Acta Sociologica-2006-Halleröd-83-102

Transcript of Acta Sociologica-2006-Halleröd-83-102

-

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

1/21

http://asj.sagepub.com/Acta Sociologica

http://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0001699306061901

2006 49: 83Acta SociologicaBjrn Hallerd and Annika Westberg

Hardship Among Swedish Youthouth Problem: What's the Problem?: A Longitudinal Study of Incomes and Economic

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Nordic Sociological Association

can be found at:Acta SociologicaAdditional servicesand information for

http://asj.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://asj.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.refs.htmlCitations:

What is This?

- Feb 22, 2006Version of Record>>

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83http://asj.sagepub.com/subscriptionshttp://asj.sagepub.com/cgi/alertshttp://www.sagepublications.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.refs.htmlhttp://nordicsociologicalassociation.org/pub/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=63&Itemid=30/http://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.full.pdfhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.full.pdfhttp://online.sagepub.com/site/sphelp/vorhelp.xhtmlhttp://asj.sagepub.com/cgi/alertshttp://asj.sagepub.com/subscriptionshttp://asj.sagepub.com/subscriptionshttp://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navhttp://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navhttp://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.refs.htmlhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.refs.htmlhttp://online.sagepub.com/site/sphelp/vorhelp.xhtmlhttp://online.sagepub.com/site/sphelp/vorhelp.xhtmlhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.full.pdfhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.full.pdfhttp://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://online.sagepub.com/site/sphelp/vorhelp.xhtmlhttp://online.sagepub.com/site/sphelp/vorhelp.xhtmlhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.full.pdfhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.full.pdfhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.refs.htmlhttp://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83.refs.htmlhttp://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navhttp://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navhttp://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navhttp://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navhttp://asj.sagepub.com/subscriptionshttp://asj.sagepub.com/subscriptionshttp://asj.sagepub.com/cgi/alertshttp://asj.sagepub.com/cgi/alertshttp://nordicsociologicalassociation.org/pub/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=63&Itemid=30/http://nordicsociologicalassociation.org/pub/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=63&Itemid=30/http://www.sagepublications.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/content/49/1/83http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

2/21

ACTA SOCIOLOGICA 2006

Youth Problem: Whats the Problem?

A Longitudinal Study of Incomes and Economic Hardship AmongSwedish Youth

Bjrn Hallerd and Annika WestbergUme University, Sweden

abstract: The questions addressed in this study are: first, what factors determinethe economic situation among the young, and, second, what aspects in youth havea long-term impact on their economic situation as adults? The empirical analysisbuilds on a three-wave panel covering a period of 16 years. Growth curve modelling

is used to estimate changes over time. The main results are: Young peoples incomessay little about their current standard of living or future earnings ability. Economicdeprivation during youth is unrelated to the development of deprivation over time.Hence, the finding that young people in general face economic difficulties does notmean a problem with lasting implications. Labour market situation and householdcharacteristics during youth are relativelyl unrelated to development later in life.However, long-term unemployment hampers young peoples economy in the longrun. Most importantly, the results of this analysis emphasize the importance of thereproduction of class and gender relations. It is these two fundamental aspects,more than anything else, that affect young people on their way into adulthood andin their future life as adults.

keywords: adolescence class gender longitudinal sociology structuralequation youth

Introduction

Young people have always been a subject of concern in relation to their youth, i.e. with respectto disturbing youth culture and behaviour (Lindgren, 2002) and with how social changesaffect the transition into adulthood (Bynner et al., 1997; Jones and Wallace, 1992). These

concerns seem justified, because youth is a formative transition phase signified by a succes-sive move through the educational system, labour market establishment and family formationthat, considering the alternative, it is hoped everyone will go through. Furthermore, it is aperiod for many signified by unemployment, economic hardship, uncertainty about the futureand insecurity about ones ability to handle the situation.

Young people are also, increasingly it seems, being pinpointed as losers who lag behindolder generations, i.e. the middle aged, with regard to economic prosperity and career oppor-tunities (cf. Hll and Vogel, 1997). The problem with this reasoning, when repeated over time,is that those who were young losers 20 years ago are middle-aged winners today, or, morecorrectly, some are winners and some are still losers. It is clear that we should be focusing notjust on the conditions among the young at one point in time, but first and foremost onthe long-term impact of conditions prevailing during adolescence. However, although the

Acta Sociologica March 2006 Vol 49(1): 83102 DOI: 10.1177/0001699306061901

Copyright 2006 Nordic Sociological Association and SAGE (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi)

www.sagepublications.com

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

3/21

problems that young people face have been thoroughly discussed in the literature, we knowrelatively little about their long-term impact. We lack the knowledge necessary to determinewhether our worries about young people and their future are justified, and, perhaps even moreimportantly, to determine whether we are worried about the right things. The aim of this studyis therefore to analyse the degree to which circumstances during adolescence affect future

income development and the incidence of economic difficulties in adult life. In doing so, wetake a panel sample of individuals first interviewed in the 1980s when they were between 19and 25 years of age. A second panel wave was completed 8 years later, and the final waveafter 16 years. Hence, the period covers 16 years, and at the third wave the respondents werebetween 35 and 41 years of age.

Young and poor

It is more or less a given fact that a substantial proportion of young people have low incomes(Salonen, 1993, 2000). In most cases the temporality of this situation is also more or less given;

income mobility and changes in economic standard are, for example, immense among thosebelow the age of 30 compared to the middle aged (Bjrklund, 1993). However, there is morethan just a gap between the young and the rest of the population. Since the 1970s, the develop-ment of young peoples incomes has been lower than for the rest of the population (Torge,1997). The main reason has been a general social change resulting in prolonged education, incombination with increasing youth unemployment, leading to a general postponement oflabour market establishment (Banks et al., 1992; Bynner et al., 1997; Jones and Wallace, 1992).

The fact that many young people have low incomes does not necessarily mean that theyactually suffer from economic hardship and a low economic standard, i.e. that they have toforgo vital consumption, that they have problems making ends meet and that they live ineconomic insecurity. First, economic standard is not primarily determined by the individualsincome, but by the households disposable income and the number of people assumed to sharethat income. Thus, as long the young person remains in the nest, it can be assumed s/he sharesat least the common consumption within the household (housing, food, accessories such asTV, etc.).1 For example, a comparison of the situation in different European countries hasshown that young people in Sweden and the other Scandinavian countries are, in relation tothe middle aged, relatively worse off than the young in central Europe and, even more so,compared to those in Mediterranean countries (Vogel, 2002). The main reason is that youngpeople in the northern part of Europe leave the nest earlier than do those in southern Europe.Second, even though a young person has left the nest, it is possible that there is a substantialflow of economic resources from the parents to the child, again obscuring the relationship

between income and economic standard. There is a long list of circumstances that blur therelationship between income and standard of living (cf. Hallerd, 2000), circumstances makingclear the importance of not relying on income data alone when assessing peoples economicstandards, but also of having direct indicators of consumption and economic hardship. Thisis true especially in the case of young people. Vogel and Rbcks (2003) cross-sectionalanalysis of welfare development in Sweden during the past 27 years is an attempt to developsuch indicators. One of their main findings is that young people (2029 years of age) lagbehind the middle aged and that the difference has increased over time. Their result confirmsthe picture of a widening gap between the young and the old. Vogel and Rbck do notanalyse the overlap between their direct measures of economic hardship and low income, i.e.

whether it actually is the case that those with the lowest income have the greatest economicproblems. However, earlier studies indicate that this overlap is surprisingly small (Hallerd,1995, 2000), which is a subject warranting additional research.

