SENSITIVE INVERTEBRATE PROFILE · Web viewnumerous searches for this species have occurred in...

Transcript of SENSITIVE INVERTEBRATE PROFILE · Web viewnumerous searches for this species have occurred in...

SPECIES FACT SHEETScientific Name: Plebejus saepiolus littoralis J. Emmel, T. Emmel, and Mattoon in T. Emmel, 1998Common Name: Coastal Greenish BluePhylum: ArthropodaClass: InsectaOrder: LepidopteraFamily: Lycaenidae(ITIS 2016)

Synonyms: Icaricia saepiolus littoralis (Pelham 2016), Plebjus saepiolus nr. insulanus (Miller & Hammond 2007).

Type Locality: California: Del Norte County; sand dunes at west end of Kellogg Road, north end of Lake Earl, 2 miles west of Fort Dick, elevation 25’ (Emmel et al. 1998).Conservation Status:

Global Status: G5T1T3 (last reviewed 1 June 1999)National Status (United States): N1N3 (1 June 1999)State Status: S1 – Critically imperiled (Oregon)(NatureServe 2015)Federal Status: Species of Concern (ORBIC 2016)ODFW Status: Conservation Strategy Species (ORBIC 2016)IUCN Red List: Not assessed (IUCN 2016)

Taxonomic Notes:

The nominate species, Plebejus saepiolus, is a common and widespread butterfly found across montane North America. At least 12 subspecies have been identified based on differences in wing pattern morphology, regional isolation, or both (Weyland 2013, ITIS 2016). While some genetic and morphological analyses have recently been conducted to support these subspecies designations (see Weyland 2013), questions about the distribution and taxonomy of Pacific Northwest coastal P. saepiolus populations remain.

Two subspecies have been described from the Pacific Northwest coast: P. s. insulanus and P. s. littoralis. Canadian lepidopterists recognize the P. s. insulanus subspecies as a separate subspecies confined to southeastern Vancouver Island (Layberry et al. 1998, COSEWIC 2000, Guppy & Shepard

1

2001, GOERT 2003). In the United States, Scott (1986) shows the subspecies P. s. insulanus as being more widespread and having a range from northwestern California to southwestern B.C. (Vancouver Island only), Montana, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. Hinchliff (1994) applies P. s. insulanus to a few isolated populations that occur only on the immediate Oregon coast. Warren (2005) refers to the central Oregon coast (“north coastal”) populations as P. s. nr. insulanus and the south coastal ones as P. s. littoralis, noting that the north coastal populations are phenotypically similar to P. s. insulanus. Ross (2017, pers. comm.) notes that collections from the Florence, OR, population appear to be more akin to the P. s. nr. insulanus phenotype than the topotypical P. s. littoralis further south. However, Hammond (2017, pers. comm.), in reviewing P. saepiolus specimens at the Oregon State Arthropod Collection, has not found any significant distinguishing characters between specimens identified as P. s. nr. insulanus and P. s. littoralis, and considers them synonyms.

Until the taxonomy of this coastal subspecies is sorted out, we follow Hammond’s (2017, pers. comm.) designations and treat P. s. nr. insulanus as a synonym of P. s. littoralis.

Technical Description:

Adult: This small butterfly is a member of the Lycaenidae family and Polyommatinae subfamily, the latter of which is commonly known as the blues. As the name suggests, these butterflies are characterized by their blue wing coloration, especially in the males. Females are typically gray or brown with blue highlights. Many species of blues exhibit orange crescents (aurorae) and shiny metallic rings (scintillae) along some of the dorsal and/or ventral wing edges, features which may sometimes be present in this subspecies.

P. s. littoralis adults are slightly larger than other subspecies in this group and have reduced black spots below with unique white haloes (Emmel et al. 1998, Pyle 2002, Warren 2005). Individuals from southern coastal colonies may be darker blue and more heavily spotted than those found further north (Warren 2005, Pyle & LaBar, in press).

Immature: The immature stages of this subspecies have not been described. Other subspecies of P. saepiolus have sphere-shaped, greenish or bluish-white eggs and light green or reddish brown larvae (James & Nunnallee

2

2011). The larvae have two white lines along the side of the body, sometimes accompanied by tiny white and black spots (James & Nunnallee 2011).

Photographs of adult males and females are available in Appendix 4. James and Nunnallee (2011) provide species-level photographs of the eggs and each larval instar.

Similar species: A number of other blue butterflies occur along the Oregon coast that may be confused with this subspecies. The echo blue (Celastrina echo) and the silvery blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus) both have a single row of markings on the underside of the hindwings compared to the two rows found on the coastal greenish blue. The silvery blue is also more iridescent on the upperside of its wings and has a more regular row of round black spots on the underside of its hind wing (Opler 1999). The western tailed blue (Everes amyntula) has small tails on the edge of the hindwings. Boisduval’s blue (Icaricia icarioides) is larger than the coastal greenish blue but also has white spots or white-encircled black spots on undersides of its hind wings.

