these spe-cies, because the high transpiration surfaceof cut foliage induces a rapid water loss andsubsequent wilting (Ferrante et al., 2002b).Recent studies on E. parvifolia showed that cut

branches can be dry stored if sealed in plastic bags and kept at 4C (Pacifici et al., 2008a,2008b). Optimal results were obtained whena mild vacuum was applied to sealed bagsreducing volume. In these experiments theair inside the bags was reduced but not com-pletely removed. Cut eucalyptus branchesdry stored in plastic bags under mild vacuumsatisfactory can be stored until 6 days withoutany negative effect on subsequent vase life(Pacifici et al., 2008b). This period of time may be enough for the most common transportdestinations. The maximum vacuum stor-age duration depends from the developmentstages at harvest of E. parvifolia. In fact, im-mature cut branches can be stored only for3 days (Pacifici et al., 2008a).Vacuum storage is a common practise forpreserving vegetables and fruits. In vac-uum storage bags or in storage chambersequipped with controlled atmosphere thegas concentration continuously changes, dueto plant tissue respiration generating a pas-

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

5/8

128

AGRICOLTURA MEDITERRANEA

sive modified atmosphere (Knee and Ag-garwal, 2000).The most important advantage of vacuumpackaging applied to the cut foliage industry

is the increase of loading capacity per unitof volume, reducing the transportation costswithout compromising the produce quality.Wet storage of cut foliage, instead, is themost used method at the selling point or infarm before transportation. Cut E.gunnii wassatisfactory stored for 4 weeks (Forrest, 1991)and cut E.parvifolia for 4 weeks (Ferrante etal., 2002b), without affecting the postharvestlife (Tab. 2). The effect of different storageconditions on the vase life of E. parvifolia is

reported in Tab. 2.

Water stress and postharvest treatments

The water stress may be a major problemfor several cut foliage. The water stress isoften caused by xylem occlusion, which may

be induced by bacterial growth in the vasewater (van Doorn, 1997). Weight losses ofcut foliage may be avoided using chemicalsthat improve the hydraulic conductance or

reducing the leaf transpiration in vase bytreatments with surfactants and weak acids.During transportation the pulse treatmentsshould be addressed to reduce water losseslimiting transpiration.Many treatments have been used for im-proving the vase life of cut eucalyptus spe-cies (Tab. 3). The compounds tested are thesame of those used for preserving cut flow-ers, which were studied alone or in combina-tions (i.e. Forrest, 1991; Wirthensohn et al.,

1996; Ferrante et al., 2002a). The commercialpreservative solutions recommended for cutfoliage are a mix of several chemical com-pounds and most of them are not declaimedfor patent reasons.Sugar: it is usually used in commercial for-mulations and is a source of food/energy for

Table 2. Effect of different postharvest environment conditions on the vase life (days) of E. parvifolia.

Storage TC Time storage Vase life Literature

Cold wet 5C 4 weeks 12.51.60 Ferrante et al., 2002b

Forrest 1991.Cold dry 5C 2 weeks 2.0 Ferrante et al., 2002b

Cold wet 4C 6 days 12.00.60 Pacifici et al., 2008a

Mild cold vacuum(dry storage)

4C 6 days 11.20.60 Pacifici et al., 2008a

Room temperature 14C day 10C night - 21.52.20 Ferrante et al.,2005

Room temperature 20C - 14.00.66 Pacifici et al., 2008aFerrante et al., 2002b

Table 3. Postharvest treatments to extend cut Eucalyptus spp. vase life (% of the control).

Treatments Concentrations Species Vase life Literature

AOA 1 mM E. parvifolia 5 Ferrante et al., 2002a

Cobalt chloride 2 mM E. parvifolia 30 Ferrante et al., 2002a

Glycerol 1 mM20%

E. parvifoliaE. cinerea

53n.d.

Ferrante et al., 2001Campell et al., 2000

Citric acid 150 mg L-1 E. parvifolia 56 Ferrante et al., 2001

Vaporgard 1% E. parvifolia 33 Ferrante et al., 2001

Sucrose + 8-HQS 10-20 g L-1 suc.+200 mg L-18-HQS

E.cinereaE. globulus

2695

Wirthensohn et al., 1996

Sucrose + 8 HQC 20 g L-1 suc. + 200 mg L-18-HQC

E. gunnii 20 Forrest, 1991

STS 2 mM E. gunnii 16 Forrest, 1991

Triton X 0.01% E. parvifolia 0 unpublished

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

6/8

129

S. PACIFICI, A. FERRANTE, A. MENSUALI-SODI, G. SERRA

cut ornamentals, especially for cut flowers.The most used sugar for making preservativesolutions is the sucrose with concentrationsranging between 0.5 to 20%. The sugar must

be supplied with biocides in order to inhibit bacteria growth. The sugar loading can beapplied as pulse treatment (24-48 h) or ascontinuous treatments. Of course, the choiceof one or another depends at which stage ofthe distribution chain the postharvest treat-ment is required. Cut eucalyptus speciestreated with sucrose have given oppositeresults depending from the species. Combi-nations of sucrose and 8-hydroxyquinolinesulphate (8-HQS) improved the vase life in