Another indicator pointing to economic difficulties among the young is statistics on social

Acta Sociologica 49(1)

84

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

4/21

assistance, which is the only means-tested last resort income support system in Sweden. Inthe transitional phase between the relative dependence of youth and the relative independenceof adulthood, social assistance is a common way of supporting oneself, and this in turnindicates the difficulties in self-support that young people face (Salonen, 1993, 2000). Duringthe first half of the 1980s, young peoples need for social assistance increased, but was not

accompanied by a comparable increase in the adult population. About 5 per cent of thosebetween 18 and 29 years received social assistance in 1981, compared to 11 per cent in 1986(of those over 29, the percentages were 5 and 6.5, respectively) (SCB 1985, 1987). These rela-tively high social assistance figures among the young have since been maintained (SoS, 2005).The fact that the number of recipients of long-term assistance over a long period has beenlower among the older section of the population means that dependency on assistance is notnecessarily connected with long-existing economic marginalization (Salonen, 1993; Strandh,1999).

Thus, we know that a large proportion of young people face economic hardship and thatdevelopment over time has been less than favourable. The questions addressed in this study

are: first, what factors determine the economic situation of the young and, second, what factorsin youth have a long-term impact on peoples economic situation?

Youth and transitions: What determines the outcome?

The distribution of resources and economic well-being is closely related to peoples occu-pational position, i.e. the class structure. Class position influences the distribution of economicresources, but also, and more directly, peoples behaviour (Weber, 1968; Bourdieu, 1984; Scott,1996; Bihagen and Hallerd, 2000). However, we do not assume that young peoples classpositions are of any great importance in our coming to an understanding of their life trajec-tories, simply because they often have not had time to establish themselves on the labourmarket. In this perspective, parents class positions are more relevant to understanding theyouth situation (Wyn and White, 1997). It is also well documented in the literature thatparents economic situation and behaviour influence their children, the choices they make andthe opportunities that are perceived as viable (Hellevik, 1992; Marshall et al., 1996). On thisbasis, it can be assumed that class of origin largely determines level of education, time oflabour market entrance and household formation (Jones and Wallace, 1992; Erikson andJonsson, 1993). Class of origin is therefore important both to understanding the economicsituation among the young when they are young and to understanding their prospects asadults. This assumption builds on the idea that class of origin affects economic situation indi-rectly, owing to the choices and opportunities available to the young transitioning into

adulthood. However, it could be the case that class of origin has a more profound long-termimpact on peoples economic development because of the cultural capital inherent in differentclass positions (Bourdieu, 1984), on the one hand, and the flow of resources between gener-ations (Kohli, 1999), on the other.

Just as class of origin is important in understanding constraints and opportunities, gendertoo is important in these processes. The socialization process continues to be proven to workin the sense that gender shows stable patterns of reproduction in many socially importantcontexts, although there have been changes, and mostly so in womens patterns (Buchmann,1989; Irwin, 1995; Flood and Grsj, 1997). It has been shown that economically differentconditions in youth are less gender segregated than those in adulthood (Nyberg, 1998) and

that there are variations in attitudes (Westberg, 2004a). These differences can be attributed tothe mobile transitional character of being young compared to later establishment on a rela-tively traditionally gender-segregated labour market (Ahrne and Roman, 1997; Rothstein,1999).

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

85

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

5/21

There has always been concern about the consequences of youth unemployment, concernstemming from the fact that young people often experience periods of unemployment beforethey are fully established on the labour market (Heinz, 1999), which, in turn, means that theyare overexposed to unemployment compared to the adult population (Salonen, 1993; Torge,1997). The crucial question is, of course, the degree to which this should be seen as a serious

problem with long-term effects on, among other things, the individuals economic situation,or whether it should be perceived as a more or less natural part of the transition intoadulthood. A recent analysis of the degree to which (2001) the labour market situation in 1990was associated with the occurrence of economic hardship eight years later has shown thatshorter periods of unemployment among the young do not have a detrimental impact oneconomic situation later in life. However, young people who are unemployed for longerperiods suffer from a higher incidence of economic hardship also as adults (Hallerd, 2001) a result supported by Strandh (1999) and Hammer (1997). These findings have to be seen inrelation to the effect of unemployment among older age groups, where short and recurrentunemployment clearly has a detrimental effect on economic situation (Hallerd, 2001). Short-

term unemployment can therefore be claimed to be a normal and quite harmless state in youthconnected with the special circumstances of this part of the life course.The importance of the extent to which young people are exposed to unemployment also

points to the importance of timing of the labour market transition in relation to societysmacro-economic situation. Some may enter an advantageous labour market, making thisestablishment easier (Jones and Wallace, 1992), while others may enter during a recession,which in many cases will affect labour market establishment and time spent in unemploy-ment, with further long-term consequences (Inghe, 1960; Hrnqvist, 1994).

The decision to undertake a longer period of education instead of entering the labour marketaffects the immediate economic situation during youth, as well as further labour marketprospects and earning ability. Students often live at a low economic level, which is seen asacceptable because they are investing in their own human capital, a situation that will presum-ably result in economic rewards later in life (Erikson and Jonsson, 1996). From a societal pointof view, economic hardship among students becomes a problem if they are prevented fromeducating themselves. If so, it can be assumed that this is a problem first and foremost foryoung people whose parents cannot, or will not, support them economically. Such a situationis likely to increase class bias in the selection into higher education. However, this bias remainsa fact. Working class youth are still underrepresented within higher education, despite theSwedish educational system with its generous mix of public allowances and student loans incombination with free education at all levels of the educational system. It has long been thecase that people of working-class origins enter the labour market earlier than do their middle-

class peers. It is argued that an explanation for this phenomenon can be found in the culturaland social denotations of class of origin (Coleman, 1988; Erikson and Jonsson, 1996).Moving from the parental home is expensive and demands some form of income, as has

been emphasized in several studies (Goldscheider and DaVanzo, 1985; Whittington and Peters,1996). Nilsson and Strandh (1999) have shown that employed young people move out of theparental home earlier than the unemployed do, underlining the importance of economicresources. However, the research on this matter is not clear-cut; other studies argue that theunemployed largely leave the parental home early, suggesting that a certain mobility isnecessary to meet the labour markets needs (Murphy and Sullivan, 1986; Jones, 1995). A longeducation and being older when forming a family of ones own are closely connected with

class of origin as well as gender. Thus, it follows from the fact that people with working-classorigins establish themselves on the labour market earlier, that they also leave the nest andhave children at an earlier time.