Life History:

Adults: According to Emmel et al. (1998), P. s. littoralis flies in a single brood from early May to mid-June. In Oregon, specimens have been collected from May 17 (2 miles north of Gold Beach) to June 16 (Bullard Beach State Park). Adults of the nominate species nectar on numerous flowering plants including clovers (Trifolium spp.), trefoil (Lotus spp.), bistort, chickweed, yarrow, purple thyme, and various composites (James & Nunnallee 2011; Pyle and LaBar, in press). Males visit mud and patrol near host plants, flying close to the ground and searching for females. Females lay their eggs singly on the seeds or petals of blooming clover flowers (including Trifolium monanthum, T. longipes, and T. wormskioldii) (Pyle 2002, James & Nunnallee 2011).

Larvae: Caterpillars of this subspecies are food plant specialists that feed on springbank clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) in coastal grasslands (Miller & Hammond 2007; Hammond 2017, pers. comm.). Unlike many other larvae in the blues group, greenish blue caterpillars do not appear to be myrmecophilous (ant-tended) (James & Nunnallee 2011). Larvae overwinter in vegetation or detritus at the base of their host plants (James & Nunnallee 2011).

3

Range, Distribution, and Abundance:

Range: The nominate species’ range extends throughout the western and northern United States and into Canada (Pyle 2002); however, little is known about the historic range of the subspecies P. s. littoralis (Miller & Hammond 2007). Populations likely once occurred on higher elevation headlands overlooking the Pacific Ocean from Oregon southward to northern California near Crescent City; several of these populations are now extinct (Miller & Hammond 2007, ORBIC 2017). The most extensive extant populations are found in wet meadows of open sand dunes at the type locality near Lake Earl in Del Norte County, CA (Miller & Hammond 2007).

Distribution: Historical data show the coastal subspecies present from Lake Earl, Del Norte Co., CA; 2 miles north of Gold Beach, Curry Co., OR; Cape Blanco, Coos Co., OR; Coquille River Lighthouse, Coos Co., OR; Rock-Big Creeks, Lane Co., OR; and De [Devils] Lake, Lincoln Co., OR (Hinchliff 1994, Emmel et al. 1998, Pyle 2002, Warren et al. 2012, ORBIC 2017). A single record from Clatsop County, OR, (near Elsie) may have been due to a mislabeled specimen (Warren 2005) or agricultural introduction (Pyle 2002) and has not been included in the distribution for this subspecies.

Populations of P. s. littoralis are now known only from small areas of the Coast Range ecoregion in Lane, Curry, and Coos Counties in Oregon and Del Norte County, California (Pyle 2002, Ross 2006, Davenport et al. 2007, Weyland 2013, Ross 2015, Ross 2016, pers. comm., GBIF 2017, Lyons 2017, pers. comm., ORBIC 2017).

BLM/Forest Service Land:

Documented: Plebejus saepiolus littoralis has been reported from two locations on the Siuslaw National Forest: between Rock and Big Creeks, in T16SR12W (Hinchliff 1994, Warren 2005, ORBIC 2017), and on the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area near Florence (Ross 2015).

Suspected: P. s. littoralis is suspected on the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Northwest Oregon BLM District, and Coos Bay BLM District based on proximity to known sites and availability of the known host plant (Trifolium wormskioldii; see Oregon Flora Project 2016).

Abundance: Abundance estimates for this subspecies across its range are not available. In 2009, 499 adults were estimated at the Bullard Beach State

4

Park site between May 25 and June 16, 2009, and 375 adults were estimated at the Cape Blanco State Park site (ORBIC 2017).

Habitat Associations:

Plebejus saepiolus is primarily found in cool mountain meadows wherever moist seeps and clovers occur together (James & Nunnallee 2011); the coastal subspecies is unusual in that it is found at lower elevations in sand dunes and salt spray meadows along the coast (Applegarth 1995, Weyland 2013, ODFW 2016). Conifer trees adjacent to meadows can serve as important shelter and windbreaks (ODFW 2016). Larvae depend on clovers, particularly springbank clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) (Pyle 2002, Warren 2005, James & Nunnallee 2011).

The P. s. littoralis type locality at the north edge of Pacific Shores in California is characterized by coastal terrace prairie and dune communities including native dune mat and invasive European beachgrass dominated areas (BCRAA 2013). The Tolowa Dunes State Park habitat is similarly described as a grassy coastal meadow (Lyons 2017, pers. comm.). Oregon specimens collected from the Coquille River Lighthouse were found in moist depressions on the lee side of sand dunes along the access road. At the Bullards Beach and Cape Blanco State Parks sites in Oregon, populations were associated with dune species including springbank clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) and invasive European beachgrass (Ammophila arenaria) and gorse (Ulex europaeus) (ORBIC 2017).

