69. Bernardo Bellotto, detto Canaletto Sabine Bendfeldt Il Mercato … · 2018. 4. 3. · 69....

Transcript of 69. Bernardo Bellotto, detto Canaletto Sabine Bendfeldt Il Mercato … · 2018. 4. 3. · 69....

-

69. Bernardo Bellotto, detto Canaletto(Venezia, 1722 - Varsavia, 1780)Il Mercato nuovo di Dresda visto dallo Jüdenhof 1749 (?)

tecnica/materiali olio su tela

dimensioni 136 × 236 cm

provenienza collezioni del principe elettore Federico Augusto II di Sassonia

collocazione Dresda, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Galleria n. 610)

scheda storico-artistica Andreas Henning (curatore dei dipinti italiani nelle Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister)

relazione di restauro Sabine Bendfeldt

restauro Sabine Bendfeldt (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Diplom Restauratorin, Gemälderestaurierung)

con la direzione di Marlies Giebe (direttrice del gabinetto di restauro dei quadri, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden) e di Andreas Henning (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister)

Bernardo Bellotto, known as Canaletto(Venice, 1722–Warsaw, 1780)The New Market of Dresden Seen from the Jüdenhof1749 (?)

technique/ material oil on canvas

dimensions 136 × 236 cm

provenance collection of Prince-Elector Frederick Augustus II of Saxony

current location Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Gallery no. 610)

critical note Andreas Henning (curator of Italian painting at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister)

restoration report Sabine Bendfeldt

restoration Sabine Bendfeldt (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Diplom Restauratorin, Gemälderestaurierung)

chief restorer: Marlies Giebe (Head of the Conservation Department for Paintings at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden); Andreas Henning (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meisters)

Bernardo Bellotto (genannt Canaletto) (Venedig 1722 - 1780 Warschau)Der Neumarkt in Dresden vom Jüdenhofe aus 1749 (?)

Material/Technik Öl auf Leinwand

Abmessungen 136 × 236 cm

Herkunft Sammlung des sächsischen Kurfürsten Friedrich August II

Standort Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Galerie Nr. 610)

Kunsthistorische Notiz Andreas Henning (Kurator für italienische Malerei der Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister)

Restaurierungsbericht Sabine Bendfeldt

Restaurierung Sabine Bendfeldt (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Diplom Restauratorin, Gemälderestaurierung)

Projectleiter: Leiterin der Gemälde-Restaurierung der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden: Marlies Giebe; Andreas Henning (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister)

-

Dopo il restauroThe painting following the conservation treatmentDas Gemälde nach der Restaurierung

-

Scheda storico-artistica

Bellotto e la veduta del Mercato nuo-vo di Dresda con la prima Gemäl-degalerieLe vedute di Bernardo Bellotto (detto Canaletto) – questo il no-me completo con cui era cono-sciuto l’artista – ci permettono di compiere un vero e proprio viag-gio a ritroso nel tempo, catturati dall’eccezionale qualità artistica e dall’accurata testimonianza storica delle opere. Dalla mano di Bellotto provengono infatti le più impor-tanti rappresentazioni che hanno disegnato nei secoli – come ancora avviene – l’immagine di Dresda co-me residenza augustea. Tra queste si annovera in primo luogo Dresda dalla riva destra dell’Elba oltre il ponte di Augusto (Kozakiewicz 1972, 2, p. 115 sgg., n. 146; Ber-nardo Bellotto 2011, p. 105, n. 2; cfr. anche Bendfeldt 2011; Hen-ning 2011a), ma anche il dipinto con la veduta del Mercato nuovo è di assoluta importanza. Oggetto di recente restauro con il genero-so sostegno di Intesa Sanpaolo, quest’ultimo raffigura infatti non solo la Frauenkirche nel cuore di

Dresda, ma anche uno dei mag-giori progetti architettonici voluti dal principe elettore Federico Au-gusto II di Sassonia, cioè la nuova Gemäldegalerie. Un elemento di non poca rilevanza, che determi-na il particolare valore di questa tela rispetto al ciclo delle vedute di Dresda dell’artista, è costituito dalla presenza del sovrano stesso: la piazza del Mercato nuovo è infatti attraversata dalla carrozza reale.I dipinti di Bellotto ritraggono un’epoca che fu determinata da due figure: Federico Augusto I, detto Augusto il Forte (1670-1733), e suo figlio Federico Augu-sto II (1696-1763), entrambi prin-cipi elettori di Sassonia e sovrani di Polonia. In particolare per una città come Dresda questi dipinti sono veri e propri latori del passa-to, perché non fu solo la devastan-te distruzione della città durante la Seconda guerra mondiale, ma già prima anche la guerra dei Sette anni, che scoppiò proprio men-tre Bellotto si trovava a Dresda, a marcare il territorio con le tracce dei conflitti. Tanto più importanti risultano le vedute dipinte da Bel-lotto, che ci riportano in un tempo

passato autenticamente e vivida-mente rappresentato.

Bellotto e il vedutismoBellotto fu apprendista pittore presso lo zio Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) il quale, sebbene il genere si fosse affermato in Italia solo da poco, era considerato il più noto vedutista del suo tempo. L’ul-timo scorcio del Medioevo aveva già registrato la comparsa, seppu-re sporadica, di vedute cittadine sullo sfondo di dipinti e affreschi, ciononostante, a sud delle Alpi, la città in quanto tale non fu ogget-to di rappresentazione autonomo né durante il Rinascimento né in epoca barocca. Uno scenario mol-to diverso, invece, si profilò a nord delle Alpi, dove in particolare nella pittura olandese del Seicento, pae-saggi cittadini e scorci di quartiere conquistarono sempre maggiore popolarità. Fu proprio un artista olandese originario dei dintorni di Utrecht, Gaspar van Wittel, a dipingere nel 1680 le prime ve-dute di Roma, mentre la prima veduta di Venezia a noi giunta di questo artista è datata 1697 (Ma-drid, Museo del Prado). Gli arti-

sti della Serenissima adottarono il vedutismo: se Luca Carlevarijs fu il primo a dedicarsi quasi esclusi-vamente a inquadrature veneziane, Canaletto, di una generazione più giovane, avrebbe presto dominato il mercato. È probabile che Bel-lotto abbia iniziato a frequentare come apprendista la bottega ve-neziana dello zio intorno al 1735; certo è che nel 1738, a sedici anni, venne accolto nella Fraglia dei pit-tori veneziani. All’inizio degli anni Quaranta del Settecento Bellotto intraprese una serie di viaggi di studio; prima nei dintorni di Ve-nezia e di Parma, in seguito anche a Firenze, Lucca e Roma, infine in Lombardia. Un importante tram-polino di lancio per la sua carriera fu l’incarico, conferitogli da Carlo Emanuele III di Savoia nel 1745, di dipingere alcune vedute di To-rino, ma si deve riconoscere che la maturazione di Bellotto si sarebbe completata in epoche successive, presso diverse corti europee.

Bellotto a DresdaSolo due anni dopo la committen-za da parte di Carlo Emanuele III, nel 1747, Bellotto lasciò Venezia per trasferirsi a Dresda (per Bel-lotto a Dresda cfr. tra l’altro Wal-ther 1995; Rizzi 1996, p. 28 sgg.; Weber 2004; Henning 2011a; Henning 2011b; Wagener 2014, p. 121 sgg.). Fu presumibilmente in luglio che si mise in viaggio, accompagnato dalla moglie, dal figlioletto di cinque anni, Lorenzo, e dal servo Francesco, detto Checo. Non avrebbe mai più rimesso pie-de nella sua città natale, perché la sua carriera di pittore si sarebbe poi svolta a Dresda, Vienna, Monaco e Varsavia. Dresda era al tempo una delle corti d’Europa più attraenti dal punto di vista artistico. Venezia, d’altro canto, era il punto di riferimento culturale più prestigioso (cfr. Vene-dig - Dresden 2010). Già Augusto il Forte, padre del principe elettore in carica, aveva invitato a Dresda cantanti, musicisti, librettisti, sce-nografi e artisti della Serenissima, tra i quali i pittori Giovanni An-

Prima del restauroThe painting prior to the conservation treatmentDas Gemälde im Zustand vor der Restaurierung

-

tonio Pellegrini e Gaspare Diziani. Erano stati invitati perfino artigia-ni in grado di costruire le gondole, affinché il fiume sassone potesse sembrare una replica del Canal Grande. Anche la fisionomia della città fu disegnata traendo ispirazio-ne da Venezia: come testimoniano le vedute di Bellotto, la cupola del-la chiesa veneziana di Santa Maria della Salute influenzò il progetto della Frauenkirche, e anche il pon-te sull’Elba fu considerato come un ponte di Rialto in territorio sasso-ne. La vitalità della corte di Federi-co Augusto II – con i suoi ingenti investimenti nelle arti – dovette risultare estremamente allettante per Bellotto, che a quel punto ave-va terminato il suo apprendistato e trovato il suo stile. Se confrontate con le opere dei pittori residenti a Dresda, risulta evidente che l’approccio artistico e concettuale delle vedute di Bellotto è del tutto diverso. Tra l’altro, nel 1748 Bellotto fu nominato pittore di corte ed è significativo il fatto che acquisì subito una posizione di rilievo, considerando che il suo compenso annuo (1750 talleri), se paragonato a quello dei colleghi, era decisamente alto. In occasione della nomina, in aggiunta, l’artista ricevette una tabacchiera incasto-nata di pietre preziose che conte-neva trecento luigi d’oro. Il rango di Bellotto presso la corte di Dresda è documentato anche dai padrini che nel corso degli anni seguenti si proposero per il battesimo delle sue quattro figlie: il primo ministro conte Von Brühl e consorte, il prin-cipe elettore Federico Augusto II e Maria Giuseppa, il principe eredi-tario Federico Cristiano e Maria Antonia, come pure il principe Franz Xaver e la principessa Maria Christina.Come pittore di corte Bellotto lavorò soprattutto per il principe elettore di Sassonia Federico Au-gusto II. Per questo sovrano venne realizzata la prima versione delle vedute di Dresda e dintorni. Le vedute adottavano solitamente un formato di rappresentanza di rile-vanti dimensioni (circa 132 × 230