Parenthood is a central aspect of the transition into adulthood, not least for the young

Acta Sociologica 49(1)

86

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

6/21

persons own perception of being an adult member of society (Westberg, 2004b). However,parenthood is not just a question of responsibility and the sense of being an adult, it has directeffects on personal economic situation as well. It has previously been shown that changes inhousehold composition constitute one of the most important factors underlying changes ineconomic conditions (Hallerd, 1999).

The aspects discussed above are all assumed to affect transitional patterns and experiencesof moving through the process of establishment. In the following section, an analytic modelis presented bringing these aspects together and setting the stage for the empirical analysis.

Analytic model

The empirical analyses to be conducted utilize longitudinal data covering a 16-year period,starting around 1980, and consist of a population at the time between 19 and 25 years of age.During these 16 years, information was gathered on 3 occasions, so there are 8 years betweenevery point of measurement (for information about the data set, see below). The point of

departure for the empirical analysis is taken in Figure 1. Three blocks of factors are distin-guished, the first containing year of birth, gender and class of origin. These aspects areexogenous, internally unrelated and invariant over time. The rationale for including genderand class of origin is discussed above, but not for year of birth. Even though the analysis coversonly a very narrow age span, there are probably significant age differences in the populationat the first point of measurement; the only reason for including age is to keep these differencesunder control. We do not expect age to have any long-term impact, but we do expect that agewill affect the situation at t0. The second block in Figure 1 contains information about labourmarket affiliation, education and household formation at t0, i.e. these factors are assumed tocapture some of the most important characteristics that, as discussed above, distinguishbetween different categories of youth. The second block is assumed to be dependent on thefirst block; labour market affiliation is, for example, assumed to be influenced by age, genderand, of course, class of origin. We believe that the characteristics within block two are inter-nally related, although no assumptions about causation are made. We do not assume thatpeople have left the nest because they are employed or studying and therefore are notemployed. The obvious reason is that the direction of causation in these cases could be the

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

87

Figure 1 Analytic model

Income levelt0

Economic diff.

t0

Change:

Economic diff.

t0 t1 t2

Change:

Income

t0 t1 t2

Parents class

Educational

attainment

Student

Unemployment

Household

formation

Age

Gender

Block 1 Block 2 Block 3

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

7/21

opposite, i.e. some people will study because they cannot find a job and some will workbecause they have left the nest.

The last block consists of indicators of economic circumstances and changes over time inthese circumstances, i.e. the basic outcome variables. Income level and incidence of economicdifficulties at t0 are measured. We believe that income level and economic difficulties co-vary,

but we do not assume a causal relationship. Furthermore, we assume that change in incomeand change in economic problems over time are affected by the starting level at t 0. Finally, weassume that change in income relates to change in economic difficulties; that is, if incomeincreases we believe that the incidence of economic problems decreases, but we do not assumea unidirectional causal relationship because economic problems could lead people to increasetheir earnings. The model facilitates analysis of the impact of class, gender and other vitalcircumstances on the economic situation during youth itself and the development over timeas the transition into adulthood takes place.

Data, operationalizations and method

The analyses are based on data from the annual Swedish Survey of Living Conditions (ULF)(Hll and Vogel, 1997). ULF is based on a representative sample of the Swedish populationaged 16 to 84 years. In 1979, a panel approach was introduced and since then a subsample hasbeen re-interviewed every eighth year. Thus, it is now possible to analyse a 3-wave panelcovering a period of 16 years. To maximize the available sample size, data from 1979, 1980,1981 and 1982 are merged. The panel samples from these four years were re-interviewed asecond time in 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989 and 1990 and a third time in 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997 and1998.2 The average non-response rate was 14.4 per cent during 197982, increased to anaverage of 21.0 per cent for 198690 and 21.3 per cent during 199498. For the sake ofconvenience, the first panel wave will be labelled t0, the second t1 and third t2. The workingsample has been limited to those who were between 19 and 25 years old at the first wave, andaccordingly between 35 and 41 years when data for the third wave were collected. Theworking sample is made up of 1435 respondents, representing those who participated at allthree waves.

The main outcome variables are income and an indicator of economic difficulties. Incomeis measured as the individuals income before tax recalculated to 1998 prices. Hence, what isanalysed is the overall capacity to earn an income regardless of income source and taxation.The income measure must not be viewed as a direct indicator of economic well-being. Taxeswill of course impact on the amount of money left for consumption, and we do not know thehouseholds, i.e. the consumption units, income or size. By focusing on the individuals

income, we do not risk blurring the analysis by the substantial changes in disposable incomeand, even more so, in equivalent disposable income caused by changes in household compo-sition. The distribution of the income variable is given in Table 1.

Instead of using income, direct information based on survey questions is used as an indi-cation of economic standard, or, more correctly, as an indicator of the incidence of economicproblems. The indicators are displayed in Table 2. There is no discernible trend among thesingle indicators. Trouble making ends meet actually increases over time, while, for example,it becomes less common to borrow from family or friends in order to buy food or pay the rent.The indicators are summarized into an index, henceforth referred to as the deprivation index,which varies between zero and seven. Mean values and standard deviations are given in Table

1. The deprivation index also shows an unambiguous trend over time, decreasing between t0and t1, thereafter increasing again at t2. Evaluating the degree to which this developmentmirrors the general economic development t2being affected by the deep recession at thebeginning of the 1990s or whether it reflects a life course pattern in which the worsening

Acta Sociologica 49(1)

88

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

8/21

situation between t1 and t2 is mainly caused by family formation and, more specifically, parent-

hood, is beyond the scope of this article.Income and the deprivation index constitute the outcome variables in this study. Thequestion is: What circumstances affect the outcome? A number of variables related to theearlier discussion are introduced in the analysis. The distributions of the variables are givenin Table 3 and are operationalized as follows. Age is based on year of birth and gender on therespondents sex. Now, age might be seen as superfluous, as the population covers a restrictedage span from the beginning. However, the age span covers a volatile period in most peopleslives; there is usually a great difference between being 19 and being 25. Thus, age is used asa control for systematic age differences. In addition, interactions between age and the variablesrelated to block 2 in Figure 1 have also been tested. However, there is only one interactionthat, in the end, had any significant impact, and hence is included in the analysis; this inter-action is between being a student and age.