Threats:

Lycaenids as a group appear to have a high degree of subspecific variation and their differentiated populations are particularly susceptible to endangerment and extinction (Cushman & Murphy 1993). Butterflies with fragmented or isolated distributions such as P. s. littoralis are at a greater risk of local extinction from climate change or large disturbance events such as fire (Cornelissen 2011, Ehrlich and Hanski 2004, Oliver et al. 2015). The response of this particular subspecies to fire is unknown (Applegarth 1995); however, periodic ground fires set by Native Americans may have been important in maintaining coastal meadow habitats in the past (Miller &

5

Hammond 2007). In recent times, much of this meadow habitat has been lost due to human development and the loss of periodic fire, leading to succession of early seral plant communities (such as shore pine encroachment on open meadow sites) and competition by invasive plants, including gorse, European beachgrass, and Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) (Miller & Hammond 2007, ODFW 2016, ORBIC 2017).

Threats to the coastal greenish blue include human development, succession of moist meadow or dune habitat to shrub/woodland habitat, competition from invasive plants, trampling by humans, livestock or offroad vehicles, or other natural ecological factors (ORBIC 2017). Plebejus saepiolus requires clovers (Trifolium spp.) as its larval food plant (Pyle 200, Miller & Hammond 2007, James & Nunnallee 2011), which may limit the habitats in which it occurs. The coastal Oregon populations of native Trifolium are known to be affected by invasive plants (Shepard 2000), which also displace adult nectar sources (ODFW 2016). Some of these same threats have been documented for the seaside hoary elfin (Incisalia polia maritima) and the federally threatened Oregon silverspot (Speyeria zerene hippolyta), rare butterflies that are also confined to similar coastal habitats in Oregon.

Conservation Considerations:

Research: The taxonomy and subspecific boundaries of P. s. littoralis are currently in flux and should continue to be studied and revised. Further study of coastal Oregon populations of P. saepiolus is needed to determine their overall distribution and taxonomic status (Warren 2005). Improved understanding of P. saepiolus subspecies distributions will assist in identification of conservation priorities. Specimens or mtDNA sequences from material collected from coastal Oregon populations of Plebejus saepiolus are needed to complete genetic analyses that could be used to support taxonomic revisions. Due to the fragmented nature of populations of this subspecies, it may be important to determine minimum population size thresholds to inform management.

Inventory: Surveys can be used to more accurately determine the current distribution of the coastal greenish blue and to establish its local relative abundance and the threats to populations wherever they occur. Larval abundance could be assessed by sampling springbank clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) host plants with a sweep net or by conducting a visual search (Miller & Hammond 2007). Adults may be sampled by conducting timed

6

visual searches along transects through suitable habitat where nectar plants are present (Miller & Hammond 2007). Regular monitoring of the few extant populations in Oregon will further inform the status of this subspecies.

Historical sites could be visited first to determine the presence/absence of the butterfly there. Given the paucity of historical and current records for the taxon, searches for additional populations could also be conducted, although numerous searches for this species have occurred in recent years (Ross 2016, pers. comm.) and discovery of new populations may be unlikely. The North Spit Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) and New River ACEC (Coos Bay BLM) were extensively searched for this species by Ross (2006), particularly in low, moist, open areas with Trifolium or Lotus plants (the latter of which may be another host genus in Oregon). Ross (2006) believes it is unlikely that viable breeding populations of this subspecies occur at either site. However, it is possible that individuals from nearby colonies could stray to or even colonize appropriate habitat at these sites, although it is unknown if any nearby source populations exist (Ross 2006). Additional surveys on BLM and Forest Service lands (such as the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest) could target sand dunes and coastal salt spray meadows inhabited by this species’ known host plant, springbank clover (Trifolium wormskioldii).

Land managers could combine surveys of another Forest Service sensitive species, the seaside hoary elfin, with surveys for the coastal greenish blue, as they are known to use similar and overlapping habitats. However, the hoary elfin flies from March to mid-May (Ross 2006), whereas most records for the coastal greenish blue are from May and June (ORBIC 2017).

Data forms for Forest Service and BLM units to utilize during surveys can be found at http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/sfpnw/issssp/inventories/monitoring.shtml.