cm) che Bellotto aveva già utilizza-to a Verona nel 1745-1746. Curio-samente, l’artista realizzò comun-que per il primo ministro, il conte Von Brühl, una replica autografa delle vedute dipinte per il sovra-no, con le stesse dimensioni degli originali (la replica della veduta del Mercato nuovo con la Gemäldega-lerie che Bellotto realizzò per Von Brühl è custodita presso l’Ermita-ge, a San Pietroburgo; cfr. Koza-kiewicz 1972, 2, p. 132, n. 168; Bernardo Bellotto 2005, p. 91 sgg., n. 11; Canaletto. Bernardo Bellotto 2014, p. 232 sgg., n. 41; Bellotto e Canaletto 2016, p. 200 sgg., n. 68). Il dipinto qui esposto risale al pri-mo soggiorno a Dresda di Bellotto e appartiene alla serie del principe elettore Federico Augusto II. Nei primi undici anni trascorsi nella città sull’Elba, il pittore realizzò per il principe elettore quattordici vedute di Dresda e undici di Pirna, città situata a diversi chilometri a sud-est di Dresda, lungo l’Elba, e che fu presidiata da una guarnigio-ne. Poiché Bellotto replicò, firman-

dole di propria mano, ventuno di queste opere per Von Brühl (nello stesso formato), è presumibile che l’artista fosse in grado di completa-re un dipinto ogni tre mesi. Oltre a queste tele, nel medesimo perio-do Bellotto realizzò una serie di ulteriori repliche per committenti privati e le incisioni su rame delle sue vedute, destinate a mercato più ampio, furono riprodotte in svaria-te copie. È indubbio che Bellotto abbia rea-lizzato le vedute di Dresda e dintor-ni secondo un programma preciso. Purtroppo a tutt’oggi non esistono fonti note in grado di appurare le destinazioni del ciclo. Ipotesi vero-simili potrebbero includere il Ca-stello di Dresda, che era residenza reale, come pure altri castelli come quello di Hubertusburg e quello di Moritzburg. È altrettanto pos-sibile, comunque, che le vedute di Bellotto dovessero essere collocate nella residenza di Federico Augu-sto II a Varsavia (come re Augusto III di Polonia). L’ipotesi che queste vedute siano state concepite per

essere esposte in coppie deriva uni-camente dalle opere stesse (Weber 2004); di conseguenza, si può pre-sumere che il pendant del dipinto qui esposto sia Il Mercato nuovo di Dresda visto dalla Moritzstrasse (Kozakiewicz 1972, 2, p. 135, n. 170; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, p. 111, n. 8) – la stessa piazza, quindi, grazie ai due dipinti viene rappre-sentata da due punti di osservazio-ne quasi diametralmente opposti.Oltre alle già menzionate vedute di Dresda e Pirna, Bellotto realizzò anche cinque vedute della fortez-za di Königstein. Non ci è noto se in origine fossero state pianificate ulteriori vedute di altre residenze di rappresentanza della casata rea-le, come ad esempio Moritzburg, Pillnitz o il castello di caccia di Hubertusburg. È immaginabile che Bellotto non poté terminare il suo ciclo di vedute finché si trovava in Sassonia, perché lo scoppio nel 1756 della guerra dei Sette anni tra Prussia e Austria mise fine anche a questo suo progetto. Negli anni se-guenti gli incarichi si fecero preca-

Bernardo Bellotto, Dresda dalla riva destra dell’Elba oltre il ponte di Augusto, 1748, olio su tela, 133 × 237 cm, Dresda, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Galleria n. 606)Bernardo Bellotto, Dresden from the Right Bank of the Elbe, below the Augustus Bridge, 1748, oil on canvas, 133 × 237 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Gallery no. 606)Bernardo Bellotto, Dresden vom rechten Elbufer unterhalb der Augustusbrücke, 1748, Öl auf Leinwand, 133 × 237 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, (Galerie Nr. 606)

-

ri, di conseguenza l’artista si spostò presso due sovrani legati da stretti vincoli di parentela con il principe elettore di Sassonia: realizzò una serie completa di vedute sia pres-so la corte dell’imperatrice Maria Teresa, a Vienna (dove giunse nel 1759), sia due anni dopo presso la corte del principe elettore Massi-miliano III Giuseppe di Baviera, a Monaco. Alla fine del 1761 Bellotto fece ritorno a Dresda. Durante questo secondo soggiorno nella città sas-sone l’artista visse in condizioni notevolmente critiche. Quando, dopo la fine della guerra dei Set-te anni, nel 1763, morirono i suoi due maggiori mecenati, Federico Augusto II e il primo ministro Von Brühl, Bellotto dovette guardarsi intorno alla ricerca di nuove possi-bilità e fonti di guadagno. A questo periodo risale la produzione di alle-gorie e capricci. Nel 1764 l’artista ottenne un posto alla Kunstakade-mie di Dresda, l’Accademia di belle arti al tempo di recente fondazio-ne, tuttavia con un incarico di se-

cond’ordine, nello specifico quello di insegnante nei corsi preparatori di prospettiva destinati agli studen-ti di pittura paesaggistica e archi-tettura. Il tempo del Rococò augu-steo era ormai irrevocabilmente un ricordo del passato. Verso la fine del 1766 Bellotto chiese un conge-do di nove mesi per recarsi a San Pietroburgo, con l’intenzione di cercare un nuovo impiego presso la corte di Caterina II. Durante il viaggio fece però tappa a Varsavia, dove incontrò un nuovo mecenate, il re di Polonia Stanislao II Augusto Poniatwoski. Nominato pittore di corte nel 1768, fino al termine del-la sua vita Bellotto lavorò a Varsa-via, dove morì il 17 ottobre 1780.

La veduta del Mercato nuovo con la GemäldegalerieQuella qui esposta è la prima veduta di uno scorcio del cuore di Dresda realizzata da Bellotto. Il punto di vi-sta adottato dall’artista, rivolto ver-so est, inquadra la piazza del Mer-cato nuovo, che già nella seconda metà del XVI secolo era diventata

uno dei più importanti fulcri eco-nomici della città. Il profilo della veduta è tracciato da un imponente edificio eretto da George Bähr tra il 1726 e il 1743: la Frauenkirche, che si staglia con una cupola alta 95 metri. Altrettanto maestosa lungo il lato sinistro del dipinto si impo-ne, con la sua doppia scalinata, la Gemäldegalerie. Nei pressi della Frauenkirche, sempre sulla sinistra della chiesa, sono visibili residenze borghesi affiancate, mentre sul la-to destro dell’opera campeggia la Altstädter Wache, l’antico posto di guardia della città vecchia costruito nel 1715, quando a Dresda erano ancora di stanza due reggimenti. Lungo il margine estremo di destra è inoltre riconoscibile l’antico ma-gazzino del Gewandhaus, eretto da Paul Buchner nel 1591; nell’edificio tenevano i loro banchi i fabbrican-ti di tessuti, i macellai e i calzolai, mentre al piano superiore si riuni-vano gli stati provinciali (Landstän-de) e venivano organizzate rappre-sentazioni teatrali e feste.La collocazione del Gewandhaus

nella compagine compositiva del dipinto è un esempio della libertà artistica di Bellotto, del suo potersi permettere, all’occorrenza, uno sco-stamento dai dati topografici. L’arti-sta infatti spinge l’edificio fuori dal dipinto, con un ampio spostamento verso destra, così ampio da lasciar intravedere in fondo, sempre a de-stra, la Pirnaische Gasse, oggi Lan-dhausstraße (riguardo alla tecnica compositiva di Bellotto cfr. Schütz 2005; Groh 2011). In realtà, dal suo punto di osservazione Bellotto non avrebbe potuto allungare lo sguardo in questa via; di fatto, il Gewandhaus avrebbe addirittura coperto una parte della Altstädter Wache. Ma per conferire maggiore profondità alla piazza e in questo modo creare un palcoscenico più spazioso per l’arrivo della carrozza reale, Bellotto modificò la realtà in favore della persuasività pittorica. L’efficacia della composizione sul piano estetico era quindi per l’artista più importante della riproduzione asettica dell’assetto urbano.In questo senso è interessante anche il fatto che il pittore abbia realizzato questa veduta come dipinto storico (riguardo alla veduta come pittura storica cfr. il recente Kerber 2017). L’intenzione non era comunque quella di riferirsi a un evento con-creto, bensì di alludere alla presenza del principe elettore di Sassonia: infatti, arrivando dalla Pirnaische Gasse, la carrozza di gala della casa-ta reale, tirata da sei cavalli bianchi, attraversa la piazza accompagnata da cavalieri e da altre carrozze. Nella carrozza siede Federico Augusto II, e per questa ragione il dipinto ritrae soldati appostati davanti all’edificio dell’Altstädter Wache. Potrebbe non essere un caso che il principe elettore sia diretto verso la Gemäl-degalerie; il collegamento sottinteso da Bellotto tra Federico Augusto II e la pinacoteca non derivava infat-ti semplicemente dalle aspettative dell’artista veneziano. Piuttosto qui trova espressione programmatica l’importanza della Gemäldegalerie, che svolgeva un ruolo di rappre-sentanza cruciale per la corte. Solo pochi anni prima, nel 1746, la pi-

Bernardo Bellotto, Il Mercato nuovo a Dresda visto dalla Moritzstraße, 1750 ca, olio su tela, 135 × 237 cm, Dresda, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Galleria n. 613)Bernardo Bellotto, The New Market of Dresden Seen from the Moritzstraße, ca. 1750, oil on canvas, 135 × 237 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Gallery no. 613)Bernardo Bellotto, Der Neumarkt in Dresden von der Moritzstraße aus, um 1750, Öl auf Leinwand, 135 × 237 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Galerie Nr. 613)