Class of origin refers to the Swedish socio-economic classification schema (SEI), which isdesigned to identify labour market positions that have similar qualification requirements tofill the position. Respondents were asked about their parents main occupation duringupbringing. Six different classes are identified: (1) Blue-collar workers are those who domanual labour. No distinction is made between positions that demand vocational training andthose that do not. (2) Lower white-collar workers occupy a non-manual position requiring atleast some secondary schooling. (3) Middle white-collar workers hold positions that requireat least three years of upper secondary schooling. (4) Higher white-collar workers holdpositions that normally require a university degree. Professional entrepreneurs, such as archi-

tects and doctors, are included in this group. Besides these four groups of employed indi-viduals, two categories of self-employed are distinguished. Thus, the fifth class is made up ofall self-employed individuals, except farmers, who form the sixth and final category. In the

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

89

Table 1 Deprivation index and pre-tax income for panel sample and cross-sectional sample. Mean values andstandard deviations

Cross Cross Crosssection section section1925 2733 3541

t0 t1 t2 197982 198690 19948

Total annual pre-tax income (SEK)mean value 115,554 169,666 198,962 113,101 166,089 194,593std. deviation 57,009 76,476 103,865 58,917 79,333 156,126

Deprivation indexmean value 1.44 1.20 1.33 1.57 1.28 1.49std. deviation 1.39 1.37 1.47 1.49 1.43 1.60

Table 2 Indicators of economic difficulties (per cent)

t0 t1 t2

Trouble making ends meet the past 12 months 17.8 18.7 22.6Borrow money from family or friends to be able to buy food 10.1 9.1 9.1Borrow money from family or friends to be able to pay the rent 4.7 2.8 3.1Unable to pay the rent for a period of time 2.2 2.2 1.8

Cannot get hold of 14,000 SEK within a week if necessary 19.0 11.6 16.1Has to borrow to be able to get hold of 14,000 SEK within a week 36.8 31.2 27.0Cannot afford a one-week holiday trip away from home 34.1 32.5 36.9

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

9/21

first panel wave, only the fathers occupation was enquired about, while in the two subse-quent waves also the mothers occupation. In cases where the mothers and fathers classpositions diverged, the highest class position was assigned as class of origin. If both parentswere employed, this operation is relatively straightforward, following the hierarchy from blue-collar workers to higher white-collar workers. If one parent was a farmer and the otheremployed, class of origin was set to farmer. If one parent was self-employed, class of originwas set to self-employed, regardless of the other parents class position.

We are not, for the reasons outlined above, analysing the impact of the respondents ownclass position at t0. Instead, we use a number of other indicators regarding the youths

situation. The first category to be differentiated is students. However, a significant share of thepopulation had completed their education already at t0, making it important also to analysetheir educational attainment. Five different educational levels are operationalized: (1) compul-sory school only, (2) at most two years vocational training, (3) more than two years ofsecondary education, (4) at most less than three years of tertiary education and, (4) three ormore years of tertiary education.

Unemployment is indicated by two dummy variables measuring self-reported unemploy-ment experience during the previous five years.3 The first, which is labelled short-term unem-ployed, discriminates those unemployed for less than six months during the previous fiveyears, and the second, consequently called long-term unemployed, covers those unemployed

more than six months during the previous five years. The household situation at t0 is indicatedby two variables. The first one, nest-leaving, differentiates between those who have left theparental home and those still living with their parents. The second, parenthood, discriminatesthose who have their own children. The final variable, indicating economic vulnerability,

Acta Sociologica 49(1)

90

Table 3 Sample characteristics. Panel sample and cross-sectional sample (per cent)

Cross-sectionalCategorical variables Panel sample sample

Women 48.7 50.8

Class of originBlue-collar worker 47.2 48.5Lower white-collar 7.5 7.7Middle white-collar 12.9 12.9Higher white-collar 10.1 9.9Self-employed 14.0 13.5Farmer 8.3 7.5

Educational attainmentCompulsory school only 25.6 26.5At most two years of vocational training 29.7 34.4**More than two years of secondary education 11.6 13.6

At most two years of tertiary education 22.2 18.5**More than two years of tertiary education 10.9 6.9***

Studying 21.5 20.1Employed 74.9 73.5Short-term unemployed (126 weeks during the

past five years) 25.2 26.2Long-term unemployed (27 weeks or more during the

past five years) 9.1 11.0Left the parental home 68.5 73.6**Children of their own 15.2 22.9***Recipients of social assistance 1.5 3.1**

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

10/21

measures whether the respondent has received social assistance at any time during the previous12 months.4 This variable departs from the indicators that make up the deprivation index,because it is not just dependent on the respondents interpretation of the situation, but also onthe fact that the situation has been evaluated and that need for assistance has been confirmed.

The availability of longitudinal data represents a great step forward for youth research,

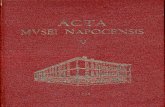

enabling analysis of the long-term impact of conditions during youth. However, longitudinaldata have one serious drawback, especially if they cover a relatively long time span; theytempt us to draw conclusions about todays society based on conditions that prevailed duringan earlier period. To mitigate this problem of relevancy, one strategy used here is to base theanalysis on aspects that repeatedly, and over a long period of time, have been shown to beimportant for the structure of economic rewards and living conditions. Another strategy is toplace the analysis in a historical context, comparing the conditions in our cohort with thesituation among todays youth. Because ULF is an ongoing survey programme, a number ofvariables can be utilized in time series. Figure 2 displays the difference in unemployment,

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

91

Figure 2 Unemployment, lack of cash margin, employment and social assistance among 1925-year-old and3541-year-old Swedes. Ratio describes the relative difference between the two age groups. 19752001 (19832000for social assistance)

Unemployment

0.00

2.00

4.00

6.00

8.00

10.00

12.00

14.00

16.00

5791

7791

9791

1891

3891

5891

7891

9891

1991

3991

5991

7991

9991

1002

Year

deyolpmenutnecreP

Unempl. - 35-41 Unempl. - 19-25 Ratio

Lack of cash margin

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

5791

7791

9791

1891

3891

5891

7891

9891

1991

3991

5991

7991

9991

1002

Year

nigramhsactuohtiwtnecreP

No margin - 35-41 No margin 19-25 Ratio

Employment rate

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

5791

7791

9791

1891

3891

5891

7891

9891

1991

3991

5991

7991

9991

1002

Year

deyolpmetnecreP

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

oitaR

Empl. Rate -35-41 Empl. Rate - 29-25 Ratio

Social assistance

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

3891

4891

5891

6891

7891

8891

9891

0991

1991

2991

3991

4991

5991

6991

7991

8991

9991

0002

Year

ecnatsi

ssalaicosgniviecertnecreP

Soc ass - 35-41 Soc ass - 19-25 Ratio

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

11/21

-

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

12/21

specified with a relation of 0 with the t0 measure, 2 with the t1 measure and 3 with the t2measure, expressing a curve-linear rather than a linear function of time. A linear function hasbeen applied for the measurement of deprivation slope.

The means of the manifest variables are constrained to zero. This, along with the fixedrelations between the latent variables and the manifest variables, allows the latent variables

to function as a container of parameters of the random coefficients model. Thus, for theIntercept latent variable, a mean and a variance are estimated, where the variance representsindividual differences in the intercept of the growth model. For the Slope variable as well, amean and a variance are estimated, and here the variance parameter represents individualdifferences in linear change over time. Thus, the SEM approach allows straightforwardspecification, estimation and interpretation of the growth models.