E. globules and E. cinerea (Wirthensohn andSedgley, 1996). Positive effect was obtainedalso in E. gunnii treated with sucrose and 8-hydroxyquinoline citrate (8-HQC) (Forrest,1991). Applications of sucrose in combina-tions with amino-oxyacetic acid (AOA) or8-HQS were not able to extend the vase lifeof cut E. parvifolia, even if avoided the weightlosses and improved the water uptake (Fer-rante et al., 2003a). It has been found thathigh levels of sugars in leaf are the triggers

of senescence (Sheen, 1990). In fact, it is wellknown that supplying sucrose to the plantsleaves lose their primary function, sinceplants do not need to produce carbohydratesthrough photosynthesis and activate the leafsenescence for reducing transpiration (Reidand Ferrante, 2002).Ethylene inhibitors: treatments applied tocut eucalyptus species did not always sat-isfactory extend the vase life. The AOAslightly improve the vase life, while thecobalt chloride has been more efficient to ex-tend the longevity of E. parvifolia cut foliage.Treatments with ethylene inhibitors wereable to inhibit the ethylene production (Fer-rante et al., 2002a).Treatments with silver thiosulphate (STS)did not increase the vase life of cut E. gunniibranches (Forrest, 1991).Biocides: they should be applied for reduc-ing the number of bacteria in the vase water.Bacteria are the most important factors thatlimit the vase life of cut flowers (Aarts, 1957).

Positive correlation has been found betweenbacteria obstruction and vessels occlusion incut ferns ofAdiantum raddianum (van Doornet al., 1991).

The ammonium quaternary salts (benzalko-nium chloride) did not give any beneficialeffect on vase life of E. cinerea, E. gunnii and E.parvifolia (Ferrante et al., 1998). These chemicalcompouds applied as pulse treatment for 48 hdecreased the vase life and the leaf quality.The sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) is a com-monly used biocide in water solution for cutflowers, unfortunately it was phytotoxic for E.parvifolia (data unpublished). On the contrary,pulse treatments with citric acid were able to

improve the vase life of this species (Ferranteet al., 2001). The citric acid improves the vaselife because reduces the pH and inhibits thebacterial growth. In fact, pH values of hold-ing solution should range from 3 to 4. Thesevalues block the bacteria growth that may oc-clude vessels and inhibits water uptake.Surfactants: cut branches of E. parvifolia weretreated with 0.01% Triton X, a non ionic sur-factant, with the aim to facilitate the wateruptake through the stems. The results did

not show significant difference between thevase life of treated and untreated branches(unpublished data).Antitraspirants and osmoregulators: treat-ment with an anti-transpirant Vaporgardhas not significantly increased the vase life,reducing the water uptake by limiting theleaf transpiration (Ferrante et al., 2001) of cutE. parvifolia branches. Anti-transpirants cre-ate a thin plastic film over the leaves avoid-ing the water losses through the stomata.Unfortunately, this treatment makes the cutbranches sticky and unmarketable.Cut foliage of E. parvifolia treated with glyc-erol showed longer life compared with con-trol (Ferrante et al., 2001). Analogous resultswere found in E. cinerea (Campbell et al.,2000). The glycerol induced a strong waterstress at beginning of experiment inducingan increment of ethylene production (Fer-rante et al., 2001). Glycerol absorbed by cellsincreases the water potential into leaves cre-ating a new water flux along the stem.

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

7/8

130

AGRICOLTURA MEDITERRANEA

CONCLUSIONS

The quality of cut foliage can be guaranteedby harvesting the eucalyptus branches at the

mature stage and during the coolest periodof the day such as early in the morning,especially in spring-summer time. Posthar-vest treatments are only required for cutfoliage that will be stored for long time orshipped for long distance and can be ap-plied before or after storage/transportation.These treatments should be performed withchemical compounds that improve wateruptake or reduce transpiration for avoidingthe cut branches weight losses. Transporta-

tion should be performed dry in plastic bagsassociated with a mild vacuum. Storage can be performed in water or in sealed plastic bags. The vase water at retailers should beacidized to 3-4 pH using weak acids such ascitric acid.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by funds of MIPAAF,

FLORPRO project 2006-2008 Individuazionedi tecniche di produzione, di conservazione ecommercializzazione, finalizzate alla riduzionedellimpatto ambientale e allottimizzazionedella qualit merceologica del prodotto. Pub-lication n 9

REFERENCES

AARTS J.F.T. (1957) On the keepability of cut flow-

ers meded. Landbouwhogesch. 57(9), 1-62.BARSOTTO P., STURLA A., TRIONE S. (2008) La

floricoltura ligure: un analisi del settore del con-

testo attraverso la RICA. INEA pp. 113.