-

nacoteca aveva guadagnato un pro-filo di livello europeo acquisendo cento capolavori provenienti dalla Galleria Estense del duca di Mode-na Francesco III d’Este. L’edificio è da annoverarsi tra le più signifi-cative architetture rinascimentali della città; fatto costruire da Paul Buchner tra il 1586 e il 1591 per ospitare le scuderie e le carrozze di rappresentanza, durante il regno del principe elettore Federico Augusto II, e precisamente tra il 1744 e il 1746, era stato trasformato da Jo-hann Christian Knöffel in una pi-nacoteca che era andata a occupare il primo piano, definito da una fac-ciata scandita da grandi finestre con archi a tutto sesto. Qui la collezione di dipinti, il cui nucleo principale risaliva alla Kunstkammer allestita nel 1560, trovava per la prima volta una sistemazione di livello adegua-to. La rappresentatività di questo museo può essere pienamente in-tesa considerando che nessun altro sovrano collezionò dipinti in ma-niera così sistematica e competente come Federico Augusto II. Quindi il fatto che Bellotto abbia inserito in questa veduta il suo committente è tutt’altro che una casualità. In un certo qual modo, l’artista veneziano rese omaggio alla collezione di que-sto principe elettore – il suo occhio esperto aveva sicuramente valutato la qualità della raccolta, che aveva come fulcro la pittura italiana.La veduta con Il Mercato nuovo di Dresda visto dallo Jüdenhof fu verosi-milmente realizzata nel 1749: que-sto, perlomeno, è l’anno di datazio-ne delle incisioni che la riproducono (Kozakiewicz 1972, 2, p. 132 sgg., n. 169; cfr. anche Morosini 1999, p. 88 sgg., n. 13; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, p. 124, n. 25; Succi 2011, p. 127 sgg., n. 43), quindi il dipinto potrebbe risalire al 1749 o all’anno precedente. La prima registrazione dell’opera fu inclusa in un inventa-rio oggi perduto, ma il numero che le fu attribuito ci permette di risalire a un ulteriore inventario, databile al 1748-1749 (Weber 2004, p. 100, appendice II). Comunque sia, se Bellotto aveva sperato che le sue ve-dute potessero essere esposte nella

Gemäldegalerie inclusa nel dipinto, rimase deluso, perché quasi tutte le sue vedute, compresa questa con il Mercato nuovo, furono esposte solo nel 1834 in uno spazio apposito, la Galerie vaterländischer Prospekte, cioè in una galleria che ospitava ve-dute locali (riguardo alla storia delle collezioni dei dipinti di Bellotto a Dresda cfr. Henning 2011a, p. 16 sgg.). Con le altre vedute cittadine dell’autore, la tela fu poi trasferita nel 1855 nella nuova Gemälde-galerie am Zwinger progettata da Gottfried Semper, dove occupa da allora una posizione di rilievo all’in-terno dell’esposizione permanente. Questa veduta costituisce un pun-to culminante dell’attività creativa dell’artista, e lo stesso si può dire delle altre opere realizzate durante il suo primo soggiorno a Dresda. Cer-tamente non può essere nemmeno paragonata a quelle immagini che riproducono fotograficamente la realtà, in scala 1:1, talvolta scattate con un cellulare. La tela di Bellotto è un’opera d’arte, e artistici sono gli strumenti con cui è stata creata. Nel-la veduta sono coniugate in modo assolutamente originale caratteristi-che che permettono all’osservatore di sentirsi partecipe, con la massima naturalezza, della vita di quell’epoca passata: la precisione del dettaglio architettonico, la vivida descrizio-ne del quotidiano, una regia della luce ricca di sfumature. Lo scrupo-loso restauro eseguito tra il 2016 e il 2018 nel laboratorio di restauro delle Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden ha reso nuovamente perce-pibili gli alti valori estetici di un’o-pera in grado di suggestionare in-tensamente i visitatori. Per la prima volta, grazie alla mostra Restituzioni a Torino, questa importante veduta viene esposta al pubblico.

BibliografiaKozakiewicz 1972, 2, p. 132 sgg., n. 167; Walther 1995, p. 42 sgg., fig. 10; Bernardo Bellotto 2001, p. 167 sgg., n. 46; Weber 2004, p. 88, fig. 11; Wunschbilder 2009, p. 152 sgg., n. 3; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, p. 110, n. 177.

English versionCritical Note

Bellotto and the View of the New Market of Dresden with the First GemäldegalerieWith his views, the artist Bernardo Bellotto genannt (known as) Cana-letto – this the name by which he was known in Dresden – takes us on a journey back in time. By vir-tue of their extraordinary artistic quality and historical accuracy, Bel-lotto’s paintings are among the most poignant representations responsible for having shaped Dresden’s past and present identity as a royal city.

Most notable among these works is certainly Dresden from the Right Bank of the Elbe, below the Augus-tus Bridge (KozaKiewicz 1972, 2, 115ff., n. 146; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, 105, n. 2; see also Bendfeldt 2011; Henning 2011a) and also the remarkable view of Dresden’s New Market. The latter painting, which has been recently restored thanks to Banca Intesa Sanpaolo’s generous support, depicts not only the very central Frauenkirche, but also one of the greatest architectur-al projects commissioned by Elector Frederick Augustus II of Saxony: the new Gemäldegalerie. An important

Pietro Antonio Graf Rotari, Il principe elettore Federico Augusto II di Sassonia, come Augusto III re di Polonia, post 1755, olio su tela, 108 × 86 cm, Dresda, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Inventario n. 99/77)Pietro Antonio Graf Rotari, Elector Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, as Augustus III King of Poland, post 1755, oil on canvas, 108 × 86 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Inventary no. 99/77)Pietro Antonio Graf Rotari, Kurfürst Friedrich August II. von Sachsen, als polnischer König August III, post 1755, Öl auf Leinwand, 108 × 86 cm, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Inventar Nr. 99/77)

-

element of this painting by Bellotto, which makes it stand out among all his other views of Dresden, is the pres-ence of the sovereign, signified by the royal carriage we see crossing the New Market square. By portraying the age of Frederick Augustus I, known as Augustus the Strong (1670–1733), and of his son Frederick Augustus II (1696–1763), both Electors of Saxony and Kings of Poland, Bellotto’s paintings are docu-ments of the greatest importance for Dresden – a city that suffered dev-astating damage during World War II, and prior to that, was scarred by the Seven Years’ War, a conflict that broke out in Bellotto’s time – two tragic events that make the Venetian painter’s works all the more import-ant, thanks to their accurate and viv-id representation of the past capable of carrying us back in time.

Bellotto and VedutismBellotto carried out his apprentice-ship with his uncle Canaletto (whose real name was Giovanni Antonio Canal), the artist who had affirmed himself as the most prominent veduta painter of his time, even though this genre was still fairly recent in Italy. City views had made occasional ap-pearances in late medieval painting and fresco backgrounds, but south of the Alps throughout the Renaissance and the Baroque era city views had never been considered as a subject per se. North of the Alps, however, things went rather differently with cityscapes and street views becoming increasingly popular artistic sub-jects, as effectively attested by seven-teenth-century Dutch painting. It was in fact a Dutch painter, born not far from Utrecht – Caspar van Wittel –, who painted the first views of Rome in 1680, and completed his first view of Venice (today at the Prado, Madrid) in 1697. Venetian painters soon embraced the genre of Vedutism: Luca Carlevarijs was the first to concentrate almost his entire production on Venetian views, al-though the market was soon taken by a painter of the following gen-eration: Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto. It is likely that

Bellotto started his apprenticeship at his uncle’s workshop in Venice around 1735, and we know that in 1738, aged sixteen, he was admitted to the Fraglia, the guild of Venetian paint-ers. In the early 1740s, Bellotto em-barked on a number of study trips, first around Venice and in Parma, and then in Florence, Lucca, Rome, and lastly in Lombardy. An import-ant milestone in his career was when in 1745 Charles Emmanuel III of Savoy commissioned him some views of Turin. Bellotto’s full artistic matu-rity however came later, while work-ing at the courts of Europe.

Bellotto in DresdenIn 1747, only two years after Charles Emmanuel III of Savoy’s commis-sion, Bellotto left Venice and moved to Dresden (on Bellotto in Dresden see also waltHer 1995; rizzi 1996, 28ff.; weBer 2004; Henning 2011a; Henning 2011b; wage-ner 2014, 121ff.). He probably left in July, with his wife, his five-year-old son Lorenzo, and their servant Francesco, called Checo. Bellotto was never to return to his hometown. His artistic career was to lead him to the courts of Dresden, Vienna, Munich, and Warsaw.While Venice was the most prominent city in terms of culture, Dresden at the time was – artistically speaking – one of the most interesting courts in Europe (see Venedig – Dresden 2010). Already back in his day, Au-gustus the Strong, father of Elector Frederick Augustus II, had invited singers, composers, librettists, theat-rical scene painters, and artists from the Republic of Venice to come and work in Dresden. Among these artists were Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini and Gaspare Diziani, along with specialised gondola-builders who with their vessels were supposed to make the Saxon river resemble Ven-ice’s Grand Canal. Even the design of the city itself was inspired by Venice: as Bellotto’s views attest, the project for the Frauenkirche was influenced by the dome of Santa Maria della Sa-lute, and the bridge across the river Elbe was intended as a Saxon Rialto Bridge.