Results

In order to arrive at a model that is as parsimonious as possible, the following approach has

been applied. The starting-point is taken in a full model estimating all relationships thatfollow from the analytic model in Figure 1. That is, the variables in the first block affect all theothers, variables in block two are correlated and the variables in block three are affected byall previous variables at the same time as they are interrelated, as shown in the figure. Insig-nificant estimates (t-value less than 1.96) have thereafter been lifted from the model one byone in order to find a parsimonious model that fits the data at least as well as the full model.The strategy resembles what Jreskog (1993) called model generating, and as a result onlysignificant estimates are displayed in the tables.5 The model has been specified in STREAMS2.5, and estimated with AMOS 4. The results are displayed in two different tables. Table 4gives parameters for the relationship between the exogenous variables age, gender and classof origin, and the set of endogenous variables that indicate the youth situation. Thus, the tablerelates to manifest variables in the first two blocks of the analytical model (Figure 1).

Relationships between manifest variablesIn Table 4 we can see that the older the population becomes, the more likely it is that theyhave attained a longer education, are employed, have left the nest, and have a child of theirown. Hence, the pattern revealed is more or less what can be expected when analysing a popu-lation that is presumably in the transitional phase into adulthood. The next variable, gender,is more interesting, as it reveals substantial differences between women and men. Both short-term and long-term unemployment are more common among women. This is also true forsocial assistance, although it has to be kept in mind that this variable is problematic due to

underreporting (see endnote 3). As expected, women also leave the nest earlier than men do,and they are also more likely to become a parent at a young age.Estimates related to class of origin should be interpreted as contrasts to the reference group,

which in this case consists of blue-collar workers. It is apparent that those with middle andhigher white-collar worker class of origin deviate from the rest. Here we find a higherincidence of higher education and a larger share of students, especially among the oldersections of the population; this is shown by the impact on the interaction between being astudent and age (older students, who are usually those involved in tertiary education, moreoften come from white-collar homes). As a natural consequence, being unemployed is lesslikely if the class of origin is middle or higher white-collar worker. It is also less common that

people with a white-collar background have children of their own at a young age. Thus, Table4 confirms a picture that, on the basis of earlier research, we more or less expected. The repro-duction of a class society shines through the results of the analysis and there is also a genderedpattern showing that young women seem to become what is commonly defined as adults

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

93

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

13/21

94

Table 4 Growth curve model estimation. Standardized regression and correlation coefficients

Dependent variables

Secondary Secondary Unemployed UnemPrimary edu. < 3 edu. 3 Tertiary Interaction < six six

Independent variables edu. years years edu. Student age*student Employed months month

Age 0.08 0.07 0.14 0.14 0.10Gender 0.05 0.08 0.08Class of origin(blue-collar ref. gr.)

Lower white-collar 0.07 0.08Middle white-collar 0.08 0.08 0.10 0.19 0.15 0.06 0.09Higher white-collar 0.13 0.09 0.08 0.12 0.24 0.16 0.14 0.07

Self-employed 0.06 0.07 Farmer

Education (primary ref. gr.)Secondary < 3 years 0.05#Secondary 3 years 0.04#Tertiary < 3 years Tertiary 3 years

Student 0.22#Employed 0.07#Unemployed < six months 0.05#Unemployed six months Nest leaving

Chi-square = 609.20, Degrees of freedom = 141, RMSEA = 0.048.For all displayed variablesp < 0.05.# Specified as covariation. Parameter estimated but not significant.

at UNI VO

FCALI FORNI ASANTACRUZonMarch6

2014

asj sagepubcom

Downl oadedf rom

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

14/21

earlier, because of their earlier nest-leaving and higher likelihood of becoming a parent at anearly age. In addition to the regression estimates (specified as causal relations), correlationsare also estimated between the variables relating to block two of Figure 1. The significantresults are given in Table 4 (denoted by #) and reveal that students, no surprise, tend not tobe employed. It is also the case that the employed are less prone to have an unemployment

history and that young people with higher education tend to have children to a lesser extent.Finally, it is revealed that having children and nest-leaving are positively correlated. Let usnow move on to the core of the analysis.

Latent variablesIn Table 5, the relationships between all the manifest variables related to the first two blocksof Figure 1 and the latent variables are displayed, i.e. income intercept, deprivation intercept,income slope and deprivation slope. The parameters represent first the direct standardizedregression and, when appropriate, the correlation coefficient. However, the direct effects onlytell part of the story, because a substantial component of the impact in a complex causal model

is indirect. Looking only at the direct effects will therefore erroneously lead us to believe thata number of variables are unimportant. Therefore the total effect (indirect + direct) is alsodisplayed both as standardized and unstandardized coefficients.

Income interceptAs expected, the income intercept increases with age. Because of an indirect impact, the totaleffect is higher than the direct effect and the unstandardized coefficient reveals that incomeincreases by approximately SEK 8600 every year. A more interesting result is the differencebetween women and men. There is a clear gender gap already at this early stage of the lifecourse, and the total effect shows an annual income difference of almost SEK 16,000. The smallindirect effect of gender is attributable to womens exposure to unemployment and earlyparenthood. The direct impact of class is relatively small, but reveals that white-collar origin(middle and high) is associated with a low income intercept. The total effects are considerablylarger and amplify the differences between those with a blue-collar origin and those with awhite-collar background. The indirect effect is mainly caused by the higher probability amongthose with a white-collar origin of studying and, hence, of not being employed. Educationalattainment does not affect income intercept. Unsurprisingly, being a student has a negativeeffect on income intercept. The same holds for unemployment, especially long-term unem-ployment and parenthood, while employment naturally increases the income.

Deprivation intercept

In concordance with the result for income intercept, the intercept for deprivation decreaseswith age. Gender does not directly affect deprivation intercept, but there is a substantialindirect effect showing that women are more prone to report economic difficulties. The indirecteffect is mediated by young womens higher probability of leaving the nest at an early age,being a parent, being unemployed and receiving social assistance. Again it is revealed that thedirect impact of class is minor, but that the indirect effect is substantial, as class affects almostevery one of the manifest variables that are assumed to be intermediate to class and the latentvariables. An important aspect to note is that those with a middle range or higher white-collarorigin not only have the lowest income intercept, they also have the lowest deprivationintercept. Hence, their income situation does not correspond with their experience of economic

difficulties.The educational effect is harder to understand. The level of education after primary school(7 to 16 years of age) does not seem to be particularly important, even though there are somedifferences. The main gap is between those who have only a primary school education and

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

95

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

15/21

96

Table 5 Growth curve model total effects, regression estimates, standardized regression estimates and correlation estimate

Dependent variables

Income intercept Deprivation intercept Slope income

Std. Std. Un-std. Std. Std. Un-std. Std. Std. Un-direct total total direct total total direct total tota

Independent variables effects effects effects effects effects effects effects effects effe

Age 0.33 0.39 8613 0.21 0.16 0.07 0.11 1Gender 0.16 0.18 15,738 0.11 0.20 0.42 0.36 21Class of origin(blue-collar ref. gr.)