Management: Protect all potential and known sites of occurrence from practices that would adversely affect any aspect of this species’ life cycle or habitat, including tree encroachment on meadow habitat, ORV use, and other recreational pressures. Evaluate the impact of hikers and recreationalists on habitat and populations and manage these impacts to protect and maintain existing habitat. Survey known areas to determine if and where conifer encroachment or invasive species are negatively impacting larval habitat, and consider treatments to reduce shrub or tree encroachment if needed and promote larval and adult resources such as host

7

and nectar plants. Maintain some areas of conifer trees next to salt-spray meadows to act as windbreaks. Managers may need to consult with an expert in managing habitat for butterflies before moving forward on restoration projects or projects that may adversely impact the sites. Existing management activities such as mowing or applying herbicide to coastal meadows to control exotic grasses and woody plants must be carefully assessed to determine if these acts are benefiting or harming the coastal greenish blue. Prescribed fire might be helpful in keeping coastal meadows open, however Applegarth (1995) notes that an experimental fire intended to benefit the Oregon silverspot had the unexpected and detrimental effect of dense stands of bracken ferns, which could crowd out required nectar and host plants.

Version 2:Prepared by: Candace FallonThe Xerces Society for Invertebrate ConservationDate: June 2017

Reviewed by: Michele BlackburnThe Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

Version 1: Prepared by: Scott Hoffman Black, Logan Lauvray, and Dana RossThe Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation and Independent Lepidopterist, Corvallis, ORDate: September 2005ATTACHMENTS:

(1)References (2)List of pertinent or knowledgeable contacts (3)Maps of known records in Oregon(4)Photographs of this and related subspecies(5)Survey protocol, including specifics for this subspecies

ATTACHMENT 1: References

Applegarth, J.S. 1995. Invertebrates of special status or special concern in the Eugene District. Prepared for the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 126 pp.

[BCRAA] Border Coast Regional Airport Authority. 2013. Biological Assessment. Del Norte County Regional Airport, Jack McNamara Field (CEC).

8

Prepared for the Federal Aviation Administration. Available online at http://www.vanir.com/portals/0/delnorte/6_bcraa_biological_assessment_2013-02-25.pdf (accessed 12 December 2016).

Cornelissen, T. 2011. Climate change and its effects on terrestrial insects and herbivory patterns. Neotropical Entomology, 40(2), 155-163.

[COSEWIC] Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2000. Status report on Island Blue in Canada. Ottawa, ON. Available online at http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_bleu_insulaire_island_blue_2000_e.pdf (accessed 10 March 2017).

Cushman, J.H. and D.D. Murphy. 1993. Conservation of North American lycaenids – an overview. In: New, T.R., (ed.). Conservation Biology of Lycaenidae (Butterflies). IUCN, Switzerland. Available online at https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/SSC-OP-008.pdf (accessed 14 February 2017).

Davenport, K.E., R.E. Stanford, and R.L. Langston. 2007. Flight periods of California butterflies for "resident species", subspecies and most strays to the state. The International Lepidoptera Survey Newsletter 8(1). Available online http://lepsurvey.carolinanature.com/ttr/ttrnews-8-1.pdf (accessed 7 February 2017.)

Emmel, J.F, T.C. Emmel and S.O. Mattoon. 1998. New Polyommatinae Subspecies of Lycaenidae (Lepidoptera) from California. Pages 171-200 in T. C. Emmel, editor. Systematics of western North American butterflies. Mariposa Press, Gainesville, Florida. 878 pp.

Ehrlich, P.R., Hanski, I. 2004. On the Wings of Checkerspots: A Model System for Population Biology. Oxford University Press, New York. 371 pp.

[GBIF] Global Biodiversity Information Facility. 2017. Plebejus saepiolus subsp. littoralis. Available online at http://www.gbif.org/occurrence/search?TAXON_KEY=5714715&q=plebejus+saepiolus+subsp.+littoralis (Accessed 10 January 2017).

[GOERT] Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team. 2003. Species at risk in Garry oak and associated ecosystems in British Columbia. Gary Oak Ecosystem Recovery Team, Victoria, British Columbia. Available online: http://www.goert.ca/documents/SAR_manual/Plebejus_saepiolus.pdf (accessed 7 February 2017).

9

Guppy, C.S. and J.H. Shepard. 2001. Butterflies of British Columbia. University of B.C. Press, Vancouver, BC and Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria, BC.

Hammond, P. 2017. Personal communication with Candace Fallon, the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Lepidopterist, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. March 21.

Hinchliff, J. 1994. An atlas of Oregon butterflies. The Evergreen Aurelians. Oregon State University Bookstore, Corvallis, OR. 176 pp.

[ITIS] Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 2015. Plebejus saepiolus littoralis. Retrieved 6 December 2016 from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System on-line database, http://www.itis.gov.

[IUCN] International Union for the Conservation of Nature. 2016. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2016-3. <http://www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 7 February 2017.

James, D. and D. Nunnallee. 2011. Life histories of Cascadia butterflies. OSU Press, Corvallis, Oregon. 448 pp.