The vitality of the court of Frederick Augustus II – with its notable invest-ments in the arts – certainly proved very attractive to Bellotto who at that stage of his life had finished his ap-prenticeship and had found his own artistic voice. By comparing the works of other painters active in Dresden at the time with those of Bellotto, it is clear to see how different his artistic ap-proach and conceptual framework were. In Dresden Bellotto rapidly gained great prestige, and was ap-pointed court painter already in 1748 with a 1750-thalers yearly salary – a substantial amount com-pared to the income of his fellow contemporary artists. When named court painter, the artist even received a precious-stone-studded tobacco jar filled with three hundred Louis d’or. Bellotto’s level of prestige at the court of Dresden is also attested by the per-sonalities who offered to become god-fathers to his four daughters: Prime Minister Count von Brühl and his wife; the Elector Frederick Augustus II and Maria Josepha; the Electoral Prince Frederick Christian and Ma-ria Antonia, and also Prince Franz Xaver and Princess Maria Christina. As a court painter Bellotto mainly worked for Elector Frederick Augus-tus II of Saxony who commissioned the first version of the views of Dres-den and its surroundings. His views were usually conceived as prestigious large-size paintings (about 132 × 230 cm), a format Bellotto had al-ready used in Verona in 1745–46. Curiously, the artist made a signed and same-size replica of the views he painted for the sovereign even for Prime Minister Count von Brühl (the replica of the view of the New Market with the Gemäldegalerie that Bellotto painted for von Brühl is to-day kept at the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg; see KozaKiewicz 1972, 2, 132, n. 168; Bernardo Bellotto 2005,. 91ff., n. 11; Canaletto. Ber-nardo Bellotto 2014, 232ff., n. 41; Bellotto e Canaletto 2016, 200ff., n. 68).The painting here displayed was made during Bellotto’s first sojourn in Dresden and is part of the series

commissioned by Elector Frederick Augustus II. During the first eleven years in the city on the river Elbe, the Venetian painter made fourteen views of Dresden and eleven of Pir-na, a garrisoned city located a few kilometres south-east of Dresden on the river Elbe. Since Bellotto painted autographed replicas of twenty-one of these works for von Brühl (maintain-ing the original format), it is likely that the painter was able to com-plete a painting every three months. Besides these paintings, in this same period, Bellotto also produced a series of other replicas for private patrons as well as copper engravings of his views to make prints destined to meet the demand of a wider market. Bellotto clearly painted the views of Dresden and of its surroundings fol-lowing a precise work plan. Unfor-tunately, to date, no record has been found indicating for what location this series was intended. They might have been painted for the Dresden Castle where the royals resided, or for other residences such as the Hu-bertusburg and Moritzburg castles. Another possible destination for these works might have been Frederick Augustus’s residence in Warsaw (as king Augustus III of Poland). As the works themselves suggest, these views were probably meant to be displayed in pairs (Weber 2004) and the pen-dant of the painting presented here might possibly have been The New Market of Dresden Seen from the Moritzstraße (KozaKiewicz 1972, 2, 135, n. 170; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, 111, n. 8) depicting the same square from the opposite side.Besides the previously mentioned views of Dresden and Pirna, Bel-lotto also painted five views of the Königstein Fortress. We do not know if views of other royal residences, such as Moritzburg, Pillnitz, and the Hubertusburg hunting castle, were planned. It is plausible that Bellot-to was unable to finish his series of Saxon views because of the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War in 1756 be-tween Prussia and Austria, an event that put an end to this project. The following years commissions became scarcer and it was then that the artist

-

decided to move to the courts of two sovereigns closely related to the Elector of Saxony: Empress Maria Theresa in Vienna at whose court he arrived in 1759 painting a complete series of views, and Maximilian III Joseph of Bavaria in Munich where Bellotto arrived two years later.At the end of 1761 Bellotto returned to Dresden, but his second sojourn in the Saxon city was to be a critical time of his life: in 1763, at the end of the Seven Years’ War, two of his major patrons – Frederick Augustus II and Prime Minister von Brühl – died, putting the artist in the position of having to find new sources of income. His allegorical paintings and capricci date to this period. In 1764 the artist eventually secured himself a position at the Kunstakademie, the recently founded Fine Art Academy of Dres-den. His role there however was not very prestigious, since he held perspec-tive preparatory classes for landscape and architecture painting students.

The Augustan Rococo season was a thing of the past, and towards the end of 1766 Bellotto asked for a nine-month leave to travel to Saint Peters-burg in the hope of being employed at the court of Catherine II. But on his way there he stopped in Warsaw where he met a new art patron, King of Poland Stanisław II August Poni-atowski. Appointed court painter in 1768, Bellotto worked in Warsaw until his death, 17 October 1780.

The View of the New Market with the GemäldegalerieThe view on display is Bellotto’s first depiction of a part of Dresden’s inner city. The painter here chose to look eastwards, capturing the New Mar-ket square that since the second half of the sixteenth century had been one of the most important economic cen-tres of the city. The skyline is marked by the imposing Frauenkirche built by George Bähr between 1726 and 1743 with its 95-metre-high dome.

Equally imposing on the left is the Gemäldegalerie with its double-ramp staircase. By the Frauenkirche, on the left, is a row of middle-class houses, while on the right is the Altstädter Wache, the 1715 observation post of the old city built for the two regi-ments that used to station in Dresden. Along the far right margin is the old Gewandhaus warehouse, erected by Paul Buchner in 1591; the building was where textile manufacturers, butchers, and shoemakers sold their products, while the upper floor was used for the meetings of the provin-cial states (Landstände), theatre rep-resentations, and celebrations.The position of the Gewandhaus within the composition is an example of Bellotto’s creative freedom, which allowed him to move away from strict topographical description. The artist in fact pushed the building out of the painting moving it to the far right in order to reveal Pirnaische Gasse, to-day’s Landhausstraße (On Bellotto’s

compositional technique see ScHütz 2005; groH 2011), which we can see in the distance. From his observation point, however, Bellotto could not have seen as far as that street. The Ge-wandhaus would even have covered a part of the Altstädter Wache. But to add further depth to the square and therefore create a more spacious setting for the arrival of the royal coach, Bel-lotto modified reality to achieve great-er pictorial effectiveness. Composition and aesthetic outcome were therefore more important than a rigorous re-production of the urban setting. In this respect it is also interesting to note how the painter conceived this view as a historical painting (on this view as a historical painting see the recent KerBer 2017). His purpose however was not to refer to a specific event, but to allude to the presence of the Elector of Saxony: arriving from Pirnaische Gasse, the royal coach drawn by six white horses crosses the square accompanied by horsemen

Dopo il restauro, particolareThe painting following the conservation treatment, detailDas Gemälde im Zustand nach der Restaurierung, Detail

-

and other coaches. Inside the coach sits Frederick Augustus II, and for this reason the painting depicts soldiers stationing before the Altstädter Wa-che building. The fact that the Elec-tor is heading to the Gemäldegalerie might be intentional; the connection between Frederick Augustus II and the gallery that Bellotto alludes to is not only a reflection of the Venetian artist’s expectations. This painting in fact also expresses the programmatic importance of the Gemäldegalerie,

an institution that had a crucial role in adding prestige to the court. On-ly a few years earlier, in 1746, the picture gallery had risen to European prominence through the acquisition of one hundred masterpieces from the Estense Gallery of Francesco III d’Es-te, Duke of Modena. The building is among the most no-table Renaissance architectures of the city; commissioned by Paul Buchner between 1586 and 1591 to serve as stables and royal coach deposit, be-

tween 1744 and 1746, during the reign of Elector Frederick Augustus II, it was transformed into a picture gallery. Designed by Johann Chris-tian Knöffel, the gallery occupied the first floor, with a façade defined by large round-arch windows: here, for the first time, the painting collection whose main nucleus had been set up in 1560 in the Kunstkammer found a suitable setting. The great cultural import of this museum can be fully grasped considering that no other sov-

ereign collected paintings with such method and competence as Frederick Augustus II. So the fact that Bellotto included his patron in this view is no coincidence at all: by doing so the Ve-netian artist was paying homage to the collection of the Elector having certainly understood the value of this fine selection greatly based on Italian painting. The New Market of Dresden Seen from the Jüdenhof was probably painted in 1749: this is in any case the date that appears on the engrav-ings (KozaKiewicz 1972, 2, 132ff., n. 169; see also MoroSini 1999, 88 sgg., n. 13; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, 124, n. 25; Succi 2011, 127ff., n. 43) that reproduce the view, indi-cating that the painting could date to 1749 or the previous year. The paint-ing was first recorded in an inventory that has been lost, but the number it was given relates the piece to another inventory dated 1748–49 (Weber 2004, 100, appendix II). In any case, if Bellotto ever hoped his views would be displayed in the Gemäldegalerie he depicted in his painting, he must have faced disappointment, since al-most all his views, including this one of the New Market square, were to be displayed only in 1834 at the Galerie vaterländischer Prospekte, a gallery specifically dedicated to local views (On the history of the collections of Bellotto’s paintings in Dresden, see Henning 2011a, 16ff.). In 1855 along with other city views by Bel-lotto, the painting was transferred to the new Gemäldegalerie am Zwinger designed by Gottfried Semper where it still proudly hangs as part of the museum’s permanent display.This view represents one of the high-points of the artist’s production, and the same can be said about the other works Bellotto made during his first sojourn in Dresden: a picture that shares nothing with those scale 1:1 photographic images – some of them even taken with a mobile phone. Bel-lotto’s view is an artwork created with artistic tools and techniques, clever-ly combining a number of qualities that allow viewers to feel naturally drawn into the life of the past: precise architectural details, fresh depictions

Dopo il restauro, particolareThe painting following the conservation treatment, detailDas Gemälde im Zustand nach der Restaurierung, Detail

-

of everyday life, and a knowing and nuanced light rendition. The atten-tive restoration carried out between 2016 and 2018 by the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden conser-vation department has made the high aesthetic values of this painting newly readable. For the first time this remarkable pic-ture is shown to the viewers, thanks to the current exhibition in Turin.