Lower white-collar 0.01 1459 0.07 0.22 0.04 4Middle white-collar 0.05 0.12 15,332 0.12 0.31 0.10 0.23 19Higher white-collar 0.07 0.18 26,122 0.13 0.36 0.06 0.23 22Self-employed 0.04 4841 0.07 0.11 0.28 0.06 0.11 8

Farmer 0.01 1620 0.04 0.11 0.02 2Education (primary ref. gr.)

Secondary < 3 years 0.21 0.21 0.40 0.06 0.10 6Secondary 3 years 0.20 0.20 0.55 0.09 0.13 12Tertiary < 3 years 0.22 0.22 0.47 0.09 0.14 9Tertiary 3 years 0.26 0.26 0.71 0.12 0.17 16

Student 0.28 0.28 31,944 0.08 0.08 0.18 0.21 0.35 26Interaction age*stud 0.21 0.21 0.12 0.04 8Employed 0.52 0.52 52,811 0.22 14Unemployed < six months 0.02 1793 0.14 0.14 0.29 0.02 1Unemployed six months 0.10 0.10 14,706 0.26 0.26 0.77 0.01 1Nest leaving 0.09 0.09 8513 0.22 0.22 0.41 0.08 5

Parenthood 0.19 0.19 22,643 0.08 0.08 0.20 0.06 5Social assistance 0.29 0.29 2.32 0.07 0.06 1Income intercept 0.15# 0.42 0.42Deprivation intercept 0.21 0.21 7Slope income

Chi-square = 609.20, Degrees of freedom = 141, RMSEA = 0.048.

at UNI VO

FCALI FORNI ASANTACRUZonMarch6

2014

asj sagepubcom

Downl oadedf rom

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

16/21

the rest. A speculative interpretation would be to suggest that those who have only a primaryschool education are a selected group and that the mechanism leading to early drop out fromthe educational system is connected with the probability of ending up in an economicallydifficult situation.

The fact that students score relatively low on the deprivation intercept should be interpreted

in the light of the negative effect of the interaction term between age and being a student. Theinteraction shows that the longer a person remains in the educational system, the greaterher/his economic problems. Hence, there is a price to be paid for investment in human capital.Unemployment, nest-leaving, parenthood and social assistance are all related to a high depri-vation intercept. The last of these, social assistance, is worth further comment. It is notassumed that social assistance per se leads to economic difficulties; if anything, the directionof causation should be the opposite. However, receiving assistance can also be interpreted asan indicator of an overall difficult situation, and from that perspective it is reasonable toconstrue assistance as an indicator of economic difficulties. It can be noted, finally, that incomeintercept correlates with deprivation intercept in the way one would expect, i.e. the higher the

income, the less serious ones problems.

Income slopeThe age effect is, as expected, minor and only indirect. The effect of gender on income slopeis great, direct and important. Compared to men, womens income development not onlybegins at a lower level (income intercept), it also grows considerably more slowly over time.The total effect reveals that women start with an income about SEK 16,000 lower than thatof men, and then continue with a growth rate average around SEK 21,000 lower over the 16-year period. The direct impact of class of origin is positive but small, yet the total impact issubstantial. The incomes of middle and higher white-collar worker parents increase con-siderably more than those of parents from a blue-collar or farming background. The indirecteffect of class background operates mainly via educational attainment and student status, i.e.those who already had or were about to obtain a higher education at t0 had the most favour-able income development, something shown not least by the direct estimates for thesevariables. Hence, education pays off. More interesting is the fact that there are no direct effectsof employment, unemployment, nest-leaving and early parenthood. However, with theexception of parenthood, they all have some negative effect on income slope, mainlymediated via income intercept and deprivation intercept (those with a relatively high incomeat t0 had a slower growth rate, at the same time as those who experienced economic diffi-culties had a somewhat faster growth rate). An interesting observation is that recipients ofsocial assistance at t0 actually had a slightly better income development over time than did

others.

Deprivation slopeAgain, a clear gender difference is observed. Women have a less favourable development asregards economic difficulties. The direct effect of 0.18 is reduced to a total standardized effectof 0.12. Hence, economic difficulties within this particular age cohort are, other things beingequal, increasingly affecting women, which is a result in line with other findings showing thatwomen, although married (formally or informally), experience economic difficulties to a largerextent than do men (Pahl, 1989; Hallerd, 1997; Nyman, 2002). The gender effect is mediatedvia nest-leaving, parenthood and social assistance at t0. Nest-leaving and, again worth noting,

social assistance decrease the growth of economic difficulties, while parenthood increases thegrowth rate. Hence, the negative impact of nest-leaving and social assistance on economicdifficulties in youth is counterbalanced over time. This is not the case for early parenthood being a young parent not only has a detrimental effect on the youth situation, it is also

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

97

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

17/21

connected with the continuation of growing economic difficulties. Finally, it can be seen thatthere is a correlation between income slope and deprivation slope the better the incomedevelopment, the less serious ones economic difficulties.

Discussion and conclusionsThe part of the structural analysis that concerned the manifest variables showed a youthsituation pattern that was very much as expected. Class of origin had a decisive impact onyoung peoples opportunities and choices. Children of blue-collar workers were generally lesslikely to educate themselves, more likely to be unemployed and have children of their own.In addition to and independent of the class difference, there was also a substantial gender gap.Young women were more often unemployed, more likely to have left the nest and also morelikely to have a child of their own. There was also a significant gender difference with regardto social assistance.

The central purpose of this study was to investigate the economic situation both during

youth and afterwards, i.e. the long-term impact of conditions during youth on changes ineconomic conditions. The situation during youth was measured with two latent variables:income intercept, measuring income at t0, and deprivation intercept, measuring the incidenceof economic problems at t0. Change over time was measured with two additional latentvariables: income slope represented the change in income between t0 and t2, while depriva-tion slope measured the change in economic difficulties between t0 and t2. The most strikingaspect was the impact of class of origin and gender. Parents class position did not have anyparticularly strong direct impact on the economic situation. The fundamental importance ofclass of origin for opportunities and choices during youth was instead clearly visible in thestrong indirect effects. Low income during youth was, it seemed, primarily a problem forchildren of middle range and higher white-collar workers. However, there were no signs thatwhite-collar origin was in any way associated with economic deprivation during youth. Onthe contrary, it seemed that it was children of blue-collar workers who suffered the greatesteconomic difficulties. We can therefore conclude, in accordance with earlier research, that lowincome among the young is not automatically connected with economic hardship. We canfurther assume that this situation is explained, to a large degree, by the ability of parents totransfer resources, monetary or otherwise, to their children.