Layberry, R.A., P.W. Hall, and D.J. Lafontaine. 1998. The Butterflies of Canada. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, ON.

Lyons, R. 2017. Personal communication with Candace Fallon. Entomologist, Oregon Entomological Society. March 1.

Miller, J.C. and P.C. Hammond. 2007. Butterflies and moths of Pacific Northwest Forests and Woodlands: Rare, endangered, and management-sensitive species. 234 pp. Available online at https://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/pdfs/MILLER_LEPIDOPTERA_WEB.pdf (accessed 10 March 2017).

NatureServe. 2015. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://explorer.natureserve.org. (Accessed: December 6, 2016).

[ODFW] Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2016. Oregon Conservation Strategy. Available online at http://oregonconservationstrategy.org/ecoregion/coast-range/ (accessed 6 December 2016).

10

Oliver, T. H., Marshall, H. H., Morecroft, M. D., Brereton, T., Prudhomme, C., & Huntingford, C. 2015. Interacting effects of climate change and habitat fragmentation on drought-sensitive butterflies. Nature Climate Change, 5(10), 941-945.

Opler, P. 1999. A Field Guide to Western Butterflies. 2nd ed. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

[ORBIC] Oregon Biodiversity Information Center. 2016. Rare, threatened and endangered species of Oregon. Institute for Natural Resources, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. 130 pp. Available online at http://inr.oregonstate.edu/sites/inr.oregonstate.edu/files/2016-rte-book.pdf (accessed 14 February 2017).

[ORBIC] Oregon Biodiversity Information Center. 2017. Data system search for rare, threatened and endangered plants and animals. Requested by Candace Fallon for the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Records received 22 February 2017.

Oregon Flora Project. 2016. Online Oregon Plant Atlas website. Oregon State University, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology. Accessed 14 February 2017. Available at: http://oregonflora.org/atlas.php.

Pelham, J.P. 2016. A catalogue of the butterflies of the United States and Canada. Available online at http://butterfliesofamerica.com/US-Can-Cat.htm (accessed 14 February 2017).

Pyle, R.M. 2016. Candace Fallon’s personal communication with Bob Pyle. Biologist, writer, and independent scholar. 369 Loop Road, Gray's River, WA 98621. December 21.

Pyle, R.M. 2002. The Butterflies of Cascadia: A Field Guide to all the Species of Washington, Oregon, and Surrounding Territories. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle, Washington.

Pyle, R.M. and C.C. LaBar. In press. Butterflies of the Pacific Northwest. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

Ross, D. 2006. Surveys for seaside hoary elfin (Incisalia polia maritima) and insular blue butterfly (Plebejus saepiolus littoralis) at North Spit ACEC and New River ACEC. With summary by H.F. Witt and M.V. Heyden. Available

11

online at http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/sfpnw/issssp/documents/inventories/inv-rpt-iile-capom-and-plsal-coos-surveys-2006-08.pdf (accessed 6 December 2016).

Ross, D. 2015. 2015 surveys for coastal greenish blue and seaside hoary elfin butterflies on the Oregon Dunes NRA. A summary report to the Siuslaw National Forest. Available online at http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/sfpnw/issssp/documents4/inv-rpt-iile-coastal-butterflies-siu-2015.pdf (accessed 6 December 2016).

Ross, D. 2016. Candace Fallon’s personal communication with Dana Ross. Entomologist. 1005 NW 30th St. Corvallis, OR 97330. December 21.

Ross, D. 2017. Candace Fallon’s personal communication with Dana Ross. Entomologist. 1005 NW 30th St. Corvallis, OR 97330. February 28.

Scott, J.A. 1986. The butterflies of North America. Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, CA.

Shepard, J.H. 2000. Status of five butterflies and skippers in British Columbia. B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Wildlife Branch and Resource Inventory Branch, Victoria, BC. 27 pp. Available online at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.500.3579&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 7 February 2017).

Warren, A.D. 2005. Lepidoptera of North America 6, Butterflies of Oregon: Their Taxonomy, Distribution, and Biology. Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon.

Warren, A.D., K.J. Davis, N.V. Grishin, J.P. Pelham, E.M. Stangeland. 2012. Interactive Listing of American Butterflies. Available online at http://butterfliesofamerica.com/plebejus_saepiolus_littoralis.htm (accessed 10 January 2017).

Weyland, D.M. 2013. Phylogeography and diversification of the greenish blue butterfly (Plebejus saepiolus) in Western North America. Master’s Thesis: Texas State University-San Marcos. Available online at https://digital.library.txstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10877/4719/WEYLAND-THESIS-2013.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 12 December 2016).