BibliographyKozaKiewicz 1972, vol. 2, 132ff., n. 167; waltHer 1995, 42ff., fig. 10; Bernardo Bellotto 2001, 167ff., n. 46; weBer 2004, 88, fig. 11; Wunschbilder 2009, 152ff., n. 3; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, 110, n. 177.

Deutsche VersionKunsthistorische Notiz

Bellottos Ansicht des Neumarkts mit der ersten Gemäldegalerie in DresdenDie Veduten von Bernardo Bellotto (genannt Canaletto) ermöglichen dem Betrachter eine regelrechte Zeit-reise. Dank ihrer herausragenden künstlerischen Qualität und ho-hen historischen Präzision laden sie in eine vergangene Epoche ein. So stammen von der Hand Bellottos die wichtigsten Ansichten, die bis heute unsere Vorstellung von dem Aussehen der augusteischen Residenzstadt prä-gen. Dazu zählt natürlich zu aller-erst „Dresden vom rechten Elbufer unterhalb der Augustusbrücke“ (Ko-zaKiewicz 1972, vol. 2, ss. 115 sgg., n. 146; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, s. 105, n. 2; Bendfeldt 2011; Henning 2011a). Von zentraler Bedeutung ist daneben aber auch das jüngst mit großzügiger Unterstützung der Intesa Sanpaolo restaurierte Gemäl-de mit der Ansicht des Neumarkts. Denn es zeigt nicht nur die Frau-enkirche im Zentrum von Dresden, sondern auch eines der wichtigsten Bauprojekte des sächsischen Kurfürs-ten Friedrich August II., nämlich die neue Gemäldegalerie. Die große Re-levanz, die dieses Gemälde für den Zyklus der Stadtansichten Bellottos einnahm, kommt nicht zuletzt da-rin zum Ausdruck, dass er selbst in der königlich-kurfürstlichen Kutsche über den Neumarkt fährt.Bellottos Gemälde erschließen eine Epoche, die von Friedrich August I., genannt August der Starke (1670-1733), und seinem Sohn Friedrich August II. (1696-1763) geprägt wurden - beide waren Kurfürsten von Sachsen und Könige in Polen. Gerade für eine Stadt wie Dresden sind diese Gemälde echte Botschafter der Ver-gangenheit, denn nicht nur die um-fangreichen Zerstörung im Zweiten Weltkrieg, sondern schon der Sieben-jährige Krieg, der noch während Bel-lottos Aufenthalt in Dresden ausbrach, hinterließ seine martialischen Spuren. Umso wichtiger sind Bellottos gemalte Ansichten, die authentische Blicke in die Vergangenheit ermöglichen.

Bellotto und die VedutenmalereiBellotto wurde von seinem Onkel Canaletto, der eigentlich Giovanni Antonio Canal hieß, ausgebildet. Canaletto war damals der berühm-teste Vedutenmaler seiner Zeit. Dabei war die Vedutenmalerei in Italien eine noch recht junge Erfindung. Auch wenn schon im ausgehenden Mittelalter vereinzelt Stadtansichten als Hintergründe in Gemälden und Fresken auftauchten, so wurde südlich der Alpen die Stadt als solche weder in der Renaissance noch im Barock als eigenständiges Motiv für würdig erachtet. Ganz anders dagegen nörd-lich der Alpen, wo insbesondere in der holländischen Kunst des 17. Jahrhun-derts Stadtpanoramen und innerstäd-tische Darstellungen eine immer grö-ßere Popularität gewannen. So war es auch ein holländischer Künstler, und zwar der aus der Nähe von Utrecht

stammende Gaspar van Wittel, der um 1680 in Rom die ersten Veduten zu malen begann. Die früheste Ansicht von Venedig, die von diesem Künstler überliefert ist, datiert aus dem Jahr 1697 (Madrid, Museo del Prado). Einheimische Künstler der Serenissima griffen diese Gattung auf, wobei Luca Carlevarijs der erste war, der sich fast ausschließlich der Darstellung von Ve-nedig-Ansichten verschrieb. Doch der um eine Generation jüngere Canaletto sollte bald den Markt beherrschen.Um 1735 dürfte der junge Bellotto mit der Ausbildung in der Werkstatt seines Onkels in Venedig begonnen ha-ben. Gesichert ist, dass er 1738 – mit 16 Jahren – in die venezianische Gilde der Maler (Fraglia dei Pittori) aufge-nommen wurde. Anfang der 1740er Jahre unternahm Bellotto mehrere Studienreisen; zunächst in die Umge-bung von Venedig und Parma, dann

Dopo il restauro, particolareThe painting following the conservation treatment, detailDas Gemälde im Zustand nach der Restaurierung, Detail

-

auch nach Florenz, Lucca und Rom sowie schließlich in die Lombardei. Ein wichtiges Sprungbrett für seine Karriere war 1745 der Auftrag von König Carl Immanuel III., Veduten von Turin zu malen. Denn tatsäch-lich sollte sich Bellottos weitere Ent-wicklung an verschiedenen Höfen in Europa abspielen.

Bellotto in DresdenNur zwei Jahre später – 1747 – verließ Bellotto Venedig in Richtung Dresden (Zu Bellotto in Dresden siehe unter anderem waltHer 1995; rizzi 1996, ss. 28 sgg; weBer 2004; Henning

2011a; Henning 2011b; wagener 2014, ss. 121 sgg). Wahrscheinlich im Juli machte er sich gemeinsam mit seiner Frau, seinem fünfjährigen Sohn Lorenzo und dem Diener Francesco Checo in Venedig auf die Reise – er soll-te seine Geburtsstadt niemals wieder betreten. Dresden, Wien, München und Warschau wurden seine neuen Wirkungsorte.Dresden war damals einer der künst-lerisch anziehendsten Höfe in Euro-pa. Das große kulturelle Vorbild war Venedig (Venedig - Dresden 2010). Schon August der Starke, der Vater des amtierenden Kurfürsten, hatte Sänger,

Musiker, Librettisten, Bühnenbildner und Künstler aus der Serenissima an die Elbe holen lassen, darunter die Maler Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini und Gaspare Diziani. Selbst Gondel-bauer waren hier tätig, um den säch-sischen Fluss zu einem zweiten Canal Grande zu formen. Auch im Stadt-bild versuchte man sich an Venedig zu orientieren. Wie in Bellottos Veduten zu sehen, beeinflusste die Kuppel der venezianische Kirche Santa Maria de-lla Salute den Bau der Frauenkirche oder galt die Elbbrücke als sächsischer „Ponte di Rialto“. Die Dynamik des Hofes von Friedrich August II. mit sei-

nen großen Investitionen in die Künste muss für einen Maler wie Bellotto, der zum damaligen Zeitpunkt vollständig ausgebildet war und sein Stil gefunden hatte, sehr verlockend gewirkt haben.Im Vergleich zu den Gemälden der in Dresden ansässigen Künstler ist er-sichtlich, dass Bellotto seine Veduten mit einem ganz anderen konzeptuel-len und künstlerischen Ansatz schuf. 1748 wurde Bellotto zum Hofmaler ernannt. Signifikanterweise nahm er sofort eine herausragende Stellung ein, denn sein Gehalt von jährlich insge-samt 1750 Talern ist im Vergleich zu den Gehältern seiner Malerkollegen ausgesprochen hoch. Zudem wurde Bellotto bei seiner Ernennung eine mit Edelsteinen besetzte Tabakdose mit 300 Louisdor überreicht. Seinen Rang am Dresdener Hof dokumentiert sich auch in den Patenschaften, die sich im Laufe der folgenden Jahre bei der Tau-fe seiner vier Töchter zur Verfügung stellten: Premierminister Graf Brühl mit seiner Frau, Kurfürst Friedrich August II. und Maria Josepha, Kur-prinz Friedrich Christian und Maria Antonia sowie Pinz Franz Xaver und Prinzessin Maria Christina.Als Hofmaler arbeitete Bellotto vor allem für den sächsischen Kurfürs-ten Friedrich August II. Für diesen Herrscher entstand jeweils die erste Fassung der Ansichten von Dresden und Umgebung. Als Format wurde in der Regel das große, repräsentative Maß von circa 132 mal 230 Zenti-meter verwendet, das Bellotto bereits 1745/46 in Verona verwendet hatte. Interessanterweise schuf er aber auch für den Premierminister Graf Brühl eine eigenhändige Wiederholung der für den Herrscher gemalten Vedu-ten, und zwar in der gleichen Größe wie die Urfassung (Die Wiederho-lung der Ansicht vom Neumarkt mit der Gemäldegalerie, die Bellotto für Brühl schuf, befindet sich in Sankt Petersburg, Ermitage; KozaKiewicz 1972, vol. 2, s. 132, n. 168; Bernar-do Bellotto 2005, s. 91 ff., n. 11; Ca-naletto. Bernardo Bellotto 2014, ss. 232 ff., n. 41; Bellotto e Canaletto 2016, s. 200 f., n. 68). Das hier ausgestellte Gemälde stammt aus Bellottos erstem Dresdener Aufent-halt. Es gehört zur Serie des Kurfürsten

Dopo il restauro, particolareThe painting following the conservation treatment, detailDas Gemälde im Zustand nach der Restaurierung, Detail