Class of origin was also important for the development of income over time. The patternwe found was very much expected white-collar origin, especially middle range and higher,was associated with a rapid increase in income. Changes in deprivation were less affected, butit was shown that the favourable situation of those with a white-collar background was main-

tained or even further improved.It is important to stress the gender difference. Women had lower incomes in youth and theywere more deprived. This situation was not counterbalanced by the development over time,but was, on the contrary, exaggerated, with both income and deprivation developing lessfavourably for women compared to men. The gender differences were not an effect of womenseducational choices (no difference between the sexes is observed), neither were they causedby other circumstances controlled for in the model (unemployment, nest-leaving, parenthood,social assistance). It was rather the case that the indirect effects offset the direct gender effect.Thus, women face a more difficult economic situation during youth, mainly because they arewomen and partly because they, as such, are more exposed to situations that detrimentally

affect their economic situation. However, womens unfavourable development over time isnot explained by these situations in youth; the explanation should rather be sought in thegendered structure of society a structure that systematically influences labour market careersand family obligations during youth as well as adulthood.

Acta Sociologica 49(1)

98

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

18/21

The other variables measuring the situation during youth had less clear-cut impacts. Youngpeople who studied had, as expected, low incomes and the longer they studied the more econ-omically deprived they tended to be. Yet, in a longer perspective, the investments in humancapital resulted in a more rapid income increase and a decrease in economic difficulties. Long-term unemployment in youth was associated with low income and a high incidence of

economic deprivation during youth, but the long-term impact was small. Youth unemploy-ment was not associated with an increase of economic difficulties over time. However, therewere no signs that the (long-term) unemployed would make up for their unfavourable startingposition later on in life. Thus, the economic losses induced by unemployment in youth are inmost cases not regained in adulthood. The result also confirms that a shorter period of unem-ployment during youth is a fairly unproblematic phenomenon.

The negative effect in youth of nest-leaving was more or less counterbalanced duringadulthood by a relatively positive income development and negative growth in economicdeprivation. Also early parenthood was related to economic problems in youth, but in thiscase future development was not positive and there seems to be a long-standing impact on

the incidence of economic deprivation. Recipients of social assistance reported a much higherincidence of deprivation than did any other group. It is important to note, however, that thedevelopment over time was not terribly poor and that this group showed the greatest decreasein deprivation. Hence, it could not be shown that recipients of assistance were losers in thelong run.

The main conclusions to be drawn are the following:

Young peoples incomes do not say very much about their current standard of living orfuture earning ability. If anything, low income is a predictor of substantial future incomegrowth. There are good reasons for being sceptical regarding the importance of analysingthe income situation of young people and the incidence of income poverty among the

young. Being economically deprived during youth is unrelated to the development of deprivationover time. Hence, the finding that young people in general face economic difficulties doesnot imply that we are observing a problem with lasting implications.

Labour market situation and household characteristics during youth are only modestlyrelated to the development later on in life. However, long-term unemployment hampersyoung peoples economy, and there is nothing in this study to indicate that this situationwill be counterbalanced over time.

Most importantly, the results of this analysis emphasize the importance of the reproductionof class and gender relations. It is these two fundamental aspects, more than anything else,that affect young people on their way into adulthood and in their future life as adults. So,back to basics fight class differences and promote gender equality.

Notes

The Swedish Council for Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities and the Swedish Council forWorking Life and Social Research financially supported this research. Comments on previous drafts fromPeter Waara, Jan-Eric Gustafsson and anonymousActa Sociologica referees are gratefully acknowledged.

1. Income data for Sweden have long been hampered by an incomplete household definition. As soonas a person turns 18, s/he has been treated as a specific household unit, regardless of whether any

real change has occurred. Hence, a significant number of young people, still living in their parentalhome, are registered as having extremely low disposable household income. The incidence of povertyamong the young is therefore overestimated and among older populations underestimated (Hallerd2000). In a more recent publication of income distribution, Statistics Sweden has corrected this error.

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

99

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

19/21

2. The sample from 1979 is about twice as large as the latter sample, and the panel is split so that halfthe sample was re-interviewed in 1986 and the other half in 1987.

3. The self-reported variable covers unemployment experienced by school leavers and trainees withoutjobs.

4. From 1983 onwards, it is possible to derive information about social assistance from the income

register attached to ULF. Because this option is not available for the t0 observation in this study, theindicator is based on information from a question in ULF. Comparing the question with register datain later ULF surveys reveals that the question underreports the extent of social assistance.

5. In addition to those displayed are the correlations between sets of dummy variables estimated, i.e.dummies for class of origin, education and unemployment. This is necessary to get an acceptable fitof the model, but reflects nothing more than the obvious fact that they are mutually exclusive. Forthe exogenous class dummies, it is the observed variables that are allowed to co-vary, while for theendogenous education and unemployment dummies, it is the error term that co-varies.

References

Ahrne, G. and Roman, C. (1997) Hemmet barnen och makten: Frhandlingar om arbete och pengar i familjen.Stockholm: Fritzes.Banks, M., Bates, I., Breakwell, G., Bynner, J., Emler, N., Jamieson, L. and Roberts, K. (1992) Careers and

Identities. Buckingham: Open University Press.Bihagen, E. and Hallerd, B. (2000) The Crucial Aspects of Class: An Assessment of the Relevance of

Class in Sweden from the 1970s to the 1990s, Work, Employment and Society 14: 30730.Bjrklund, A. (1993) A Comparison Between Actual Distribution of Annual and Lifetime Income:

Sweden 195189, Review of Income and Wealth 39: 37787.Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Buchmann, M. (1989) The Script of Life in Modern Society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Bynner, J., Chisholm, L. and Furlong, A. (1997) Youth, Citizenship and Social Change in a European Context.

Aldershot: Ashgate.Coleman, J. (1988) Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital, American Journal of Sociology 94

(Suppl): 95120.Erikson, R. and Jonsson, J. O. (1993) Ursprung och utbildning: Social snedrekrytering till hgre studier.

Stockholm: Allmnn Frlaget.Erikson, R. and Jonsson, J. O. (1996) Can Education be Equalized? The Swedish Case in Comparative Perspec-

tive. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.Flood, L. and Grsj, U. (1997) Tid fr barn, tid fr arbete, in G. Ahrne and I. Persson (eds) Familj, makt

och jmstlldhet, pp. 15988. Stockholm: Fritzes.Goldscheider, F. K. and DaVanzo, J. (1985) Living Arrangements and the Transition to Adulthood,

Demography 22: 54563.Hallerd, B. (1995) The Truly Poor: Indirect and Direct Measurement of Consensual Poverty in Sweden,

Journal of European Social Policy 5: 11129.Hallerd, B. (1997) Lika hushll, olika ekonomi. Ekonomiska problem bland samboende mn ochkvinnor, in G. Ahrne and I. Persson (eds) Familj, makt och jmstlldhet, pp. 10422. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Hallerd, B. (1999) Economic Standard of Living: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Economic Standardamong Swedes 19791995, European Societies 1: 391418.

Hallerd, B. (2000) Socialbidragstagande och fattigdom, in A. Pudie (ed.) Socialbidrag i forskning och ipraktik, pp. 6186. Gteborg: Gothia.