ATTACHMENT 2: List of pertinent, knowledgeable contacts

Paul Hammond, retired, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR

12

David McCorkle, retired, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR

Robert M. Pyle, biologist, writer, and independent scholar, Grays River, WA

Dana Ross, contract entomologist, Corvallis, OR

Andrew Warren, Senior Collections Manager, McGuire Center for Lepidoptera & Biodiversity, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL

13

ATTACHMENT 3: Maps of known Plebejus saepiolus littoralis distribution

Known records of Plebejus saepiolus littoralis in southern Oregon and northern California, relative to Forest Service and BLM lands. Note that

14

specimens from Lincoln and Lane Counties have been identified as P. s. nr. insulanus, which we treat here as a synonym of P. s. littoralis.

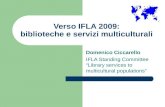

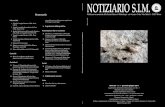

ATTACHMENT 4: Photographs of this and related subspecies

Figure 1: Plebejus saepiolus littoralis from Del Norte County, CA. From left: male dorsal, female dorsal, and mating pair (male on left, female on right). Photos by Ron Lyons (used with permission).

Figure 2: P. s. littoralis (identified by Ross [2016] as P. s. nr. insulanus) pinned specimen from Lane County, OR. Left: Male dorsal. Right: Male ventral. Specimen collected from the Florence, OR, population. Photos by Dana Ross (used with permission).

ATTACHMENT 5: Survey Protocol

Survey Protocol

By Sarah Foltz Jordan and Candace Fallon (last updated June 2016)Taxonomic group:

Lepidoptera

Where:

15

Lepidopterans utilize a diversity of terrestrial habitats. When surveying new areas, seek out places with adequate larval food plants, nectar sources, and habitat to sustain a population. Many species have highly specific larval feeding preferences (e.g. limited to one or a few related plant species whose defenses they have evolved to overcome), while other species exhibit more general feeding patterns, including representatives from multiple plant families in their diet. For species-specific dietary preferences and habitat information, see the section at the end of this protocol.

When:

Adults are surveyed in the spring, summer, and fall, within the window of the species’ documented flight period. Although some butterfly species overwinter as adults and live in the adult stage for several months to a year, the adult life spans of the species considered here are short and adults are available for only a brief period each year (see species-specific details, below). Larvae are surveyed during the time of year when the larvae are actively foraging on their host plants.

How to Survey:

Adults:

If possible, all sites should be surveyed for this butterfly during the following environmental conditions:

Minimum temperature: Above 60 degrees F.

Cloud cover: Partly sunny or better. On cooler days the sun can play a very important role in getting butterflies to take to the air. On warmer days (above 60 degrees F), direct sunlight is less important, but a significant amount of the sun’s energy should be coming through the clouds to help elevate the temperature of basking butterflies.

Wind: Less than 10 MPH. On windy days, butterflies will drop out of the air if they cannot maintain their direction and/or speed of flight.

Time of day: Between 10AM and 4PM. Success is most likely during the warmest parts of the day.

Time of year: Varies by region (see notes on flight period, below). If known, currently occupied sites should be checked before the start of the

16

planned survey period, as flight times may vary due to weather conditions in the spring and early summer.

Upon arriving at each potential site, the following survey protocol should be used:

Approach the site and scan for any butterfly activity, as well as suitable habitat. Butterflies are predominantly encountered nectaring at flowers, in flight, basking on a warm rock or the ground, or puddling (sipping water rich in mineral salts from a puddle, moist ground, or dung). Walk through the site slowly (about 100 meters per 5 minutes), looking back and forth on either side, approximately 20 to 30 feet out. Try to walk in a path such that you cover the entire site with this visual field, or at least all of the areas of suitable habitat. If you must leave the transect path (e.g., to look at a particular butterfly), do your best to return to the specific place where you left your path when you resume walking/searching through the site.

When a suspected target species is encountered, net the butterfly to confirm its identification. Adults are collected using a long-handled aerial sweep net with mesh light enough to see the specimen through the net. When stalking perched individuals, approach slowly from behind. When chasing, swing from behind and be prepared to pursue the insect. A good method is to stand to the side of a butterfly’s flight path and swing out as it passes. After capture, quickly flip the top of the net bag over to close the mouth and prevent the butterfly from escaping. Once netted, most insects tend to fly upward, so hold the mouth of the net downward and reach in from below when retrieving the butterfly.

Binoculars and cameras may also be used to view wing patterns of perched butterflies. Since most butterflies can be identified by macroscopic characters, high quality photographs will likely provide sufficient evidence of species occurrences at a site, and those of lesser quality may at least be valuable in directing further study to an area. Use a camera with good zoom or macro lens and focus on the aspects of the body that are the most critical to species determination (i.e. dorsal and ventral patterns of the wings) (Pyle 2002). When possible, take several photographs of potential target species showing a clear view of the underside and upperside of the wings at each survey area where they are observed.