-

Friedrich August II. In den ersten 11 Jahren an der Elbe schuf er für diesen Kurfürsten 14 Ansichten von Dresden und 11 von Pirna, einer Garnisonss-tadt einige Kilometer elbaufwärts ge-legen. Da er 21 dieser Werke für den Premierminister Heinrich Graf von Brühl in dem gleichen Bildformat eigenhändig wiederholte, muss der Künstler alle 12 Wochen solch eine gro-ße Leinwand vollendet haben. Davon abgesehen schuf er in dieser Zeit auch noch eine Reihe an Repliken für priva-te Auftraggeber und vervielfältigte sei-ne Veduten in Form von Kupferstichen für den großen Markt.Sicherlich lag Bellottos Veduten, die er von Dresden und der Umgebung anfertigte, ein genaues Programm zu-grunde. Leider ist bislang keine Quelle bekannt, die Aufschluss geben würde über den Ort, für den der Zyklus ge-schaffen wurde. In Frage könnten das Dresdener Residenzschloss, aber auch andere Schlösser wie Hubertusburg oder Moritzburg kommen. Ebenso könnten Bellottos Veduten aber auch für Warschau gedacht gewesen sein, dem Residenzort von Friedrich Au-gust II. (als König August III. in Po-len). Einzig die Werke selber geben einen gewissen Hinweis darauf, dass sie wahrscheinlich als Bildpaare kon-zipiert wurden (weBer 2004). So ist davon auszugehen, dass als Gegenstück zu dem hier ausgestellten Bild die An-

sicht „Der Neumarkt in Dresden von der Moritzstrasse aus“ konzipiert wur-de (KozaKiewicz 1972, vol. 2, s. 135, n. 170; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, s. 111, n. 8). Somit zeigt dieses Bildpaar den Neu-markt aus der Perspektive von zwei fast diametral gegenüberliegenden Standorten.Neben den schon genannten Ansichten von Dresden und Pirna schuf Bellotto auch fünf Veduten von der Festung Königsstein. Ob ursprünglich noch weitere Ansichten von herrschaftlichen Repräsentationsorten geplant waren, wie zum Beispiel Moritzburg, Pillnitz oder das Jagdschloss Hubertusburg, ist unbekannt. Es ist wohl davon auszu-gehen, dass Bellotto seinen Zyklus in Sachsen nicht vollenden konnte, denn mit dem Ausbruch des Siebenjährigen Krieges 1756 zwischen Preußen und Österreich endete auch seine Arbeit an den Veduten. Für Bellotto wurde in den folgenden Jahren die Auftragslage prekär, weshalb er in zwei Residenz-städte reiste, die verwandtschaftlich eng mit dem sächsischen Kurfürsten verbunden waren: 1759 fuhr Bellot-to nach Wien an den Hof der Kaise-rin Maria Theresia, von dort reiste er 1761 nach München zu Kurfürst Maximilian III. Joseph von Bayern. In beiden Orten schuf er eine ganze Reihe an Veduten.Ende 1761 kehrte Bellotto nach Dres-

den zurück. In diesem zweiten Dresd-ner Aufenthalt lebte der Künstler in einer äußerst angespannten Lage. Als nach dem Ende des Siebenjährigen Krieges 1763 seine beiden Hauptför-derer Friedrich August II. und Pre-mierminister Brühl starben, musste Bellotto sich nach neuen Einnahme-möglichkeiten umsehen. Vornehm-lich entstanden nun Allegorien und Capricci. 1764 erhielt er eine Stelle an der neugegründeten Dresdener Kunstakademie, jedoch wurde er nur in einer untergeordneten Funktion als Lehrer für Vorkurse in Perspektive für die Studenten der Landschaftsmalerei und Architektur angestellt. Die Zei-ten des augusteischen Rokoko waren unwiderruflich vorbei. Gegen Ende des Jahres 1766 bat Bellotto um ei-ne neunmonatige Beurlaubung, um nach St. Petersburg zu reisen. Er woll-te dort am Hofe von Katharinas II. nach einer neuen Anstellung suchen. Doch auf dem Weg dorthin machte er in Warschau Station, wo er in Gestalt des polnischen Königs Stanisław Au-gust Poniatwoski einen neuen Mäzen fand. 1768 zum Hofmaler ernannt, arbeitete Bellotto bis zum Ende seines Lebens in Warschau, wo der am 17. Oktober 1780 starb.

Bellottos Ansicht des Neumarkts mit der GemäldegalerieDie hier ausgestellte Vedute ist die

erste innerstädtische Ansicht, die Bel-lotto von Dresden schuf. Der Künstler blickt über den Neumarkt in Richtung Osten. Dieser Platz hatte sich seit Mit-te des 16. Jahrhunderts zu einem der wichtigsten wirtschaftlichen Zentren der Stadt entwickelt. Die Frauenkir-che, die George Bähr 1726 bis 1743 errichtete, bestimmt die Silhouette der Ansicht mit ihrem 95 Meter hohen Kuppel. Doch nicht weniger promi-nent steht am linken Bildrand die Gemäldegalerie mit ihrer doppelläufi-gen Treppe. Vor der Frauenkirche sieht man links eine Reihe an Bürgerhäu-sers, rechts die Altstädter Wache. Letz-tere wurde 1715 erbaut, da sich in Dresden dauerhaft zwei Regimenter aufhielten. Ganz am rechten Bildrand ist das alte Gewandhaus zu erkennen, das Paul Buchner 1591 errichtet hat-te. Hier hatten nicht nur die Tuchma-cher, Fleischer und Schuster ihre Ver-kaufsstände, sondern im Obergeschoß tagten auch die Landstände und es wurden Schauspielaufführungen und Feste veranstaltet. Die Art und Weise, wie Bellotto dieses Gewandhaus in das Bild hineinkomponierte, ist ein Bei-spiel für seine künstlerische Freiheit, von topographischen Gegebenheiten gegebenenfalls auch abweichen zu können. Denn der Künstler hat das Gewandhaus ganz weit nach rechts aus dem Bild herausgeschoben, und zwar so weit, bis er einen Durchblick

Dopo il restauro, particolareThe painting following the conservation treatment, detailDas Gemälde im Zustand nach der Restaurierung, Detail

-

nach rechts hinten in die Pirnaische Gasse (heute: Landhausstraße) er-reicht hatte (Zu Bellottos Komposi-tionstechnik s. ScHütz 2005; groH 2011). Eigentlich hätte Bellotto von seinem Standpunkt aus diese Straße nicht einsehen können. Tatsächlich hätte das Gewandhaus sogar einen Teil der Altstädter Wache verdeckt. Doch um dem Platz mehr Tiefe und damit der Ankunft der königlich-kur-fürstlichen Kutsche eine großzügigere Bühne zu verleihen, änderte Bellotto die Wirklichkeit zugunsten der gemal-ten Überzeugungskraft um. Wichtiger als die fantasielose Kopie der Realität war ihm hier die ästhetische Wirkung.Dabei ist zudem interessant, dass der Maler diese Vedute als Histori-engemälde angelegt hat (Zur Vedu-te als Historienmalerei siehe jüngst

KerBer 2017). Dabei ist allerdings kein konkretes geschichtliches Ereig-nis gemeint, sondern der Auftritt des sächsischen Kurfürsten. Denn aus der Pirnaischen Gasse kommend fährt die königlich-kurfürstliche Staatskarosse über den Platz, begleitet von Reitern und weiteren Kutschen. In der sechs-spännigen, von Schimmeln gezogenen Staatskarosse sitzt Kurfürst Friedrich August II. Aus diesem Grund haben die Soldaten vor der Altstädter Wache Stellung bezogen. Es dürfte kein Zufall sein, dass der Kurfürst hier in Rich-tung der Gemäldegalerie fährt. Denn die Nähe, die Bellotto hier zwischen Friedrich August II. und dessen Ge-mäldesammlung postuliert, entsprang nicht bloß einer Wunschvorstellung des venezianischen Künstlers. Viel-mehr kommt hier programmatisch die

Bedeutung der Gemäldegalerie zum Ausdruck, die eine zentrale Rolle in der höfischen Repräsentation spielte. Nur wenige Jahre zuvor, 1746, war sie durch den Ankauf von hundert Meis-terwerken aus der Galerie des Mode-neser Herzogs Francesco III. d’Este auf ein europäisches Niveau gehoben worden. Das Gebäude der Galerie, das von Paul Buchner ursprünglich 1586 bis 1591 als Stallgebäude für die re-präsentativen Pferde und Kutschen errichtet worden war und das zu den wichtigste Renaissancegebäuden der Stadt zählte, war unter dem sächsi-schen Kurfürsten Friedrich August II. 1744/46 von Johann Christian Knöffel zu einer Gemäldegalerie um-gebaut worden, die sich im ersten Stock hinter den großen Rundbogenfenstern befand. Hier fand die Sammlung an Gemälden, deren Grundstock auf die um 1560 eingerichtete Kunstkam-mer zurückgeht, erstmals einen ihrem Rang entsprechende Unterbringung. Die Bedeutung der Darstellung dieses Museums wird verständlich, wenn man sich klar macht, dass kein an-derer Herrscher so systematisch und kennerschaftlich Gemälde sammelte wie Friedrich August II. Dass Bellotto in dieser Vedute seinen Auftraggeber in Szene setzte, dürfte also alles ande-re als Zufall sein. Der venezianische Künstler erweist gewissermaßen der Gemäldegalerie dieses Herrschers seine Reverenz. Sein künstlerisch geschul-tes Auge wird gewusst haben, welche Qualität diese Sammlung – mit ihrem Schwerpunkt in der italienischen Ma-lerei – vereint. Die Vedute ist wahrscheinlich 1749 entstanden. Zumindest ist mit diesem Jahr Bellottos Grafik dieser Ansicht datiert (KozaKiewicz 1972, vol. 2, s. 132 ff., n. 169; MoroSini 1999, s. 88 f., n. 13; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, s. 124, n. 25; Succi 2011, s. 127 ff., n. 43). Somit dürfte das Gemälde in diesem oder dem vorhergehenden Jahr entstanden sein. Die erste Inventarisie-rung der Vedute geschah in einem heu-te verlorenen Inventar, doch lässt die Nummer auf eine Inventarisierung in den Jahren 1748/49 schließen (we-Ber 2004, s. 100, Anhang II). Falls Bellotto allerdings gehofft haben sollte, dass seine Veduten in der im Bild dar-