Hallerd, B. (2001) Employment Positions, Class and Economic Hardship, in B. Furker (ed.)Employment, Unemployment, Marginalization: Studies in Contemporary Labour Markets, pp. 12350.Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Hallerd, B. and Gustafsson, J.-E. (2003) A Longitudinal Analysis of the Relationship Between Changes

in Socio-Economic Circumstances and Changes in Health. Working paper, Department of Sociology,Ume University.Hammer, T. (1997) History Dependence in Youth Unemployment, European Sociological Review 13: 1733.

Acta Sociologica 49(1)

100

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

20/21

Heinz, W. R. (1999) From Education to Work. Cross-National Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Hellevik, O. (1992) Introduction to Causal Analysis. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.Hoyle, R. H. (1995) Structural Equation Modeling. London: Sage.Hll, L. and Vogel, J. (1997) Vlfrd och ojmlikhet i 20-rs perspektiv 19751995. rebro: Statistiska

Centralbyrn.Hrnqvist, M. (1994) Att bli vuxen i olika generationer, in J. Fritzell and O. Lundberg (eds) Vardagensvillkor, pp. 184214. Stockholm: Brombergs.

Inghe, G. (1960) De fattiga i folkhemmet. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.Irwin, S. (1995) Rights of Passage. London: UCL Press.Jones, G. (1995) Leaving Home. Buckingham: Open University Press.Jones, G. and Wallace, C. (1992) Youth, Family and Citizenship. Buckingham: Open University Press.Jreskog, K. G. (1993) Testing Structural Equation Models, in K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (eds) Testing

Structural Equation Models, pp. 294316. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Kohli, M. (1999) Private and Public Transfers Between Generations, European Societies 1: 81104.Lindgren, S. (2002)Modernitetens markrer: Ungdomsbilder i tid och rum. Ume, Department of Sociology,

Ume University.Marshall, G., Roberts, S. and Burgoyne, C. (1996) Social Class and Underclass in Britain and the USA,

British Journal of Sociology 47: 2244.McArdle, J. J. (1988) Dynamic But Structural Equation Modeling of Repeated Measures Data,

pp. 561614 in J. R. Nesseroad and R. B. Cattell (eds)Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology.New York: Plenum Press.

Meredith, W. and Tisak, J. (1990) Latent Curve Analysis, Psychometrika 55: 10722.Murphy, M. and Sullivan, O. (1986) Unemployment, Housing and Household Structure Among Young

Adults,Journal of Social Policy 15: 20522.Muthn, B. and Khoo, S. T. (1998) Longitudinal Studies of Achievement Growth Using Latent Variable

Modelling. Learning and Individual Differences. Special issue. Latent Growth Curve Analysis 10: 73101.Nilsson, K. and Strandh, M. (1999) Nest Leaving in Sweden. The Importance of Early Educational and

Labourmarket Careers,Journal of Marriage and the Family 61: 1068 79.Nyberg, A. (1998) Women, Men and Incomes. Stockholm: Fritzes.Nyman, C. (2002)Mine, Yours or Ours. Ume: Department of Sociology, Ume University.Pahl, J. (1989)Money and Marriage. London: Macmillan Education.Rogosa, D. R., Brandt, D. and Zimowski, M. (1982) A Growth Curve Approach to the Measurement of

Change, Psychological Bulletin 92: 72648.Rothstein, B. (1999) Den moderna knsmaktsordningens grundbult, Statsvetenskaplig tidsskrift 102: 120.Salonen, T. (1993)Margins of Welfare. Kristianstad: Hllestads Press.Salonen, T. (2000) Ungdomars socialbidragstagande och frsrjningssvrigheter under 1990-talet, in

. Bergmark (ed.) Vlfrd och frsrjning, pp. 171206. Stockholm: Fritzes.SCB (1985) Socialbidrag under 1983. rebro: Statistics Sweden.

SCB (1987) Socialbidrag under 1987. rebro: Statistics Sweden.Scott, J. (1996) Stratification and Power; Structures of Class, Status and Command. Cambridge: Polity Press.SoS (2005) Ekonomiskt bistnd rsstatistik, 2004, Socialstyrelsen, socialtjnst 2005: 7.Strandh, M. (1999) Ungdomsarbetslshet och ekonomisk marginalisering, in A. Gullberg and

M. Brjesson (eds) I vuxenlivets vntrum, pp. 13554. Ume: Bora.Torge, J. (1997) Inkomstutvecklingen 19751995, in L. Hll and J. Vogel (eds) Vfrd och ojmlikhet i

ett 20-rsperspektiv 19751995, pp. 12536. Stockholm: SCB.Weber, M. (1968) Economy and Society An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. New York: Bedminster Press.Westberg, A. (2004a) Livsfas eller generation? Ungas attityder till vlfrdsstatliga utgifter, Sociologisk

Forskning 3: 5573.Westberg, A. (2004b) Forever Young? Young Peoples Conception of Adulthood The Swedish Case,

Journal of Youth Studies 7: 3553.Whittington, L. A. and Peters, E. H. (1996) Economic Incentives for Financial and Residential Indepen-

dence, Demography 33: 8297.

Hallerd and Westberg: Incomes and Economic Hardship Among Swedish Youth

101

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ on March 6, 2014asj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/http://asj.sagepub.com/ -

8/12/2019 Acta Sociologica-2006-Hallerd-83-102

21/21

Vogel, J. (2002) Welfare Production, Poverty and Wealth: A Comparative and Longitudinal Perspective,in W. Glatzer (ed.) Rich and Poor. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Press.

Vogel, J. and Rbck, G. (2003) Materiell ojmlikhet i tids och internationellt perspektiv, in StatisticsSweden, Report No. 100, Vlfrd och ofrd p 90-talet. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrn.

Wyn, J. and White, R. (1997) Rethinking Youth. London: Sage.

Biographical Note: Bjrn Hallerd is Professor in the Department of Sociology, Ume University. Hisresearch interests include social stratification, distribution of economic resources and poverty.Address: Department of Sociology, Ume University, SE-901 87 Ume, Sweden.[email: bjorn.hallerod@ soc.umu.se]

Biographical Note: Annika Westberg obtained her PhD at Ume University in 2004. Her researchinterests mainly concern adolescence and young peoples transition into adulthood.Address: Department of Sociology, Ume University, SE-901 87 Ume, Sweden.

[email: annika. [email protected]]

Acta Sociologica 49(1)

![Acta Archeologica Carpathica Sygn - Uniwersytet …Acta Judaica Lodziensia Sygn. 26707 T. 1-2012 Acta Mediaevalia Sygn. 25881A Lublin 1973- [R.] 1 - 1973; [R.] 2 – 1974 Acta Militaria](https://static.fdocumenti.com/doc/165x107/5f2902d1c806b90be508467d/acta-archeologica-carpathica-sygn-uniwersytet-acta-judaica-lodziensia-sygn-26707.jpg)