17

If needed, the collection of voucher specimens should be limited to males from large populations. The captured butterfly should be placed into a glassine envelope. To remove the specimen from the net by hand, grasp it carefully through the net by the thorax with fingers or a pair of flat-nosed forceps, making sure the butterfly has its wings folded back. Place the specimen in an envelope and then into a small plastic container. Place the container in a cooler with ice, buffering the specimen from the ice with a towel. Transfer the container to a freezer to kill the animal.

If using a cyanide killing jar (Triplehorn & Johnson 2005), place the animal in the jar as soon as possible, pinching the thorax slightly to stun it, to avoid damage to the wings by fluttering. Small species, such as blues and hairstreaks, should not be pinched. Alternatively, the kill jar may be inserted into the net in order to get the specimen into the jar without direct handling, or spade-tip forceps may be used. Since damage to specimens often occurs in the kill jar, large, heavy-bodied specimens should be kept in separate jars from small, delicate ones, or killed by pinching and placed directly into glassine envelopes. If a kill jar is used, take care to ensure that it is of sufficient strength to kill the insects quickly and is not overcrowded with specimens. Following a sufficient period of time in the kill jar, specimens can be transferred to glassine-paper envelopes for storage until pinning and spreading. For illustrated instructions on the preparation and spreading of lepidopterans for formal collections, consult Chapter 35 of Triplehorn and Johnson (2005).

Fill out all of the site information on datasheet, including site name, survey date and time, elevation, aspect, legal location, latitude and longitude coordinates of site, weather conditions, and a thorough description of habitat, including vegetation types, vegetation canopy cover, suspected or documented host plant species, landscape contours (including direction and angle of slopes), degree of human impact, and insect behavior (e.g. “puddling”). Record the number of target species observed, as well as butterfly behavior, plant species used for nectaring or egg-laying, and survey notes. Photographs of habitat are also a good supplement for collected specimens and, if taken, should be cataloged and referred to on the insect labels. Collection labels should include the following information: date, time of day, collector, and detailed locality (including geographical coordinates, mileage from named location, elevation). Complete determination labels include the species name, sex (if known), determiner name, and date

18

determined. Mating pairs should be indicated as such and stored together, if possible. Record data for sites whether butterflies are seen or not. In this way, overall search effort is documented, in addition to new sites.

Relative abundance surveys can be achieved using either the Pollard Walk method, in which the recorder walks only along a precisely marked transect, or the checklist method, in which the recorder is free to wander at will in active search of productive habitats and nectar sites (Royer et al. 2008). A test of differences in effectiveness between these two methods at seven sites found that checklist searching produced significantly more butterfly detections per hour than Pollard walks at all sites, but the overall number of species detected per hour did not differ significantly between methods (Royer et al. 2008). The study concluded that checklist surveys are a more efficient means for initial surveys and generating species lists at a site, whereas the Pollard walk is more practical and statistically manageable for long-term monitoring. Recorded information should include start and end times, weather, species, sex, and behavior (e.g., “female nectaring on flowers of Trifolium wormskioldii”).

Immature:

Lepidoptera larvae are generally found on vegetation or soil, often creeping slowly along the substrate or feeding on foliage. Pupae occur in soil or adhering to twigs, bark, or vegetation. Since the larvae usually travel away from the host plant and pupate in the duff or soil, pupae of most species are almost impossible to find.

James and Nunnallee’s Life Histories of Cascadia Butterflies (2011) includes descriptions of many Lepidoptera species, providing important diagnostic information for identification of larval stages. For species or subspecies not covered in this book, rearing can be critical in both (1) enabling identification and (2) providing novel associations of larvae with adults (Miller 1995). Moreover, high quality (undamaged) adult specimens, particularly of the large-bodied species, are often best obtained by rearing.

Most species of butterflies can be easily reared from collected eggs, larvae, or pupae, or from eggs laid by gravid females in captivity. Large, muslin-covered jars may be used as breeding cages, or a larger cage can be made from boards and a fine-meshed wire screen (Dornfeld 1980). When collecting caterpillars for rearing indoors, collect only as many individuals as can be

19

successfully raised and supported without harm to the insect population or to local host plants (Miller 1995). A fresh supply of larval food plant will be needed, and sprigs should be replenished regularly and placed in wet sand rather than water (into which the larvae could drown) (Dornfeld 1980). The presence of slightly moistened peat moss can help maintain appropriate moisture conditions and also provide a retreat for the caterpillar at the time of pupation (Miller 1995). Depending on the species, soil or small sticks should also be provided as the caterpillars approach pupation. Although rearing indoors enables faster growth due to warmer temperatures, this method requires that appropriate food be consistently provided and problems with temperature, dehydration, fungal growth, starvation, cannibalism, and overcrowding are not uncommon (Miller 1995). Rearing caterpillars in cages in the field alleviates the need to provide food and appropriate environmental conditions, but may result in slower growth or missing specimens. Field rearing is usually conducted in “rearing sleeves,” which are bags of mesh material that are open at both ends and can be slipped over a branch or plant and secured at both ends. Upon emergence, all non-voucher specimens should be released back into the environment from which the larvae, eggs, or gravid female were obtained (Miller 1995).