gestellten Gemäldegalerie ausgestellt werden sollten, so wurde er enttäuscht. Denn fast alle seiner Veduten wurden erst 1834 der Öffentlichkeit zugäng-lich gemacht, als sie in der sogenannten „Galerie vaterländischer Prospekte“ [Galerie der heimischen Ansichten] aufgehängt wurden (Zur Sammlungs-geschichte der Gemälde von Bellotto in Dresden: Henning 2011a, ss. 16 ff.). Dazu gehörte auch das hier ausgestell-te Werk. Gemeinsam mit den anderen Stadtansichten Bellottos wurde sie dann 1855 in die neue, nach Plänen von Gottfried Semper erbaute Gemäl-degalerie am Zwinger überführt, wo sie seitdem einen wichtigen Platz in der Dauerausstellung einnahm.Gemeinsam mit den anderen Werken, die Bellotto während seines ersten Auf-enthalts in Dresden schuf, markiert diese Vedute einen Höhepunkt im Schaffen dieses Künstlers. Sie darf nicht verwechselt werden mit einer fotografi-schen Aufnahme, die nur eins zu eins abbilden kann, was der Fotograf (oder Handybesitzer) vor der Linse sieht. Bellottos Vedute ist ein Kunstwerk, das mit künstlerischen Mitteln gestal-tet wurde. Dabei verband der Maler auf einmalige Weise die Präzision in den Details der Architektur mit einer lebensvollen Beschreibung des Alltags und einer nuancenreichen Lichtre-gie, so dass der Betrachter vor seinen großen Leinwänden wie selbstver-ständlich am Leben der vergangenen Epoche teilzunehmen vermag. Dank der grundlegenden Restaurierung, die 2016/18 in der Gemälde-Res-taurierungswerkstatt der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden durchge-führt wurde, ist die hohe Qualität der Malerei und ihre suggestive Wirkung jetzt wieder zu erleben. Mit der vorlie-genden Ausstellung kehrt diese Vedute erstmals wieder in die Öffentlichkeit zurück.

BibliographieKozaKiewicz 1972, 2, s. 132 ff., n. 167; waltHer 1995, s. 42 ff., fig. 10; Bernardo Bellotto 2001, s. 167 ff., n. 46; weBer 2004, s. 88, fig. 11; Wunschbilder 2009, s. 152 sgg., n. 3; Bernardo Bellotto 2011, s. 110, n. 177.

Dopo il restauro, particolareThe painting following the conservation treatment, detailDas Gemälde im Zustand nach der Restaurierung, Detail

-

Relazione di restauro

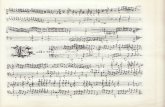

La veduta del Mercato nuovo dallo Jüdenhof, con la Gemäldegalerie sulla sinistra e la Frauenkirche in posizione centrale, si annovera tra i soggetti più noti appartenenti al ci-clo dei dipinti di Dresda di Bernar-do Bellotto. Dopo svariati decenni di esposizione ininterrotta presso la Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, il di-pinto necessitava di un esteso restau-ro; risultavano evidenti, in primo luogo, significativi sollevamenti e piccoli distacchi della pellicola pitto-rica (figg. 1-2). Inoltre, una vernice opaca e ingiallita comprometteva la percezione dei contrasti cromatici e di alcuni minimi e accurati par-ticolari della pittura. A un primo sguardo i precedenti ritocchi non risultavano quasi avvertibili, l’anali-si in fluorescenza ultravioletta aveva tuttavia evidenziato un reticolo di numerosi piccoli ritocchi nella parte raffigurante il cielo, lungo l’area inte-ressata dalla craquelure: ciò costituiva un indizio del fatto che la superficie, in quel settore del dipinto, dovesse aver subito pesanti abrasioni. Ulte-riori indagini avevano evidenziato l’instabilità dei bordi della tela e del-le foderature effettuate fino a quel momento, che rendevano necessari profondi interventi conservativi del supporto pittorico. L’esteso programma di restauro ha preso avvio con la rimozione della vernice (figg. 3-4). Sulla scorta dei test di solubilità è stato possibile scio-gliere progressivamente, dopo una breve fase di rigonfiamento, i diversi strati di vernice (in parte costituita anche da cera) con l’impiego di eta-nolo. L’utilizzo mirato dell’etanolo allo stato puro, senza l’aggiunta di un solvente apolare che avrebbe avu-to un effetto mitigante, e del conse-guente maggiore potere solvente ha avuto lo scopo di ridurre l’azione meccanica durante il procedimento di rimozione della vernice. L’impie-go di un agente gelificante – attraver-so il quale il rigonfiamento provoca-to dal solvente può essere limitato al livello della superficie, evitando cioè che il solvente stesso penetri a fondo nel dipinto – non è stato possibile

a causa dell’affiorare della craquelu-re e delle decoesioni della pellicola pittorica che facilmente l’avrebbero accompagnata. Dopo la rimozione della vernice le effettive condizioni della superficie sono diventate visibi-li. Oltre ai più recenti e relativamente piccoli distacchi della pellicola pitto-rica nella parte inferiore del dipinto, sono venute alla luce singole lacune stuccate di vecchia data, soprattut-to nella parte occupata dagli edifici architettonici e in primo piano. Al contrario, il cielo lungo la craquelure si è rivelato parzialmente, ma pesan-temente, abraso e sono emersi nu-merosi e piccolissimi distacchi della pellicola pittorica in corrispondenza delle intersezioni ad angolo delle li-nee di crettatura. La rimozione della vernice ha evidenziato colori con tonalità decisamente più fredde, un contrasto cromatico maggiore e una migliore definizione delle forme. Il ductus della pittura nonché le so-luzioni pittoriche più ingegnose, co-me le piccole incisioni praticate sulle stesure dei colori, sono risultate di nuovo chiaramente leggibili. Tuttavia l’effetto cromatico che il di-pinto ha oggi non corrisponde alle tonalità originarie volute da Bellot-to. Le tonalità di blu mostrano segni evidenti di invecchiamento della lu-minosità cromatica. Per il cielo Bel-lotto aveva utilizzato il blu di Prussia, un pigmento all’epoca relativamente nuovo; ma il blu di Prussia è poco fo-tostabile e l’intensità diminuisce con relativa rapidità, quindi nel corso del tempo l’area del dipinto occupata dal cielo si è notevolmente sbiadi-ta. Questo processo è documentato dalla presenza di tonalità di blu più accese sui bordi, le quali si sono con-servate perché sono rimaste coperte. Si tratta di alterazioni che perman-gono e non permettono restituzioni cromatiche. Una caratteristica importante che in-teressa l’intera superficie del dipinto è la craquelure: la pellicola ha risenti-to di tensioni in modo decisamente marcato e diffuso, e ciò dipende sia dalla tecnica pittorica sia dalla strut-tura dell’opera. Lungo i tracciati delle crettature, il film pittorico era solle-vato e in parte leggermente lacerato.

Queste aree erano particolarmente a rischio di decoesione o potevano anche verificarsi, nel peggiore dei casi, veri e propri distacchi, se la pel-licola pittorica fosse stata sottoposta a movimenti (dovuti a oscillazioni di temperatura o vibrazioni).Una fase importante del program-ma di restauro ha riguardato l’analisi di tutta la superficie del dipinto e il consolidamento delle aree a rischio di decoesione. Il consolidamento è stato effettuato con l’impiego di col-la di storione al 7% (7 g di colla per 100 ml di acqua) e in condizioni di calore e pressione moderati. Il conso-lidamento ottenibile era tuttavia cir-coscritto: la penetrazione della colla di storione era molto difficile, inol-tre questi interventi ci inducevano a rinunciare a causa di indurimenti della pellicola pittorica evoluti in microscopiche frantumazioni lungo i tracciati delle crettature, frantuma-zioni che rappresentano un ulteriore indebolimento dello strato pittorico e lo mettono a rischio. Un consoli-damento soddisfacente si è ottenuto solo nelle aree del dipinto in cui la colla è ben penetrata, e comunque anche qui soltanto entro un certo limite. La craquelure rimane, nono-stante l’intervento, molto marcata, parzialmente aperta e a rischio di futuri deterioramenti. Le lacune riscontrate sono localizza-te soprattutto in primo piano e nel-le parti del dipinto occupate dagli

edifici architettonici. Al contrario, il cielo è caratterizzato da abrasioni e numerosi minuscoli distacchi in corrispondenza delle intersezioni ad angolo delle linee di crettatura. Un antico segno di degrado, che si presenta sotto forma di una lacuna di grandi dimensioni, si riscontra sul lato superiore del dipinto ed è pre-sumibilmente riconducibile a una perforazione (fig. 5). Il restauro ha previsto l’eliminazione delle vecchie stuccature, ricostruite con una base a gesso e colla, quindi strutturate in conformità alla pelli-cola pittorica circostante. Il ritocco è stato eseguito perlopiù con tempere a gouache e intensificato nella misura in cui consistenza e aderenza al co-lore si avvicinavano all’originale (fig. 6). Il corposo intervento di ritocco effettuato con tempere a gouache è stato mirato a ottenere il migliore adeguamento cromatico possibile già prima dell’applicazione della ver-nice, in modo tale che, a conclusione di tutti gli interventi, i ritocchi e la vernice reagiscano all’invecchiamen-to in modo uniforme. La definitiva e ottimale armonizzazione croma-tica dei singoli ritocchi è avvenuta, riducendone al minimo l’impiego, mediante prodotti Gamblin (Con-servation Colors) sulla vernice. Il supporto pittorico originale è og-gi stabilizzato con una foderatura in colla di pasta del XIX secolo; alla stessa datazione risale anche la sosti-

1. Prima del restauro, particolare dello stato di conservazione, particolare1. The painting prior to the conservation treatment, detail1. Das Gemälde im Zustand nach der Restaurierung, Detail