CAMPBELL S.J., OGLE H. J. JOYCE, D.C. (2000)

Glycerol uptake preserves cut juvenile foliage of

Eucalyptus cinerea. Australian Journal of Experi-

mental Agriculture. 40(3), 483-492.

DELAPORTE K.L., KLIEBER A., SEDGLEY M. (2000)

Postharvest vase life of two flowering Eucalyptus

species. Postarvest Biology and Tesnology 19,

181-186.

DELAPORTE K.L., KLIEBER A., SEDGLEY M. (2005) Effect of sucrose at different concentrations and

cold dry storage on vase-life of three ornamental

Eucalyptus species. Journal of Horticultural Sci-ence & Biotechnology 80(4), 471-475.

FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G., TO-

GNONI F. (1998) Ethylene production and vase

life in cut Eucalyptus spp. foliage. Italus Hortus.5(5/6), 57-60.

FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G.,

TOGNONI F. (2000) Seasonal effects on vase

life of cut Eucalyptusparvifolia Cambage. Colture

Protette. 29(7), 79-83.

FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G.,

TOGNONI F. (2001) Consumo idrico, contenutiin clorofilla e durata in vaso di fronde recise di

Eucalyptus parvifolia Cambage. Giornata di Studio

sulle Fronde Verdi Recise. Santa Flavia 4 maggio

2001 PA, ACE International Flortecnica, suppl. 5,

197-203.

FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G.,

TOGNONI F. (2002a) Effects of ethylene and

cytokinins on vase life of cut Eucalyptusparvifolia

Cambage branches. Plant Growth Regulation.

38(2), 119-125.

FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G., TO-GNONI F. (2002b) Effects of cold storage on vase

life of cut Eucalyptusparvifolia Cambage branches.

Agricoltura Mediterranea.. 132(2), 98-103.

FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G.,

TOGNONI F. (2003a) Effetto del saccarosio sulla

durata postraccolta delle fronde recise di eucal-

ipto. Italus Hortus 10, 43-48.FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G.,

TOGNONI F. (2003b) Studio della senescenza

fogliare in fronde recise di Eucalyptus spp. Italus

Hort. Vol. 10, 24-28.FERRANTE A., MENSUALI-SODI A., SERRA G., TO-

GNONI F., (2005) Valutazione della longevit di

fronde recise di Eucalyptusgunnii J.T. Hook e di E.

parvifolia Cambage. Colture protette, 2, 85-89.

FORREST M. (1991) Post-harvest treatments of cut

foliage. Acta Horticulturae 298, 255-261.

FORREST M. (2002) The performance of a Euca-lyptus gunnii cut foliage plantation over 7 years.

Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research41, 235-245.

ISTAT (2006): Statistiche dellagricoltura anni 2001-2002. Annuario, n. 49 2006.

ISTAT (2009) Dati annuali sulla floricoltura. In ht-

tp://www.istat.it/agricoltura/datiagri/fiori/.

JONES R.B., TRUETT J.K., HILL M. (1993) Posthar-

vest handling of cut immature Eucalyptus foliage.

Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture

33, 663-667.

KNEE M. AND AGGARWAL D. (2000) Evalua-

tion of vacuum containers for consumer storage

of fruits and vegetables. Postarvest Biology and

Technology 19, 55-60.

-

8/9/2019 Postarvest handling eucalyptus AgrMed2007

8/8

131

S. PACIFICI, A. FERRANTE, A. MENSUALI-SODI, G. SERRA

PACIFICI S., MENSUALI-SODI A., FERRANTE A.,

SERRA G. (2008a) Comparison between conven-tional and vacuum storage system in cut foliage.

Acta Horticulture, 801, 1197-1203.

PACIFICI S., MENSUALI-SODI A., FERRANTE

A., TOGNONI F., SERRA G. (2008b) Fronderecise di eucalipto leffetto della conservazione

convenzionale e sottovuoto. Colture Protette 9,

112-120.

REID M. AND FERRANTE A. (2002) Conservazi-

one di fiori e fronde recise. Ed. ARSIA Regione

Toscana.

SHEEN J. (1990) Metabolic repression of transcrip-

tion in higher plants. The Plant Cell. 2, 1027-1038.VAN DOORN W.G., ZAGORY D., REID M.S. (1991)

Role of ethylene and bacteria in vascular Blokage

of cut fronds from the fern Adianthum raddianum.

Scientia Hort. 46, 161-169.VAN DOORN W.G. (1997) Water relations of cut

flowers. Horticultural Rev. 18, 1-85.

WIRTHENSOHN M.G., SEDGLEY M., EHMER R.

(1996) Production and postharvest treatment

of cut stems of Eucalyptus L. Hr. Foliage. Hort-

Science 31(6), 911-915.