According to Miller (1995), the simplest method for preserving caterpillar voucher specimens is as follows: Heat water to about 180°C. Without a thermometer, an appropriate temperature can be obtained by bringing the water to a boil and then letting it sit off the burner for a couple of minutes before putting the caterpillar in the water. Extremely hot water may cause the caterpillar to burst. After it has been in the hot water for three seconds, transfer the caterpillar to 70% ethyl alcohol (isopropyl alcohol is less desirable) for permanent storage. Note that since this preservation method will result in the caterpillar losing most or all of its color; photographic documentation of the caterpillar prior to preservation is important. See Peterson (1962) and Stehr (1987) for additional caterpillar preservation methods.

Species-Specific Survey Details:

Plebejus saepiolus littoralis

Plebejus saepiolus littoralis is known from a narrow band along the Oregon and northern California coasts in Lincoln, Lane, Coos, Curry, and Del Norte Counties. In addition to surveys for new sites, surveys to determine the

20

status of known populations are needed. Abundance estimates at known and new sites are also needed. Surveys at new sites could focus on appropriate habitat on the Siuslaw National Forest, Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Northwest Oregon BLM District, and Coos Bay BLM District.

This subspecies is known from sand dunes and coastal salt spray meadows with populations of its host plant, springbank clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) (Miller & Hammond 2007). Known sites along the Oregon and northern California coasts range in elevation from 3 to 122 m (10 to 400 ft.).

Surveys should take place during the adult flight period. Like other subspecies of P. saepiolus, this butterfly exhibits a single flight from May through June. Adults in this subfamily tend to stay in the vicinity of hostplants, nectaring abundantly in nearby meadows (Pyle 2002). The males gather in great numbers at mud-puddles (Pyle 2002) and patrol near the host plants for females (Scott 1986, James & Nunnallee 2011). Specific nectaring plants have not been reported for this subspecies; other subspecies nectar on numerous flowering plants including clovers (Trifolium spp.), trefoil (Lotus spp.), bistort, chickweed, yarrow, purple thyme, and various composites (Pyle 2002).

Plebejus saepiolus littoralis can be identified using wing characteristics, as outlined in the Species Fact Sheet, and location, as no other subspecies of P. saepiolus is currently known to occur along the Oregon coast; however, final determination is best done by a trained lepidopterist.

Surveys for P. s. littoralis could be coupled with surveys for the seaside hoary elfin (Incisalia polia maritima), another Forest Service sensitive species known from many of the same sites along the Oregon coast, and with a similar, albeit earlier, flight period (March to mid-May).

References (survey protocol only):

Dornfeld, E.J. 1980. The Butterflies of Oregon. Timber Press, Forest Grove, Oregon. 276 pp.

James, D. and D. Nunnallee. 2011. Life histories of Cascadia butterflies. OSU Press, Corvallis, Oregon. 448 pp.

Miller, J.C. 1995. Caterpillars of Pacific Northwest Forests and Woodlands. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, National Center of Forest Health Management, Morgantown, West Virginia. FHM-NC-06-95. 80 pp.

21

Miller, J.C. and P.C. Hammond. 2007. Butterflies and moths of Pacific Northwest Forests and Woodlands: Rare, endangered, and management-sensitive species. 234 pp. Available online at https://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/pdfs/MILLER_LEPIDOPTERA_WEB.pdf (accessed 10 March 2017).

Peterson, A. 1962. Larvae of insects. Part 1: Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera. Ann Arbor, MI: Printed by Edwards Bros. 315 pp.

Pyle, R. 2002. The Butterflies of Cascadia. A Field Guide to all the Species of Washington, Oregon, and Surrounding Territories. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle. 420 pp.

Royer, R.A., J.E. Austin, and W.E. Newton. 1998. Checklist and "Pollard Walk" butterfly survey methods on public lands. The American Midland Naturalist. 140(2): 358-371.

Scott, J.A. 1986. The butterflies of North America. Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, CA.

Stehr, F.W. (ed.). 1987. Immature insects. Vol. 1. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Co. 754 pp.

Triplehorn, C. and N. Johnson. 2005. Introduction to the Study of Insects. Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, CA. 864pp.

22