-

tuzione del telaio originale con uno estensibile un po’ più grande, tanto che le estremità originali della tela occupano parzialmente la superficie del dipinto. La trama della stoffa del-la foderatura è molto sottile e oggi, a causa dell’invecchiamento, instabile. Una foderatura degli anni Ottanta avrebbe dovuto contribuire a una stabilizzazione, ma non includendo le estremità della tela, aveva generato numerosi strappi lungo le stesse. È stato quindi necessario rifare la fode-ratura per garantire in maniera dure-vole un alleggerimento della trazione esercitata sulle estremità. Un inter-vento, questo, che ha comportato il completo smontaggio del dipinto dal telaio, l’estrazione della cera in-trodotta nei bordi in occasione di un precedente tentativo di stabilizzazio-ne, la preparazione della foderatura dei bordi stessi e la sua applicazione. Per applicare le strisce di tela, tenen-do conto della quantità di cera nelle fibre, è stata ampiamente impiegata la pellicola adesiva BEVA 371. Per l’intervento finale, cioè quello re-

lativo all’applicazione della vernice, è stata utilizzata resina damar sciolta nella trementina (1 parte di damar per 3 parti di trementina). L’inter-vento, effettuato con leggere frizioni e per mezzo di tamponi, ha permesso di stendere uno strato molto sottile di vernice – in grado di conferire alla pittura una sufficiente qualità (in termini di contrasto e di lucen-tezza) – e fa sì che il retro del dipinto sia protetto dalla penetrazione della vernice (attraverso le aperture delle crettature), che viene così ridotta. L’applicazione di uno strato sottile di nuova vernice e l’utilizzo esclusivo di una resina fresca permettono di ral-lentare l’invecchiamento della resina naturale e quindi, in prospettiva, di evitare un consistente ingiallimento. La montatura della cornice era stata oggetto di interventi e ritocchi già in passato; lo stato della cornice si era conservato ed erano stati eseguiti circoscritti interventi di riparazione, infine era stata anche sottoposta a una vetrificazione protettiva.Le fotografie che documentano le

condizioni del dipinto prima e do-po il restauro evidenziano differenze chiaramente percepibili su tutta la superficie del dipinto stesso, sia a li-vello di cromaticità che di contrasto. Solo con la rimozione della vernice la chiarezza e il virtuosismo della pit-tura hanno potuto ritornare a essere inequivocabilmente visibili. Il bian-co della nuvola a destra accanto alla Frauenkirche era, prima del restau-ro, a malapena riconoscibile a causa dell’alterazione del valore cromatico provocata dall’invecchiamento della vernice. Tuttavia, anche al termine dei profondi interventi di restauro, le condizioni generali del dipinto ri-mangono delicate. La craquelure ca-ratteristica di questo dipinto richiede un’accurata e costante sorveglianza. Anche per il futuro, è assolutamente necessario che l’opera non sia sotto-posta a forti e prolungate vibrazioni e a oscillazioni climatiche.

Restoration Report

The view of the New Market from the Jüdenhof, with the Gemäldegalerie on the left and the Frauenkirche at the cen-tre, is one of the most famous paintings among Bernardo Bellotto’s Dresden series. After many decades of uninter-rupted display at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, the painting was in need of an extensive conservation treatment (fig. 1-2). To start with, the work pre-sented significant lifting and limited delamination of the paint layer. Fur-thermore, the opaque yellowed varnish impaired a correct appreciation of the chromatic contrasts and of some min-ute details of the painting. On a first examination, previous retouching was almost unnoticeable. However, ultra-violet examination detected a network of small inpaints in the sky area affect-ed by craquelure: this indicated that the surface in that sector had suffered substantial abrasion. Further tests re-vealed instability along the edges of the original canvas and on the perimeter of the relining canvas, a condition that required a comprehensive treatment on the painting support. The extensive conservation treatment started with the removal of the var-nish (fig. 3-4). Solubility tests were carried out and, after a brief swell-ing phase, the various layers of var-nish (which included a percentage of wax) could be progressively dissolved with the use of ethanol. The targeted use of pure ethanol, without the addi-tion of a non-polar solvent that would have mitigated its solvent action, was aimed at reducing the mechanical ac-tion on the surface during the actual varnish-removal process. The use of a gel-agent to restrict the solvent’s swell-ing effect only to the surface (to avoid the solvent reaching the ground layer) was not possible due to the craquelure and to the loss of cohesion of the paint layer that might have followed. After the varnish was removed, the actual conditions of the surface were visible. Besides the more recent and relatively limited delamination of the painting surface in the lower part of the picture, old stucco-filled lacunae appeared, especially in the areas with the build-ings and in the foreground. On the

2. Particolare del cavallo davanti alla carrozza del re; le aree, che presentano ora parziali minuscoli distacchi, erano fortemente danneggiate prima del restauro2. Detail of the horse in front of the king’s carriage. The areas now affected by partial and very limited delamination were severely damaged before the conservation treatment2. Detail des Pferdes vor der Kutsche des Königs; diese partiellen kleinteiligen Ausbrüche waren akute Schäden vor der Restaurierung

-

contrary, the sky in the area affected by craquelure appeared to be partially yet heavily abraded with several very small delaminations of the pictorial layer at the vertices, or the intersections between cracks. The varnish removal unveiled the colours’ distinctively cold-er tones as well as the painting’s greater chromatic contrast and sharper shape definition. The ductus of the painter’s brushwork as well as his most remark-able pictorial solutions, namely the slight “incisions” in the colour surface, also became clearly visible. The paint-ing’s present chromatic effect however does not correspond to Bellotto’s origi-nal intentions. The chromatic lumi-nosity of the shades of blue has clearly aged. For the sky Bellotto used Prussian blue, a pigment that was relatively new at the time but that has limited light stability, which caused its rather rapid loss of intensity and the visible fading of the sky area. This process is confirmed

by the brighter blue on the edges of the painting that have remained covered. These alterations are permanent and cannot be ameliorated. Craquelure is considerable across the entire painting surface: the paint layer has suffered marked and widespread tensions, due to the painting technique and to the artwork’s structure. Along the cracks, the pictorial surface has lifted and slightly lacerated. The con-ditions of these areas were particularly critical and could have led to loss of cohesion or even actual delamination, should the paint layer have been sub-jected to movement (due to tempera-ture variations or vibrations.)An important phase of the conservation programme consisted in the analysis of the entire surface of the painting and in the consolidation of the areas that could be affected by a loss of cohesion. To this effect sturgeon glue in a 7g per 100ml ratio was applied, in moderate

heat and pressure conditions. However, the level of consolidation that could be achieved was limited: the penetration of the sturgeon glue proved difficult. Furthermore, this operation caused the hardening of the paint layer leading to microscopic losses along the cracks that further weakened and endangered the colour layer. A satisfying level of con-solidation was obtained only in those areas where the glue could penetrate well and even in these areas only to a certain range. Despite the treatment, the craquelure remains very marked and partially open, and is at risk of worsening in the future. The lacunae are mainly in the fore-ground and in the area with buildings. On the contrary, the sky is marked by abrasions and numerous very small delaminations at the vertices (inter-sections between cracks). A lacuna of considerable size – an old sign of decay probably caused by a perforation – was

found in the upper side of the painting (fig. 5). The old stucco was removed and replaced with a plaster and glue base to match the surrounding picto-rial layer. Inpainting was carried out mainly with gouache and intensified whenever necessary in order to resem-ble the original texture and colour. The substantial gouache inpaints were aimed at obtaining the best possible adjustment of the chromatic composi-tion, even before applying the varnish, so that inpaints and varnish will age uniformly (fig. 6). The final chromatic adjustments to reach the best possi-ble harmonising of the inpaints were carried out with a minimum use of Gamblin (Conservation Colors) on the varnish. A nineteenth-century starch-paste lining currently stabilises the original canvas; to that same period dates the replacement of the original strainer with a slightly larger stretcher, which

3. Durante il restauro, rimozione della vernice3. The painting during the removal of the varnish3. Gesamtaufnahme des Gemäldes während der Firnisabnahme

-

explains why the original extremities of the canvas partially occupy the sur-face of the painting. Due to its very fine weave and to ageing, the lining has become unstable. Furthermore, in

the 1980s, the painting was lined to increase its stability, but this operation was the cause of the many tears along its perimeter since the lining did not cover the entire canvas. For this reason,

it was necessary to reline the painting to assure a long-lasting reduction of trac-tion at the extremities. This operation required the complete removal of the painting from its strainer, the removal

of the wax that had been inserted along the borders during a previous attempt to stabilise the work, the preparation of the lining for the edges, and its ap-plication. To apply the strips of canvas, considering the quantity of wax inside the fibres, the BEVA 371 adhesive film was used extensively. The final stage of the conservation treatment – varnish application – was carried out with a damar resin in turpentine (1 part damar 3 parts turpentine). The operation, performed with light frictions using cotton swabs, allowed the application of a very fine layer of varnish providing sufficient quality to the painting (in terms of con-trast and brightness) while also protect-ing the rear of the painting by reducing the penetration of the varnish into the craquelure. The application of such a fine layer of new varnish and the use of only fresh resins will reduce the ageing of the natural resin and therefore avoid substantial yellowing in the future. The structure of the frame showed vis-ible signs of previous treatments and retouching. The frame itself had pre-served and had been subjected to lim-ited repairs and to a protective glazing.The photographs documenting the con-ditions of the painting before and after the conservation treatment highlight noticeable differences across the paint-ing’s entire surface, both in terms of chromatic quality and contrast. Only with the removal of the varnish could the clear and virtuoso painting tech-nique be visible once again. Before the treatment, due to the alteration of the chromatic levels and to the ageing of the varnish, the white of the cloud on the right, next to the Frauenkirche, was barely recognisable. Notwithstanding the radical conservation treatment it underwent, the painting’s general conditions remain delicate. The cra-quelure that characterises this painting must be constantly monitored. It is ab-solutely necessary that the painting does not undergo any strong or prolonged vibrations and climatic oscillations.